Experiencing Antiquity in the Postwar Hollywood Epic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nightlife, Djing, and the Rise of Digital DJ Technologies a Dissertatio

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Turning the Tables: Nightlife, DJing, and the Rise of Digital DJ Technologies A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Kate R. Levitt Committee in Charge: Professor Chandra Mukerji, Chair Professor Fernando Dominguez Rubio Professor Kelly Gates Professor Christo Sims Professor Timothy D. Taylor Professor K. Wayne Yang 2016 Copyright Kate R. Levitt, 2016 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Kate R. Levitt is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION For my family iv TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE……………………………………………………………….........iii DEDICATION……………………………………………………………………….......iv TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………...v LIST OF IMAGES………………………………………………………………….......vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………….viii VITA……………………………………………………………………………………...xii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION……………………………………………...xiii Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..1 Methodologies………………………………………………………………….11 On Music, Technology, Culture………………………………………….......17 Overview of Dissertation………………………………………………….......24 Chapter One: The Freaks -

UNITED SPIRITS Alcohol Beverage Industry India

UNITED SPIRITS Alcohol beverage industry India INDIAN ALCHOLBEV INDUSTRY IndianIndian Made IndianIndian Made BeerBeer Wine ForeignForeign LiquorLiquor IndianIndian Liquor (IMFL) (IMIL) IMFL category accounts for almost 72% of the market. Alcohol industry growth rate Spirits Market in India by Volume 5% 5% 5% 4% 4% 4% 3% 4% 4% 4% 15% 15% 15% 14% 14% 14% 13% 20% 19% 17% 22% 22% 21% 21% 19% 16% 17% 18% 22% 22% 59% 59% 60% 59% 59% 60% 60% 61% 61% 64% 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Whisky Brandy Rum White Spirits Spirit Market in India by Value 5% 5% 4% 4% 6% 6% 5% 6% 6% 6% 14% 14% 13% 12% 10% 10% 10% 10% 10% 9% 11% 10% 11% 12% 12% 12% 12% 12% 12% 11% 70% 69% 71% 72% 72% 73% 73% 73% 74% 75% 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Whisky Brandy Rum White Spirits Source: Equrius Report Major players in the industry Major Companies in the Indian Liquor Market Source: Equrius Report Top liquor brands in India Source: Equrius Report United Spirits – Diageo India World’s second largest liquor company by Volume. Subsidiary of Diageo PLC. One of the leading players of IMFL in India with a strong bouquet of brands like Mcdowell’s, Signature, Royal Challenge etc. In 2013, Diageo PLC acquired 10% stake in the company and gradually ramped up its share to 55% by the end of 2014. The main inflexion point came in 2015, after the whole company came under the control of Diageo PLC. -

PLACES of ENTERTAINMENT in EDINBURGH Part 5

PLACES OF ENTERTAINMENT IN EDINBURGH Part 5 MORNINGSIDE, CRAIGLOCKHART, GORGIE AND DALRY, CORSTORPHINE AND MURRAYFIELD, PILTON, STOCKBRIDGE AND CANONMILLS, ABBEYHILL AND PIERSHILL, DUDDINGSTON, CRAIGMILLAR. ARE CIRCUSES ON THE WAY OUT? Compiled from Edinburgh Theatres, Cinemas and Circuses 1820 – 1963 by George Baird 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS MORNINGSIDE 7 Cinemas: Springvalley Cinema, 12 Springvalley Gardens, 1931; the seven cinemas on the 12 Springvalley Gardens site, 1912 – 1931; The Dominion, Newbattle Terrace, 1938. Theatre: The Church Hill Theatre; decision taken by Edinburgh Town Council in 1963 to convert the former Morningside High Church to a 440 seat theatre. CRAIGLOCKHART 11 Skating and Curling: Craiglockhart Safety Ponds, 1881 and 1935. GORGIE AND DALRY 12 Cinemas: Gorgie Entertainments, Tynecastle Parish Church, 1905; Haymarket Picture House, 90 Dalry Road, 1912 – became Scotia, 1949; Tivoli Picture House, 52 Gorgie Road, 1913 – became New Tivoli Cinema, 1934; Lyceum Cinema, Slateford Road, 1926; Poole’s Roxy, Gorgie Road, 1937. Circus: ‘Buffalo Bill’, Col. Wm. Frederick Cody, Gorgie Road, near Gorgie Station, 1904. Ice Rink: Edinburgh Ice Rink, 53 Haymarket Terrace, 1912. MURRAYFIELD AND CORSTORPHINE 27 Cinema: Astoria, Manse Road, 1930. Circuses: Bertram Mills’, Murrayfield, 1932 and 1938. Roller Skating Rink: American Roller Skating Rink, 1908. Ice Rink: Murrayfield Ice Rink; scheme sanctioned 1938; due to open in September 1939 but building was requisitioned by the Government from 1939 to 1951; opened in 1952. PILTON 39 Cinema: Embassy, Boswall Parkway, Pilton, 1937 3 STOCKBRIDGE AND CANONMILLS 40 St. Stephen Street Site: Anderson’s Ice Rink, opened about 1895;Tivoli Theatre opened on 11th November 1901;The Grand Theatre opened on 10th December 1904;Building used as a Riding Academy prior to the opening of the Grand Picture House on 31st December 1920;The Grand Cinema closed in 1960. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

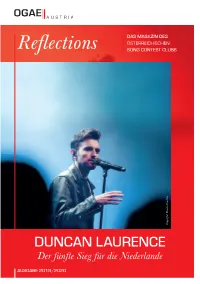

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

TPTV Schedule December 14Th to December 20Th 2020

th th TPTV Schedule December 14 to December 20 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 14 01:40 Piccadilly Third Stop 1960. Drama. Directed by Wolf Rilla. Starring Terence Morgan, Yoko Tani & John Crawford. Dec 20 Morgan as a playboy petty thief looking for the big time & Crawford as a yank in London and bad tempered crook. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE ) Mon 14 03:25 The David Niven The Lady from Winnetka. Jacques Bergerac, Argentina Brunetti & Eduardo Ciannelli. British Dec 20 Show actor David Niven, introduces this 1950s US anthology series. (S1, E7) Mon 14 03:55 Who Were You With Glimpses. 1963. 'Who Were You With Last Night' with the Paramount Jazz Quartet. Dec 20 Last Night - Glimpses Mon 14 04:00 Hannay Death with Due Notice. 1988. Stars Robert Powell, Christopher Scoular & Gavin Richards. A Dec 20 quiet break in the country turns into a weekend of murder when Hannay is targeted by a killer. (S1, E04) Mon 14 05:00 Amos Burke: Secret Whatever Happened To Adriana, and Why Won't She Stay Dead. Burke must remove the Dec 20 Agent blackmail threat from a Sicillian official and stop the shipment of missiles. Mon 14 06:00 Christmas Is a Legal 1962 Drama. Directed by Robert Ellis Miller. Mr Jones (James Whitmore), a lawyer who Dec 20 Holiday pursues the case of the underdog with determination and his own style. Barbara Bain, Don Beddoe & Hope Cameron. Mon 14 06:30 All For Mary 1955. Comedy. Director: Wendy Toye. Stars Nigel Patrick, Kathleen Harrison & David Dec 20 Tomlinson. In an Alpine resort, an officer & upper-class Humpy Miller set their sights on the landlord's daughter. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

The Queen of Sheba Visits Solomon

General Church Paper f the Seventh-day Adventists JUNE 29, 1978 The queen of Sheba visits Solomon See article op, page 10 THIS WEEK Re mew Contents Veronica Morrish of Greenbelt, membership (see also "SAD General Articles Pages 3-12 Maryland, learned to build a new Passes 400,000 Membership Columns attitude for herself. In "The Mark," p. 19). For the Younger Set 9 Garment of Praise" (p. 4), Mrs. The index of articles, authors, %IF For this Generation 14 Morrish, who teaches preschool and subjects that we publish 128th Year of Continuous Publication children in her home, describes twice yearly begins on page 27. Focus on Education 15 EDITOR Family Living 13 how she recovered faith in God This index has proved to be a Kenneth H. Wood From the Editors 15 and expelled her hatred for those valuable aid to many researchers. ASSOCIATE EDITORS Newsfront 17-26 who so maliciously wronged her. Art and photo credits: J. J. Blanco, Don F. Neufeld News Notes On page 6 the REVIEW editor Cover, Herbert Rudeen; p. 3, ASSISTANT EDITOR 25 Jocelyn Fay Index 27-31 continues his report on the trip he Gene Ahrens; p. 4, Tom Dun- and his wife, Miriam Wood, bebin; p. 9, Harold Munson; p. ASSISTANT TO THE EDITOR Back Page 32 Eugene F. Durand made recently to South America, 10, Gert Busch; p. 11, NASA; ADMINISTRATIVE SECRETARY In her darkness and despair a division that has just surpassed all other photos, courtesy of the Corinne Russ following her husband's murder, the 400,000 mark in church respective authors. -

The Evolution of Hollywood's Representation of Arabs Before 9/11: the Relationship Between Political Events and the Notion of 'O

Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol 1, No 2 (2007) ARTICLE The evolution of Hollywood's representation of Arabs before 9/11: the relationship between political events and the notion of 'Otherness' SULAIMAN ARTI, Loughborough University ABSTRACT This article will deliberate on the political motives behind the stereotypical image of Arabs in Hollywood in the period before 9/11. Hollywood has always played a propagandist as well as a limitative role for the American imperial project, especially, in the Middle East. This study suggests that the evolution of this representation has been profoundly influenced by political events such as the creation of Israel, the Iranian Islamic revolution and the demise of the Soviet Union. Hollywood’s presentation of Arabs through a distinctive lens allows America, through Hollywood, to present the Middle East as ‘alien’ and so helps to make it an acceptable area for the exercise of American power. The interpretations of Hollywood’s representation of Middle Easterners involve different, often contradictory, types of image. They also suggest that the intensification of the Arabs’ stereotypical image over the last century from ‘comic villains’ to ‘foreign devils’ did not occur in a vacuum but, certainly, with the intertwinement of both political and cultural interests in the region. It is believed that this was motivated indirectly by U.S imperial objectives. KEYWORDS Imperialism, Propaganda, Hollywood, Arabs, Politics and Others. Introduction The Middle East has long been ubiquitous in American cultural rhetoric; topics featuring Arabs and Muslims appear in various American media including discussions, news coverage and, most accessibly and influentially, in films and television entertainment programmes. -

Iuru!It Nrws Issued by the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust to Members of the Trust

iUru!it Nrws Issued by The Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust to Members of the Trust. Winter Edition, 1967 Price 10c. LINE-UP? ERDI'S "Don Carlos" and V Wagner's "Tannhauser" are among the operas being discussed for presentation at the 1968 Ade laide Festival of Arts along with the "Tosca" which, as already announced, will feature two of Europe's supreme dramatic singers, soprano Marie Collier and baritone Tito Gobbi. F "Don Carlos" and 'Tann I hauser" are, in fact, brought into the Elizabethan Trust Opera Com pany's repertoire for the Festival, they will subsequently be toured through other capitals as part of the company's main tour for 1968. The main tour is expected to fol Tita Gobbi Marie Collier as Tosca low on immediately from the Ade as Scarpia laide season. without a peer in his own generation, will ennially timely taunts at officialdom, Finn and final announcement cannot be making his first visit to Australia at "The Inspector-General", and a new play yet be made regarding the company's full Festival time. commissioned from Australian writer operatic bill for 1968, but it is known The electrifying excitement which Patricia Hooker will also feature in the that operas such as Puccini's "Girl of the 1968 Festival's drama activity. Golden West" and Menotti's "The Saint these two singers are able to generate of Bleecker Street" are receiving ardent in an audience at every performance is A LTHOUH a tour of Asia during 1968 advocacy in influential quarters. expected to make their joint appearance will preclude appearances by the The last operatic appearances in Aus in "Tosca" at Adelaide "a milestone in Australian Ballet at Adelaide Festival tralia of Victoria-born Marie Collier, the history of operd in Australia", as time, executives of the Festival are con now acclaimed throughout the world as a the Trust's Executive Director, Stefan tinuing negotiations for the presentation dramatic singer of resource not excelled Haag described it in announcing the of another notable ballet company. -

Flesh Wounds

Flesh Wounds Flesh Wounds The Culture of Cosmetic Surgery Virginia L. Blum UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2003 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blum, Virginia L., 1956–. Flesh wounds: the culture of cosmetic surgery / Virginia L. Blum. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-90158-4 1. Surgery, Plastic—Social aspects. 2. Surgery, Plastic—Psychological aspects. I. Title. rd119 .b58 2003 617.9Ј5—dc21 2002154915 Manufactured in the United States of America 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 987654 321 The paper used in this publication is both acid-free and totally chlorine-free (TCF). It meets the minimum requirements of ANSI /NISO Z39.48–1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). To my father, David Blum and to my mother, Fern Walder CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix 1. The Patient’s Body 1 2. Untouchable Bodies 35 3. The Plastic Surgeon and the Patient: A Slow Dance 67 4. Frankenstein Gets a Face-Lift 103 5. As If Beauty 145 6. The Monster and the Movie Star 188 7. Being and Having: Celebrity Culture and the Wages of Love 220 viii / Contents 8. Addicted to Surgery 262 Notes 291 Works Cited 315 Index 341 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people have contributed to this project, from reading chapters to helping me think through a range of ideas and possibilities, from pro- viding close editorial scrutiny to sharing enlightening telephone con- versations. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films,