Understanding How to Improve Team Collaboration Within Intensive Care Unit Transitional Care from the Perspective of Quality Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organizational Culture and Knowledge Management Success at Project and Organizational Levels in Contracting Firms

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PolyU Institutional Repository This is the Pre-Published Version. Organizational Culture and Knowledge Management Success at Project and Organizational Levels in Contracting Firms Patrick S.W. Fong1 and Cecilia W.C. Kwok2 ABSTRACT This research focuses on contracting firms within the construction sector. It characterizes and evaluates the composition of organizational culture using four culture types (Clan, Adhocracy, Market, and Hierarchy), the strategic approach for knowledge flow, and the success of KM systems at different hierarchical levels of contracting organizations (project and parent organization level). Responses from managers of local or overseas contracting firms operating in Hong Kong were collected using a carefully constructed questionnaire survey that was distributed through electronic mail. The organizational value is analyzed in terms of the four cultural models. Clan culture is found to be the most popular at both project and organization levels, which means that the culture of contracting firms very much depends on honest communication, respect for people, trust, and cohesive relationships. On the other hand, Hierarchy 1 Associate Professor, Department of Building & Real Estate, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong (corresponding author). T: +(852) 2766 5801 F: +(852) 2764 5131 E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Building & Real Estate, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong. 1 culture, which focuses on stability and continuity, and analysis and control, seems to be the least favored at both levels. Another significant finding was that the two main KM strategies for knowledge flow, Codification and Personalization, were employed at both project and organization levels in equal proportion. -

Project Management © Adrienne Watt

Project Management © Adrienne Watt This work is licensed under a Creative Commons-ShareAlike 4.0 International License Original source: The Saylor Foundation http://open.bccampus.ca/find-open-textbooks/?uuid=8678fbae-6724-454c-a796-3c666 7d826be&contributor=&keyword=&subject= Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 Preface ............................................................................................................................2 About the Book ..............................................................................................................3 Chapter 1 Project Management: Past and Present ....................................................5 1.1 Careers Using Project Management Skills ......................................................................5 1.2 Business Owners ...............................................................................................................5 Example: Restaurant Owner/Manager ..........................................................................6 1.2.1 Outsourcing Services ..............................................................................................7 Example: Construction Managers ..........................................................................8 1.3 Creative Services ................................................................................................................9 Example: Graphic Artists ...............................................................................................10 -

Designing, Developing and Implementing a Management System: an Overview (April 2010)

Designing, Developing and Implementing a Management System: An Overview (April 2010) Host: Emily Smorol, Corporate Environmental Affairs Speakers: Patrick Aurrichio, Program Manager, Corporate Environmental Affairs Emily: Welcome to our IBM Podcast titled, “Designing, Developing, and Implementing a Management System: An Overview.” My name is Emily Smorol and I work in IBM’s Corporate Environmental Affairs and Product Safety organization. There is an accompanying presentation available to download for this Podcast. For those following along with the presentation slides, please go to slide 2. The purpose of this Podcast is to discuss what a management system is and to provide an overview of its basic components. This Podcast is not meant to be all-inclusive but rather provide an approach to designing, developing, and implementing a management system in a sustained manner that has been successful for us – and which also may prove to be helpful to others setting out to do similarly. Today, we are going to be speaking with IBM’s Corporate Environmental Affairs Program Manager, Patrick Aurrichio. Patrick was instrumental in developing and implementing IBM’s global Environmental Management System. Recognizing that our audience comes from a diverse background – those with experience or familiarity with management systems and those for whom this may be a new concept – Patrick, how would you describe what a management system is? Patrick: Thank you Emily – and welcome to those joining the podcast. If you’re following along with the slide presentation, please turn to slide 3. First I’d like to mention and want you to understand that there is nothing overwhelmingly special or difficult with designing or developing a management system. -

Project Information Management PROJECT MANAGEMENT for DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS Project Information Management

pm4dev, 2016 –management for development series © Project Information Management PROJECT MANAGEMENT FOR DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS Project Information Management PROJECT MANAGEMENT FOR DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS A methodology to manage development projects for international humanitarian assistance and relief organizations © PM4DEV 2016 Our eBook is provided free of charge on the condition that it is not copied, modified, published, sold, re-branded, hired out or otherwise distributed for commercial purposes. Please give appropriate citation credit to the authors and to PM4DEV. Feel free to distribute this eBook to any one you like, including peers, managers, and organizations to assist in their project management activities. www.pm4dev.com Project Information Management INTRODUCTION “If you fail to plan, you plan to fail.” “.. A major weakness is the ability of project staff to utilize their logframe for designing a coherent and integrated, overall information system, where a manageable and limited number of feasible information activities are planned, which together will ensure that effective effect and impact level monitoring will occur. It is typical for projects to end up collecting too much rather than too little information. Frequently though, much of this information is not relevant to monitoring the results and impacts for which the project is accountable, and that which is, is not collected sufficiently reliably or regularly. By restricting the number, but improving the quality and reliability of their major information gathering activities, projects will much improve their information systems.” CARE International EDIAIS Case Study Project Information Management Plan Detailed planning is critical to the development of usable, high quality information deliverables that meet the needs of internal and external information users. -

LFS – Logistics Focused Solutions Integrated Total Solutions

LFS – Logistics Focused Solutions Integrated total solutions EPS – Ehrhardt + Partner Solutions DWC-LLC | Software Systems for Warehouse Logistics P.O.Box 644 300 | Dubai, UAE | Phone (+971) 4-870 1000 | Fax (+971) 4-870 1050 [email protected] | www.ehrhardt-partner.ae Warehouse-Management by E+P The internationally leading expert for warehouse logistics Ehrhardt + Partner GmbH & Co. KG | Software Systems for Warehouse Logistics Alte Römerstraße 3 | D-56154 Boppard-Buchholz | Germany | Phone (+49) 67 42-87 27 0 | Fax (+49) 67 42-87 27 50 [email protected] | www.ehrhardt-partner.com Contents LFS – Logistics Focused Solutions ................................................................................... 3 A system for all requirements The warehouse management system for all platforms Open system solution for your IT architecture LFS as a central solution for your warehouse logistics .................................................... 6 The total solution for your individual task definitions Central software installation for different countries and warehouses LFS as a hosting and cloud solution Setting standards with innovations ................................................................................... 8 Pick-by-Voice Voice service and support RFID Multi-order picking LFS – a system solution all types of work ...................................................................... 10 Professional connection of automatic warehouse units Systematic warehouse modernisation Sound advice and scheduled implementation -

LNCS 8407, Pp

Knowledge Management: Organization Culture in Healthcare Indonesia Dana Indra Sensuse1, Yudho Giri Sucahyo1, Siti Rohajawati2, Haya Rizqi1, and Pinkie Anggia1 1 Computer Science Faculty, University of Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia {dana,yudho}@cs.ui.ac.id, {pinkie.anggia.id,cold.ryz}@gmail.com 2 Dept. of Information System, Bakrie University, Jakarta, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract. Nowadays organizations realize that knowledge is an important asset to achieve a competitive advantage. In the favor of that, it is necessary for or- ganizations to manage and utilize the knowledge as much as possible through knowledge management (KM). KM concept is not only used in large compa- nies, but also has begun to be adopted by healthcare organization in an effort to improve the quality of services. Managing knowledge is not easy, a lot of factors to consider, one of which is the culture of the organization. Organiza- tional culture is defined as a set of practices, values, and assumptions held by members of the organization and are able to influence the behavior of the organization [12, 13]. According to Kim Cameron and Robert Quinn (2006), organizational culture can be examined using ‘Organizational Culture Assess- ment Instrument’ (OCAI) which has a framework, called the competing value framework (CVF). This framework consists of four culture types i.e. clan, adhocracy, market, and hierarchy. In this research, we found that healthcare organization in Indonesia have developed a dominant culture-style. It is a mix of the market and hierarchy. In addition, we also discuss the relationship of four culture types with KM, and six dimensions of organizational culture. -

The Intelligent Management System: an Overview

The Intelligent Management System: An Overview Mark S. Fox The Robotics Institute Carnegie-melt on University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 . 7 becember 1982 Abstract: This paper describes the Intelligent Management System (IMS) project, which is part of the Factory of the Future project in the Robotics Institute of Carnegie-Mellon University. IMS is a long term project concerned with applying artificial intelligence techniques in aiding professionals and managers in their day to day tasks. This report discusses both the long term goals of IMS, and current research. It describes research in the modeling of organizations, constraint- based job-shop scheduling, organization simulation, user interfaces, and system architecture. Examples of working systems are provided. Copyright @ 1982 Intelligent Systems Lab., CMU Robotics Inst. This research was supported by the Robotics Institute, Carnegie-Mellon University, and, in part, by the Westinghouse Corporation. To appear in: "Processes and Tools For Decision Support", [H.Sol- Editor] Netherlands: North-HollandCompany, 1982. Revised Version. -. .. .- .. Intelligent Management System Table of Contents 1 1. Introduction 2. Functional Goals 2 3. Architectural Goals 5 7 c 4. Organization Modelling 4.1. Introduction 7 4.2. Basic Modetling System 10 4.3. Model Accessibility and Extensibility 14 4.4. Flow-Shop Modelling 17 4.5. Job-Shop Modelling 19 4.6. Machine Modelling 20 5. Organization Analysis 20 5.1. Introduction 20 5.2. Simulation 21 5.3. Structure Analysis 23 6. Organization Operation and Management 24 6.1. Introduction 24 6.2. Job-Shop Scheduling 24 6.3. Factory Monitoring 28 6.4. Process Diagnosis 28 7. User Interfaces 28 7.1. -

Quality Assurance Management System Guide for Use with .

Preamble to DOE G 414.1-2A, Quality Assurance Management System Guide, dated 6-17-05 Quality Assurance (QA) Management System Guide Enhancements DOE elements and DOE contractors should consult this Guide to develop and implement effective management systems that are consistent with the Department’s quality expectations of the QA Rule, 10 CFR 830 Subpart A, and DOE O 414.1C, Quality Assurance, dated 6-17-05, and that support the Safety Management System Policy, DOE P 450.4, dated 10-15-96. The revised QA management system guide includes enhancements arising from experience with implementing the DOE QA Rule and DOE O 414.1C. The Guide was evaluated in light of key policy initiatives, Directive changes, and other changes that have occurred within DOE since the Guide was last issued. Evaluation and coordination with user groups have identified specific major improvements to the guide as follows. • Clarified the scope of the guidance to include the QA Order, DOE O 414.1, and the QA Rule, 10 CFR 830 Subpart A. • Incorporated review guidance for use by DOE in evaluating site office or contractor quality management systems for approval (it may also be tailored for use by contractors to review subcontractor QAPs). • Incorporated a new QA Assessment Template for use in conducting assessments of QA Program implementation. • Incorporated hyperlinks to the expanded guidance. • Discussed the use of third party management system validation. • Updated information pertaining to the identification and control of suspect/counterfeit items (S/CIs) and links to expanded guidance for S/CIs. • Expanded information on the grading process to include programmatic and mission-critical considerations and a description of the steps in implementing the grading process. -

Quality Management System (QMS) for Apis

Quality Management System (QMS) for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (API) Manufacturers integrating GMP (ICH Q7a) into ISO (9001: 2000) September 2005 APIC / CEFIC Quality Management System - integrating GMP (ICH Q7a) into ISO (9001: 2000) Page 2 of 73 Table of Contents I. Introduction II. Objective and Scope III. Quality Management Systems for API manufacturers 1. Quality Management System 2. Management responsibility 3. Resource management 4. Product realization (Manufacturing Operations) 5. Measurement, analysis and improvement (Evaluation Activities) IV. Supplementary Information 1. Identification of system approaches in Q7a 2. Description of processes 3. Structure of a Quality Manual 4. Cross-reference of APIC QMS documents (from “old” to “new”) 5. Assistance for implementation of a QMS 6. Matrix GMP(Q7a) / ISO (9001:2000) V. Glossary VI. Abbreviations VII. References VIII. Acknowledgements APIC / CEFIC Quality Management System - integrating GMP (ICH Q7a) into ISO (9001: 2000) Page 3 of 73 I. Introduction The changing regulatory environment In a Science Board Meeting held in November 2001, FDA raised some concerns regarding the efficiency of the pharmaceutical industry. The factors contributing to this situation were identified as follows: • Pharmaceuticals are complex, multivariate physicochemical systems that are - Often treated (during development) as univariate systems (one-factor-at-a-time, trial- and-error experimentation) - Physical properties of materials normally not well characterized - Equipment selection based on tradition - Process factors are not well understood • Development is done under time crunch • Post approval changes require regulatory oversight It was said that a higher efficiency is required in order to provide high quality drugs to the market in a timely manner, to successfully take advantage of the new drug development opportunities offered by advances in chemistry and biology. -

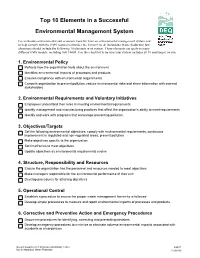

Top 10 Elements in an Environmental Management System

Top 10 Elements in a Successful Environmental Management System For maximum environmental and economic benefits from an environmental management system and to help comply with the EMS requirement under the Toxics Use & Hazardous Waste Reduction law, a business should include the following 10 elements in its system. These elements can apply to many different EMS models, including ISO 14001. Use this checklist to be sure your system includes all 10 and keep it on site. 1. Environmental Policy Reflects how the organization feels about the environment Identifies environmental impacts of processes and products Ensures compliance with environmental requirements Commits organization to prevent pollution, reduce environmental risks and share information with external stakeholders 2. Environmental Requirements and Voluntary Initiatives Employees understand their roles in meeting environmental requirements Identify management and manufacturing practices that affect the organization's ability to meet requirements Identify and work with programs that encourage preventing pollution 3. Objectives/Targets Set the following environmental objectives: comply with environmental requirements; continuous improvement in regulated and non-regulated areas; prevent pollution Make objectives specific to the organization Set timeframes to meet objectives Update objectives as environmental requirements evolve 4. Structure, Responsibility and Resources Ensure the organization has the personnel and resources needed to meet objectives Make managers responsible for -

Organizational Culture Types That Academicians Associate with Their Institutions

http://ijhe.sciedupress.com International Journal of Higher Education Vol. 7, No. 6; 2018 Organizational Culture Types that Academicians Associate with Their Institutions Semra Kıranlı Güngör1 & Hakan Şahin2 1 Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Faculty of Education, Educational Sciences, Turkey 2 Directorate of National Education, Eskişehir, Turkey Correspondence: Semra Kıranlı Güngör, Faculty of Education, Educational Sciences, Eskişehir Osmangazi Univesity, Eskişehir, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 24, 2018 Accepted: December 18, 2018 Online Published: December 20, 2018 doi:10.5430/ijhe.v7n6p161 URL: https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v7n6p161 This study is produced of the Hakan Şahin’s Eskisehir Osmangazi University Institute of Educational Sciences, Department of Higher Education Administration and Policy Master Thesis work that was carried out on May 29, 2018, defended and resulted in success with Consultancy of Assistant Prof. Dr. Semra KIRANLI GÜNGÖR. Abstract This study, considering the sample of a university located in central Anatolia region, Turkey, aims to identify culture types that the academicians perceive in relevant with their institutions according to the 4 types of cultures (Clan, Adhocracy, Hierarchy, and Market) given in the Competing Values Framework by Cameron and Quinn. The study includes 205 academicians from different faculties and vocational schools as participants. The data was obtained from the Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) that has been prepared particularly for the research group. Analyzes of the data obtained in the study were carried out with statistical package programs as IBM SPSS Statistics 23 and Interactive Lisrel SSI 8.72. The demographic features of the academicians were determined with percentage and frequency analyzes and the mean and standard deviation statistics were used in determining the perception levels of organizational culture types which academicians associate with their universities. -

Evidence That Sets the Record Straight – How Management System Standards Add Value to Any Organization Authors; Mark Ames

Evidence That Sets the Record Straight – How Management System Standards Add Value to Any Organization Authors; Mark Ames, President, AQS Management Systems, Inc. Reg Blake – VP Corporate Development and Regulatory Affairs, BSI Group America, Inc. Michael J. Caruso, Vice President – Certification, UL DQS Inc. Phil Heinle, Owner, Quality Consulting More than ever, businesses need ways to improve their operations to better gain, serve, and retain customers, while reducing costs and improving margins. Implementing management systems and attaining third-party accredited certification can help businesses achieve success on all of these fronts. For many years, various media have discussed anecdotal information concerning the value of third party accredited certification to management systems. Sound, documented evidence from academic studies now confirms the value of third- party accredited certification of management systems. The most noteworthy studies about management system standards in the last 20 years have dealt with the two most popular standards: ISO 9001 (Quality Management Systems) and ISO 14001 (Environmental Management Systems). In this article, we will focus not only on the value of these and other management systems, but also, in particular, on the value of Accredited Management Systems Certification. Most articles on this topic have been positive, while a few have been negative, but not many have been based on hard data. We've now reached the time to clearly communicate the data associated with the benefits of adopting management system standards. Here are a few basic conclusions of recent studies (additional benefits and the specific data that supports these conclusions will be presented later in this article): • Management systems standards return bottom-line financial value larger than any investment or time incurred.