The Jews of Omaha: the First Sixty Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

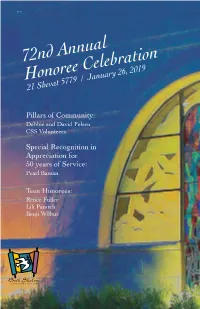

72Nd Annual Honoree Celebration 21 Shevat 5779 / January 26, 2019

B’’H 72nd Annual Honoree Celebration 21 Shevat 5779 / January 26, 2019 Pillars of Community: Debbie and David Felsen CSS Volunteers Special Recognition in Appreciation for 50 years of Service: Pearl Bassan Teen Honorees: Renee Fuller Lili Panitch Benji Wilbur Program Shabbat Morning Recognition of Teen Honorees Renee Fuller Lili Panitch Benji Wilbur Saturday Evening Opening Remarks Presentation of Honorees Pillars of the Community Debbie and David Felsen Community Security Service (CSS) Volunteers Recognition of 50 Years of Service Pearl Bassan Closing Remarks Pillars of Special Recognition Community Honorees for 50 Years of Service Debbie and David Felsen Pearl Bassan The Felsens became involved in the Beth Sholom community almost Pearl has been an essential part of Beth Sholom for more than 50 years. immediately upon coming to Potomac. Debbie is the quintessential She has worked with 6 rabbis, 4 executive directors, 2 cantors and in Jewish hostess, opening her home to friends and visitors. Debbie also 2 buildings. An essential component of the transition from 13th and provides support for various programs throughout the shul. David Eastern to Potomac, she takes pride in how she actually became friends served on the Board of Directors and served three terms as President. with many of our members and still keeps in touch with them. Pearl During David’s tenure, Beth Sholom made significant changes, started her Jewish communal career with her husband, Jake, when including the hiring of Rabbanit Fruchter and Executive Director they directed the Hillel at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario. Jessica Pelt, and the initiation of CSS. The Felsens are involved in She brought that same dedication to the entire Washington Jewish learning, fundraising and hospitality throughout the shul and the greater community. -

Transcontinental Railroad Fact Sheet

Transcontinental Railroad Fact Sheet Prior to the opening of the transcontinental railroad, it took four to six months to travel 2000 miles from the Missouri River to California by wagon. January 1863 – Central Pacific Railroad breaks ground on its portion of the railroad at Sacramento, California; the first rail is laid in October 1863. December 1863 – Union Pacific Railroad breaks ground on its portion of the railroad in Omaha, Nebraska; due to the Civil War, the first rail is not laid until July 1865. April 1868 – the Union Pacific reaches its highest altitude 8,242 feet above sea level at Sherman Pass, Wyoming. April 28, 1869 – a record of 10 miles of track were laid in a single day by the Central Pacific crews. May 10, 1869 – the last rail is laid in the Golden Spike Ceremony at Promontory Point, Utah. Total miles of track laid 1,776: 690 miles by the Central Pacific and 1086 by the Union Pacific. The Central Pacific Railroad blasted a total of 15 tunnels through the Sierra Nevada Mountains. It took Chinese workers on the Central Pacific fifteen months to drill and blast through 1,659 ft of rock to complete the Summit Tunnel at Donner Pass in Sierra Nevada Mountains. Summit Tunnel is the highest point on the Central Pacific track. The Central Pacific built 40 miles of snow sheds to keep blizzards from blocking the tracks. To meet their manpower needs, both railroads employed immigrants to lay the track and blast the tunnels. The Central Pacific hired more than 13,000 Chinese laborers and Union Pacific employed 8,000 Irish, German, and Italian laborers. -

Lithuanian Jews and the Holocaust

Ezra’s Archives | 77 Strategies of Survival: Lithuanian Jews and the Holocaust Taly Matiteyahu On the eve of World War II, Lithuanian Jewry numbered approximately 220,000. In June 1941, the war between Germany and the Soviet Union began. Within days, Germany had occupied the entirety of Lithuania. By the end of 1941, only about 43,500 Lithuanian Jews (19.7 percent of the prewar population) remained alive, the majority of whom were kept in four ghettos (Vilnius, Kaunas, Siauliai, Svencionys). Of these 43,500 Jews, approximately 13,000 survived the war. Ultimately, it is estimated that 94 percent of Lithuanian Jewry died during the Holocaust, a percentage higher than in any other occupied Eastern European country.1 Stories of Lithuanian towns and the manner in which Lithuanian Jews responded to the genocide have been overlooked as the perpetrator- focused version of history examines only the consequences of the Holocaust. Through a study utilizing both historical analysis and testimonial information, I seek to reconstruct the histories of Lithuanian Jewish communities of smaller towns to further understand the survival strategies of their inhabitants. I examined a variety of sources, ranging from scholarly studies to government-issued pamphlets, written testimonies and video testimonials. My project centers on a collection of 1 Population estimates for Lithuanian Jews range from 200,000 to 250,000, percentages of those killed during Nazi occupation range from 90 percent to 95 percent, and approximations of the number of survivors range from 8,000 to 20,000. Here I use estimates provided by Dov Levin, a prominent international scholar of Eastern European Jewish history, in the Introduction to Preserving Our Litvak Heritage: A History of 31 Jewish Communities in Lithuania. -

The Migration of Lithuanian Jews to the United States, 1880 – 1918, and the Decisions Involved in the Process, Exemplified by Five Individual Migration Stories

Nathan T. Shapiro Hofstra University Department of Global Studies and Geography The Migration of Lithuanian Jews to the United States, 1880 – 1918, and the Decisions Involved in the Process, Exemplified by Five Individual Migration Stories Honors Thesis in Geography Advisor: Dr. Kari B. Jensen Shapiro 1 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 2 Jews in Lita and Reasons for Their Emigration According to the Literature ..................... 5 Migration Theory .............................................................................................................. 11 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 14 Case studies: Five Personal Migration Stories .................................................................. 16 Concluding Remarks ......................................................................................................... 35 Endnote ............................................................................................................................. 39 Bibliography ..................................................................................................................... 40 Appendix ........................................................................................................................... 43 Figure 1: Europe 1871 ...................................................................................................... -

Fort Omaha Balloon School: Its Role in World War I

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Fort Omaha Balloon School: Its Role in World War I Full Citation: Inez Whitehead, "Fort Omaha Balloon School: Its Role in World War I," Nebraska History 69 (1988): 2-10. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1988BalloonSchool.pdf Date: 7/30/2013 Article Summary: The captive balloon, used as an observation post, gave its World War I handlers a unique position among veterans. Fort Omaha became the nation's center for war balloon training, home to the Fort Omaha Balloon School. Cataloging Information: Names: Henry B Hersey, Craig S Herbert, Charles L Hayward, Frank Goodall, Earle Reynolds, Dorothy Devereux Dustin, Milton Darling, Mrs Luther Kountze, Daniel Carlquist, Charles Brown, Alvin A Underhill, Brige M Clark, Ralph S Dodd, George C Carroll, Harlow P Neibling, H A Toulmin, Charles DeForrest Chandler, John A Paegelow, Jacob W S Wuest, -

Tom Dennison, the Omaha Bee, and the 1919 Omaha Race Riot

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Tom Dennison, The Omaha Bee, and the 1919 Omaha Race Riot Full Citation: Orville D Menard, “Tom Dennison, The Omaha Bee, and the 1919 Omaha Race Riot,” Nebraska History 68 (1987): 152-165. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/1987-4-Dennison_Riot.pdf Date: 2/10/2010 Article Summary: In the spring of 1921 Omahans returned James Dahlman to the mayor’s office, replacing Edward P Smith. One particular event convinced Omaha voters that Smith and his divided commissioners must go in order to recapture the stability enjoyed under political boss Tom “the Old Man” Dennison and the Dahlman administration. The role of Dennison and his men in the riot of September 26, 1919, remains equivocal so far as Will Brown’s arrest and murder. However, Dennison and the Bee helped create conditions ripe for the outbreak of racial violence. Errata (if any) Cataloging -

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to Proclaim MEMORIALIZING June 5

Assembly Resolution No. 347 BY: M. of A. Solages MEMORIALIZING Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to proclaim June 5, 2021, as Belmont Stakes Day in the State of New York, and commending the New York Racing Association upon the occasion of the 152nd running of the Belmont Stakes WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is one of the most important sporting events in New York State; it is the conclusion of thoroughbred racing's prestigious three-contest Triple Crown; and WHEREAS, Preceded by the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes, the Belmont Stakes is nicknamed the "Test of the Champion" due to its grueling mile and a half distance; and WHEREAS, The Triple Crown has only been completed 12 times; the 12 horses to accomplish this historic feat are: Sir Barton, 1919; Gallant Fox, 1930; Omaha, 1935; War Admiral, 1937; Whirlaway, 1941; Count Fleet, 1943; Assault, 1946; Citation, 1948; Secretariat, 1973; Seattle Slew, 1977; Affirmed, 1978; and American Pharoah, 2015; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes has drawn some of the largest sporting event crowds in New York history, including 120,139 people for the 2004 running of the race; and WHEREAS, This historic event draws tens of thousands of horse racing fans annually to Belmont Park and generates millions of dollars for New York State's economy; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is shown to a national television audience of millions of people on network television; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is named after August Belmont I, a financier who made a fortune in banking in the middle to late 1800s; he also branched out -

Potential Republicans: Reconstruction Printers of Columbia, South Carolina John Lustrea University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 Potential Republicans: Reconstruction Printers of Columbia, South Carolina John Lustrea University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Lustrea, J.(2017). Potential Republicans: Reconstruction Printers of Columbia, South Carolina. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4124 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Potential Republicans: Reconstruction Printers of Columbia, South Carolina By John Lustrea Bachelor of Arts University of Illinois, 2015 ___________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Public History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: Thomas Brown, Director of Thesis Mark Smith, Reader Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by John Lustrea, 2017 All Rights Reserved. ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my dad. Thanks for supporting my love of history from an early age and always encouraging me to press on. iii Acknowledgements As with any significant endeavor, I could not have done it without assistance. Thanks to Dr. Mark Cooper for helping me get this project started my first semester. Thanks to Lewis Eliot for reading a draft and offering helpful comments. Thanks to Dr. Mark Smith for guiding me through the process of turning it into an article length paper, and thanks to Dr. -

Miscellaneous Collections

Miscellaneous Collections Abbott Dr Property Ownership from OWH morgue files, 1957 Afro-American calendar, 1972 Agricultural Society note pad Agriculture: A Masterly Review of the Wealth, Resources and Possibilities of Nebraska, 1883 Ak-Sar-Ben Banquet Honoring President Theodore Roosevelt, menu and seating chart, 1903 Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation invitations, 1920-1935 Ak-Sar-Ben Coronation Supper invitations, 1985-89 Ak-Sar-Ben Exposition Company President's report, 1929 Ak-Sar-Ben Festival of Alhambra invitation, 1898 Ak-Sar-Ben Horse Racing, promotional material, 1987 Ak-Sar-Ben King and Queen Photo Christmas cards, Ak-Sar-Ben Members Show tickets, 1951 Ak-Sar-Ben Membership cards, 1920-52 Ak-Sar-Ben memo pad, 1962 Ak-Sar-Ben Parking stickers, 1960-1964 Ak-Sar-Ben Racing tickets Ak-Sar-Ben Show posters Al Green's Skyroom menu Alamito Dairy order slips All City Elementary Instrumental Music Concert invitation American Balloon Corps Veterans 43rd Reunion & Homecoming menu, 1974 American Biscuit & Manufacturing Co advertising card American Gramaphone catalogs, 1987-92 American Loan Plan advertising card American News of Books: A Monthly Estimate for Demand of Forthcoming Books, 1948 American Red Cross Citations, 1968-1969 American Red Cross poster, "We Have Helped Have You", 1910 American West: Nebraska (in German), 1874 America's Greatest Hour?, ca. 1944 An Excellent Thanksgiving Proclamation menu, 1899 Angelo's menu Antiquarium Galleries Exhibit Announcements, 1988 Appleby, Agnes & Herman 50 Wedding Anniversary Souvenir pamphlet, 1978 Archbishop -

Omaha Beach out of Derby with Entrapped Epiglottis

THURSDAY, MAY 2, 2019 WEDNESDAY’S TRACKSIDE DERBY REPORT OMAHA BEACH OUT OF by Steve Sherack DERBY WITH ENTRAPPED LOUISVILLE, KY - With the rising sun making its way through partly cloudy skies, well before the stunning late scratch of likely EPIGLOTTIS favorite Omaha Beach (War Front) rocked the racing world, the backstretch at Churchill Downs was buzzing on a warm and breezy Wednesday morning ahead of this weekend’s 145th GI Kentucky Derby. Two of Bob Baffert’s three Derby-bound ‘TDN Rising Stars’ Roadster (Quality Road) and Improbable (City Zip) were among the first to step foot on the freshly manicured surface during the special 15-minute training window reserved for Derby/Oaks horses at 7:30 a.m. Champion and fellow ‘Rising Star’ Game Winner (Candy Ride {Arg}) galloped during a later Baffert set at 9 a.m. Cont. p3 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Omaha Beach & exercise rider Taylor Cambra Wednesday morning. | Sherackatthetrack CALYX SENSATIONAL IN ROYAL WARM-UP Calyx (GB) (Kingman {GB}) was scintillating in Ascot’s Fox Hill Farms’s Omaha Beach (War Front), the 4-1 favorite for G3 Pavilion S. on Wednesday. Saturday’s GI Kentucky Derby Presented by Woodford Reserve, Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. will be forced to miss the race after it was discovered that he has an entrapped epiglottis. “After training this morning we noticed him cough a few times,” Hall of Fame trainer Richard Mandella said. “It caused us to scope him and we found an entrapped epiglottis. We can’t fix it this week, so we’ll have to have a procedure done in a few days and probably be out of training for three weeks. -

Omaha Awareness Tours: the En Ar South Side Center for Public Affairs Research (CPAR) University of Nebraska at Omaha

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Publications Archives, 1963-2000 Center for Public Affairs Research 1979 Omaha Awareness Tours: The eN ar South Side Center for Public Affairs Research (CPAR) University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/cparpubarchives Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, and the Public Affairs Commons Recommended Citation (CPAR), Center for Public Affairs Research, "Omaha Awareness Tours: The eN ar South Side" (1979). Publications Archives, 1963-2000. 107. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/cparpubarchives/107 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Public Affairs Research at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications Archives, 1963-2000 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Near south Side Tour 1 JACKSON I -- r;;;;f BEGIN ~ JONES - v \\\ ~ LEAVENWORTH ~ ~ •2 I j MARCY -=" ::::;._ ~ n MASON :.......!.. ~'~ ~ ~ ~ So o~o.35o ;~ PACIFIC 36e Be •7 .. J ... 9• ... 37° aB as• •40 1 •10 ~ 12o oll PIERCE ...,n. ~ 13• END •72~ 42° n 43• ®"'i~ 68 .. ~ @ 34• ~~ ~ ~ ,. ~ - ..85 + 6656 :J ® •16 ~D. • + 32• :"·:. ~ WILLIAM .:! 58 57155 31° 17• 59 30• 19o Wolllworth Ave lt18 "~ 54 :J 20• ~hiogton •S1 • PINE " 29° ® .. It®~ v,t "E " M 4~ •44 "'\: \ J 28o 22o HICKORY )' 27• •23 Wau1u1 .. It ~ ,. ,;; \ J CENTER -5 ,;; ~ ~ ,;; ,;; vi vi ~ ,;; '"" -5 -5 -5 ·S -5 -5 C•w; il® \ ~ N g ~ ~ ~ .. ~ " J •47 DORCAS 26o 4~ J 25• - MARTHA @ ,----- ~ ~ ~ I ~ ,. ~ CASTELAR @ I I •I ARBOR I :J "@ VINTON •£1- - - - ;:I 4 . -

The Mitzvah of Bikur Cholim Visiting the Sick Part 1

Volume 10 Issue 9 TOPIC The Mitzvah of Bikur Cholim Visiting the Sick Part 1 SPONSORED BY: KOF-K KOSHER SUPERVISION Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita HALACHICALLY SPEAKING All Piskei Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita are Halachically Speaking is a reviewed by Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita monthly publication compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits, a former chaver kollel of Yeshiva SPONSORED: Torah Vodaath and a musmach of Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita. Rabbi Lebovits currently works as the Rabbinical Administrator for the KOF-K Kosher Supervision. SPONSORED: Each issue reviews a different area of contemporary halacha with an emphasis on practical applications of the principles discussed. Significant time is spent ensuring the inclusion of all relevant shittos on each topic, as well as the psak of Harav Yisroel Belsky, Shlita on current issues. Halachically Speaking wishes all of its readers and WHERE TO SEE HALACHICALLY Klal Yisroel a SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is distributed to many shuls. It can be seen in Flatbush, Lakewood, Five Towns, Far Rockaway, and Queens, The Design by: Flatbush Jewish Journal, baltimorejewishlife.com, The Jewish Home, chazaq.org, and SRULY PERL 845.694.7186 frumtoronto.com. It is sent via email to subscribers across the world. SUBSCRIBE To sponsor an issue please call FOR FREE 718-744-4360 and view archives @ © Copyright 2014 www.thehalacha.com by Halachically Speaking The Mitzvah of Bikur Cholim – Visiting the Sick Part 1 any times one hears that a person he knows is not well r”l and he wishes to go Mvisit him in the hospital or at home.