Melati Suryodarmo's Exergie Butter Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Art

(hard cover) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Master of Arts Fine Arts 2006 LASALLE-SIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS (blank page) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts Singapore May, 2006 ii Accepted by the Faculty of Fine Arts, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts). Vincent Leow Studio Supervisor Adeline Kueh Thesis Supervisor I certify that the thesis being submitted for examination is my own account of my own research, which has been conducted ethically. The data and the results presented are the genuine data and results actually obtained by me during the conduct of the research. Where I have drawn on the work, ideas and results of others this has been appropriately acknowledged in the thesis. The greater portion of the work described in the thesis has been undertaken subsequently to my registration for the degree for which I am submitting this document. Lee Wen In submitting this thesis to LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations and policies of the college. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made available and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. This work is also subject to the college policy on intellectual property. -

Art of Tang Da Wu

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Body and communication : the ‘ordinary’ art of Tang Da Wu Wee, C. J. Wan‑Ling 2018 Wee, C. J. W.‑L. (2018). Body and communication : the ‘ordinary’ artof Tang Da Wu. Theatre Research International, 42(3), 286‑306. doi:10.1017/S0307883317000591 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/144518 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307883317000591 © 2018 International Federation for Theatre Research. All rights reserved. This paper was published by Cambridge University Press in Theatre Research International and is made available with permission of International Federation for Theatre Research. Downloaded on 27 Sep 2021 10:02:22 SGT Accepted and finalized version of: Wee, C. J. W.-L. (2018). ‘Body and communication: The “Ordinary” Art of Tang Da Wu’. Theatre Research International, 42(3), 286-306. C. J. W.-L. Wee [email protected] Body and Communication: The ‘Ordinary’ Art of Tang Da Wu Abstract What might the contemporary performing body look like when it seeks to communicate and to cultivate the need to live well within the natural environment, whether the context of that living well is framed and set upon either by longstanding cultural traditions or by diverse modernizing forces over some time? The Singapore performance and visual artist Tang Da Wu has engaged with a present and a region fractured by the predations of unacceptable cultural norms – the consequences of colonial modernity or the modern nation-state taking on imperial pretensions – and the subsumption of Singapore society under capitalist modernization. Tang’s performing body both refuses the diminution of time to the present, as is the wont of the forces he engages with, and undertakes interventions by sometimes elusive and ironic means – unlike some overdetermined contemporary performance art – that reject the image of the modernist ‘artist as hero’. -

Press Release【The 12Th the Benesse Prize Awarded to Singapore

【Press release】 Jan.14,2020 Benesse Holdings, Inc. Representative Director and President CEO Tamotsu Adachi The 12th the Benesse Prize Awarded to Singapore Biennale 2019 Artist Amanda Heng The 12th Benesse Prize was awarded to Ms. Amanda Heng of Singapore by Benesse Holdings, Inc. (“Benesse”: Headquartered in Okayama City, Okayama Prefecture, Japan; Representative Director and President, CEO: Tamotsu Adachi) and the Singapore Art Museum (SAM). The award ceremony was held at the National Gallery Singapore on January 11th, 2020. The 12th Benesse Prize was presented in collaboration with SAM, the organizer of Singapore Biennale 2019 and was open to all artists participating in the Biennale. The following five shortlisted artists were selected by an international jury and announced at the SB2019 media conference in November 2019: Amanda Heng (Singapore), Dusadee Huntrakul (Thailand), Haifa Subay (Yemen), Hera Büyüktaşçıyan (Turkey), and Robert Zhao Renhui (Singapore). The final selection took place at Benesse Art Site Naoshima, where the winner was selected from the shortlist. The prize is awarded to an outstanding artist chosen from the artists participating in the Biennale. The prize recognizes an artist whose work embodies an experimental and critical spirit, beyond conventional practice, and who demonstrates the potential of developing an artistic reflection around the theme of “Benesse” (Well-Being). Ms. Heng will be commissioned to either create a work to be exhibited at Benesse Art Site Naoshima, Japan, or have her artwork become part of its collection in the future, in addition to receiving a cash prize of JPY 3,000,000 (including a visit to Benesse Art Site Naoshima) from Benesse. -

Conceptual Strategies in Southeast Asian Art a Local Narrative

conceptual strategies in Southeast Asian Art a local narrative introduction Beuys, but also asserting the autonomy of regional conceptual prac- In his review of the Southeast Asian art exhibition of 2010 Making History tices.5 That exhibition’s approach, in its differentiated understanding Tony Godfrey, the author of Conceptual Art, assesses works by Alwin of globalism, recognition of local conditions and histories, broad view Reamillo (b.1964), Mella Jaarsma (b.1960), Vasan Sitthiket (b.1957), of dematerialization, and acceptance of non-homogenous institutional Tang Da Wu (b.1943), Nge Lay (b.1979), Green Zeng (b.1972), and critique, offers a welcome perspective on conceptual modes of non- Bui Cong Khanh (b.1972) as difficult to read, “... its (the exhibition’s) Euramerica.6 The mission here then, before establishing parallels or weakness is the indirect allusions that they (the artists) use to make even beginning to speak of displacing or adding on to as does Okwui their point...”. Yet it is emphatically the case that the practices of these Enwezor, is to start with the art itself and from there capture the nature acknowledged regional talents are marked by conceptual strategies, and possible antecedents of conceptual tactics employed by Southeast their visual languages chosen accordingly.1-3 Godfrey frames his review Asian practitioners, thus affording what John Clark calls a self-disen- with a survey of history painting, an academic genre instrumentalised by tanglement involving Asian contextualization.7-8 nineteenth century Europe’s -

The Next Gen Art Collectors 2021

COLLECTORS 1 THE NEXT COLLECTORS REPORT 2021 3 LARRY’S LIST is pleased to present The Next Gen that have not yet been acknowledged or made visible For us, size wasn’t a main consideration. Indeed, not a blue-chip artist will most likely generate more “likes” FOREWORDArt Collectors Report. Here, we continue our mission on a global scale. We want to share their stories and everyone listed has a large collection; charmingly, the than an unknown artist in an equally brilliant interior of monitoring global happenings, developments and thoughts. Next Gen often have collections in the making. The setting. But we still try to balance it and set aside any trends in the art world—particularly in the contemporary We also consider LARRY’S LIST as a guide and tool process is a development that happens over years care about the algorithm. art collector field—by looking extensively at the next for practitioners. We share and name collectors, those and so a mid-20-year-old collector may not yet be at generation of young art collectors on the scene. Over people who are buying art and contributing to the the same stage in their collection as someone in their Final words the past few months, we have investigated and profiled art scene. The Next Gen Art Collectors Report is a late 30s. I would like to express my gratitude to all the collectors these collectors, answering the questions central to this resource for artists, galleries, dealers, a general art- The end result of our efforts is this report listing over we exchanged with in the preparation of this report topic: Who are these collectors founding the next art interested audience and, of course, peer collectors. -

Classic Contemporary Contemporary Southeast Asian Art from the Singapore Art Museum Collection

CLASSIC CONTEMPORARY CONTEMPORARY SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART FROM THE SINGAPORE ART MUSEUM COLLECTION 29 JANUARY TO 2 MAY 2010 ADVISORY: THIS PUBLICATION CONTAINS IMAGES OF A GRAPHIC NATURE ABOUT THE EXHIBITION Classic Contemporary shines the spotlight on Singapore Art Museum’s most iconic contemporary artworks in its collection. By playfully asking what makes a work of art “classic” or “contemporary” — or “classic contemporary” — this accessible and quirky exhibition aims to introduce new audiences to the ideas and art forms of contemporary art. A stellar cast of painting, sculpture, video, photography and performance art from across Southeast Asia are brought together and given the red-carpet treatment, and the whole of the SAM 8Q building is transformed into a dramatic stage for these stars and icons. Yet beneath the glamour, many of the artworks also probe and prod serious issues — often asking critical and challenging questions about society, nation and the history of art itself. Since its inception in 1996, SAM has focused on collecting the works of artists practicing in the region, and many of these once-emerging artists have since established notable achievements on regional and international platforms. This exhibition marks the start of SAM’s new contemporary art programming centred on enabling artistic development through the creation of exhibition and programming platforms, as well as growing audiences for contemporary art. Classic Contemporary offers an opportunity to revisit major works by Suzann Victor, Matthew Ngui, Simryn Gill, Redza Piyadasa, Jim Supangkat, Nindityo Adipurnomo, Agnes Arellano, Agus Suwage, and Montien Boonma, among others. A full programme of curatorial lectures, artist presentations, moving image screenings and performances complete the classic contemporary experience. -

A Performing Archive 17.02.17, 10�14

re.act.feminism - a performing archive 17.02.17, 1014 Search A Ebtisam Abdulaziz Marina Abramović Helena Almeida Eleanor Antin Arahmaiani Malin Arnell Oreet Ashery Augusta Atla Margarita Azurdia B Back to selection Antonia Baehr Complete Archive Maja Bajević Manon, La dame au crâne rasé, 1970s Anne Bean Anat Ben-David Renate Bertlmann Manon Document media Pauline Boudry & Das lachsfarbene Boudoir / La dame au crâne video, colour, sound, 12:10 min Renate Lorenz rasé Issue date Nisrine Boukhari 1974, 1978 / 2006 After studying commercial art and acting in Zurich, in 1974 Marijs Boulogne Tags Manon (*1946, Switzerland) began creating environments in Tania Bruguera beauty, fashion/glamour, which she plays different roles together with sometimes as femininity, in/visibility, Nancy Buchanan many as 60 extras and uses virtually all forms of modern private/public Maris Bustamante media. She was one of Switzerland’s first performance artists About the project C Archive Signature Partners and is most likely the country’s most famous. She lived in Paris MAN 1 Cabello / Carceller Imprint from 1977 to 1980 before moving back to Zurich, where she lives Shirley Cameron/ Contact and works today. Since 1998, she has been concentrating Monica Ross/ Find us on facebook mainly on installations which explore eroticism and transience, Evelyn Silver most recently in 2011 in her project "Hotel Dolores" concerned Graciela Carnevale with deserted spa hotels in the spa district of Baden, Aargau Theresa Hak Kyung (Switzerland). Cha Helen Chadwick This is a collection of TV features about, among other works, Manon’s Das lachsfarbene Boudoir (The Salmon-Coloured Chicks on Speed Boudoir), her first environment which she reconstructed for the Lygia Clark Migros Museum Zurich in 2006, and La dame au crâne rasé (The Mary Coble Woman with the Shaved Head), a series of staged photographs Colette in Paris. -

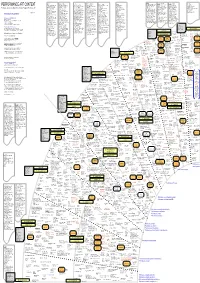

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

Annual Report 2018–19 Snapshot of the National Gallery of Australia

Annual Report 2018–19 Snapshot of the National Gallery of Australia Who we are What we do The National Gallery of Australia The Gallery provides opened to the public in October 1982 exceptional experiences of and is the Commonwealth of Australia’s rich visual arts Australia’s national cultural institution for the culture. Through the national collection, visual arts. Since it was established in 1967, it exhibitions, educational and public programs, has played a leadership role in shaping visual outreach initiatives, research and publications, arts culture across Australia and its region and infrastructure and corporate services, the continues to develop exciting and innovative Gallery is a model of excellence in furthering ways to engage people with the national knowledge of the visual arts. The Gallery art collection. makes art accessible, meaningful and vital to diverse audiences, locally, nationally and internationally. Our purpose and outcome Our staff As Australia’s pre-eminent visual staff at 30 June 2019. The Gallery arts institution, the Gallery provides 326 has an inclusive workforce, social and cultural benefits for the employing people with a disability and people community and enhances Australia’s with culturally diverse backgrounds, including international reputation. The Gallery’s one Indigenous Australians. Women represent outcome, as outlined in the Portfolio Budget 67% of the Gallery’s workforce and 50% Statements 2018–19, is ‘Increased of its Senior Management Group. Detailed understanding, knowledge and enjoyment staffing information is on pages 72–7. of the visual arts by providing access to, and information about, works of art locally, nationally and internationally’. Our collection Our supporters Over nearly half a century of The Gallery nurtures strong collecting, the Gallery has achieved relationships with external extraordinary outcomes in acquiring stakeholders, such as artists and and displaying Australian and international art. -

![TIES of HISTORY Art in Southeast Asia Amanda Heng Walking the Stool [Detail] 1999-2000 3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1118/ties-of-history-art-in-southeast-asia-amanda-heng-walking-the-stool-detail-1999-2000-3-3871118.webp)

TIES of HISTORY Art in Southeast Asia Amanda Heng Walking the Stool [Detail] 1999-2000 3

TIES OF HISTORY Art in Southeast Asia Amanda Heng Walking the Stool [detail] 1999-2000 3 TIES OF HISTORY TIES OF HISTORY EXHIBITION PUBLICATION Curation Project Management Team Documentation Editing Patrick D. Flores Joanna Marie Batinga Kristian Jeff Agustin Patrick D. Flores Toni Rose Billones A.g. De Mesa Project Coordination Mikka Ann Cabangon Ferlyn Landoy Copyediting Karen Capino Trisha Lhea Lozada Neil Lee Thelma Arambulo Sheree Mangunay Curatorial Coordination Louise Marcelino Design Carlos Quijon, Jr. Ma. Cristina Orante Board of Advisors Dino Brucelas Nolie Seneres Ahmad Mashadi Project Management Jeanne Melissa Severo Khim Ong Photography Aurea Brigino Manuel Agustin Z. Singson Loredana Pazzini- A.g. De Mesa Loen Vitto Paracciani Grace Samboh Publication Coordination Carlos Quijon, Jr. TIES OF HISTORY ©2019 by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), through the Dalubhasaan Para sa Edukasyon sa Sining at Kultura (DESK), and the Office of Senator Loren Legarda. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission. Copyright of all images is owned by the artists, reproduced with the kind permission of the artists and/or their representatives. Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders and to ensure that all information presented is correct. Some of the facts in this volume may be subject to debate or dispute. If proper copyright acknowledgment has not been made, or for clarifications and corrections, please contact the publishers and we will correct the information in future reprinting, if any. PRECEDING: Chris Chong Chan Fui Botanic PIT#7 S Nymphoides Indica (Lotus) [detail] 2013 09 THE ARTISTIC PROVINCE OF A POLITICAL REGION Patrick D. -

KLARA SCHILLIGER & VALERIAN MALY Selected Works 1991

KLARA SCHILLIGER & VALERIAN MALY Selected Works 1991 - 2011 1 Selected Works Curriculum Vitae 03 - 13 In Gold Geritzte Ranken 2008 115 - 118 volagratis : YAOUNDÉ NON È UN BEL POSTO 2019 14 - 17 arrival zone – vapour trail – departure zone 2007 119 - 136 a e i o u V Helix – snailwatching karaoke 2016 18- 24 MarksBlond Blaster 2007 137 - 140 R U M O U R S induced by I G I N G 25 - 30 Seidenschrei – Le Dernier Cri 2006 139 - 146 P L E S U N G A N – 181’440 permutations 2014 31 - 36 Hello ! 2005 141- 154 P L E S U N G A N – 181’440 permutations 2014 37 - 41 The compost heap in us – (100 glasses of booze ) 2004 155 - 158 TTAALLIINN 2013 42 - 45 Mit fremden Federn schmücken 2004 159 - 166 Nairsünalv 2011 46 - 55 I Need You 2004 167- 172 Monument Ginger Society Tirana 2011 56 - 61 Stabile Runde 2004 173- 176 Buch Jonah 2010 62- 67 Sarabande Double 2002 177- 182 Monument Ginger Society Thun 2010 68 - 93 Glas Stern 2000 183- 188 Uwaga Uwaga, Szcz ! Achtung Achtung, Szcz ! 2009 94 - 100 Wassern 1998 189- 193 Raum, fliegend 2009 101- 104 Ohne Titel 1991 194 - 199 Dianes Chasseresses 2009 105 - 110 Impressum 200 Gerölle 2008 / 2009 111 - 114 Epilog 201 2 Klara Schilliger & Valerian Maly Klara Schilliger (*1953 in Sursee/ Switzerland) and Valerian Maly (*1959 in Tübingen/ Germany) work and live together since 1984. Their artistic field is Perfor- mance Art and Installation. For some of their works they use the term of InstallAction (they learned from Alastair Mac Lennan) and which they use mostly for (long duration-) performances where the public is directly part and participating. -

Reenacting History: Collective Actions and Everyday Gestures

ALLORA & CALZADILLA Half Mast, Full Mast, 2010 2 Channel HD video projection, color, 21'11" Courtesy of the artists and Lisson Gallery, London Photo by Ken ADLARD © ALLORA & CALZADILLA Reenacting History: Collective Actions and Everyday Gestures 22 September 2017 – 21 January 2018 MMCA Gwacheon The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA; Director: Bartomeu Mari) presents the exhibition Reenacting History: Collective Actions and Everyday Gestures from Friday, September 22, 2017, to Sunday, January 21, 2018, in the Circular Gallery 1 at MMCA, Gwacheon. Featuring thirty-eight artists and collectives working in and outside of Korea, Reenacting History is a large-scale international special exhibition that focuses on how the body and gestures have revealed the current social and cultural contexts and interests as an artistic medium since the 1960s until today. The body is a medium through which “I” build a relationship with others and encounter different situations in the world, as well as a social space in which the politics of reality such as power, capital, and knowledge are at work. As such, the body has been a major existence throughout the entire scope of human life, and numerous artists have employed the body as an artistic medium since the 1960s. Based on various ways in which bodily gestures, as an artistic medium, approach and artistically react to our life stories, the exhibition is divided into three parts. Part 1, titled Performing Collective Memory and Culture, illuminates performance works, which have attempted to reenact history by restructuring through gestures the collective memories and cultural heritage of a community.