Airline Entry and Competition in New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Qantas Counterfactual Paul Edwards 18 August 2003

The Qantas Counterfactual Public Session Paul Edwards 18 August 2003 Counterfactual • strategySecure and develop Australasian home base. • Competitive position is essential. • Natural extension of Qantas long term commitment to New Zealand 4 International 4 Domestic. Domestic New Zealand• Qantas is in the relatively early stages of domestic New Zealand expansion. • Qantas has maintained some form of presence in domestic New Zealand for 10 years. 4 Preferred selling arrangement with Ansett New Zealand (1990) 4 Franchise arrangement with Tasman Pacific (2000) 4 Qantas operations (May 2001) Commitment to Domestic New • Expansion plans slowed due to events outsideZealand Qantas control 4 Collapse of Ansett Australia in September 2001. • Implementation of the counterfactual is already in progress. 4 Jetconnect established in June 2001 4 Received AOC in October 2002 4 Five-aircraft operation by November 2002 4 Sixth aircraft arrived in May 2003 4 Wellington base established June 2003 Reasons for growing in Domestic New • Need to protectZealand and build network profit. • Home market. • Need to build frequency. • Current revenue share does not match capacity share (“share gap”). Plans for Domestic • New fareNew structure already Zealand implemented. • Continue with plans to expand the business. • Review of product and network. • Discuss further in confidential session. Plans for the • Introduction ofTasman more efficient aircraft 4Operate all Auckland and most Christchurch services with wide-bodied aircraft 4Operation of some 737s using Jetconnect. • Review fare structure. • Discuss above and other international routes further in confidential session. Airline Planning Group New Zealand Presence Analysis Overview of ‘City Presence’ What passengers value • Competitive fares. • Minimum travel time to destination. -

Wellington International Airport Limited Presentation to Commerce Commission Conference | 21 August 03 | Page 2

Presentation to Commerce Commission Conference | 21 August 2003 Presentation by John Sheridan Chief Executive, Wellington International Airport Limited Presentation to Commerce Commission Conference | 21 August 03 | page 2 Introduction Aviation experience 16 years in the aviation industry including 12 years in senior airline positions and over 4 years as the Chief Executive of Wellington International Airport The interest of WIAL in the application WIAL is directly affected by the outcome Objective To clearly demonstrate the critical importance of competition for both market growth and the continuing introduction of new product and services Presentation to Commerce Commission Conference | 21 August 03 | page 3 Domestic Market: 1987 - present Ansett New Zealand commenced operations in 1987 with some immediate outcomes being: Upgraded terminal facilities The introduction of aerobridges Improved service standards. A few examples: Catering on the aircraft, lounge facilities & valet parking Most importantly Ansett New Zealand meant competition and the availability of discount fares. Average fare dilution increased from 15% to 35%-40% on those sectors where Ansett New Zealand competed The stimulation of market growth Domestic passenger numbers through Wellington airport increased by 20% in the first two years after Ansett New Zealand started operations Presentation to Commerce Commission Conference | 21 August 03 | page 4 Domestic Market: 1987 - present In the period 1995 through to November 2002 there were few initiatives in the market, with the result that growth averaged 1.3% per year only over this period. This period included the Ansett pilots dispute in 1999, the receivership of Tasman Pacific in 2001, the start-up of Qantas Airways domestic services in New Zealand and the growth of Origin Pacific. -

Annual Report 20 07 Aviation Industry Association of New Zealand (Inc) Contents

AVIATION INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION OF NEW ZEALAND (INC) Annual Report 20 07 Aviation Industry Association of New Zealand (Inc) Contents General Association Officers 2 Past Officers/Life Members 3 President’s Report 5 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 13 Financial Statements 18 AIA Annual Conference Report 28 Aviation Training Report 52 Aviation Services Ltd 55 AIRCARE Annual Report 2007 57 List of Advertisers 60 Divisional Chair Reports NZAAA (Agricultural Aviation) 31 Air Rescue/Air Ambulance 34 Air Transport 35 Education and Research 37 Engineering 38 Flight Training 40 Annual Report Helicopter 42 Supply & Services 44 Tourist Flight Operators 49 20 Cover Photo: The Auckland Rescue Helicopter Trust’s BK117B2 ZK HLN over central Auckland being flown by the Trust’s Chief Pilot Dave Walley. The Single Pilot IFR, NVG Configured helicopter came into service with the Trust on 01January 2007 and completed its 300 hr check 01 July 2007. 07 ANNUAL REPORT 2007 2 Association Officers 2006–2007 Council Head Office President: Chief Executive: W.J. Funnell, Helicopter Services BOP Ltd I.S. King Vice-Presidents: W.P. Taylor, Eagle Airways Ltd Office Manager: W. Sattler, Ardmore Flying School Ltd P.A. Hirschman Immediate Past President: Membership Liaison Manager: D. Thompson, Dennis Thompson International Ltd D. Watson Councillors Technical Advisors: J. McGregor M. Chubb J. Lusty K. MacKenzie D. Webb B. Wyness P. Garden D. Lyon D. Morgan R. Wikaira F. Douglas D. Horrigan P. Mackay A. Peacock NZAAA Executive Officer: Divisional and Branch Chair J.F. Maber Agricultural Aviation Division Office Address: Chair: K.J. MacKenzie, MacKenzie Aviation Ltd Level 5 Deputy Chair & South Island Branch Chair: Agriculture House T. -

Air New Zealand Adjusted Its Business Quickly to Manage the Impact of Covid-19

Media release 27 August 2020 Air New Zealand adjusted its business quickly to manage the impact of Covid-19 Air New Zealand today announces its 2020 result, affirming the unprecedented effect of the Covid- 19 pandemic on its business and the global aviation industry following extensive travel and border restrictions which commenced from March. Air New Zealand is reporting a loss before other significant items and taxation of $87 million1 for the 2020 financial year, compared to earnings of $387 million in the prior year. Despite reporting a strong interim profit of $198 million2 for the first six months of the financial year, and seeing positive demand on North American and regional routes early in the second half, Covid- related travel restrictions resulted in a 74 percent drop in passenger revenue from April to the end of June compared to the prior year, which drove the airline’s operating losses. Statutory losses before taxation, which include $541 million of other significant items, were $628 million, compared to earnings of $382 million last year. Non-cash items of $453 million reflected most of the other significant items, including the $338 million aircraft impairment charge related to grounding of the Boeing 777-200ER fleet for the foreseeable future. The airline has responded to this crisis with urgency, including securing additional liquidity, structurally reducing its cost base and deferring significant capex spend, whilst ensuring that the business remains well positioned to grow profitably when travel restrictions are eventually removed and customer demand returns. Quick and decisive action in response to Covid-19 Air New Zealand’s Chairman Dame Therese Walsh says she is proud of the way the business has responded to this crisis, acting with speed and agility to lower the cost base, and pivoting quickly to ramp up domestic and cargo services to help keep the New Zealand economy moving. -

Flying High on Schwank's Infrared Efficiency a Schwank Case Study

Schwank Case Study: Flying High on Schwank‘s Infrared Efficiency “The heating levels in our facilities are very comfortable and cope well with the chan- ges in weather that we experi- ence. We are very happy with The Company The Issue Schwank”. Air Nelson is a wholly owned sub- Energy efficiency, longevity, control- sidiary of Air New Zealand operating lability, quick reaction times and flexi- Mark Butchart, under the Air New Zealand brand. bility were all extremely important. Production Manager, The airline was started in 1976 and Planes coming in and out regularly Air Nelson began its first scheduled service in create high air changes due to the 1984 to connect to Wellington. The frequent door openings. Furthermore, network then grew to include Nelson, cold incoming airplanes act like ice Wellington, Auckland, Christchurch blocks making the environment very and other domestic destinations. challenging for conventional heating systems. To compensate for these In 1995 Air New Zealand purchased sudden “shock” heat losses and to Air Nelson, which now operates provide homogenous heat distribu- 23 Bombardier Q300s being the tion in the hangars was an imperative world’s largest operator of this type requirement for the Air New Zealand of aircraft. Air New Zealand recently technical department. invested 30 million dollars at Nel- son airport in order to expand on Air New Zealand’s appointed consult- its infrastructure to include modern ing engineers, Pacific Consultants maintenance facilities for its com- from Wellington, then had the task of muter airlines. Today also the entire specifying a system that was suit- ATR-72 aircraft fleet of Mount Cook able to meet the requirements for Airline, also part of the Air New Zea- both hangars. -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

11. Working with the Airlines in the Australasia-Pacific Region

11 Working with the airlines in the Australasia-Pacific region With my tenure at the new Unisys on shaky ground, I asked former colleagues if they knew of a job opportunity for someone with my skill set. I certainly wanted to stay in the Asia-Pacific area. New Zealand, as a relatively small country, did not present any immediate opportunities other than working with a computer consultancy or setting up on my own, and I was not keen on the latter. Richard Hawkins had left Unisys in Hong Kong and joined the Société Internationale de Télécommunications Aéronautiques (SITA). He had already spoken to SITA on my behalf and advised me to call Ms Irene Legay in SITA’s Hong Kong office. The SITA opportunity was attractive. I knew the organisation and had overseen its Sperry installations in Bangkok and Jakarta. I knew SITA to be technically aggressive. It used Sperry second-level communication processors, without mainframes, for its communications network, and I had recently liaised with SITA when the New Zealand Defence Department had contemplated a similar application. After the end of World War II, international telephone lines had been hard to obtain, so the airlines decided it would be to their advantage to pool resources. SITA was set up to control those resources and provide additional services. In the 1980s, as SITA approached its 40th anniversary, director general Claude Lalanne had instructed McKinsey & Company, as consultants, to investigate the strategies that would keep SITA viable for the next 40 years. McKinsey had recommended that SITA set up 223 ALSO INNOVatoRS a sales and marketing operation — a group of 32 people — to optimise its potential. -

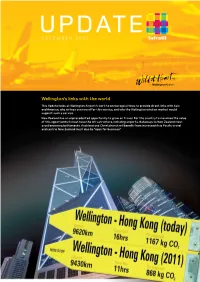

Wellington's Links with the World

DECEMBER 2007 Wellington’s links with the world This Update looks at Wellington Airport’s work to encourage airlines to provide direct links with Asia and America, why airlines can now offer this service, and why the Wellington aviation market would support such a service. New Zealand has an unprecedented opportunity to grow air travel. For the country to maximise the value of this opportunity it must have the infrastructure, including airports. Gateways to New Zealand must avoid becoming bottlenecks. Auckland and Christchurch will benefit from increased Asia Pacific travel and central New Zealand must also be “open for business”. www.Infratil.com Air services matter Global Economic Activity (GEA) and world population within a 3.5 hour flying time PARIS CHICAGO 26% of world GEA 15% of world 32% of 25% of population HONG KONG world GEA world GEA 42% of world 7% of world population population WELLINGTON 1% of world GEA 0.4% of world population New Zealand is the furthest away place in the world. Draw a circle on a map to show 3.5 hours flying time from New Zealand and the circle captures 0.4% of the world’s population. The benefits and barriers of better connectivity are apparent from doing the same exercise centred on Hong Kong (42% of the world’s population and 32% of global economic activity), Paris (15% of the people, 26% of the economy) and Chicago (7% of the people and 25% of the world’s economy). A direct Wellington-Hong Kong air service would reduce travel time by at least three hours (six to seven if the service is via Sydney rather than Auckland). -

Amendments to Civil Aviation Rule Part 121: Air Operations (Large Aeroplanes) Agency Disclosure Statement

Regulatory Impact Statement for Amendments to Civil Aviation Rule Part 121: Air Operations (Large Aeroplanes) Agency disclosure statement 1. This Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) has been prepared by the Ministry of Transport with assistance from the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). It provides an analysis of options to: improve the safety of large aeroplane operations by ensuring flight crew assignment, training and competency requirements align with International Civil Aviation Organization standards (ICAO); ensure a clearer and more transparent application of Part 121 by reducing or removing unnecessarily restrictive rule requirements which, in some cases has forced industry to incur needless compliance costs. 2. There is some uncertainty concerning the analysis because New Zealand has not experienced a significant accident during training or competency assessment in large aeroplanes since 19661. Parts of the regulatory analysis are therefore based on international accident data which has identified human factors as a significant safety risk.2 3. The regulatory proposal will impose compliance costs on some operators of large sized aeroplanes. However, the proposed amendment should reduce costs to operators by removing the need to seek exemptions and providing increased flexibility to achieve compliance. Our assumption is that the proposed rule amendments will result in reduced safety risks and improved safety outcomes for New Zealand‘s travelling public. Industry unanimously support the preferred option to amend Part 121. 4. The proposal will not impair private property rights, market competition, or the incentives on businesses to innovate and invest, or override any of the fundamental common law principles. The proposal is consistent with our commitments in the Government statement Better Regulation, Less Regulation. -

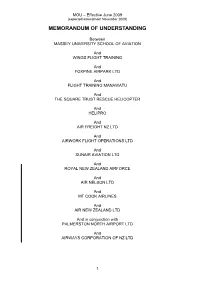

Memorandum of Understanding

MOU – Effective June 2009 (expected amendment November 2009) MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING Between MASSEY UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF AVIATION And WINGS FLIGHT TRAINING And FOXPINE AIRPARK LTD And FLIGHT TRAINING MANAWATU And THE SQUARE TRUST RESCUE HELICOPTER And HELIPRO And AIR FREIGHT NZ LTD And AIRWORK FLIGHT OPERATIONS LTD And SUNAIR AVIATION LTD And ROYAL NEW ZEALAND AIRFORCE And AIR NELSON LTD And MT COOK AIRLINES And AIR NEW ZEALAND LTD And in conjunction with PALMERSTON NORTH AIRPORT LTD And AIRWAYS CORPORATION OF NZ LTD 1 MOU – Effective June 2009 (expected amendment November 2009) 1 PARTIES 1.1 Massey University School of Aviation is a flight training organisation located at Palmerston North Airport 1.2 Wings Flight Training is a flight training organisation also located at Palmerston North Airport. 1.3 Foxpine Airpark Ltd is an airport operator and a flight training organisation and is the owner of and operating from Foxpine Airport. 1.4 Flight Training Manawatu is a flight training organisation located at Feilding Aerodrome 1.5 The Square Trust Rescue Helicopter is located at the Palmerston North Hospital. 1.6 Helipro is a commercial helicopter operator also involved in flight training and has a base located at the Palmerston North Airport. 1.7 Air Freight NZ Ltd is a commercial operator based in Auckland and operates freight aircraft types Convair 580 / 5800 under the call sign of “Air Freight” 1.8 Airwork Flight Operations Ltd is a commercial operator based in Auckland and operates both F27 and Metro aircraft types on freight operations under the call sign of “Post”. -

Download Issue 60 Complete

10th Anniversary Issue KiwiFlyer TM Magazine of the New Zealand Aviation Community Issue 60 2018 #5 Aerobatic Sequencing $ 7.90 inc GST ISSN 1170-8018 Full Noise 35 returns to Reno Annual Supply & Maintenance Guide Air to Air at RIAT and more Products, Services, News, Events, Warbirds, Recreation, Training and more. KiwiFlyer Issue 60 2018 #5 From the Editor Features Welcome to the 10th Anniversary Edition of 8 Seven Days in September KiwiFlyer. It seems that an entire decade has Graeme Frew and the Full Noise 35 passed since Issue number one rolled off the Team return to race again at Reno. printing presses and into the post boxes of aircraft operators throughout New Zealand. 22 Tecnam’s Extensive Range 8 We’ve reflected about this in a column on the next Ruth Allanson outlines the range of page. Suffice to say producing each issue is still aircraft she now represents in NZ. an enjoyable endeavour and we plan to keep 30 Aerobatic Sequence Design going for quite some time yet. Grant Benns discusses some detailed This issue is another blockbuster effort at 80 insights into aerobatic sequence pages, thanks to the inclusion of our annual design, plus a helpful app. Supply and Maintenance feature which contains 38 Battle of Britain Memorial Flight numerous profiles and advertisements from all Gavin Conroy writes about a special manner of supply and maintenance providers occasion during his trip to the UK. throughout the country. 42 Guide to Supply and Maintenance 63 A highlight of this issue is the story of Graeme Our annual profile of major Frew and his Full Noise 35 team’s return to the providers throughout New Zealand. -

New Zealand Adjusted Its Business Quickly to Manage the Impact of Covid-19

Media release 27 August 2020 Air New Zealand adjusted its business quickly to manage the impact of Covid-19 Air New Zealand today announces its 2020 result, affirming the unprecedented effect of the Covid- 19 pandemic on its business and the global aviation industry following extensive travel and border restrictions which commenced from March. Air New Zealand is reporting a loss before other significant items and taxation of $87 million1 for the 2020 financial year, compared to earnings of $387 million in the prior year. Despite reporting a strong interim profit of $198 million2 for the first six months of the financial year, and seeing positive demand on North American and regional routes early in the second half, Covid- related travel restrictions resulted in a 74 percent drop in passenger revenue from April to the end of June compared to the prior year, which drove the airline’s operating losses. Statutory losses before taxation, which include $541 million of other significant items, were $628 million, compared to earnings of $382 million last year. Non-cash items of $453 million reflected most of the other significant items, including the $338 million aircraft impairment charge related to grounding of the Boeing 777-200ER fleet for the foreseeable future. The airline has responded to this crisis with urgency, including securing additional liquidity, structurally reducing its cost base and deferring significant capex spend, whilst ensuring that the business remains well positioned to grow profitably when travel restrictions are eventually removed and customer demand returns. Quick and decisive action in response to Covid-19 Air New Zealand’s Chairman Dame Therese Walsh says she is proud of the way the business has responded to this crisis, acting with speed and agility to lower the cost base, and pivoting quickly to ramp up domestic and cargo services to help keep the New Zealand economy moving.