Impromptu in C Minor Impromptu in E-Flat Impromptu in G-Flat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Franz Schubert's Impromptus D. 899 and D. 935: An

FRANZ SCHUBERT’S IMPROMPTUS D. 899 AND D. 935: AN HISTORICAL AND STYLISTIC STUDY A doctoral document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2005 by Ina Ham M.M., Cleveland Institute of Music, 1999 M.M., Seoul National University, 1996 B.M., Seoul National University, 1994 Committee Chair: Dr. Melinda Boyd ABSTRACT The impromptu is one of the new genres that was conceived in the early nineteenth century. Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 are among the most important examples to define this new genre and to represent the composer’s piano writing style. Although his two sets of four impromptus have been favored in concerts by both the pianists and the audience, there has been a lack of comprehensive study of them as continuous sets. Since the tonal interdependence between the impromptus of each set suggests their cyclic aspects, Schubert’s impromptus need to be considered and be performed as continuous sets. The purpose of this document is to provide useful resources and performance guidelines to Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 by examining their historical and stylistic features. The document is organized into three chapters. The first chapter traces a brief history of the impromptu as a genre of piano music, including the impromptus by Jan Hugo Voŕišek as the first pieces in this genre. -

Andras Schiff Franz Schubert Sonatas & Impromptus

Andras Schiff Franz Schubert Sonatas & Impromptus -• ECM NEW SERIES Franz Schubert Vier Impromptus D 899 Sonate in c-Moll D 958 Drei Klavierstücke D 946 Sonate in A-Dur D 959 Andräs Schiff Fortepiano Franz Schubert (1797-1828) II 1-4 Vier Impromptus D899 1-3 Drei Klavierstücke D 946 Allegro molto moderato in c-Moll 9:32 Allegro assai in es-Moll 9:12 Allegro in Es-Dur 4:39 Allegretto in Es-Dur 11 :46 Andante in Ges-Dur 4:59 Allegro in C-Dur 5:31 Allegretto in As-Dur 7: 21 4-7 Sonate in A-Dur D959 5-8 Sonate in c-Moll D958 Allegro 15:45 Allegro 10:35 Andantino 7:13 Adagio 7:00 Scherzo. Allegro vivace - Trio 5:30 Menuett. Allegretto - Trio 3:04 Rondo. Allegretto 12:35 Allegro 9:13 Beethoven's sphere "Secretly, I hope to be able to make something of myself, but who can do any thing after Beethoven?" Schubert's remark, allegedly made to his childhood friendJosef von Spaun, gives us an indication of how strongly he feit himself to be in the shadow of the great composer he was too inhibited ever to approach. For his part, Beethoven cannot have been unaware of Schubert's presence in Vienna. The younger composer's first piano sonata to appear in print - the Sonata in A minor D 845 - bore a dedication to Beethoven's most generous and ardent pa tron, Archduke Rudolph of Austria. Moreover, the work was favourably reviewed in the Leipzig Al/gemeine musikalische Zeitung - a journal which Beethoven is known to have read. -

The Functions of Harmonic Motives in Schubert's Sonata Forms1 Brian

The Functions of Harmonic Motives in Schubert’s Sonata Forms1 Brian Black Schubert’s sonata forms often seem to be animated by some hidden process that breaks to the surface at significant moments, only to subside again as suddenly and enigmatically as it first appeared. Such intrusions usually highlight a specific harmonic motive—either a single chord or a larger multi-chord cell—each return of which draws in the listener, like a veiled prophecy or the distant recall of a thought from the depths of memory. The effect is summed up by Joseph Kerman in his remarks on the unsettling trill on Gß and its repeated appearances throughout the first movement of the Piano Sonata in Bß major, D. 960: “But the figure does not develop, certainly not in any Beethovenian sense. The passage... is superb, but the figure remains essentially what it was at the beginning: a mysterious, impressive, cryptic, Romantic gesture.”2 The allusive way in which Schubert conjures up recurring harmonic motives stamps his music with the mystery and yearning that are the hallmarks of his style. Yet these motives amount to much more than oracular pronouncements, arising without any apparent cause and disappearing without any tangible effect. Quite the contrary—they are actively involved in the unfolding of the 1 This article is dedicated to William E. Caplin. I would also like to thank two of my colleagues at the University of Lethbridge, Deanna Oye and Edward Jurkowski, for their many helpful suggestions during the article’s preparation. 2 Joseph Kerman “A Romantic Detail in Schubert’s Schwanengesang,” in Walter Frisch (ed.), Schubert: Critical and Analytical Perspectives, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986): 59. -

Franz Schubert

FRANZ SCHUBERT Foreword . 3 About the Composer . 3 Contents Schubert’s Piano Music . 3 About This Edition . 4 About the Music . 5 Moments Musicaux, Op . 94 (D . 780) . 5 Impromptus, Op . 90 (D . 899) . 7 Impromptus, Op . 142 (D . 935) . 9 Recommended Reading . 12 Recommended Listening . 12 Acknowledgments . 12 MOMENTS MUSICAUX, Op . 94 (D . 780) No . 1 (C major) . 13 No . 2 (A-flat major) . 16 No . 3 (F minor) . 20 No . 4 (C-sharp minor) . 22 No . 5 (F minor) . 26 No . 6 (A-flat major) . 29 IMPROMPTUS, Op . 90 (D . 899) No . 1 (C minor) . 32 No . 2 (E-flat major) . 43 No . 3 (G-flat major) . 49 No . 4 (A-flat major) . 57 IMPROMPTUS, Op . 142 (D . 935) No . 1 (F minor) . 68 No . 2 (A-flat major) . 83 No . 3 (B-flat major) . 88 No . 4 (F minor) . 99 2 Moments Musicaux, Op. 94 Impromptus, Opp. 90 & 142 Edited by Murray Baylor SCHUBERT’S PIANO MUSIC Schubert’s music seems to fall between Classical and Foreword Romantic classifications—perhaps between that of Beethoven and Chopin . Although he first became known in Vienna as a composer of lieder, the piano was his instrument, and he wrote some of his finest music for piano solo and piano duet . The kind of instrument he played, however, usually called a fortepiano, was ABOUT THE COMPOSER very different from a modern Steinway . In the Kunsthis- torische Museum in Vienna, there is a well-maintained Of the many famous composers who lived and worked piano that he once owned . Its compass is from the F an in Vienna, Europe’s most musical city, Franz Schubert octave below the bass staff to the F two octaves above was the only one who made his home there from birth the treble—six octaves in all . -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin Minnesota State University - Mankato

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2012 Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Chin, Amy Jun Ming, "Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano" (2012). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 195. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano By Amy J. Chin Program Notes Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music In Piano Performance Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota April 2012 Program Notes for a Graduate Recital in Piano Amy Jun Ming Chin This program notes has been examined and approved by the following members of the program notes committee. Dr. David Viscoli, Advisor Dr.Linda B. Duckett Dr. Karen Boubel Preface The purpose of this paper is to offer a biographical background of the composers, and historical and theoretical analysis of the works performed in my Master’s recital. This will assist the listener to better understand the music performed. Acknowledgements I would like to thank members of my examining committee, Dr. -

HPPAD Advanced Levels A1 A2 Advanced 1

HPPAD Advanced Levels A1 A2 Advanced 1 TECHNIQUE: Scales: All Major and minor scales (in three forms as in Intermediate levels), 4 octaves parallel, HT All Major Scales, 2 octaves Contrary Chromatic Scale 4 octaves Hands Together, starting on any note Chords: I-IV-I-V7-I Cadence in root position and first inversion; bass line, pedal Tonic Triad Inversions blocked and broken, HT (see Intermediate 2) Arpeggios: All Major and Minor scales keys, in root position and 1st inversion, 4 octaves HT Sight Level of Difficulty Time Approximate Keys reading: signature length Intermediate 1 2 3 4 6 Eight Major and minor keys up to three repertoire 4 4 4 8 measures sharps or three flats REPERTOIRE: 2 pieces required; 3 pieces optional; Inclusion of a Sonatina/Sonata movement, is highly recommended; assessment of repertoire performances will be memory neutral Bach, French Suites, easier selections; Two-Part Inventions Mozart, Sonata K.545; Beethoven, Sonata Op. 49 No. 1 Schubert, Scherzo in B Flat Major, selections from Impromptus and Moment Musicaux Schumann, Children’s Sonata op. 118; Grieg, Lyric Pieces, more advanced Chopin, Polonaises in g minor and B Flat Major, Preludes Op. 28, easier selections Kabalevsky, Rondos, Op. 60 (selections); McDowell, Woodland Sketches, Op. 51 Mendelssohn, Songs without Words, Op. 30, selections (N. 3, 6) Schumann, Op. 124, selections (Fantastic Dance) Prokofiev, Music for Children, Op. 65, more difficult selections Other comparable material Advanced 2 TECHNIQUE: Scales: All Majors and minors, 4 octaves -

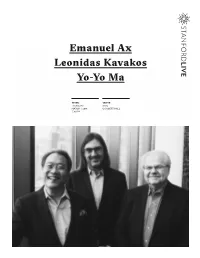

Emanuel Ax, Piano

Sunday, January 22, 2017, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Emanuel Ax, piano PROGRAM Franz SCHUBERT (1797 –1828) Four Impromptus, D. 935 (Op. 142) No. 1 in F minor No. 2 in A-flat Major No. 3 in B-flat Major No. 4 in F minor Frédéric CHOPIN (1810 –1849) Impromptus No. 1 in A-flat Major, Op. 29 No. 2 in F-sharp Major, Op. 36 No. 3 in G-flat Major, Op. 51 Fantaisie-Impromptu in C-sharp minor, Op. 66 INTERMISSION SCHUBERT Klavierstück No. 2 in E-flat Major, D. 946 CHOPIN Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58 Allegro maestoso Scherzo: Molto vivace Largo Finale: Presto non tanto Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ 2016/17 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. Additional support made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Diana Cohen and Bill Falik. Steinway Piano PROGRAM NOTES Four Impromptus, D. 935 (Op. 142) C Major, the last three piano sonatas, the String Franz Schubert Quintet, the two piano trios, the Impromp tus— On January 31, 1827, Franz Schubert turned 30. that he created during the last months of his He had been following a bohemian existence brief life. in Vienna for over a decade, making barely Schubert began his eight pieces titled more than a pittance from the sale and per - Impromptu in the summer and autumn of formance of his works, and living largely off 1827; they were completed by December. He the generosity of his friends, a devoted band of did not invent the title. -

Schubert's Recapitulation Scripts – Part II

CHAPTER 4 CATEGORY 2 RECAPITULATIONS 4.1. Introduction 4.2. Mozart, Monahan, and the Crux 4.3. Beethoven and the Minimally Recomposed Category 2 4.4. Beethoven and Schubert: Labor and Grace 4.5. Repetitions of Single Referential Measures 4.6. A Summary Analysis: The Finale of D. 537 4.7. Conclusion ADD CUT 1. One alteration only, + x 1. One alteration only, - x SIZE a. Minimally different, + 1 a. Minimally different, -1 1. by repetition (at the same pitch 1. deletion of originally repeated level) material 2. by sequence (repetition at a 2. deletion of non-repeated different pitch level) material a. by repetition of multiple referential measures, en bloc (backing up) STRATEGY b. by repetition of a single referential measure (stasis) 3. by composing new material Figure 4.1. Category 2 Strategies. 151 The ways in which thematic and harmonic gestures reappear go well beyond what can be captured by the standard notions of return or recapitulation.1 Like virtually all Western music, the music of the common-practice period is characterized by formal correspondences of various kinds. Such correspondences usually do not form exact symmetries, however, even at the phrase level. This stems partly, no doubt, from distaste for too much repetition and regularity—for predictability, that is, the negative side of the symmetrical coin.2 At this very early date, Riepel could scarcely be expected to realize what he was observing; later, of course, asymmetry would set in on a much greater scale.3 If one does not perceive how a work repeats itself, the work is, almost literally, not perceptible and therefore, at the same time, not intelligible. -

Download Program Notes (PDF)

Emanuel Ax Leonidas Kavakos Yo-Yo Ma WHEN: VENUE: Thursday, BING March 1, 2018 cONcErT haLL 7:30 PM Artists Notes Emanuel ax Leonidas Kavakos yo-yo Ma Brahms took his chamber music Piano Violin Cello seriously and re-energized the medium for the later 19th century, raising it to the highest level of achievement. his Program original plan was to bookend his output with the two versions of the B major Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) piano trio, written a quarter of a century apart—and then retire. But the Trio No. 2 in C Major, Op. 87 (1880–2) expressive musicality of the Meiningen court clarinetist propelled him to add a Allegro moderato coda of four more glorious chamber Andante con moto works as the finale of his creative life. Scherzo: Presto With an overall catalog of 24 widely Finale: Allegro giocoso varied chamber compositions spanning four decades, it’s arguably the piano trios that best marry the medium with Trio No. 3 in C minor, Op. 101 (1886) the message. Before Brahms, Allegro energico Beethoven had found his voice in the string quartet; schubert, for the most Presto non assai part, found his in the string quintet and Andante grazioso schumann his, in the piano quintet. It’s Allegro molto in the piano trio that Brahms finds the most comfortable, natural vehicle for —Intermission— his carefully crafted compositions. Trio No. 1 in B Major, Op. 8 (1853–4, rev. 1889) From the opening, gloriously expansive unison string melody, the Piano Trio No. Allegro con brio 2, in C, Op. -

View Committee

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ “Modern Marvels:” A Pedagogical Guide to Lowell Liebermann’s Album for the Young, Op. 43 A doctoral document submitted to the Graduate Thesis and Research Committee of the College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Adam Clark May, 2008 B.M., University of California, Santa Barbara (2002) M.M., University of Texas, Austin (2004) Project Advisor: Dr. Michelle Conda ABSTRACT Lowell Liebermann’s Album for the Young, Op. 43 is his only venture into the realm of pedagogical composition to date. Written in 1993 and published in 1995, it is a collection of eighteen small pieces for young pianists, progressing in difficulty from elementary (National Music Certificate Program (NMCP) Level 1) through late- intermediate (NMCP Level 8) levels. It contains both traditional and more recent compositional devises as well as numerous technical challenges, such as cross-rhythms, layered textures, and hand crossings. The pieces are intelligent and appealing, and can be a valuable tool -

CHAPTER THREE Schubert's Impromptus

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Rakitzis, Vasileios (2015). Alfred Cortot's response to the music for solo piano of Franz Schubert: a study in performance practice. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16965/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] ALFRED CORTOT’S RESPONSE TO THE MUSIC FOR SOLO PIANO OF FRANZ SCHUBERT: A STUDY IN PERFORMANCE PRACTICE BY VASILEIOS RAKITZIS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts City University London, School of Arts and Social Sciences, Department of Music; and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama London, November, 2015 i ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………..p. ix LIST OF TABLES…………………………………………………………..p.