Journal of Northwest Anthropology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparing a Surface Collection to an Excavated Collection in the Lower Skagit River Delta at 45SK51

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Summer 2017 Comparing a Surface Collection to an Excavated Collection in the Lower Skagit River Delta at 45SK51 Sherri M. Middleton Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Middleton, Sherri M., "Comparing a Surface Collection to an Excavated Collection in the Lower Skagit River Delta at 45SK51" (2017). All Master's Theses. 711. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/711 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARING A SURFACE COLLECTION TO AN EXCAVATED COLLECTION IN THE LOWER SKAGIT RIVER DELTA AT 45SK51 ________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University ________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Cultural and Environmental Resource Management _______________________________________________________________________ by Sherri Michelle Middleton June 2017 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the -

45Th Anniversary Year

VOLUME 45, NO. 1 Spring 2021 Journal of the Douglasia WASHINGTON NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY th To promote the appreciation and 45 conservation of Washington’s native plants Anniversary and their habitats through study, education, Year and advocacy. Spring 2021 • DOUGLASIA Douglasia VOLUME 45, NO. 1 SPRING 2021 journal of the washington native plant society WNPS Arthur R. Kruckberg Fellows* Clay Antieau Lou Messmer** President’s Message: William Barker** Joe Miller** Nelsa Buckingham** Margaret Miller** The View from Here Pamela Camp Mae Morey** Tom Corrigan** Brian O. Mulligan** by Keyna Bugner Melinda Denton** Ruth Peck Ownbey** Lee Ellis Sarah Reichard** Dear WNPS Members, Betty Jo Fitzgerald** Jim Riley** Mary Fries** Gary Smith For those that don’t Amy Jean Gilmartin** Ron Taylor** know me I would like Al Hanners** Richard Tinsley Lynn Hendrix** Ann Weinmann to introduce myself. I Karen Hinman** Fred Weinmann grew up in a small town Marie Hitchman * The WNPS Arthur R. Kruckeberg Fellow Catherine Hovanic in eastern Kansas where is the highest honor given to a member most of my time was Art Kermoade** by our society. This title is given to Don Knoke** those who have made outstanding spent outside explor- Terri Knoke** contributions to the understanding and/ ing tall grass prairie and Arthur R. Kruckeberg** or preservation of Washington’s flora, or woodlands. While I Mike Marsh to the success of WNPS. Joy Mastrogiuseppe ** Deceased love the Midwest, I was ready to venture west Douglasia Staff WNPS Staff for college. I earned Business Manager a Bachelor of Science Acting Editor Walter Fertig Denise Mahnke degree in Wildlife Biol- [email protected] 206-527-3319 [email protected] ogy from Colorado State Layout Editor University, where I really Mark Turner Office and Volunteer Coordinator [email protected] Elizabeth Gage got interested in native [email protected] plants. -

“Viewpoints” on Reconciliation: Indigenous Perspectives for Post-Secondary Education in the Southern Interior of Bc

“VIEWPOINTS” ON RECONCILIATION: INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVES FOR POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION IN THE SOUTHERN INTERIOR OF BC 2020 Project Synopsis By Christopher Horsethief, PhD, Dallas Good Water, MA, Harron Hall, BA, Jessica Morin, MA, Michele Morin, BSW, Roy Pogorzelski, MA September 1, 2020 Research Funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Executive Summary This research project synopsis presents diverse Indigenous community perspectives regarding the efforts needed to enable systemic change toward reconciliation within a public post-secondary educational institution in the Southern Interior of British Columbia. The main research question for this project was “How does a community college respectfully engage in reconciliation through education with the First Nations and Métis communities in the traditional territories in which it operates?” This research was realized by a team of six Indigenous researchers, representing distinct Indigenous groups within the region. It offers Indigenous perspectives, insights, and recommendations that can help guide post-secondary education toward systemic change. This research project was Indigenous led within an Indigenous research paradigm and done in collaboration with multiple communities throughout the Southern Interior region of British Columbia. Keywords: Indigenous-led research, Indigenous research methodologies, truth and reconciliation, Indigenous education, decolonization, systemic change, public post- secondary education in BC, Southern Interior of BC ii Acknowledgements This research was made possible through funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada. The important contributions from the Sinixt, Ktunaxa, Syilx, and Métis Elders, Knowledge Keepers, youth, men, and women within this project are essential to restoring important aspects of education that have been largely omitted from the public education system. -

NATIVE PLANT FIELD GUIDE Revised March 2012

NATIVE PLANT FIELD GUIDE Revised March 2012 Hansen's Northwest Native Plant Database www.nwplants.com Foreword Once upon a time, there was a very kind older gentleman who loved native plants. He lived in the Pacific northwest, so plants from this area were his focus. As a young lad, his grandfather showed him flowers and bushes and trees, the sweet taste of huckleberries and strawberries, the smell of Giant Sequoias, Incense Cedars, Junipers, pines and fir trees. He saw hummingbirds poking Honeysuckles and Columbines. He wandered the woods and discovered trillium. When he grew up, he still loved native plants--they were his passion. He built a garden of natives and then built a nursery so he could grow lots of plants and teach gardeners about them. He knew that alien plants and hybrids did not usually live peacefully with natives. In fact, most of them are fierce enemies, not well behaved, indeed, they crowd out and overtake natives. He wanted to share his information so he built a website. It had a front page, a page of plants on sale, and a page on how to plant natives. But he wanted more, lots more. So he asked for help. I volunteered and he began describing what he wanted his website to do, what it should look like, what it should say. He shared with me his dream of making his website so full of information, so inspiring, so educational that it would be the most important source of native plant lore on the internet, serving the entire world. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1983 Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians Cynthia J. Manning The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Manning, Cynthia J., "Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians" (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5855. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5855 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished m a n u s c r ip t in w h ic h c o p y r ig h t su b s i s t s . Any further r e p r in t in g of it s c o n ten ts must be a ppro ved BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD L ib r a r y Un iv e r s it y of Montana D a te : 1 9 8 3 AN ETHNOHISTORY OF THE KOOTENAI INDIANS By Cynthia J. Manning B.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1978 Presented in partial fu lfillm en t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1983 Approved by: Chair, Board of Examiners Fan, Graduate Sch __________^ ^ c Z 3 ^ ^ 3 Date UMI Number: EP36656 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

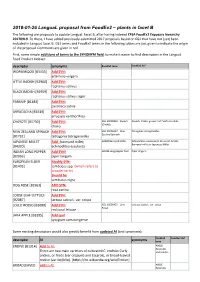

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

Where the Water Meets the Land: Between Culture and History in Upper Skagit Aboriginal Territory

Where the Water Meets the Land: Between Culture and History in Upper Skagit Aboriginal Territory by Molly Sue Malone B.A., Dartmouth College, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Molly Sue Malone, 2013 Abstract Upper Skagit Indian Tribe are a Coast Salish fishing community in western Washington, USA, who face the challenge of remaining culturally distinct while fitting into the socioeconomic expectations of American society, all while asserting their rights to access their aboriginal territory. This dissertation asks a twofold research question: How do Upper Skagit people interact with and experience the aquatic environment of their aboriginal territory, and how do their experiences with colonization and their cultural practices weave together to form a historical consciousness that orients them to their lands and waters and the wider world? Based on data from three methods of inquiry—interviews, participant observation, and archival research—collected over sixteen months of fieldwork on the Upper Skagit reservation in Sedro-Woolley, WA, I answer this question with an ethnography of the interplay between culture, history, and the land and waterscape that comprise Upper Skagit aboriginal territory. This interplay is the process of historical consciousness, which is neither singular nor sedentary, but rather an understanding of a world in flux made up of both conscious and unconscious thoughts that shape behavior. I conclude that the ways in which Upper Skagit people interact with what I call the waterscape of their aboriginal territory is one of their major distinctive features as a group. -

Cultural Resources Assessment for the Mount Vernon Downtown Flood Protection Project Mount Vernon, Skagit County, Washington

CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT FOR THE MOUNT VERNON DOWNTOWN FLOOD PROTECTION PROJECT MOUNT VERNON, SKAGIT COUNTY, WASHINGTON BY MARGARET BERGER AND SUSAN MEDVILLE GLENN D. HARTMANN, PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR PREPARED FOR: PACIFIC INTERNATIONAL ENGINEERING PO BOX 1599 EDMONDS, WA 98020 TECHNICAL REPORT #342 CRC PROJECT #0711I CULTURAL RESOURCE CONSULTANTS, INC. 8001 DAY ROAD WEST, SUITE B BAINBRIDGE ISLAND, WA 98110 FEBRUARY 28, 2008 Executive Summary This report describes a cultural resources assessment for the Mount Vernon Downtown Flood Protection Project, in Mount Vernon, Skagit County, Washington. This assessment was conducted at the request of the City of Mount Vernon. This report is intended to serve as a component of preconstruction environmental review in accordance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), as amended. The project consists of modifications to the existing flood protection system. Project plans include raising the existing earthen levee, installing new levee and floodwall segments in some locations, and a new ring dike around the Mount Vernon Wastewater Treatment Plant. To accommodate levee improvements, seven downtown commercial buildings and a residence will be razed. Assessment methods included a review of relevant background literature and maps, archaeological field reconnaissance survey and testing, and a historic building survey. There are no archaeological sites recorded within the project. Archaeological testing conducted using a backhoe revealed thick alluvial deposits overlain, in places, by fill. No indications of buried archaeological sites were observed, and the project is considered to have a low potential to affect as-yet unknown cultural resources. No further archaeological investigations are recommended prior to commencement of the project. -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

American Rock Garden Society Bulletin

American Rock Garden Society Bulletin DWARF WILLOWS—Reginald Kaye 1 AN ALPINE ADVENTURE IN ICELAND Olajur B. Gudmundsson 6 PLANTS FOR THE WHERRY MEMORIAL GARDEN 10 USEFUL SHRUBS FOR NORTHERN GARDENS G. K. Fender son 11 SYNTHYRIS TODAY—Roy Davidson 14 BOOK REVIEW—Bernard Harkness 25 A SUCCESSFUL COLLECTING TRIP—Tage Lundell 26 OMNIUM-GATHERUM 30 VEGETATIVE PROPAGATION IN SITU—Dr. Daniel C. Weaver 32 ROCK GARDEN FERNS—CETERACH OFFICINARUM James R. Baggett 35 Vol. 30 JANUARY, 1972 No. 1 DIRECTORATE BULLETIN Editor Emeritus DR. EDGAR T. WHERRY, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa. 19104 Editor ALBERT M. SUTTON 9608 26th Ave. N.W., Seattle, Washington 98107 AMERICAN ROCK GARDEN SOCIETY President Emeritus HAROLD EPSTEIN, 5 Forest Court, Larchmont, New York President— BERNARD E. HARKNESS, BOX 264, R.D. #1, Pre-emption Rd., Geneva, N. Y. 14456 Secretary RICHARD W. REDFIELD, BOX 26, Closter, N. J. 07624 Treasurer _ ALEX D. REW, 260 Boulevard, Mountain Lakes, N. J. Vice-Presidents BRIAN O. MULLIGAN DONALD E. HAVENS BOYD KLINE HARRY BUTLER MRS. ARMEN GEVJAN Directors Term Expires 1972 Mrs. Sallie D. Allen Jerome A. Lukins Henry R. Fuller Term Expires 1973 F. Owen Pearce Mrs. L. N. Roberson George Pride Term Expires 1974 Mrs. Herbert Brinckerhoff H. Lincoln Foster Lee Raden Director of Seed Exchange MRS. ARMEN H. GEVJAN 536 Dogwood Place, Newtown Square, Pa. 19073 Director of Slide Collection ELMER C. BALDWIN 400 Tecumseh Road, Syracuse, N. Y. 13224 REGIONAL CHAIRMEN Northwestern MRS. FRANCES KINNE ROBERSON, 1539 NE 103d. Seattle, Wash. 98125 Western F. O. PEARCE, 54 Charles Hill Road, Orinda, Calif. -

Ventura County Plant Species of Local Concern

Checklist of Ventura County Rare Plants (Twenty-second Edition) CNPS, Rare Plant Program David L. Magney Checklist of Ventura County Rare Plants1 By David L. Magney California Native Plant Society, Rare Plant Program, Locally Rare Project Updated 4 January 2017 Ventura County is located in southern California, USA, along the east edge of the Pacific Ocean. The coastal portion occurs along the south and southwestern quarter of the County. Ventura County is bounded by Santa Barbara County on the west, Kern County on the north, Los Angeles County on the east, and the Pacific Ocean generally on the south (Figure 1, General Location Map of Ventura County). Ventura County extends north to 34.9014ºN latitude at the northwest corner of the County. The County extends westward at Rincon Creek to 119.47991ºW longitude, and eastward to 118.63233ºW longitude at the west end of the San Fernando Valley just north of Chatsworth Reservoir. The mainland portion of the County reaches southward to 34.04567ºN latitude between Solromar and Sequit Point west of Malibu. When including Anacapa and San Nicolas Islands, the southernmost extent of the County occurs at 33.21ºN latitude and the westernmost extent at 119.58ºW longitude, on the south side and west sides of San Nicolas Island, respectively. Ventura County occupies 480,996 hectares [ha] (1,188,562 acres [ac]) or 4,810 square kilometers [sq. km] (1,857 sq. miles [mi]), which includes Anacapa and San Nicolas Islands. The mainland portion of the county is 474,852 ha (1,173,380 ac), or 4,748 sq.