2021 Ohio Sunshine Laws Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Closed, Vol. 27 Ebook Free Download

CASE CLOSED, VOL. 27 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 184 pages | 29 Oct 2009 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421516790 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed, Vol. 27 PDF Book January 20, [22] Ai Haibara. Views Read Edit View history. Until Jimmy can find a cure for his miniature malady, he takes on the pseudonym Conan Edogawa and continues to solve all the cases that come his way. The Junior Detective League and Dr. Retrieved November 13, January 17, [8]. Product Details. They must solve the mystery of the manor before they are all killed off or kill each other. They talk about how Shinichi's absence has been filled with Dr. Chicago 7. April 10, [18] Rachel calls Richard to get involved. Rachel thinks it could be the ghost of the woman's clock tower mechanic who died four years prior. Conan's deductions impress Jodie who looks at him with great interest. Categories : Case Closed chapter lists. And they could have thought Shimizu was proposing a cigarette to Bito. An unknown person steals the police's investigation records relating to Richard Moore, and Conan is worried it could be the Black Organization. The Junior Detectives find the missing boy and reconstruct the diary pages revealing the kidnapping motive and what happened to the kidnapper. The Junior Detectives meet an elderly man who seems to have a lot on his schedule, but is actually planning on committing suicide. Magic Kaito Episodes. Anime News Network. Later, a kid who is known to be an obsessive liar tells the Detective Boys his home has been invaded but is taken away by his parents. -

Hamilton County Auditors Through History

Hamilton County Auditors through History The State Legislature created the office of County Auditor during the 1820-21 legislative session. It was an annually elected position until 1824, when it became a 2-year term. It became a 4-year term in 1924. There have been 30 elected Auditors since the first elected Auditor and two appointed Auditors. John T Jones John S Wallace Hugh McDougal John S Thorp A W Armstrong Frank Linck (Appointed) J Dan Jones Howard Matthews William P Ward John E Bell S W Seibern August Willich George S LaRue W M Yeatman Joseph B Humphreys William S Cappeller J W Brewster Fred Raine John Hagerty Eugene L Lewis Charles C. Richardson Robert E Edmondson Fred Bader Peter William Durr Edward S Beaman William F Hess Robert Heuck George Guckenberger Fred J Morr Joseph L Decourcy Jr Michael Maloney (Appointed) Dusty Rhodes John T. Jones was originally from the Pennsylvania Quaker community. He was Auditor in 1825, serving as the First County Auditor. He was also Clerk for the City of Cincinnati in 1829-1831. In 1831, he moved to Illinois and was one of the most instrumental leaders of the Church of Christ. A published biographical sketch says, “His business capacity, habits of industry and acknowledged integrity of character, gave him many positions of honor and trust”. John S. Wallace was described as “one of the earliest settlers of Cincinnati and a resident here until his death”. He was Auditor from 1829-1836. He also served as a Commissioner and Sheriff along with such famous early community leaders as William Henry Harrison, Martin Baum, William Lytle, and John S Gano. -

Bylaws of the Democratic Party of the State of Washington

Bylaws of the Democratic Party of the State of Washington As amended by the Washington State Democratic Convention on June 13th, 2020 Article I State Democratic Convention The State Convention of the Democratic Party is the highest authority of the Democratic Party of the State of Washington, subject to the provisions of the Charter of the Democratic Party of the State of Washington. The Convention shall be called by the Washington State Democratic Central Committee pursuant to Articles V and VI of the State Charter. Article II Washington State Democratic Central Committee A. Purpose and Powers 1. The Washington State Democratic Central Committee, also known as the state central committee ("SCC'), is the governing body of the Democratic Party of the State of Washington as authorized by the Democratic State Convention and the Charter of the Democratic Party of the State of Washington. 2. The SCC shall have all powers and carry out all duties delegated to it by the Convention under the Charter. The SCC is the sole Party organization authorized to collect and disburse funds in the name of the Democratic Party of the State of Washington. The SCC provides the funds, staff and other assistance necessary for the operations of its committees. B. Membership 1. The SCC shall consist of the state committeewoman and the state committeeman elected from each legislative district and from each county of the State of Washington, without regard to whether each is a precinct committee officer, in compliance with Article III B of the Charter. 2. Members shall be elected for two-year terms and shall serve until their successors have been elected. -

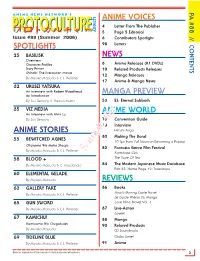

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

APPENDIX 1A APPENDIX a UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the SIXTH CIRCUIT ———— No

APPENDIX 1a APPENDIX A UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT ———— No. 19-3196 ———— WILLIAM T. SCHMITT; CHAD THOMPSON; DEBBIE BLEWITT, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. FRANK LAROSE, Ohio Secretary of State, Defendant-Appellant. ———— Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio at Columbus No. 2:18-cv-00966— Edmund A. Sargus, Jr., Chief District Judge. ———— Argued: June 26, 2019 Decided and Filed: August 7, 2019 ———— Before: CLAY, WHITE, and BUSH, Circuit Judges. ———— COUNSEL ARGUED: Benjamin M. Flowers, OFFICE OF THE OHIO ATTORNEY GENERAL, Columbus, Ohio, for Appellant. Mark R. Brown, CAPITAL UNIVERSITY LAW SCHOOL, Columbus, Ohio, for Appellees. ON 2a BRIEF: Benjamin M. Flowers, Michael J. Hendershot, Stephen P. Carney, OFFICE OF THE OHIO ATTOR- NEY GENERAL, Columbus, Ohio, for Appellant. Mark R. Brown, CAPITAL UNIVERSITY LAW SCHOOL, Columbus, Ohio, Mark G. Kafantaris, Columbus, Ohio, for Appellees. WHITE, J., delivered the opinion of the court in which CLAY, J., joined, and BUSH, J., joined in part. BUSH, J. (pp. 15–26), delivered a separate opinion concurring in part and in the judgment. OPINION HELENE N. WHITE, Circuit Judge. Plaintiffs William T. Schmitt and Chad Thompson submitted proposed ballot initiatives to the Portage County Board of Elections that would effectively decriminal- ize marijuana possession in the Ohio villages of Garrettsville and Windham. The Board declined to certify the proposed initiatives after concluding that the initiatives fell outside the scope of the municipali- ties’ legislative authority. Plaintiffs then brought this action asserting that the statutes governing Ohio’s municipal ballot-initiative process impose a prior restraint on their political speech, violating their rights under the First and Fourteenth Amendments. -

Amended Complaint

Case 3:21-cv-00065 Document 71 Filed on 06/01/21 in TXSD Page 1 of 59 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS GALVESTON DIVISION STATE OF TEXAS; STATE OF MONTANA; STATE OF ALABAMA; STATE OF ALASKA; STATE OF ARIZONA; STATE OF ARKANSAS; STATE OF FLORIDA; STATE OF GEORGIA; STATE OF KANSAS; COMMONWEATH OF KENTUCKY; STATE OF INDIANA; STATE OF LOUISIANA; STATE OF Civ. Action No. 3:21-cv-00065 MISSISSIPPI; STATE OF MISSOURI; STATE OF NEBRASKA; STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA; STATE OF OHIO; STATE OF OKLAHOMA; STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA; STATE OF SOUTH DAKOTA; STATE OF UTAH; STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA; and STATE OF WYOMING, Plaintiffs, v. JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., in his official capacity as President of the United States; ANTONY J. BLINKEN, in his official capacity as Secretary of the Department of State; MERRICK B. GARLAND, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the United States; Case 3:21-cv-00065 Document 71 Filed on 06/01/21 in TXSD Page 2 of 59 ALEJANDRO MAYORKAS, in his official capacity as Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security; DEB HAALAND, in her official capacity as Secretary of the Interior; JENNIFER GRANHOLM, in her official capacity as Secretary of the Department of Energy; MICHAEL S. REGAN, in his official capacity as Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency; THOMAS J. VILSACK, in his official capacity as the Secretary of Agriculture; PETE BUTTIGIEG, in his official capacity as Secretary of Transportation; SCOTT A. SPELLMON, in his official capacity as Commanding General of the U.S. -

On the Job Summer/Fall 2020 3 Q a Q A

COVER STORY THE TIME TO BUILD, NOT TEAR DOWN Summer turmoil opens doors for boosting trust, proving value of police hen a cop puts on the badge, it is an act of courage – an act that accepts the risks of the job, that promises Wto place the good of the community above his or her own welfare. To support the defunding of local law enforcement, people must choose to ignore that basic fact and believe several things that are simply not true: that officers regularly shoot unarmed people, wantonly discriminate and gas protesters — and that they delight in doing so. “I’ve known many more officers and deputies who have arrested child abusers, murderers and traffickers than cops who have ever had to fire their weapon in the line of duty,” said Attorney General Dave Yost, who readily acknowledges that “defund” campaigns tick him off. Continued on Page 2 INSIDE » Former officers share why they jumped into politics» Case of missing teen complicated from start to finish 1 ON THE JOB COVER STORY COVER STORY for barbers, construction-industry contractors, on casino proceeds, and empty casinos meant a • Driving, traffic stops and related courses: As we talk about police reforms, it’s important to recognize that we don’t have a police lawyers, medical workers of all kinds, social payment 13 times smaller than usual. OPOTA has the state’s only large-scale driving problem; we have a societal problem with a law enforcement component. workers and teachers. But Yost had started looking at OPOTA’s costs track for law enforcement, and the popular The plan would essentially add an oversight and and benefits even before the pandemic. -

The Judicial Appointment Process: an Appeal for Moderation and Self-Restraint

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 7 Issue 1 Volume 7, Fall 1991, Issue 1 Article 15 The Judicial Appointment Process: An Appeal for Moderation and Self-Restraint Joerg W. Knipprath Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JUDICIAL APPOINTMENT PROCESS: AN APPEAL FOR MODERATION AND SELF-RESTRAINT JOERG W. KNIPPRATH* The original hearings on the nomination of Clarence Thomas brought much political posturing and theatrical grilling of the nominee. That much was expected in light of the Bork, Kennedy, and Souter hearings. As on those prior occasions, the Senators elected to define their constitutional "consent" function by prob- ing, by turns gingerly and testily, the nominee's political views. As then became painfully obvious, from October 11 th to the 13th the nomination hearing self-destructed. The scripted was out; the unexpected was in. Senators, staff, and media descended into a miasma of sexual allegations, hard-ball politics, betrayed confidences, and half-baked psychoanalysis. By the time the wal- lowing ceased, the substance of the charges had become less the issue than "the process" itself and the participants therein. Anita Hill's charges of sexual harassment against Clarence Thomas were a political neutron bomb. The edifice-the confir- mation process-still stands. -

The Senate in Transition Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Nuclear Option1

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYL\19-4\NYL402.txt unknown Seq: 1 3-JAN-17 6:55 THE SENATE IN TRANSITION OR HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE NUCLEAR OPTION1 William G. Dauster* The right of United States Senators to debate without limit—and thus to filibuster—has characterized much of the Senate’s history. The Reid Pre- cedent, Majority Leader Harry Reid’s November 21, 2013, change to a sim- ple majority to confirm nominations—sometimes called the “nuclear option”—dramatically altered that right. This article considers the Senate’s right to debate, Senators’ increasing abuse of the filibuster, how Senator Reid executed his change, and possible expansions of the Reid Precedent. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 632 R I. THE NATURE OF THE SENATE ........................ 633 R II. THE FOUNDERS’ SENATE ............................. 637 R III. THE CLOTURE RULE ................................. 639 R IV. FILIBUSTER ABUSE .................................. 641 R V. THE REID PRECEDENT ............................... 645 R VI. CHANGING PROCEDURE THROUGH PRECEDENT ......... 649 R VII. THE CONSTITUTIONAL OPTION ........................ 656 R VIII. POSSIBLE REACTIONS TO THE REID PRECEDENT ........ 658 R A. Republican Reaction ............................ 659 R B. Legislation ...................................... 661 R C. Supreme Court Nominations ..................... 670 R D. Discharging Committees of Nominations ......... 672 R E. Overruling Home-State Senators ................. 674 R F. Overruling the Minority Leader .................. 677 R G. Time To Debate ................................ 680 R CONCLUSION................................................ 680 R * Former Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy for U.S. Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid. The author has worked on U.S. Senate and White House staffs since 1986, including as Staff Director or Deputy Staff Director for the Committees on the Budget, Labor and Human Resources, and Finance. -

Conference Resolution

CONFERENCE RESOLUTION Resolved, that the following shall be the rules of the House Republican Conference for the 115th Congress: Rule 1—Conference Membership (a) Inclusion.—All Republican Members of the House of Representatives (including Delegates and the Resident Commissioner) and other Members of the House as determined by the Republican Conference of the House of Representatives (“the Conference”) shall be Members of the Conference. (b) Expulsion.—A ⅔ vote of the entire membership shall be necessary to expel a Member of the Conference. Proceedings for expulsion shall follow the rules of the House of Representatives, as nearly as practicable. Rule 2—Republican Leadership (a) Elected Leadership.—The Elected Republican Leaders of the House of Representatives are— (1) the Speaker; (2) the Republican Leader; (3) the Republican Whip; (4) the Chair of the Republican Conference; (5) the Chair of the National Republican Congressional Committee; (6) the Chair of the Committee on Policy; (7) the Vice-Chair of the Republican Conference; and, (8) the Secretary of the Republican Conference. (b) Designated Leadership.—The designated Republican Leaders of the House of Representatives are— (1) the Chair of the House Committee on Rules; (2) the Chair of the House Committee on Ways and Means; (3) the Chair of the House Committee on Appropriations; (4) the Chair of the House Committee on the Budget; (5) the Chair of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce; (6) the Chief Deputy Whip; (7) one member of the sophomore class elected by the sophomore class; and, (8) one member of the freshman class elected by the freshman class. (c) Leadership Issues.—The Republican Leader may designate certain issues as “Leadership Issues.” Those issues will require early and ongoing cooperation between the relevant committees and the Leadership as those issues evolve. -

In the Common Pleas Court Delaware County, Ohio Civil Division

IN THE COMMON PLEAS COURT DELAWARE COUNTY, OHIO CIVIL DIVISION STATE OF OHIO ex rel. DAVE YOST, OHIO ATTORNEY GENERAL, Case No. 21 CV H________________ 30 East Broad St. Columbus, OH 43215 Plaintiff, JUDGE ___________________ v. GOOGLE LLC 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway COMPLAINT FOR Mountain View, CA 94043 DECLARATORY JUDGMENT AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Also Serve: Google LLC c/o Corporation Service Co. 50 W. Broad St., Ste. 1330 Columbus OH 43215 Defendant. Plaintiff, the State of Ohio, by and through its Attorney General, Dave Yost, (hereinafter “Ohio” or “the State”), upon personal knowledge as to its own acts and beliefs, and upon information and belief as to all matters based upon the investigation by counsel, brings this action seeking declaratory and injunctive relief against Google LLC (“Google” or “Defendant”), alleges as follows: I. INTRODUCTION The vast majority of Ohioans use the internet. And nearly all of those who do use Google Search. Google is so ubiquitous that its name has become a verb. A person does not have to sign a contract, buy a specific device, or pay a fee to use Good Search. Google provides its CLERK OF COURTS - DELAWARE COUNTY, OH - COMMON PLEAS COURT 21 CV H 06 0274 - SCHUCK, JAMES P. FILED: 06/08/2021 09:05 AM search services indiscriminately to the public. To use Google Search, all you have to do is type, click and wait. Primarily, users seek “organic search results”, which, per Google’s website, “[a] free listing in Google Search that appears because it's relevant to someone’s search terms.” In lieu of charging a fee, Google collects user data, which it monetizes in various ways—primarily via selling targeted advertisements. -

August 25, 2021 the Honorable Merrick Garland Attorney General

MARK BRNOVICH DAVE YOST ARIZONA ATTORNEY GENERAL OHIO ATTORNEY GENERAL August 25, 2021 The Honorable Merrick Garland Attorney General 950 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20530-0001 Re: Constitutionality of Illegal Reentry Criminal Statute, 8 U.S.C. § 1326 Dear Attorney General Garland, We, the undersigned attorneys general, write as chief legal officers of our States to inquire about your intent to appeal the decision in United States v. Carrillo-Lopez, No. 3:20-cr- 00026-MMD-WGC, ECF. 60 (D. Nev. Aug. 18, 2021). As you know, in that decision, Chief Judge Du found unconstitutional 8 U.S.C. § 1326, the statute that criminalizes the illegal reentry of previously removed aliens. We appreciate that you recently filed a notice of appeal, preserving your ability to defend the law on appeal. We now urge you to follow through by defending the law before the Ninth Circuit and (if necessary) the Supreme Court. We ask that you confirm expeditiously DOJ’s intent to do so. Alternatively, if you do not intend to seek reversal of that decision and instead decide to cease prosecutions for illegal reentry in some or all of the country, we ask that you let us know, in writing, so that the undersigned can take appropriate action. Section 1326, as part of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, is unremarkable in that it requires all aliens—no matter their race or country of origin—to enter the country lawfully. In finding the law racially discriminatory against “Latinx persons,” Chief Judge Du made some truly astounding claims, especially considering that, under the Immigration and Nationality Act, Mexico has more legal permanent residents in the United States, by far, than any other country.1 Chief Judge Du determined that, because most illegal reentrants at the border are from Mexico, the law has an impermissible “disparate impact” on Mexicans.