Reference Manual 45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S T a T E O F N E W Y O R K 3695--A 2009-2010

S T A T E O F N E W Y O R K ________________________________________________________________________ 3695--A 2009-2010 Regular Sessions I N A S S E M B L Y January 28, 2009 ___________ Introduced by M. of A. ENGLEBRIGHT -- Multi-Sponsored by -- M. of A. KOON, McENENY -- read once and referred to the Committee on Tourism, Arts and Sports Development -- recommitted to the Committee on Tour- ism, Arts and Sports Development in accordance with Assembly Rule 3, sec. 2 -- committee discharged, bill amended, ordered reprinted as amended and recommitted to said committee AN ACT to amend the parks, recreation and historic preservation law, in relation to the protection and management of the state park system THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, REPRESENTED IN SENATE AND ASSEM- BLY, DO ENACT AS FOLLOWS: 1 Section 1. Legislative findings and purpose. The legislature finds the 2 New York state parks, and natural and cultural lands under state manage- 3 ment which began with the Niagara Reservation in 1885 embrace unique, 4 superlative and significant resources. They constitute a major source of 5 pride, inspiration and enjoyment of the people of the state, and have 6 gained international recognition and acclaim. 7 Establishment of the State Council of Parks by the legislature in 1924 8 was an act that created the first unified state parks system in the 9 country. By this act and other means the legislature and the people of 10 the state have repeatedly expressed their desire that the natural and 11 cultural state park resources of the state be accorded the highest 12 degree of protection. -

Parks Attendance Summary

Parks Attendance 8/29/2012 3:37:13 PM Summary Search Criteria: Region: -All- From Date: 1/1/2011 To Date: 8/28/2011 Group By: None Park Name: -All- IsStatistical: No Category: -All- Reg Costcenter Attendance -ALL- Allegany Quaker Area 423,970 Allegany Red House Area 500,778 Lake Erie St Pk 75,666 Long Point Marina 56,030 Midway State Park 82,880 Battle Isl Golf Course 22,209 Betty And Wilbur Davis State Park 12,756 Bowman Lake St Pk 40,515 Canadarago Boat Lnch 18,903 Chenango Valley St Pk 124,247 Chittenango Fls St Pk 30,551 Clark Reservation 34,530 Delta Lake St Pk 158,574 Fort Ontario 96,717 Gilbert Lake St Pk 79,082 Glimmerglass State Park 98,066 Green Lakes State Park 633,669 1 of 8 Herkimer Home 10,744 Lorenzo 25,265 Mexico Point Boat Launch 14,201 Old Erie Canal 16,916 Oquaga State Park 24,292 Oriskany Battlefield 3,446 Pixley Falls State Park 24,124 Sandy Island Beach 33,793 Selkirk Shores 53,235 Steuben Memorial 438 Verona Beach State Park 153,719 Allan Treman Marina 115,237 Buttermilk Falls St Pk 116,327 Canadaigua Btlau Ontrio 37,866 Cayuga Lake St Pk 93,276 Chimney Bluffs 86,443 Deans Cove Boat Launch 11,572 Fair Haven St Pk 230,052 Fillmore Glen St Pk 92,150 Ganondagan 22,339 H H Spencer 24,907 Honeoye Bt Lau 26,879 Indian Hills Golf Course 19,908 Keuka Lake St Pk 69,388 Lodi Point Marina/Boat 23,237 Long Point St Pk 33,257 Newtown Battlefield 17,427 Robert H Treman St Pk 158,724 Sampson St Pk 111,203 Seneca Lake St Pk 116,517 2 of 8 Soaring Eagles Golf Course 18,511 Stony Brook St Pk 118,064 Taughannock Falls St Pk 328,376 Watkins Glen St Pk 381,218 Braddock Bay 28,247 Conesus Lake Boat Launch 18,912 Darien Lakes State Park 52,750 Durand Eastman 18,704 Genesee Valley Greenway 21,022 Hamlin Beach State Park 221,996 Irondquoit Bay Boat Lnch 27,035 Lakeside Beach St Pk 50,228 Letchworth State Park 407,606 Oak Orchard Boat Launch 4,954 Rattlesnake Point 1,699 Silver Lake 17,790 Bayard C. -

Historical Pathway Through the 59Th Senate District

Your Historical Pathway Through the 59th Senate District New York State Senator Patrick M. Gallivan Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railway Historic Pathways Of the 59th Senate District estern New York is rich in historical tradition Wand you’re invited to learn about our area’s past, present, and future. From the natural beauty of our State Parks to the architecture created by early settlers, there is something to explore and discover around every corner. Learn about the local people who made history, including former President Millard Fillmore, by touring their homes and where they worked. So what are you waiting for? Come explore our rich local history and experience for yourself the many great sites in the 59th Senate District. Millard Fillmore House Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railroad Station Roycroft Campus Millard Fillmore House ERIE COUNTY Springville Station D, F, H, K, L, V, W, X, AA, BB, CC, DD, EE, GG, HH, PP, QQ O, Q T, Z, FF, LL ERIE R, U COUNTY Y J JJ S, MM C, RR II, KK E, G, M, N, P NN, OO A. Aurora Historical Museum D. Bruce-Briggs Brick Block ERIE 300 Gleed Avenue 5483 Broadway East Aurora, NY 14052 Lancaster, NY 14086 (716) 652-4735 Bruce-Briggs Brick Block is a historic COUNTY The Aurora Historical Society was founded rowhouse block which incorporates both Greek Revival and Italianate style decorative A Aurora Historical Museum in 1951 by a group who recognized the B Baker Memorial Methodist importance of preserving our past for the details and is considered to be a mid-19th Episcopal Church enlightenment and enrichment of future century brick structure unique in WNY. -

2015 State Council of Parks Annual Report

2015 ANNUAL REPORT New York State Council of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation Seneca Art & Culture Center at Ganondagan State Historic Site Franklin D. Roosevelt State Park Governor Andrew M. Cuomo at Minnewaska State Park, site of new Gateway to the park. Letchworth State Park Nature Center groundbreaking Table of Contents Letter from the Chair 1 Priorities for 2016 5 NYS Parks and Historic Sites Overview 7 State Council of Parks Members 9 2016-17 FY Budget Recommendations 11 Partners & Programs 12 Annual Highlights 14 State Board for Historic Preservation 20 Division of Law Enforcement 22 Statewide Stewardship Initiatives 23 Friends Groups 25 Taughannock Falls State Park Table of Contents ANDREW M. CUOMO ROSE HARVEY LUCY R. WALETZKY, M.D. Governor Commissioner State Council Chair The Honorable Andrew M. Cuomo Governor Executive Chamber February 2016 Albany, NY 12224 Dear Governor Cuomo, The State Council of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation is pleased to submit its 2015 Annual Report. This report highlights the State Council of Parks and the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation’s achievements during 2015, and sets forth recommendations for the coming year. First, we continue to be enormously inspired by your unprecedented capital investment in New York state parks, which has resulted in a renaissance of the system. With a total of $521 million invested in capital projects over the last four years, we are restoring public amenities, fixing failing infrastructure, creating new trails, and bringing our state’s flagship parks back to life. New Yorkers and tourists are rediscovering state parks, and the agency continues to plan for the future based on your commitment to provide a total of $900 million in capital funds as part of the NY Parks 2020 initiative announced in your 2015 Opportunity Agenda. -

Appendices Section

APPENDIX 1. A Selection of Biodiversity Conservation Agencies & Programs A variety of state agencies and programs, in addition to the NY Natural Heritage Program, partner with OPRHP on biodiversity conservation and planning. This appendix also describes a variety of statewide and regional biodiversity conservation efforts that complement OPRHP’s work. NYS BIODIVERSITY RESEARCH INSTITUTE The New York State Biodiversity Research Institute is a state-chartered organization based in the New York State Museum who promotes the understanding and conservation of New York’s biological diversity. They administer a broad range of research, education, and information transfer programs, and oversee a competitive grants program for projects that further biodiversity stewardship and research. In 1996, the Biodiversity Research Institute approved funding for the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation to undertake an ambitious inventory of its lands for rare species, rare natural communities, and the state’s best examples of common communities. The majority of inventory in state parks occurred over a five-year period, beginning in 1998 and concluding in the spring of 2003. Funding was also approved for a sixth year, which included all newly acquired state parks and several state parks that required additional attention beyond the initial inventory. Telephone: (518) 486-4845 Website: www.nysm.nysed.gov/bri/ NYS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION The Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) biodiversity conservation efforts are handled by a variety of offices with the department. Of particular note for this project are the NY Natural Heritage Program, Endangered Species Unit, and Nongame Unit (all of which are in the Division of Fish, Wildlife, & Marine Resources), and the Division of Lands & Forests. -

Final Environmental Assessment for Conversion of a Portion of Fort Niagara State Park

Final Environmental Assessment for Conversion of a Portion of Fort Niagara State Park For adaptive re-use of Historic Buildings And acquisition of replacement lands at Bear Mountain State Park Prepared by: Karen Terbush, Environmental Analyst 2 Edwina Belding, Environmental Analyst 2 NYS Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Environmental Management Bureau Albany NY 12238 (518) 474-0409 March 2013 - 1 - Table of Contents Page Chapter 1 - Purpose, Need, Background 4 Chapter 2 – Description of Alternatives 7 2.1 Proposed Action 7 Fort Niagara State Park 7 Substitute Parcel-Bear Mountain State Park 9 Relationship to SCORP and Description of Reasonably 11 Equivalent Usefulness 2.2 No Action 12 Chapter 3 – Affected Environment 12 3.1 Fort Niagara State Park 12 3.2 Substitute/Replacement Land-Bear Mountain State Park 23 Chapter 4 – Environmental Impacts and Mitigation 4.1 Fort Niagara State Park 27 4.2 Substitute/Replacement Land-Bear Mountain State Park 30 Chapter 5 – Consultation and Coordination 5.1 Previous Environmental Review and Public Involvement 31 5.2 Additional Public Involvement 32 5.3 Consultation 32 5.4 Coastal Review 32 References 33 Appendices ~ 2 ~ List of Tables. Page Table 1. Description of previous LWCF funded projects at Fort Niagara SP 5 Table 2. History of underground fuel storage tanks in the project area and 22 their removal List of Figures. Page Figure 1. Existing 6(f) boundary Fort Niagara State Park 6 Figure 2. Map showing relationship between Fort Niagara State Park 7 and replacement parcel at Bear Mountain State Park Figure 3. Fort Niagara State Park and proposed conversion area 8 Figure 4. -

Snap That Sign 2021: List of Pomeroy Foundation Markers & Plaques

Snap That Sign 2021: List of Pomeroy Foundation Markers & Plaques How to use this document: • An “X” in the Close Up or Landscape columns means we need a picture of the marker in that style of photo. If the cell is blank, then we don’t need a photo for that category. • Key column codes represent marker program names as follows: NYS = New York State Historic Marker Grant Program L&L = Legends & Lore Marker Grant Program NR = National Register Signage Grant Program L&L marker NYS marker NR marker NR plaque • For GPS coordinates of any of the markers or plaques listed, please visit our interactive marker map: https://www.wgpfoundation.org/history/map/ Need Need Approved Inscription Address County Key Close Up Landscape PALATINE TRAIL ROAD USED FOR TRAVEL WEST TO SCHOHARIE VALLEY. North side of Knox Gallupville Road, AS EARLY AS 1767, THE Albany X NYS Knox TOWN OF KNOX BEGAN TO GROW AROUND THIS PATH. WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2015 PAPER MILLS 1818 EPHRAIM ANDREWS ACQUIRES CLOTH DRESSING AND County Route 111 and Water Board Rdl, WOOL CARDING MILLS. BY 1850 Albany X NYS Coeymans JOHN E. ANDREWS ESTABLISHES A STRAW PAPER MAKING MILL WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2014 FIRST CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH OF 405 Quail Street, Albany Albany x x NR ALBANY RAPP ROAD COMMUNITY HISTORIC DISTRICT 28 Rapp Road, Albany Albany x NR CUBA CEMETERY Medbury Ave, Cuba Allegany x x NR CANASERAGA FOUR CORNERS HISTORIC 67 Main St., Canaseraga Allegany x NR DISTRICT A HAIRY LEGEND FIRST SIGHTED AUG 18, 1926 HAIRY WOMEN OF KLIPNOCKY, ONCE YOUNG GIRLS, INHABIT 1329 County Route 13C, Canaseraga Allegany x L&L THIS FOREST, WAITING FOR THEIR PARENTS' RETURN. -

2017 Tour Brochure

20172017 TourTour BrochureBrochure www.goswarthout.com 115 Graham Road Ithaca, NY 14850 Telephone: 607.257.2277 Toll Free: 800.772.7267 Fax: 607.257.0218 Please note that all of our Tours will involve a certain amount of walking. If you have special needs please contact our office prior to making reservations. Table of Contents Calendar 2017 3 Monthly Tours 4 New York City: A Day On Your Own 5 Turning Stone Resort & Casino 6 One Day Tours 7 Mystery Trip 8 Jonah: Sight & Sound Theater 9 Erie Canal/Sonnenburg Gardens 10 Statue of Liberty 11 Turning Stone/Yellowbrick Road 12 Intrepid/Circle Line Cruise 13 Mets vs. LA Dodgers 14 Strong Museum/ George Eastman House 15 Yankees vs. Boston Red Sox 16 Above & Beyond the Canyon 17 Honsdale - Fire & Ice RR Tour 18 Letchworth State Park 19 Little League/Reptileland 20 QVC 21 Radio City Music Hall 22 Multi Day Tours 23 Philadelphia Flower Show/Longwood Gardens 24 Atlantic City Resorts 25 Myrtle Beach 26-27 Cape Cod 28 2 3 Monthly Tours 4 NEWNEW YORKYORK CITYCITY Price $64 The THIRD Saturday Monthly MAR 18 we travel to the Big Apple APR 15 *(Additional December Trips) MAY 20 ~Day on your Own~ JUN 17 One rest stop on the way to NYC JUL 15 so please feel free to bring refreshments (no glass please). AUG 19 Your escort will assist you, SEP 16 answer any questions you may OCT 21 have, and also provide you with a NOV 18 map. DEC 2 Drop off at: DEC 9 Bryant Park (42nd St & 6th Ave) Pick up at: DEC 13 Bryant Park 8pm SHARP DEC 16 Departs: Arrives: 5:45am Ithaca–Behind the Ramada Inn 11:15pm Binghamton–Cracker Barrel 6:00am Ithaca–Green St. -

Ticks on the Trail

President’s Message Pat Monahan pring is in the air and with it comes a new hiking season Maintenance. Add Director of Crews and Construction and for many who do not hike in winter. Leaving behind the Director of Trail Inventory and Mapping. All of the duties S snow shoes and crampons, I look forward to the woodlands will be described in the Guide to Responsibilities which coming alive for another hike along our wilderness foot path and defines the responsibilities of positions in the FLTC. More to sharing in the sights and sounds of spring. How many of us information will follow under separate cover in preparation look forward to the trillium, mayapple, and, yes, even the skunk for the annual meeting. cabbage as welcome signs to get up off the couch and get back on As we begin 2010, I will again ask you to consider how you can the trail in the woods? Now is the time. While many of us have support the FLTC. During the month of March, the FLTC will been hibernating over the last few months, the FLTC has been hold its annual membership drive. This is a tough economy planning and preparing for 2010. Let me highlight just a few which requires tough decisions by each of us as we consider areas for you. where to spend or invest our money. I believe it is a great value. The FLTC and the North Country Trail Association (NCTA) We have not increased our dues for 2010. The FLTC has have reached a formal agreement to work together as shown a steady (5%) increase in membership over the last partners for a high quality hiking experience on the shared several years, unlike similar organizations. -

Autumn in Finger Lakes 2019.Pdf

AUTUMN IN FINGER LAKES SEPT 30 - OCT 3, 2019 Per person Double occupancy $1,195.00 Includes All Taxes Single: $1,545.00 Triple: $1,170.00 Quad: $1,150.00 Your Getaway Includes: Deluxe Highway Motorcoach Breakfast Daily 3 Nights’ Accommodation Finger Lakes Winery Steamboat Luncheon Cruise Two Dinners Belhurst Castle Wine Tour & Dinner Letchworth State Park Baggage Handling Admission to Willard Memorial Chapel Corning Glass Museum Sonnenberg Gardens Services of a Lakeshore Tours – Tour Director 258 King Street East Bowmanville, Ontario L1C 0N3 Phone – (905) 623-1511 Toll Free – (800) 387-5914 Email: [email protected] Ontario Registration Retail – 50017545 Website: www.lakeshoretours.ca Wholesale - 50017546 Autumn in Finger Lakes SEPT 30 - OCT 3, 2019 PROPOSED ITINERARY Mon. Sept. 30 - Early morning departure Duty Free Shopping Letchworth State Park Tour (Grand Canyon of the East) Included Dinner at Glen Iris Inn Overnight at Hampton Inn, Geneva, NY (Three Nights) Tues. Oct. 1 - Hampton Inn Hot Breakfast Tour of Finger Lakes Region Visit Willard Memorial Tiffany Chapel Lunch on Own and Shopping Visit Strawberry Fields Hydroponic Farm Winery Tour and Tasting Included Dinner Wed. Oct. 2 - Hampton Inn Hot Breakfast Visit Sonnenberg Gardens & Mansion State Historic Park Steamboat Scenic Luncheon Cruise Dinner at Belhurst Castle with Wine Tasting Thurs. Oct. 3 - Hampton Inn Hot Breakfast Depart for Corning, NY Visit Corning Glass Museum Included Lunch at a Local Restaurant - Duty Free Shopping Arrive Home Early Evening 258 King Street East Bowmanville, Ontario L1C 0N3 Phone – (905) 623-1511 Toll Free – (800) 387-5914 Email: [email protected] Ontario Registration Retail – 50017545 Website: www.lakeshoretours.ca Wholesale - 50017546 . -

Letchworth State Park Wyoming County, NY Home of the Grand Canyon of the East

2019 Official Visitor Guide Letchworth State Park Wyoming County, NY Home of the Grand Canyon of the East Your adventure GoWyomingCountyNY.com awaits ... 1-800-839-3919 WELCOME TO WYOMING COUNTY Montreal Ottawa Yours to Explore LETCHWORTH STATE PARK, PHOTO CREDIT BREEZE PHOTOGRAPHY 401 VT 81 87 Toronto NY NH Lake Ontario QEW Syracuse Niagara Rochester Falls 90 90 Buffalo Boston Welcome and thank you 81 Albany MA Lake Erie 88 86 90 for picking up the 2019 Guide. 17 87 90 Erie 17 CT RI We are very proud to be the home of Letchworth State Park, 79 PA Scranton and invite you to experience its majestic beauty and see why New York City it was voted #1 State Park in the US, and #1 attraction in New York State. 81 NJ Harrisburg Pittsburgh Newark After your visit to Letchworth State Park, there is plenty more adventure Philadelphia waiting just a short drive away. Enjoy a historic train excursion aboard the Arcade & Attica Railroad, get up-close with exotic animals at Hidden Valley Animal Adventure, and enjoy delicious food while watching a • Albany, NY – 3.75 hours drive-in movie at the one-of-a-kind Charcoal Corral and Silver Lake Twin • Cleveland, OH – 3.25 hours Drive-in. These are just a few of the fun and exciting adventures that await you here in Wyoming County, New York. • Hamilton, Canada – 1.75 hours • New York City, NY – 5 hours For more information, be sure to visit our mobile friendly website • Pittsburgh, PA – 3.75 hours GoWyomingCountyNY.com. We invite you and your family to visit and let • Toronto, Canada – 2.5 hours us be your guide, as you plan an experience that will last a lifetime. -

2021-04.20.20211.Pdf

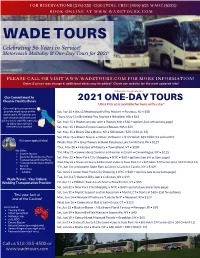

FOR RESERVATIONS (518) 355-4500 | TOLL-FREE (800) 955-WADE (9233) B O O K O N L I N E A T W W W . W A D E T O U R S . C O M WADE TOURS Celebrating 95 Years in Service! Motorcoach Multiday & One-Day Tours for 2021! PLEASE CALL OR VISIT WWW.WADETOURS.COM FOR MORE INFORMATION! Dates & prices may change & additional dates may be added! Check our website for the most updated info! *All prices are per person* Our Commitment to 2021 ONE-DAY TOURS Clean & Healthy Buses Utica Pick up is available for tours with a star* Our small group experiences provide ample space on the Sat, Apr 24 • Ikea & Meadowland's Flea Market • Paramus, NJ • $50 motorcoach. All surfaces are spot-cleaned and disinfected Thurs, May 13 • Brimfield Flea Market • Brimfield, MA • $45 before every trip! We want you Sat, May 15 • Boston on your own • Boston, MA • $60 + options (see attractions page) to enjoy your outing in freshness and comfort. Sat, May 15 • Boston Encore Casino • Boston, MA • $55 Sat, May 15 • Bronx Zoo • Bronx, NY • $80 Adult / $70 Child (3-12) Sun, May 16 • Dover Nascar • Dover, Delaware • $129 Adult, $89 Child (14 and under) It’s your special day! Wedn, May 19 • Grey Towers & Hotel Fauchere Lunch • Milford, PA • $125 Thur, May 20 • Friesians of Majesty • Townshend, VT • $109 We Offer: Shuttle Service *Fri, May 21 • Sonnenberg Gardens & Mansion & Cruise • Canandaigua, NY • $115 Bachelor/Bachelorette Party Sat, May 22 • New York City Shopping • NYC • $60 + options (see attractions page) Transportation Bridal Party Transportation Guest Shuttle Wed, May 26 •