Yellowstone and Other National Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prepared in Cooperation with the National Park Service Open- File

Form 9-014 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER RESOURCES OF YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK, WYOMING, MONTANA, AND IDAHO by Edward R. Cox Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Open- file report February 1973 U. S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 16 08863-3 831-564 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Geological Survey Water resources of Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho by Edward R. Cox Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Open* file report 73" February 1973 -1- Contents Iage Abstract ....... .... ................................... 9 Introduction-- - ....... ........ .................. n Location and extent of the area 12 Topography and drainage* -- - - - . --. -- .--..-- 13 Climate - - ................ 16 Previous investigations- -- .......................... 20 Methods of investigation . 21 Well and station numbers- ..... .... ........... .... 24 Acknowledgments---------------- - - 25 Geology-- - .............. ....... ......... ....... 26 Geologic units and their water-bearing characteristics 26 Precambrian rocks------------ -- - - -- 31 Paleozoic rocks ------- .. .--. -.- 31 Mesozoic rocks-- ,........--....-....---..-..---- .- 35 Cenozoic rocks- ....... ............................ 36 Tertiary rocks-- ........... ............... - 36 Tertiary and Quaternary rocks-- -- - - 38 Rhyolite - ............ 38 Basalt--- - ....................... .... 42 Quaternary rocks- - ...-. .-..-... ........ 44 Glacial deposits---- - .-- - 44 Lacustrine deposits---- - - 47 Hot-springs -

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

Human Impacts on Geyser Basins

volume 17 • number 1 • 2009 Human Impacts on Geyser Basins The “Crystal” Salamanders of Yellowstone Presence of White-tailed Jackrabbits Nature Notes: Wolves and Tigers Geyser Basins with no Documented Impacts Valley of Geysers, Umnak (Russia) Island Geyser Basins Impacted by Energy Development Geyser Basins Impacted by Tourism Iceland Iceland Beowawe, ~61 ~27 Nevada ~30 0 Yellowstone ~220 Steamboat Springs, Nevada ~21 0 ~55 El Tatio, Chile North Island, New Zealand North Island, New Zealand Geysers existing in 1950 Geyser basins with documented negative effects of tourism Geysers remaining after geothermal energy development Impacts to geyser basins from human activities. At least half of the major geyser basins of the world have been altered by geothermal energy development or tourism. Courtesy of Steingisser, 2008. Yellowstone in a Global Context N THIS ISSUE of Yellowstone Science, Alethea Steingis- claimed they had been extirpated from the park. As they have ser and Andrew Marcus in “Human Impacts on Geyser since the park’s establishment, jackrabbits continue to persist IBasins” document the global distribution of geysers, their in the park in a small range characterized by arid, lower eleva- destruction at the hands of humans, and the tremendous tion sagebrush-grassland habitats. With so many species in the importance of Yellowstone National Park in preserving these world on the edge of survival, the confirmation of the jackrab- rare and ephemeral features. We hope this article will promote bit’s persistence is welcome. further documentation, research, and protection efforts for The Nature Note continues to consider Yellowstone with geyser basins around the world. Documentation of their exis- a broader perspective. -

National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructil'.r!§ ~ ~ tloDpl lj~~r Bulletin How to Complete the Mulliple Property Doc11mentatlon Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the req lBtEa\oJcttti~ll/~ a@i~8CPace, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items X New Submission Amended Submission AUG 1 4 2015 ---- ----- Nat Register of Historie Places A. Name of Multiple Property Listing NatioAal Park Service National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Pre-Mission 66 era, 1945-1955; Mission 66 program, 1956-1966; Parkscape USA program, 1967-1972, National Park Service, nation-wide C. Form Prepared by name/title Ethan Carr (Historical Landscape Architect); Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Ph.D., (Historian, Architectural); Len Warner (Historian). The Collaborative Inc.'s 2012-2013 team comprised Rodd L. Wheaton (Architectural Historian and Supportive Research), Editor and Contributing Author; John D. Feinberg, Editor and Contributing Author; and Carly M. Piccarello, Editor. organization the Collaborative, inc. date March 2015 street & number ---------------------2080 Pearl Street telephone 303-442-3601 city or town _B_o_ul_d_er___________ __________st_a_te __ C_O _____ zi~p_c_o_d_e_8_0_30_2 __ _ e-mail [email protected] organization National Park Service Intermountain Regional Office date August 2015 street & number 1100 Old Santa Fe Trail telephone 505-988-6847 city or town Santa Fe state NM zip code 87505 e-mail sam [email protected] D. -

Karl Moon Cards

Tschanz Rare Books RareBooksLAX Boarding October 5-6, 2019 @ The Proud Bird Usual terms. Items Subject to prior sale. Call, text: 801-641-2874 Or email: [email protected] to confirm availability. Domestic shipping: $10 International and overnight shipping billed at cost. Modoc War 1- Watkins, Carleton E. [Louis Heller] Donald McKay and Jack's Capturers. San Francisco: Watkins Yosemite Art Gallery, [1873]. Albumen photograph [7.5 cm x 10 cm] on a tan 'Watkins Yosemite Art Gallery' mount [8.5 cm x 13 cm]. Wear to mount. "The only genuine Photographs of Captain Jack, and the Modoc Indians." The Modoc War was the only major conflict in California between the indigenous people of the area and the U.S. Army. After Captain Jack's surrender at Willow Creek in June of 1873 the surviving Modocs were forced to relocate to the Quapaw Agency in Oklahoma. Carleton E. Watkins (1829-1916) was one of the finest photographers of the nineteenth century. Between 1854 and 1891 he documented the American West from southern California to British Columbia and inland to Montana, Utah, and Arizona. He was a sympathetic and masterful recorder; whose pictures possess a clarity and strength equal to the magnificence of the land. His photographs of Yosemite so captured the imagination of legislators that Congress moved to preserve the area as a wilderness. $2,500 Grenville Dodge and the U.P. Commission 2- Savage, Charles Roscoe. Grenville M. Dodge and the Union Pacific Railroad Commission. Salt Lake City: Savage & Ottinger, [1867]. Carte de visite. Albumen [5.5 cm x 9.5 cm] photograph on the original cream-colored mount [6 cm x 10 cm] Savage & Ottinger backstamp with a contemporary(?) pencil notation identifying Dodge. -

100M Dash (5A Girls) All Times Are FAT, Except

100m Dash (5A Girls) All times are FAT, except 2 0 2 1 R A N K I N G S A L L - T I M E T O P - 1 0 P E R F O R M A N C E S 1 12 Nerissa Thompson 12.35 North Salem 1 Margaret Johnson-Bailes 11.30a Churchill 1968 2 12 Emily Stefan 12.37 West Albany 2 Kellie Schueler 11.74a Summit 2009 3 9 Kensey Gault 12.45 Ridgeview 3 Jestena Mattson 11.86a Hood River Valley 2015 4 12 Cyan Kelso-Reynolds 12.45 Springfield 4 LeReina Woods 11.90a Corvallis 1989 5 10 Madelynn Fuentes 12.78 Crook County 5 Nyema Sims 11.95a Jefferson 2006 6 10 Jordan Koskondy 12.82 North Salem 6 Freda Walker 12.04c Jefferson 1978 7 11 Sydney Soskis 12.85 Corvallis 7 Maya Hopwood 12.05a Bend 2018 8 12 Savannah Moore 12.89 St Helens 8 Lanette Byrd 12.14c Jefferson 1984 9 11 Makenna Maldonado 13.03 Eagle Point Julie Hardin 12.14c Churchill 1983 10 10 Breanna Raven 13.04 Thurston Denise Carter 12.14c Corvallis 1979 11 9 Alice Davidson 13.05 Scappoose Nancy Sim 12.14c Corvallis 1979 12 12 Jada Foster 13.05 Crescent Valley Lorin Barnes 12.14c Marshall 1978 13 11 Tori Houg 13.06 Willamette Wind-Aided 14 9 Jasmine McIntosh 13.08 La Salle Prep Kellie Schueler 11.68aw Summit 2009 15 12 Emily Adams 13.09 The Dalles Maya Hopwood 12.03aw Bend 2016 16 9 Alyse Fountain 13.12 Lebanon 17 11 Monica Kloess 13.14 West Albany C L A S S R E C O R D S 18 12 Molly Jenne 13.14 La Salle Prep 9th Kellie Schueler 12.12a Summit 2007 19 9 Ava Marshall 13.16 South Albany 10th Kellie Schueler 12.01a Summit 2008 20 11 Mariana Lomonaco 13.19 Crescent Valley 11th Margaret Johnson-Bailes 11.30a Churchill 1968 -

Grand Canyon; No Trees As Large Or As the Government Builds Roads and Trails, Hotels, Cabins GASOLINE Old As the Sequoias

GET ASSOCIATED WITH SMILING ASSOCIATED WESTERN DEALERS NATIONAL THE FRIENDLY SERVICE r OF THE WEST PARKS OUR NATIONAL PARKS "STATURE WAS GENEROUS first, and then our National sunny wilderness, for people boxed indoors all year—moun Government, in giving us the most varied and beautiful tain-climbing, horseback riding, swimming, boating, golf, playgrounds in all the world, here in Western America. tennis; and in the winter, skiing, skating and tobogganing, You could travel over every other continent and not see for those whose muscles cry for action—Nature's loveliness as many wonders as lie west of the Great Divide in our for city eyes—and for all who have a lively curiosity about own country . not as many large geysers as you will find our earth: flowers and trees, birds and wild creatures, here in Yellowstone; no valley (other nations concede it) as not shy—and canyons, geysers, glaciers, cliffs, to show us FLYING A strikingly beautiful as Yosemite; no canyon as large and how it all has come to be. vividly colored as our Grand Canyon; no trees as large or as The Government builds roads and trails, hotels, cabins GASOLINE old as the Sequoias. And there are marvels not dupli and camping grounds, but otherwise leaves the Parks un touched and unspoiled. You may enjoy yourself as you wish. • cated on any scale, anywhere. Crater Lake, lying in the cav The only regulations are those necessary to preserve the ity where 11 square miles of mountain fell into its own ASSOCIATED Parks for others, as you find them—and to protect you from MAP heart; Mt. -

Dear Friends of the History of Art Department: I Hope Your Autumn

TO THE ALUMNI OF THE HISTORY OF ART: ear Friends of the History of Art Department: I hope your autumn was as Dlovely as ours in Philadelphia. With characteristic enthusiasm, we launched the fall semester, offering courses that included our usual repertory of VOLUME 1 ISSUE 8 studies in the art and architecture of ancient Near East to that of today, three fresh- 2000 man seminars, and additional offerings in Minoan and Mycenaean Art, German art, the iconography of the Latin Middle Ages, and a course in CGS in twentieth-cen- INSIDE tury design. Christine Poggi returned to the classroom after a year’s fellowship leave in which she worked on her book on Italian Futurism, and Renata Holod began a Faculty News 2 year’s leave to carry out the documentation and interpretive work on her field work Art History Undergraduate at Jerba. We breathed a sigh of relief when we succeeded in retaining Holly Pittman Advisory Board 2 after a “raid” from Columbia. Our faculty continues to provide major leadership to the Penn community: Continuing his service as Director of College Houses and International Conference on Academic Services is David Brownlee, who has done wonders with this program. “The Culture of Exchange” 4 Our newest faculty member, Stephen Campbell, a specialist in the Italian A Tree Renaissance, is spending this year at I Tatti on a fellowship. Here at home, we wel- Grows Near Furness 5 comed to our staff Tammy Betterson, Administrative Assistant, who came to us from Political Science. Our students have done quite well, graduate students giving Traveling Students 5 papers at major professional meetings, and undergraduates as well as graduates Lectures During 1999 6 benefiting from the resources of the travel funds to which you have so thoughtfully contributed. -

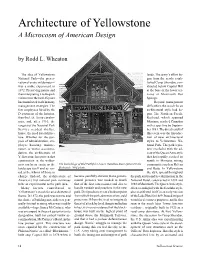

Architecture of Yellowstone a Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L

Architecture of Yellowstone A Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L. Wheaton The idea of Yellowstone lands. The army’s effort be- National Park—the preser- gan from the newly estab- vation of exotic wilderness— lished Camp Sheridan, con- was a noble experiment in structed below Capitol Hill 1872. Preserving nature and at the base of the lower ter- then interpreting it to the park races at Mammoth Hot visitors over the last 125 years Springs. has manifested itself in many Beyond management management strategies. The difficulties, the search for an few employees hired by the architectural style had be- Department of the Interior, gun. The Northern Pacific then the U.S. Army cavalry- Railroad, which spanned men, and, after 1916, the Montana, reached Cinnabar rangers of the National Park with a spur line by Septem- Service needed shelter; ber 1883. The direct result of hence, the need for architec- this event was the introduc- ture. Whether for the pur- tion of new architectural pose of administration, em- styles to Yellowstone Na- ployee housing, mainte- tional Park. The park’s pio- nance, or visitor accommo- neer era faded with the ad- dation, the architecture of vent of the Queen Anne style Yellowstone has proven that that had rapidly reached its construction in the wilder- zenith in Montana mining ness can be as exotic as the The burled logs of Old Faithful’s Lower Hamilton Store epitomize the communities such as Helena landscape itself and as var- Stick style. NPS photo. and Butte. In Yellowstone ied as the whims of those in the style spread throughout charge. -

Yellowstone National Park! Renowned Snowcapped Eagle Peak

YELLOWSTONE THE FIRST NATIONAL PARK THE HISTORY BEHIND YELLOWSTONE Long before herds of tourists and automobiles crisscrossed Yellowstone’s rare landscape, the unique features comprising the region lured in the West’s early inhabitants, explorers, pioneers, and entrepreneurs. Their stories helped fashion Yellowstone into what it is today and initiated the birth of America’s National Park System. Native Americans As early as 10,000 years ago, ancient inhabitants dwelled in northwest Wyoming. These small bands of nomadic hunters wandered the country- side, hunting the massive herds of bison and gath- ering seeds and berries. During their seasonal travels, these predecessors of today’s Native American tribes stumbled upon Yellowstone and its abundant wildlife. Archaeologists have discov- ered domestic utensils, stone tools, and arrow- heads indicating that these ancient peoples were the first humans to discover Yellowstone and its many wonders. As the region’s climate warmed and horses Great Fountain Geyser. NPS Photo by William S. Keller were introduced to American Indian tribes in the 1600s, Native American visits to Yellowstone became more frequent. The Absaroka (Crow) and AMERICA’S FIRST NATIONAL PARK range from as low as 5,314 feet near the north Blackfeet tribes settled in the territory surrounding entrance’s sagebrush flats to 11,358 feet at the Yellowstone and occasionally dispatched hunting Welcome to Yellowstone National Park! Renowned snowcapped Eagle Peak. Perhaps most interesting- parties into Yellowstone’s vast terrain. Possessing throughout the world for its natural wonders, ly, the park rests on a magma layer buried just one no horses and maintaining an isolated nature, the inspiring scenery, and mysterious wild nature, to three miles below the surface while the rest of Shoshone-Bannock Indians are the only Native America’s first national park is nothing less than the Earth lies more than six miles above the first American tribe to have inhabited Yellowstone extraordinary. -

Winter 2017 Calendar of Events

winter 2017 Calendar of events Agamemnon by Aeschylus Adapted by Simon Scardifield DIRECTED BY SONNY DAS January 27–February 5 Josephine Louis Theater In this issue The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane by Kate DiCamillo 2 Leaders out of the gate Adapted by Dwayne Hartford 4 The Chicago connection Presented by Imagine U DIRECTED BY RIVES COLLINS 8 Innovation’s next generation February 3–12 16 Waa-Mu’s reimagined direction Hal and Martha Hyer Wallis Theater 23 Our community Urinetown: The Musical Music and lyrics by Mark Hollmann 26 Faculty focus Book and lyrics by Greg Kotis 30 Alumni achievements DIRECTED BY SCOTT WEINSTEIN February 10–26 34 In memory Ethel M. Barber Theater 36 Communicating gratitude Danceworks 2017: Current Rhythms ARTISTIC DIRECTION BY JOEL VALENTÍN-MARTÍNEZ February 24–March 5 Josephine Louis Theater Fuente Ovejuna by Lope de Vega DIRECTED BY SUSAN E. BOWEN April 21–30 Ethel M. Barber Theater Waa-Mu 2017: Beyond Belief DIRECTED BY DAVID H. BELL April 28–May 7 Cahn Auditorium Stick Fly by Lydia Diamond DIRECTED BY ILESA DUNCAN May 12–21 Josephine Louis Theater Stage on Screen: National Theatre Live’s In September some 100 alumni from one of the most esteemed, winningest teams in Encore Series Josephine Louis Theater University history returned to campus for an auspicious celebration. Former and current members of the Northwestern Debate Society gathered for a weekend of events surround- No Man’s Land ing the inaugural Debate Hall of Achievement induction ceremony—and to fete the NDS’s February 28 unprecedented 15 National Debate Tournament wins, the most recent of which was in Saint Joan 2015. -

2016 Experience Planner a Guide to Lodging, Camping, Dining, Shopping, Tours and Activities in Yellowstone Don’T Just See Yellowstone

2016 Experience Planner A Guide to Lodging, Camping, Dining, Shopping, Tours and Activities in Yellowstone Don’t just see Yellowstone. Experience it. MAP LEGEND Contents DINING Map 2 OF Old Faithful Inn Dining Room Just For Kids 3 Ranger-Led Programs 3 OF Bear Paw Deli Private Custom Tours 4 OF Obsidian Dining Room Rainy Day Ideas 4 OF Geyser Grill On Your Own 5 Wheelchair Accessible Vehicles 6 OF Old Faithful Lodge Cafeteria Road Construction 6 GV Grant Village Dining Room GV Grant Village Lake House CL Canyon Lodge Dining Room Locations CL Canyon Lodge Cafeteria CL Canyon Lodge Deli Mammoth Area 7-9 LK Lake Yellowstone Hotel Dining Room Old Faithful Area 10-14 Lake Yellowstone Area 15-18 LK Lake Yellowstone Hotel Deli Canyon Area 19-20 LK Lake Lodge Cafeteria Roosevelt Area 21-22 M Mammoth Hot Springs Dining Room Grant Village Area 23-25 Our Softer Footprint 26 M Mammoth Terrace Grill Campground Info 27-28 RL Roosevelt Lodge Dining Room Animals In The Park 29-30 RL Old West Cookout Thermal Features 31-32 Winter 33 Working in Yellowstone 34 SHOPPING For Camping and Summer Lodging reservations, a $15 non-refundable fee will OF be charged for any changes or cancellations Bear Den Gift Shop that occur 30 days prior to arrival. For OF Old Faithful Inn Gift Shop cancellations made within 2 days of arrival, OF The Shop at Old Faithful Lodge the cancellation fee will remain at an amount GV Grant Village Gift Shop equal to the deposit amount. CL Canyon Lodge Gift Shop (Dates and rates in this Experience Planner LK Lake Hotel Gift Shop are subject to change without notice.