The Long View After 20 Years As Artistic Director of East West Players, TIM DANG Eyes the Challenges Unmet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

There Was a Small Fly

THERE WAS A SMALL FLY A G D there was a small fly who started a band Em G A D the fly loved to jam so she started a band maybe they'll play in Japan A G D F#m G she hired a spider to play the bass he made a funny face when he played the bass A G D she hired the spider to be in the band Em G A D the fly loved to jam so she started a band maybe they'll play in Japan A G D F#m G she hired a bird to play xylophone what a lovely tone when she played xylophone F#m G A G D she hired the bird to jam with the spider she hired the spider to be in the band Em G A D the fly loved to jam so she started a band maybe they'll play in Japan A G D F#m G she hired a cat to play the piano the cat was a pro at playing piano F#m G F#m G she hired the cat to jam with the bird she hired the bird to jam with the spider A G D she hired the spider to be in the band Em G A D the fly loved to jam so she started a band maybe they'll play in Japan A G D F#m G she hired a dog to play the guitar that dog was a star when she played the guitar F#m G F#m G she hired the dog to jam with the cat he hired the cat to jam with the bird F#m G A G D she hired the bird to jam with the spider she hired the spider to be in the band Em G A D the fly loved to jam so she started a band maybe they'll play in Japan A G D F#m G she hired a goat to play the drums the goat was all thumbs but was great on the drums F#m G F#m G she hired the goat to jam with the dog she hired the dog to jam with the cat F#m G F#m G she hired the cat to jam with the bird she hired the bird to jam with the spider -

Qt7js418zn.Pdf

UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies Title Chapter Two from Global Families: A History of Asian International Adoption in America Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7js418zn Journal Journal of Transnational American Studies, 8(1) Author Choy, Catherine Ceniza Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.5070/T881036679 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of Transnational American Studies (JTAS) 8.1 (2017) Global Families A History of Asian International Adoption in America Catherine Ceniza Choy a NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London 9780814717226_choy.indd 3 8/9/13 3:12 PM Journal of Transnational American Studies (JTAS) 8.1 (2017) NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress.org © 2013 by New York University All rights reserved References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Choy, Catherine Ceniza, 1969- Global families : a history of Asian international adoption in America / Catherine Ceniza Choy. pages cm. — (Nation of newcomers : immigrant history as American history) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8147-1722-6 (cl : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-4798-9217-4 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Intercountry adoption—United States. 2. Intercountry adoption—Asia. 3. Adopted children—United States. 4. Adoption—United States. 5. Asian Americans. I. Title. HV875.5.C47 2013 362.734—dc23 2013016966 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. -

Feeding Your Family Family

A 15 Minute Family What Resources will I Need? Devotional Guide 1. A Good Study Bible Feeding Your 1. Read the Bible (5 Min) If reading from an adult version of the Bible, at least one parent will need a copy Read an age-appropriate Bible for your of a good study Bible, to assist in family and seek to apply it to their lives. understanding the Bible “on the fly.” Family It may be a few verses or a paragraph or Consider the “ESV Study Bible.” two. Make it upbeat, lively, and fun. Engage younger children through picture 2. An Age Appropriate Bible for All And these words that I command you Bibles and creative voices. Engage older If your child can to calmly hold a book, he today shall be on your heart. You shall children through a discussion of current or she should have their own Bible. For events or ideas. pre-readers, consider “The Big Picture teach them diligently to your children, 2. Sing to the Lord (3 Min) Story Bible” by Crossway. For school-aged and shall talk of them when you sit in children, consider the “ESV Seek & Find If you feel comfortable singing, pick a your house, and when you walk by Bible” or the “NIrV Adventure Bible.” song or two that is age-appropriate for Children junior high & older will need an the way, and when you lie down, and your family. adult Bible, preferable a study Bible. when you rise. (Deut. 6:6-7 ESV) 3. Memorize a Verse (2 Min) 3. -

Pg. 03 Women Pg

The NATIONAL NeWSPAPeR Of The JACL Pg. 04 tamlyn tomita presents the 2012 v3 voice Award to Jocelyn Wang. Pg. 05 frances Kai-Hwa Wang on going to temple. MADPg. 03 WOMeN Pg. 06 HOW JeANNe KONisHi AND Her JACL board approves the 2013-14 budget. frieNDs reWrOte ADvertisiNg # 3196 / VOL. 155, NO. 5 ISSN: 0030-8579 WWW.PACIFICCITIZEN.ORG SEPT. 7 - 20, 2012 2 Sept. 7-20, 2012 LETTERS HOW to REACH US E-mail: [email protected] Letters To THE MISSING DOCUMENT FROM THE Online: www.pacificcitizen.org Tel: (213) 620-1767 ‘POWER OF WORDS’ HANDBOOK Fax: (213) 620-1768 The Editor Mail: 250 E. First Street, Suite 301 { { Los Angeles, CA 90012 In the Rafu Shimpo (July 17, 2012), Andy Noguchi, a leading member The question then arises: how many people in America since 1942 read STAFF of the Power of Words II Committee, gave an excellent report and review or even know of this exclusion order? Upon reading it the people will Executive Editor of the “Power of Words” handbook. The handbook was unanimously realize that this injustice did happen to us in this country and perhaps voted for and approved by the National JACL Council during the recent to resolve that it never again happen to any other people. A companion Assistant Editor national convention. question is then: how many Nikkei have read or even know of this his- Reporter I have read both drafts of the handbook and highly recommended that it toric document? Can one imagine back in April 1942 the Nisei reading Nalea J. -

Thanks and Congratulates

ATHE Annual Awards Ceremony Thursday, August 1, 2013 – 5:00 PM – 6:00 PM Grand Cypress Ballroom DEF, Ballroom Level ATHE proudly salutes its nine award winners in this plenary, followed by the Keynote presentation . Vice President for Awards, Kevin Wetmore and his 2013 Awards Committee members will present the award recipients to the conference attendees . Ellen Stewart Career Achievement Subsequent plays include The House of Sleeping Beauties Award for Professional Theatre (adapted from a novel by Kawabata Yasunari), The Sound of a Voice (subsequently adapted into an opera with P David Henry Hwang is the 2013 recipient of the Ellen (L) Phillip Glass), Rich Relations, Face Value, Trying to Find (L) Stewart Career Achievement Award for Professional Chinatown, Golden Child and an adaptation of Peer Gynt, Theatre. among others. His play M. Butterfly premiered in 1988 at AY David Henry Hwang is an Obie-award winning playwright the Eugene O’Neill Theatre on Broadway, running for 777 Bill thanks Doan who is also the first Asian-American to win a Tony Award performances and winning the John Gassner Award, the for Best Play. Born in Los Angeles and Drama Desk Award, the Outer Critics Circle professor of theatre and associate dean educated at Stanford and Yale, Hwang Award, the Tony Award for Best Play and for administration, research & graduate studies studied playwriting under Sam Hwang’s second listing as a finalist Shepard and Maria Irene Fornes. for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. FOB, his first professionally He has also written numerous produced play, premiered at books for musical and opera, the Stanford Asian American including a revised Flower Theatre Project in 1979 Drum Song, Tarzan, Aida president 2011–13 before being mounted and The Fly. -

Masaaki Hatsumi and Togakure Ryu

How Ninja Conquered the World THE TIMELINE OF SHINOBI POP CULTURE’S WORLDWIDE EXPLOSION Version 1.3 ©Keith J. Rainville, 2020 How did insular Japan’s homegrown hooded set go from local legend to the most marketable character archetype in the world by the mid-1980s? VN connects the dots below, but before diving in, please keep a few things in mind: • This timeline is a ‘warts and all’ look at a massive pop-culture phenomenon — meaning there are good movies and bad, legit masters and total frauds, excellence and exploitation. It ALL has to be recognized to get a complete picture of why the craze caught fire and how it engineered its own glass ceiling. Nothing is being ranked, no one is being endorsed, no one is being attacked. • This is NOT TO SCALE, the space between months and years isn’t literal, it’s a more anecdotal portrait of an evolving phenomenon. • It’s USA-centric, as that’s where VN originates and where I lived the craze myself. And what happened here informed the similar eruptions all over Europe, Latin America etc. Also, this isn’t a history of the Japanese booms that predated ours, that’s someone else’s epic to outline. • Much of what you see spotlighted here has been covered in more depth on VintageNinja.net over the past decade, so check it out... • IF I MISSED SOMETHING, TELL ME! I’ll be updating the timeline from time to time, so if you have a gap to fill or correction to offer drop me a line! Pinholes of the 1960s In Japan, from the 1600s to the 1960s, a series of booms and crazes brought the ninja from shadowy history to popular media. -

Snehal Desai

East West Players and Japanese American Cultural & Community Center (JACCC) By Special Arrangement with Sing Out, Louise! Productions & ATA PRESENT BOOK BY Marc Acito, Jay Kuo, and Lorenzo Thione MUSIC AND LYRICS BY Jay Kuo STARRING George Takei Eymard Cabling, Cesar Cipriano, Janelle Dote, Jordan Goodsell, Ethan Le Phong, Sharline Liu, Natalie Holt MacDonald, Miyuki Miyagi, Glenn Shiroma, Chad Takeda, Elena Wang, Greg Watanabe, Scott Watanabe, and Grace Yoo. SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN PROJECTION DESIGN PROPERTY DESIGN Se Hyun Halei Karyn Cricket S Adam Glenn Michael Oh Parker Lawrence Myers Flemming Baker FIGHT ALLEGIANCE ARATANI THEATRE PRODUCTION CHOREOGRAPHY PRODUCTION MANAGER PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER Cesar Cipriano Andy Lowe Bobby DeLuca Morgan Zupanski COMPANY MANAGER GENERAL MANAGER ARATANI THEATRE GENERAL MANAGER Jade Cagalawan Nora DeVeau-Rosen Carol Onaga PRESS REPRESENTATIVE MARKETING GRAPHIC DESIGN Davidson & Jim Royce, Nishita Doshi Choy Publicity Anticipation Marketing EXECUTIVE PRODUCER MUSIC DIRECTOR ORCHESTRATIONS AND CHOREOGRAPHER ARRANGEMENTS Alison M. Marc Rumi Lynne Shankel De La Cruz Macalintal Oyama DIRECTED BY Snehal Desai The original Broadway production of Allegiance opened on November 8th, 2015 at the Longacre Theatre in NYC and was produced by Sing Out, Louise! Productions and ATA with Mark Mugiishi/Hawaii HUI, Hunter Arnold, Ken Davenport, Elliott Masie, Sandi Moran, Mabuhay Productions, Barbara Freitag/Eric & Marsi Gardiner, Valiant Ventures, Wendy Gillespie, David Hiatt Kraft, Norm & Diane Blumenthal, M. Bradley Calobrace, Karen Tanz, Gregory Rae/Mike Karns in association with Jas Grewal, Peter Landin, and Ron Polson. World Premiere at the Old Globe Theater, San Diego, California. Barry Edelstein, Artistic Director; Michael G. -

Theater and the Makings of the Asian American Identity by by Jeffrey Nishimura

Asian American Literature: Discourses and Pedagogies 1 (2010) 27-34. Play(ing) in the Pear Garden: Theater and the Makings of the Asian American Identity By By Jeffrey Nishimura In Tripmaster Monkey (1989), Maxine Hong Kingston’s Sino-Ulysses, Wittman Ah Sing is a hip, Chinese American existentialist, wandering the streets of San Francisco. When he is not contemplating a bullet in the head, Wittman is declaring his artistic dreams to a stock boy at a San Francisco toy store where he is employed: I’m going to start a theater company. I’m naming it The Pear Garden Players of America. The Pear Garden was the cradle of civilization, where theater began on earth. Out among the trees, ordinary people made fools of themselves acting like kings and queens. As playwright and producer and director, I’m casting blind. That means the actors can be any race. Each member of the Tyrone family or the Lomans can be a different color. I’m including everything that is being left out, and everyone who has no place. My idea for the Civil Rights Movement is that we integrate jobs, schools, buses, housing, lunch counters, yes, and we also integrate theaters and parties. The dressing up. The dancing. The loving. The playing. Have you ever acted? Why don’t you join my theater company? I’ll make a part for you. (Kingston 52) It isn’t surprising that Wittman settles on this particular medium as the chance of his own Becoming, confessing: “I’m not ready for Being yet” (Kingston 52). -

Finding, Reclaiming, and Reinventing Identity Through DNA: the DNA Trail

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 23 (2012) Finding, Reclaiming, and Reinventing Identity through DNA: The DNA Trail Yuko KURAHASHI* The DNA Trail: A Genealogy of Short Plays about Ancestry, Identity, and Utter Confusion (2011) is a collection of seven fifteen-to-twenty minute plays by veteran Asian American playwrights whose plays have been staged nationally and internationally since the 1980s. The plays include Philip Kan Gotanda’s “Child Is Father to Man,” Velina Hasu Houston’s “Mother Road,” David Henry Hwang’s “A Very DNA Reunion,” Elizabeth Wong’s “Finding Your Inner Zulu,” Shishir Kurup’s “Bolt from the Blue,” Lina Patel’s “That Could Be You,” and Jamil Khoury’s “WASP: White Arab Slovak Pole.” Conceived by Jamil Khoury and commissioned and developed by Silk Road Theatre Project in Chicago in association with the Goodman Theatre, a full production of the seven plays was mounted at Silk Road Theatre Project in March and April 2010.1 On January 22, 2011, Visions and Voices: The USC Arts and Humanities Initiative presented a staged reading at the Uni- versity of Southern California, Los Angeles, using revised scripts. The staged reading was directed by Goodman Theatre associate producer Steve Scott, who had also directed the original production.2 San Francisco–based playwright Gotanda has written plays that reflect his yearning to learn the stories of his Japanese American parents, and their friends and relatives. His plays include A Song for a Nisei Fisherman (1980), The Wash (1985), Ballad of Yachiyo (1996), and Sisters *Associate Professor, Kent State University 285 286 YUKO KURAHASHI Matsumoto (1997). -

James Hong-Joong Kim Crd# 4649932

User Guidance www.adviserinfo.sec.gov IAPD Report JAMES HONG-JOONG KIM CRD# 4649932 Section Title Page(s) Report Summary 1 Qualifications 2 - 4 Registration and Employment History 5 i Please be aware that fraudsters may link to Investment Adviser Public Disclosure from phishing and similar scam websites, trying to steal your personal information or your money. Make sure you know who you’re dealing with when investing, and contact FINRA with any concerns. For more information read our investor alert on imposters. User Guidance www.adviserinfo.sec.gov IAPD Information About Representatives IAPD offers information on all current-and many former representatives. Investors are strongly encouraged to use IAPD to check the background of representatives before deciding to conduct, or continue to conduct, business with them. What is included in a IAPD report? IAPD reports for individual representatives include information such as employment history, professional qualifications, disciplinary actions, criminal convictions, civil judgments and arbitration awards. It is important to note that the information contained in an IAPD report may include pending actions or allegations that may be contested, unresolved or unproven. In the end, these actions or allegations may be resolved in favor of the representative, or concluded through a negotiated settlement with no admission or finding of wrongdoing. Where did this information come from? The information contained in IAPD comes from the Investment Adviser Registration Depository (IARD) and FINRA's Central Registration Depository, or CRD, (see more on CRD below) and is a combination of: · information the states require representatives and firms to submit as part of the registration and licensing process, and · information that state regulators report regarding disciplinary actions or allegations against representatives. -

Nickelodeon Masters the Elements with the Legend of Korra

For Immediate Release NICKELODEON MASTERS THE ELEMENTS WITH THE LEGEND OF KORRA London, UK – 29th April, 2013 – From the creators of the Hit Series Avatar: The Last Airbender, The Legend of Korra is set to premiere on Nickelodeon on Sunday, 7th July at 9:00am. The mythology from the critically acclaimed Avatar series continues in the new animation which follows a new Avatar named Korra, a 17-year-old headstrong and rebellious girl who continually challenges tradition on her quest to become a fully realized Avatar. New episodes of The Legend of Korra will premiere each Sunday at 9:00am. The Legend of Korra takes place 70 years after the events of Avatar: The Last Airbender and follows the next Avatar after Aang – a girl named Korra (Janet Varney) who is from the Southern Water Tribe. With three of the four elements under her belt (Earth, Water and Fire), Korra seeks to master Air. Her quest leads her to Republic City, the modern “Avatar” world that is a virtual melting pot where individuals from all nations live and thrive. Korra quickly discovers that the metropolis is plagued by crime as well as a revolution that threatens to rip the city apart. Under the tutelage of Aang’s son, Tenzin (J.K. Simmons), Korra begins her airbending training while dealing with the dangers at large. In the premiere episode, “Welcome to Republic City,” Korra leaves the safety of her home and travels to bustling Republic City to begin her airbending training. Once there, she is shocked to find a big city full of dangers. -

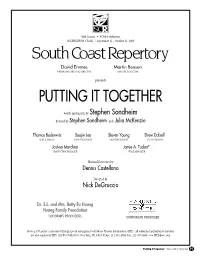

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager .............................................................