City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vandalism Runs Rampant on Trinity Campus

THE TRINITY TRIPOD Vol. 75 Issue 3 September 21, 1976 Vandalism Runs Rampant On Trinity Campus by Carl Roberts security, blames a small number gave their children everything If you walk into the Wheaton of students. He said, "Students they desired. After coming to dormitory, you will notice that the blame the townies. Maybe there are college, a student no longer has his ceiling is smashed beyond some townies partly responsible. way. He has to face many recognition, and that the exit signs But I'm positive that the greater frustrations. A prime example is are jerked loose. If you notice that part of damage to the campus is when the student suddenly realizes some of the walls at 216 New done by students." Garofolo said that there will not be a job waiting Britain have been kicked in, don't he believes that the college should for him upon graduation. In this blame it on last year's students. not be a sanctuary against age of self concern, a student Over the summer, the holes in the irresponsible behavior. He at- might not think twice about taking New Britain walls were repaired. tributes many of the problems on his frustrations out on someone Within two weeks of the start of campus to students' lack of con- else's property. school, they were kicked in again. sideration for others. "I don't see any short-term These are just two of several "We are definitely in a period of solution,"' Higgings said, "unless examples of recent vandalism on narcissism," commented Dr. -

ROBERT WYATT Title: ‘68 (Cuneiform Rune 375) Format: CD / LP / DIGITAL

Bio information: ROBERT WYATT Title: ‘68 (Cuneiform Rune 375) Format: CD / LP / DIGITAL Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: ROCK “…the [Jim Hendrix] Experience let me know there was a spare bed in the house they were renting, and I could stay there with them– a spontaneous offer accepted with gratitude. They’d just hired it for a couple of months… …My goal was to make the music I’d actually like to listen to. … …I was clearly imagining life without a band at all, imagining a music I could make alone, like the painter I always wanted to be.” – Robert Wyatt, 2012 Some have called this - the complete set of Robert Wyatt's solo recordings made in the US in late 1968 - the ultimate Holy Grail. Half of the material here is not only previously unreleased - it had never been heard, even by the most dedicated collectors of Wyatt rarities. Until reappearing, seemingly out of nowhere, last year, the demo for “Rivmic Melodies”, an extended sequence of song fragments destined to form the first side of the second album by Soft Machine (the band Wyatt had helped form in 1966 as drummer and lead vocalist, and with whom he had recorded an as-yet unreleased debut album in New York the previous spring), was presumed lost forever. As for the shorter song discovered on the same acetate, “Chelsa”, it wasn't even known to exist! This music was conceived by Wyatt while off the road during and after Soft Machine's second tour of the US with the Jimi Hendrix Experience, first in New York City during the summer of 1968, then in the fall of that year while staying at the Experience's rented house in California, where he was granted free access to the TTG recording facility during studio downtime. -

Gonzo Weekly

2 Another happened last year when the Rolling Stones dragged Mick Taylor away from undeserved obscurity, and played a series of barnstorming gigs including Glastonbury Festival, and another is going on at the moment and started last night. King Crimson have been, unarguable, one of the most idiosyncratic and artistically interesting bands for forty five years now, since they formed in 1968. Leader Robert Fripp left the music business some years ago, and King Crimson seem to have been on indefinite hiatus since about 2008. However, last year Fripp announced that the band will return, and this week, the new seven piece line-up played their first shows. The silence surrounding these shows is deafening. I spoke to Jakko Jakszyk who is the second guitarist and vocalist with the new King Crimson, last week on Facebook. He was understandably cagey about Dear Friends, what was happening. I asked how the rehearsals were going, and he said that they seemed OK but Welcome to another issue of the Gonzo Weekly. told me to ask him again after they had done a show or two. We are always being told how the music industry is in crisis and how record sales are plummeting. He will be back in the UK in October, apparently, However, once or twice a year there are still major so I will be doing my best to nail him down for a artistic and cultural events which take the western proper interview then. world by storm. The only review that I have found yet of the new One such has been Kate Bush’s renaissance band (and remember that this is being written on following her ongoing series of concerts in London. -

Read Fly Issue 2

• •••• j . • .. , • ,·· ·: 'rhc .Ldrd of fl l D.irgov1 ric Gould not find u dm·1ry l!'or J e llu tho Bour, his ndOi) Led niece Who'd spent all his ntoney On cartons of llo ney, A Si c.u.:ese cnnnon - not all in one piece A bicycle chain .l!'or a sadisrr, gar;;e And a pl&tinw:, doll \ii th ~ :::utile like a crec:.. se. "Alas!" said. the Lair·d "I ' li: nov1 very scared ! " (He tJ:::de a finn ha bit of telling the truth \/hen playing bnd;. ga:u,1on Or fishing for salmon Or v! hen he \'IClS trying to \1ork free a tooth ~ 1 hich l u.s t he \ ~c...::; do inti ) "I see trouble ' s 1ir e;ving 'I'hi:.': i s a 1uatter for (cthadoae liuth ! " il.uth ,·.etlw.done \tas a Latching c:r:ofm We ll-.i ~no < , n for her efi orts in CJ hes s in i~ ton Zoo. jhe'·d ,,edded a r [4t ··. 'l'o a one-legl_e d ba t, A leprous 6iraf1'e to a giant kangaroo. "use S'l'D" :3aid the Hear,full of glee, "She'll be her e to-night there'll be cooking to do 'l'he Jawe of l\eno1.n ,:as s oun SL.J irallinG dm.n on her t t,in-w;jine biped from .Dunba rton Yards; ::>be •·1hirleci through the sky Li ke a han.strung fly ·.ro l c:nd at sowe speed on the Laird 1 s pack of cards. -

Lynsey De Paul

2 don’t understand why so many people are angry with the recent iTunes promotion of U2’s new album. Now, don’t get me wrong. I am not saying this because I am a fan of the band, or because I think it is a remarkable record. It’s not, and I’m not. The band have made much better records in the past, and they have made considerably worse ones. That isn’t the issue. There have been times in my life when I have been quite impressed with the band’s output, although I would never have called myself a true blue fan. But that isn’t the issue either. The issue is why are so many people incensed by the fact that iTunes paid the band an undisclosed sum (said to be in the multiple millions) to send a copy of the record to everybody who had an iTunes account on the day in question? Those beneficiaries included Dear Friends, me, by the way – twice. Welcome to another issue of Gonzo Weekly The album can be removed from your playlists magazine. For the first time in quite a few with a couple of clicks of a mouse, and although issues, our own life has quietened down I believe it is slightly more complicated if you somewhat; Weird Weekends have come and have an iPhone, I truly don’t think it is going to gone, grand-daughters have been born, and we be that much of an issue. are back in the relative safety of our own little sanctum in North Devon. -

Canterbury Sound’ Andy Bennett UNIVERSITY of SURREY

Music, media and urban mythscapes: a study of the ‘Canterbury Sound’ Andy Bennett UNIVERSITY OF SURREY In this article I examine how recent developments in media and technology are both re-shaping conventional notions of the term ‘music scene’ and giving rise to new perceptions among music fans of the relationship between music and place. My empirical focus throughout the article is the ‘Canterbury Sound’, a term originally coined by music journalists during the late 1960s to describe the music of Canterbury1 jazz-rock group the Wilde Flowers, and groups subsequently formed by individual members of the Wilde Flowers – the most well known examples being Caravan, Hatfield and the North and Soft Machine (see Frame, 1986: 16; Macan, 1997; Stump, 1997; Martin, 1998), and a number of other groups with alleged Canterbury connections. Over the years a range of terms, for example ‘Motown’, the ‘Philadelphia Sound’ and, more recently, the ‘Seattle Sound’, have been used as a way of linking musical styles with particular urban spaces. For the most part, however, these terms have described active centres of production for music with a distinctive ‘sound’. In contrast, however, in its original context the Canterbury Sound was a rather more loosely applied term, the majority of groups and artists linked with the Canterbury Sound being London-based and sharing little in the way of a characteristic musical style. Since the mid-1990s, however, the term ‘Canterbury Sound’ has acquired a very different currency as a new generation of fans have constructed a discourse of Canterbury music that attempts to define the latter as a distinctive ‘local’ sound with character- istics shaped by musicians’ direct experience of life in the city of Canterbury. -

Une Discographie De Robert Wyatt

Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Discographie au 1er mars 2021 ARCHIVE 1 Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Ce présent document PDF est une copie au 1er mars 2021 de la rubrique « Discographie » du site dédié à Robert Wyatt disco-robertwyatt.com. Il est mis à la libre disposition de tous ceux qui souhaitent conserver une trace de ce travail sur leur propre ordinateur. Ce fichier sera périodiquement mis à jour pour tenir compte des nouvelles entrées. La rubrique « Interviews et articles » fera également l’objet d’une prochaine archive au format PDF. _________________________________________________________________ La photo de couverture est d’Alessandro Achilli et l’illustration d’Alfreda Benge. HOME INDEX POCHETTES ABECEDAIRE Les années Before | Soft Machine | Matching Mole | Solo | With Friends | Samples | Compilations | V.A. | Bootlegs | Reprises | The Wilde Flowers - Impotence (69) [H. Hopper/R. Wyatt] - Robert Wyatt - drums and - Those Words They Say (66) voice [H. Hopper] - Memories (66) [H. Hopper] - Hugh Hopper - bass guitar - Don't Try To Change Me (65) - Pye Hastings - guitar [H. Hopper + G. Flight & R. Wyatt - Brian Hopper guitar, voice, (words - second and third verses)] alto saxophone - Parchman Farm (65) [B. White] - Richard Coughlan - drums - Almost Grown (65) [C. Berry] - Graham Flight - voice - She's Gone (65) [K. Ayers] - Richard Sinclair - guitar - Slow Walkin' Talk (65) [B. Hopper] - Kevin Ayers - voice - He's Bad For You (65) [R. Wyatt] > Zoom - Dave Lawrence - voice, guitar, - It's What I Feel (A Certain Kind) (65) bass guitar [H. Hopper] - Bob Gilleson - drums - Memories (Instrumental) (66) - Mike Ratledge - piano, organ, [H. Hopper] flute. - Never Leave Me (66) [H. -

Viral Spiral Also by David Bollier

VIRAL SPIRAL ALSO BY DAVID BOLLIER Brand Name Bullies Silent Theft Aiming Higher Sophisticated Sabotage (with co-authors Thomas O. McGarity and Sidney Shapiro) The Great Hartford Circus Fire (with co-author Henry S. Cohn) Freedom from Harm (with co-author Joan Claybrook) VIRAL SPIRAL How the Commoners Built a Digital Republic of Their Own David Bollier To Norman Lear, dear friend and intrepid explorer of the frontiers of democratic practice © 2008 by David Bollier All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. The author has made an online version of the book available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license. It can be accessed at http://www.viralspiral.cc and http://www.onthecommons.org. Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 38 Greene Street, New York,NY 10013. Published in the United States by The New Press, New York,2008 Distributed by W.W.Norton & Company,Inc., New York ISBN 978-1-59558-396-3 (hc.) CIP data available The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. www.thenewpress.com A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org. Composition by dix! This book was set in Bembo Printed in the United States of America 10987654321 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 Part I: Harbingers of the Sharing Economy 21 1. -

Caravan Caravan Mp3, Flac, Wma

Caravan Caravan mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Caravan Country: New Zealand Released: 1972 Style: Psychedelic Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1597 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1208 mb WMA version RAR size: 1495 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 651 Other Formats: MOD ADX RA MMF MP4 DTS VOX Tracklist A1 Place Of My Own 4:00 A2 Ride 3:40 A3 Policeman 2:40 A4 Love Song With Flute 4:06 A5 Cecil Runs 4:05 B1 Magic Man 4:00 B2 Grandma's Lawn 3:20 B3 Where But For Caravan Would I? 8:55 Companies, etc. Record Company – Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. Manufactured By – MGM Records Division Recorded At – Advision Studios Published By – Miller Music Corp. Credits Cover [Cover Concept], Photography By – Richard Bennett Zeff Design, Graphics – Peter Dale Drums – Richard Coughlan Engineer – Gerald Chevin Engineer [Director Of Engineering] – Val Valentin Guitar, Bass, Vocals – Pye Hastings, Richard Sinclair Organ, Piano, Vocals – David Sinclair Producer – Tony Cox Sleeve Notes – Leslie Rubinstein Written-By – Brian Hopper (tracks: B3), David Sinclair, Julian Hastings*, Richard Coughlan, Richard Sinclair Notes Tan/brown center labels with catalogue number on the LEFT of the label, and no matrix on labels. Different to this other similar version whose labels show the Category and matrix on the RIGHT of the labels. Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: ASCAP Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year VLP 6011 Caravan Caravan (LP, Album, Mono) Verve Forecast VLP 6011 UK 1969 Caravan (CD, Album, RE, SomeWax -

Downbeat.Com February 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 .K. U DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT BUNKY GREEN & RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA // OMAR SOSA // JOHN MCNEIL // KEVIN EUBANKS // JAZZ VENUE GUIDE FEBRUARY 2011 FEBRUARY 2011 VOLUME 78 – NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser Circulation Assistant Alyssa Beach ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

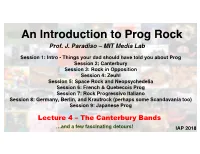

An Introduction to Prog Rock Prof

An Introduction to Prog Rock Prof. J. Paradiso – MIT Media Lab Session 1: Intro - Things your dad should have told you about Prog Session 2; Canterbury Session 3: Rock in Opposition Session 4: Zeuhl Session 5: Space Rock and Neopsychedelia Session 6: French & Quebecois Prog Session 7: Rock Progressivo Italiano Session 8: Germany, Berlin, and Krautrock (perhaps some Scandavania too) Session 9: Japanese Prog Lecture 4 – The Canterbury Bands …and a few fascinating detours! IAP 2018 The City of Canterbury London Up Here An amazingly creative bunch of emerging musicians hung out at Robert Wyatt’s House & environs in the mid 60s Memories Brian & Hugh Hopper, Richard Sinclair, Kevin Ayers formed The Wilde Flowers in the early 1960s – Daevid Allen, David Sinclair, Richard Coughlin, etc. in the mix too Leading to Soft Machine, Caravan, Gong, and Kevin Ayers solo career Enter Soft Machine! Robert Wyatt, Hugh Hopper, Mike Ratledge (Daevid Allen, Kevin Ayers) Jimi was their colleague, friend, and fan He gave them their sound… We Did It Again Early Soft Machine 1968 1969 Why Are We Sleeping? As Long as he Lies Perfectly Still Hung out and toured with Jimi Hendrix Fuzzbox and pedals on organ are iconic in Canterbury Music Very intense live band Hope for Happiness (Live @ Middle Earth Club) - 1967 Live in France - 1968 Kevin Ayers splits for his solo career 1969 1970 1972 1974 Rheinhardt And Geraldine / Colores Para Dolores (1970) The Confessions Of Doctor Dream: Irreversible Neural Damage (1974) Becoming a (psychedelic) Jazz Band 1970 1971 1972 Last -

Daytime Programme

DAYTIME PROGRAMME 10:30 – 10:50 Welcome. Health and safety notices, event concept and programme for the day. 10:50 – 11:20 Coffee break and introduction to the Archive Exhibition. 11:20 – 12:50 Panel 1: “Canterbury Sound” myths and realities Talks from: Professor Andy Bennett (Griffith Univesity, Australia) Geoffrey Richardson (Caravan) Brian Hopper (Wilde Flowers, Soft Machine) Jack Hues (Wang Chung/Jack Hues and the Quartet) Professor Murray Smith (Kent/Princeton Universities) + a discussion panel 12:50 – 13:00 Comfort break 13:00 – 13:45 Performance: Jack Hues and the Quartet 13:45 – 14:30 Lunch 14:30 – 16:00 Panel 2: Archives and futures of the online and offline “Canterbury Sound” Talks from Aymeric Leroy (Author of The Sound of Canterbury) Phil Howitt (Facelift fanzine founder) Dr Asya Draganova (Birmingham City University) and Professor Shane Blackman (CCCU) Alan Payne (University of Kent) + discussion panel 16:00 – 16:10 Comfort break 16:10 – 16:50 Performance by Koloto 16:50 – 17:00 Comfort break 17:00 – 18:00 Fan forum: mapping the spaces and places of the “Canterbury Sound” with the participation of fans + a short talk by Adam Brodigan on the inter-generational context of the Canterbury Sound. Final discussion and closing remarks for this section of the day. EVENING PROGRAMME (bar opens 18:30) 19:00 – 22:00: Lapis Lazuli and SoupSongs live music performances: in dialogue within the “Canterbury Sound” The SoupSongs were originally assembled with the participation of Robert Wyatt and specialise in performing his music. Each of the artists involved with the band has had an extraordinary music career in connection to the Canterbury Sound and beyond.