Cultural Differences in the Context of Fast Food Website Design: a Comparison of Taiwan and the United States Yin-Sin Chang Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demae-Can / 2484

Demae-can / 2484 COVERAGE INITIATED ON: 2017.12.25 LAST UPDATE: 2021.06.25 Shared Research Inc. has produced this report by request from the company discussed herein. The aim is to provide an “owner’s manual” to investors. We at Shared Research Inc. make every effort to provide an accurate, objective, neutral analysis. To highlight any biases, we clearly attribute our data and findings. We always present opinions from company management as such. The views are ours where stated. We do not try to convince or influence, only inform. We appreciate your suggestions and feedback. Write to us at [email protected] or find us on Bloomberg. Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. Demae-can / 2484 RCoverage LAST UPDATE: 2021.06.25 Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. | https://sharedresearch.jp INDEX How to read a Shared Research report: This report begins with the Trends and outlook section, which discusses the company’s most recent earnings. First-time readers should start at the later Business section. Executive summary ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Key financial data ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Recent updates ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Highlights ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

Boba Tea: Blending Drinks and Cultures

This material is exclusively prepared for Ringle Customers Ringle material written by Tutor Angela Kim Boba Tea: Blending Drinks and Cultures [source: http://theboola.com/a-comprehensive-non-scientific-ranking-of-boba-tea-at-yale/] 0 본 자료는 저작권 법에 의해 보호되는 저작물로, Ringle 사에 저작권이 존재합니다. 해당 자료에 대한 무단 복제/배포를 금하며, 해당 자료로 수익을 얻거나 이에 상응하는 혜택을 누릴 시 Ringle 과 사전 협의가 없는 경우 고소/고발 조치 될 수 있습니다. This material is exclusively prepared for Ringle Customers [Summary in English] I. Origins Within the past decade, boba tea, also known as “bubble tea,” has gained enormous popularity around the world. • Boba tea was created in Taiwan in the 1980s. Although the exact origin story is unknown, most people believe it was developed by Lin Hsiu Hui who added some tapioca pudding to her drink at a teahouse in Taichung, Taiwan. It became immediately popular and many street vendors began to serve boba at night markets. • The word “boba” can refer to both the broad category of drinks with chunky toppings or the black tapioca pearls themselves. • Boba pearls are made from tapioca that comes from the cassava root. The cassava plant is native to South America but came to Taiwan from Brazil during Japanese rule between 1895 to 1945. While “bubble tea” refers to the milk froth from shaking the cup, “boba” refers to the Taiwanese tapioca pearls. Often, the drink is called “bubble tea” on the East Coast while it is called “boba” on the West Coast more often. • In its most basic form, the drink includes black tea, milk, ice, and tapioca pearls. -

The JR Pass: 2 Weeks in Japan

Index Introduction to Travel in Japan………………………………… 1 - 7 Day 1 | Sakura Blooms in North Japan…………………….. 8 - 12 Day 2 |Culture in Kyoto…………………………………………… 13 - 18 Day 3 | Shrines and Bamboo Forests……………………….. 19 - 24 Day 4 | The Alpine Route………………………………………… 25 - 29 Day 5 | Takayama Mountain Village……………………….. 30 - 34 Day 6 | Tokyo by Day, Sendai at Night…………………….. 35 - 40 Day 7 | Exploring Osaka………………………………………….. 41 - 44 Day 8 | The 8 Hells of Beppu…………………………………… 45 - 50 Day 9 | Kawachi Fuji Gardens………………………………….. 51 - 53 Day 10 | Tokyo Indulgence………………………………………. 54 - 58 Day 11 | The Ryokan Experience at Mount Fuji……….. 59 - 64 Day 12 | The Fuji Shibazakura Festival……………………… 65 - 70 Day 13 | Harajuku and Shinjuku (Tokyo)…………………… 71 - 75 Day 14 | Sayonara!........................................................ 76 - 78 The Final Bill ……………………………………………………………. 79 1 We Owned the JR Pass: 2 Weeks in Japan May 29, 2015 | By Allan and Fanfan Wilson of Live Less Ordinary Cities can be hard to set apart when rattling past the backs of houses, on dimly lit train lines. Arriving to Tokyo it feels no different, and were it not for the alien neon lettering at junctions, we could have been in any city of the world. “It reminds me of China” Fanfan mutters at a time I was feeling the same. It is at this point where I realize just how little I know about Japan. My first impressions? It’s not as grainy as Akira Kurosawa movies, and nowhere near as animated as Manga or Studio Ghibli productions. This is how I know Japan; through movies and animation, with samurai and smiling eyes. I would soon go on to know and love Japan for many other reasons, expected and unexpected during our 2 week JR pass journeys. -

Spatial Competition and Marketing Strategy of Fast Food Chains in Tokyo

Geographical Review of Japan Vol. 68 (Ser. B), No. 1, 86-93, 1995 Spatial Competition and Marketing Strategy of Fast Food Chains in Tokyo Kenji ISHIZAKI* Key words: spatial competition,marketing strategy, nearest-neighbor spatial associationanalysis, fast food chain, Tokyo distributions of points, while Clark and Evans I. INTRODUCTION (1954) describe a statistic utilizing only a single set of points. This measure is suitable for de One of the important tasks of retail and res scribing the store distribution of competing taurant chain expansion is the development of firms such as retail chains. a suitable marketing strategy. In particular, a The nearest neighbor spatial association location strategy needs to be carefully deter value, R, is obtained as follows: mined for such chains, where store location is often the key to the successful corporate's R=ƒÁ0/ƒÁE (1) growth (Ghosh and McLafferty, 1987; Jones and The average nearest-neighbor distance, ƒÁ0, is Simmons, 1990). A number of chain entries into given by the same market can cause strong spatial com petition. As a result of this, retail and restaurant (2) chains are anxious to develop more accessible and well-defined location strategies. In restau where dAi is the distance between point i in type rant location, various patterns are respectively A distribution and its nearest-neighbor point in presented according to some types of restau type B distribution and dBj is the distance from rants (i.e. general full service, ethnic, fast food point j of type B to its nearest neighbor point of and so on) and stores of the same type are type A. -

Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/20/2016 GAIN Report Number: ID1640 Indonesia Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional Food Service Hotel Restaurant Institutional Update Approved By: Ali Abdi Prepared By: Fahwani Y. Rangkuti and Thom Wright Report Highlights: The Indonesian hotel and restaurant industries grew 6.25 and 3.89 percent in 2015, respectively. Industry contacts attribute the increase to continued urbanization, tourism, and MICE (Meeting, Incentive, Conference, and Exhibitions) development. The Bank of Indonesia expects that economic growth will fall around 4.9 to 5.3 percent in 2016 and 5.2 to 5.6 percent in 2017. Post: Jakarta I. MARKET SUMMARY Market Overview Indonesia is the most populous country in the ASEAN region with an estimated 2017 population of 261 million people. It is home to approximately 13,500 islands and hundreds of local languages and ethnic groups, although the population is mostly concentrated on the main islands of Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Papua. It is bestowed with vast natural resources, including petroleum and natural gas, lumber, fisheries and iron ore. Indonesia is a major producer of rubber, palm oil, coffee and cocoa. In 2015, Indonesian GDP declined to 4.79 percent. The Bank of Indonesia expects economic growth will reach between 4.9 and 5.3 percent in 2016 and 5.2 to 5.6 percent in 2017. This contrasts with growth rates above 6 percent during 2007 to 2012 period. Inflation has ranged between 2.79 (August) and 4.45 (March) during the January-October 2016 period, while the rupiah has remained weak vis-à- vis the U.S. -

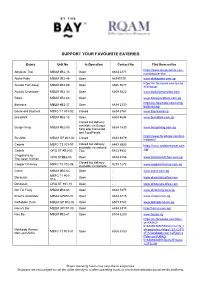

Support Your Favourite Eateries

SUPPORT YOUR FAVOURITE EATERIES Eatery Unit No In Operation Contact No. Find them online https://www.absolutethai.com. Absolute Thai MBLM #B2-16 Open 6634 2371 my/absolute-thai Aloha Poke MBLM #B2-46 Open 66340730 www.alohapoke.com.sg https://m.facebook.com/arcad Arcade Fish Soup MBLM #B2-69 Open 8566 9077 efishsoup/ Awfully Chocolate MBLM #B2-33 Open 6509 9422 www.awfullychocolate.com Boost MBLM #B2-64 Open www.boostjuicebars.com.sg https://m.facebook.com/living. Botanica MBLM #B2-37 Open 6634 2330 botanica.sg/ Boulevard Bayfront MBFC T1 #01-02 Closed 6634 8761 www.Boulevard.sg Breadtalk MBLM #B2-18 Open 6509 4644 www.breadtalk.com.sg Closed but delivery available via Burger Burger King MBLM #B2-03 6634 1530 www.burgerking.com.sg King app, Deliveroo and FoodPanda https://www.facebook.com/bus Bushido MBLM GP #01-02 Closed 6634 8879 hidoasia/ Closed but delivery Cedele MBFC T3 #01-07 6443 8553 https://www.cedelemarket.com available via website .sg/ Cedele ORQ ST #B2-02 TBC 6423 4882 Chopsticks by ORQ ST#B2-04 Open 6534 9168 www.theasiankitchen.com.sg The Asian Kitchen Closed but delivery Copper Chimney MBFC T3 #02-06 9238 1272 www.copperchimney.com.sg available via website Crave MBLM #B2-63 Open - www.crave.com.sg MBFC T1 #01- Dimbulah Open - www.dimbulahcoffee.com 01A Dimbulah ORQ ST #01-10 Open - www.dimbulahcoffee.com Din Tai Fung MBLM #B2-05 Open 6634 7877 www.dintaifung.com.sg Erwin's Gastrobar MBLM GP#01-01 Open 6634 8715 www.erwins.com.sg Forbidden Duck MBLM GP #02-02 Open 6509 8767 www.forbiddenduck.sg Harry's Bar MBLM GP#01-03 Open 6634 6318 http://harrys.com.sg/ Hey Bo MBLM #B2-41 Open 6974 6209 www.heybo.sg https://m.facebook.com/Men- ya-KAIKO- 616389838505564/menu/?p_r Hokkaido Ramen ef=pa&refsrc=https%3A%2F% MBFC T3 #01-01 Open 6509 8150 Men-ya KAIKO 2Fm.facebook.com%2Fpg%2 FMen-ya-KAIKO- 616389838505564%2Fmenu %2F&_rdr Shops operating hours may vary due to exigencies. -

How Much Do Japanese Really Care About Food Origin? a Case of Beef Bowl Shop Koichi Yamaura Department of International Environm

How Much Do Japanese Really Care about Food Origin? A Case of Beef Bowl Shop Koichi Yamaura Department of International Environmental and Agricultural Science Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology [email protected] Hikaru Hanawa Peterson Department of Applied Economics University of Minnesota [email protected] Selected Poster prepared for presentation at the 2016 Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, July 31 – Aug. 2. Copyright 2016 by Koichi Yamaura and Hikaru Hanawa Peterson. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided this copyright notice appears on all such copies. How Much Do Japanese Really Care about Food Origin? A Case of Beef Bowl Shop Koichi Yamaura*1 and Hikaru Hanawa Peterson2 1Assistant Professor, Dept. of International Environmental & Agricultural Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture & Technology. [email protected] 2 Professor, Dept. of Applied Economics, University of Minnesota. [email protected] Problem Identification Objectives Results Gyudon, or beef bowl, is one of Japanese popular fast foods Examines the preferences of Japanese consumers toward food Latent Class model & WTP results Table 3. Latent Class model results for Beef Bowl consisting of a bowl of rice topped with beef and onion origins including beef, after the 3.11 Earthquake and the Meal Ingredients Class Probability Model Meal Ingredients focused focused focused focused simmered in a mildly sweet sauce flavored with soy sauce and Fukushima nuclear disaster and resumption of U.S. beef trade. PRICE -0.0198 *** -0.0119 ** FEMALE -1.2522 *** -- (0.0010) (0.0052) (0.2092) other seasoning. -

Franchised Fast Food Brands: an Empirical Study of Factors Influencing Growth

Acta Commercii - Independent Research Journal in the Management Sciences ISSN: (Online) 1684-1999, (Print) 2413-1903 Page 1 of 8 Original Research Franchised fast food brands: An empirical study of factors influencing growth Authors: Orientation: Franchising is a popular and multifaceted business arrangement that captures a 1 Christopher A. Wingrove sizeable portion of the restaurant industry worldwide. Boris Urban1 Research purpose: The study empirically investigated the influence of various site location Affiliations: and branding factors on the growth of franchised fast food restaurant brands across the greater 1Graduate School of Business Administration, University of Gauteng region. the Witwatersrand, South Africa Motivation of the study: Researching which factors influence the growth of franchised fast food restaurant brands is important for an emerging market context such as South Africa when Corresponding author: considering the marked increase in the consumption of fast foods. Boris Urban, [email protected] Design: A sample of 140 customers was surveyed from 12 leading franchised fast food outlets. Primary data were collected for various items representing site location and brand factors. Dates: Received: 01 Aug. 2016 Regression analysis was used to test the hypotheses. Accepted: 04 Dec. 2016 Findings: The overall findings showed that convenience and central facilities of a retail Published: 31 Mar. 2017 location are positively and significantly associated with the growth of the franchise fast food How to cite this article: outlet. Wingrove, C.A. & Urban, B., 2017, ‘Franchised fast food Practical implications: The study findings have implications for practitioners who need to brands: An empirical study of take into account which factors influence revenue growth, since targeted interventions may be factors influencing growth’, required to implement sustainable strategies by franchisors. -

Hi! Guess the Restaurant Answers

33. Ruby Tuesday 75. Gringo’s 116. Al Baik 34. Zaxby’s 76. Krispy Kreme 117. Jreck Subs 35. Bob Evans 77. Mighty Taco 118. Max Burgers 36. New York Fries 78. Beefaroo 119. Pizza Express 37. Taco Time 79. Boston Market 120. Telepizza Hi! Guess The Restaurant 38. Red Robin 80. El Pollo Loco 121. Mr Hero Answers 39. BJ’s Brewhouse 81. Jason’s Deli 122. Rasika - Man Zhang 40. Whataburger 82. O’Charley’s 123. The Pita Pit 41. Quick 83. White Castle Main Game 42. Waffle House 84. Brodie’s Pub Fast Food 1. Pizza Hut 43. Johnny Rockets 85. Bonefish Grill 1. Hard Rock Café 2. Subway 44. Del Taco 86. Café Rio 2. Haägen Dazs 3. Starbucks 45. Nandos 87. Cici’s Pizza 3. Auntie Annes 4. Burger King 46. Quizno’s 88. Cook Out 4. Chicken Hut 5. Wendy’s 47. Steak n Shake 89. El Toro 5. Blimpie 6. Taco Bell 48. Church’s Chicken 90. Freddy’s 6. Big Bite 7. McDonalds 49. Fatburger 91. Sonic Drive-In 7. Mambo 8. Applebee’s 50. Bojangles 92. Qdoba 8. Outback 9. Chipotle 51. Round Table 93. Local Burger 9. Lone Star 10. Chick-Fil-A 52. Texas Roadhouse 94. Famous Dave’s 10. Best Italian 11. Denny’s 53. The Mad Greek 95. Tim Horton’s 11. The Keg 12. Dunkin Donuts 54. Carrabbas 96. IHOP 12. Dog Haus 13. Five Guys 55. Chili’s 97. Purple Cow 13. Carrows 14. Dominos Pizza 56. Rally’s 98. Ruth’s Chris 14. Galeto’s 15. -

Burger Brawl It’S Hard to Tear Yourself Away from the Lure of a Good Burger, Even Though You Know You Should Enjoy Them in Moderation

MALEGRA M S • NUTRITIO N MALEGRA M S • NUTRITIO N f o o d f i g h t Burger Brawl IT’S HARD TO TEAR YOURSELF AWAY FROM THE LURE OF A GOOD BURGER, EVEN THOUGH YOU KNOW YOU SHOULD ENJOY THEM IN MODERATION. BUT if YOU’RE A DIEHARD FAN OF THE GREASY (ALBEIT YUMMIER) SIDE OF LifE, WE PUT SOME SIGNATURE BURGERS TO THE TEST TO fiND OUT WHICH ONE SLAPS A LITTLE LESS GUILT ON THAT EXPANDING WAISTLINE. Round one: fat Burger King’s Hard Rock Café MacDonald’s KFC Zinger Carls Junior’s Dan Ryan’s Swensen’s Mos Burger’s Whopper Junior Pig Sandwich Big Mac Fat 30.3 g Famous Star Burger Mushroom Yakiniku Rice Fat 22.3 g Fat 41 g Fat 30 g Burger Fat 28 g Chicken Burger Burger Fat 32 g Fat 55 g Fat 27 g Round two: Calories BK Whopper Junior KFC Zinger Dan Ryan’s Burger Mos Burger’s Yakiniku Rice Burger 420 calories 517 calories 690 calories 510 calories Round thRee: Protein And the Burger Baron is… BK whopper Junior BK Whopper Junior Mos Burger’s Yakiniku Rice Burger Protein 18 g Protein 16 g ASK THE Several studies have shown that Q: I READ THAT TAkiNG beneficial. Omega-6 fatty acids in DIETITIAN citrus fruit peels, white pith and EssENTIAL FATTY Acids wiLL safflower, soybean, corn, or can- Thomas Teh pulps contain phytonutrients and HELP wiTH my EczEMA prOBLEM. ola oils are called Linoleic Acid dietary fibre. Phytonutrients may HOW DO THEY HELP ME? (LA), which are converted to GLA reduce blood pressure and inflam- in the body. -

Hotel Restaurant Institutional Korea

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 3/17/2014 GAIN Report Number: KS1415 Korea - Republic of Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional Biennial Report Approved By: Kevin Sage-EL, ATO Seoul Director Prepared By: Sangyong Oh, Marketing Specialist Report Highlights: The Hotel, Restaurant and Institutional (HRI) foodservice sector in South Korea continues to grow as on-going socio-economic changes promote increased consumer spending on dining outside of the home. Cash-register sales for the sector totaled W77.3 trillion won ($70.3 billion) in 2012, up 3 percent from the previous year. At the same time, the sector continues to restructure as large-scale restaurant companies as well as broad-line foodservice distributors expand at the expense of small-scale, independent businesses. As a result, the sector generates additional demand for products of new taste, added value, stable supply, consistent quality and specifications catered to the industry. These changes, coupled with implementation of the Korea-United States Free Trade Agreement, offer new export opportunities to a wide variety of American Products. Post: Seoul ATO Author Defined: Table of Contents SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY A. Overview of the Korean HRI Foodservice Sector B. Advantages and Challenges for U.S. Exports to the Korean Foodservice Sector SECTION II. ROADMAP FOR MARKET ENTRY A. Entry Strategy A-1. Food Trends in Korea A-2. Suggested Market Entry Tools B. Market Structure: Distribution Channel B-1. Product Flow B-2. Product Distribution to Independent, Small-scale Restaurants and Bars B-3. -

HO CHI MINH CITY Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

HO CHI MINH CITY Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | Ho Chi Minh City | 2019 0 Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) formerly known as Saigon, is the largest city in Vietnam with a total population of 8.6 million people (as of 2018). The city is Vietnam’s economic center, accounting for a large proportion of the national economy. In 2018, the city contributed nearly a quarter (or 24%) of the national total GDP. HCMC’s 2016 GDP per capita (the highest in Vietnam) was estimated at US$7,000 – as much as twice the national GDP per capita (US$2,340). HCMC has seen the strongest retail property performance in Vietnam. The total retail supply across shopping centers, department stores and retail podiums in the city is estimated at 1,340,000 sqm in net leasable area. The city is often the first point of entry for retailers new to Vietnam, due to its young, dynamic economy and also the lifestyle of its citizens. Many international brands started in Ho Chi Minh City including Gucci, Zara, H&M, Hermes, Bottega Veneta, Max & Co, Dorothy Perkins, Humphrey, F&F, Coach, Penshoppe and Under Amour among others. Additionally, an increasing number of retailers are looking to enter the market in the near future. HCMC is a multinational city with a diverse food and beverage offer. In the prime CBD (central business district), it is very convenient to locate a Western, Chinese, Korean or Japanese restaurant. Traditional local cuisine is also in abundance whether in low-cost single dish style street kitchens or more upmarket authentic restaurants.