British Attitudes Towards German Prisoners Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grizedale Forest

FORESTRY COMMISSION H.M. Forestry Commission GRIZEDALE FOREST FOR REFERENCE ONLY NWCE)CONSERVANCY Forestry Commission ARCHIVE LIBRARY 1 I.F.No: H.M. Forestry Commission f FORESTRY COMMISSION HISTORY o f SHIZEDALE FOREST 1936 - 1951 NORTH WEST (ENGLAND) CONSERVANCY HISTORY OF GRIZEDALE FOREST Contents Page GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE FOREST ...................... 1 Situation ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• 1 Ax*ea ancL Utilisation • • • ••• ••• ••• • • • 1 Physiography * *. ••• ... ••• ••• 4 Geology and Soils ... ... ... ... ... 5 Vegetation ... ... ... ... ••• 6 Meteorology ... •.• ••• ••• 6 Risks ••• • • • ••• ... ••• 7 Roads * • # ••• • • • ••• ••• 8 Labour .«• .«• ... .•• ••• 8 SILVICULTURE ••• * • • ••• ••• ••• 3 Preparation of Ground ... ... ... ... ... 3 t Choice of Species ... ... ... ... ... 9 Planting - spacing, types of plants used, Grizedale forest nursery, method of planting, annual rate of planting, manuring, success of establishment ... 11 Ploughing ... ... ... ... ... 13 Beating up ... ... ... ... ... li^ Weeding ... ... ... ... ... 14 Mixture of Species ... ... ... ... ... 14 Rates of Growth ... ... ... ... ... 13 Past treatment of established plantations Brashing, pruning, cleaning and thinning ... 17 Research ... ... ... ... ... 21 Conclusions ... ... ... ... ... 21 Notes by State Forests Officer ... ... ... ... 23 APPENDICES I Notes from Inspection Reports ... ... 24 II Record of Supervisory Staff ... ... 26 III Other notes of interest 1) Coppice demonstration area ... ... 27 2) Headquarters seed store ... ... 27 Map of the Forest HISTORY OF GRIZEDALE FOREST GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE FOREST Situation The forest is situated in the Furness Fells area of Lancashire between the waters of Coniston and Esthwaite. It lies within the Lake District National Park area, and covers a total of 5,807 acres. The name Grizedale is derived from the name given to the valley by the Norse invaders, who in the ninth century, colonised Furness and its Fells. At the heads of the high valleys, the then wild forest land was used for the keeping of pigs. -

From Periphery to Centre

CARE FROM PERIPHERY TO CENTRE Elena Cologni in collaboration with Homerton College, University of Cambridge This publication can be found in digital format, and printed in a limited edition of 100, including the print RELATIONS of CARE by Elena Cologni December 2020 © the authors and 250Homerton College Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 8PH Email: [email protected] Telephone: 01223 747069 https://homerton250.org/events/care-from-periphery-to-centre/ Homerton College is a Registered Charity No. 1137497 On the cover: detail of still from ‘THE NEW SCHOOL’ FILM, 1944. One of several surviving stills from a Crown Film Unit short information film shot at Homerton in 1944. CARE FROM PERIPHERY TO CENTRE Elena Cologni in collaboration with Homerton College, University of Cambridge 3 Page 3 Page CARE: FROM PERIPHERY TO CENTRE Elena Cologni’s artistic research looks at undervalued practices of care in society through people’s experiences of place. For this project, she collaborated with the 250 Archive Working Group in 2018 to respond to domestic, social and political dimensions of care in the work of Maud Cloudesley Brereton and Leah Manning, while researching the College’s archive and its architecture. The research was underpinned care ethics principles and a conversation with renowned care ethicist Virginia Held. A more intimate dimension is revealed through the selection of students’ items, as a snapshot of everyday life in an early 20th-century women’s College. This research unearths the College’s historic concern with, and contribution to, health, well-being and education. ELENA COLOGNI The exhibits resonate with Cologni’s aesthetic sensibility for their tactile and visual qualities, and underpin the artist’s sculptural installation designed in response to the 1914 Ibberson Gymnasium, and echoed in the Queen’s Wing veranda and lawn. -

British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 William Styles Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge September 2016 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy William Styles British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 This thesis is concerned with an analysis of British governmental attitudes and responses to communism in the United Kingdom during the early years of the Cold War, from the election of the Attlee government in July 1945 up until the election of the Wilson government in October 1964. Until recently the topic has been difficult to assess accurately, due to the scarcity of available original source material. However, as a result of multiple declassifications of both Cabinet Office and Security Service files over the past five years it is now possible to analyse the subject in greater depth and detail than had been previously feasible. The work is predominantly concerned with four key areas: firstly, why domestic communism continued to be viewed as a significant threat by successive governments – even despite both the ideology’s relatively limited popular support amongst the general public and Whitehall’s realisation that the Communist Party of Great Britain presented little by way of a direct challenge to British political stability. Secondly, how Whitehall’s understanding of the nature and severity of the threat posed by British communism developed between the late 1940s and early ‘60s, from a problem considered mainly of importance only to civil service security practices to one which directly impacted upon the conduct of educational policy and labour relations. -

Relating to Leah Manning

Hull History Centre: Papers and photographs relating to Leah Manning U DX265 Papers and photographs [1931-1991] relating to Leah Manning Accession number: 1993/18 Biographical Background: Born Elizabeth Leah Perrett on 14 April 1886. When she was 14 her parents migrated to Canada but she decided to remain in the UK with her grandparents. She attended Homerton College, Cambridge and was working as a teacher in Cambridge when she met Hugh Dalton and joined the Fabian Society and the Independent Labour Party. She campaigned for free milk for the school children to improve their health. In 1914 she married the astronomer William Henry Manning. Manning joined the 1917 club after the Russian Revolution and became a speaker at Labour events around the country. She became headmistress of an Open Air School for under- nourished children in Cambridge. In 1929 she was organising secretary of the National Union of Teachers and became President the following year. In February 1931 she was elected as MP for Islington East, only to lose her seat in the General Election when she decided not to support Ramsay Macdonald's National Government. She spent a year on the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party and stood as a candidate for Sunderland at the 1935 General Election but was unsuccessful. She also began to move away from her previous stance as a pacifist to that of actively campaigning against fascism. At the 1936 Labour party conference she argued, along with Ellen Wilkinson and Aneurin Bevan, for military assistance to be given to the Popular Front of Spain in its fight against Franco. -

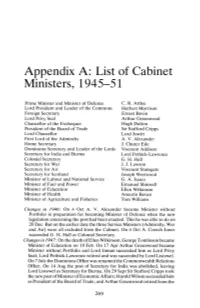

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51 Prime Minister and Minister of Defence C. R. Attlee Lord President and Leader of the Commons Herbert Morrison Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin Lord Privy Seal Arthur Greenwood Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton President of the Board of Trade Sir Stafford Cripps Lord Chancellor Lord Jowitt First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander Home Secretary J. Chuter Ede Dominions Secretary and Leader of the Lords Viscount Addison Secretary for India and Burma Lord Pethick-Lawrence Colonial Secretary G. H. Hall Secretary for War J. J. Lawson Secretary for Air Viscount Stansgate Secretary for Scotland Joseph Westwood Minister of Labour and National Service G. A. Isaacs Minister of Fuel and Power Emanuel Shinwell Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries Tom Williams Changes in 1946: On 4 Oct A. V. Alexander became Minister without Portfolio in preparation for becoming Minister of Defence when the new legislation concerning the post had been enacted. This he was able to do on 20 Dec. But on the earlier date the three Service Ministers (Admiralty, War and Air) were all excluded from the Cabinet. On 4 Oct A. Creech Jones succeeded G. H. Hall as Colonial Secretary. Changes in 1947: On the death of Ellen Wilkinson, George Tomlinson became Minister of Education on 10 Feb. On 17 Apr Arthur Greenwood became Minister without Portfolio and Lord Inman succeeded him as Lord Privy Seal; Lord Pethick-Lawrence retired and was succeeded by Lord Listowel. On 7 July the Dominions Office was renamed the Commonwealth Relations Office. -

The One Who (Almost) Got Away

The One who (Almost) Got Away. Leutnant Heinz Schnabel, 1/JG3. Most people are familiar with the story of Franz von Werra, the Luftwaffe pilot who was the only German to escape from captivity in the West, and return to Germany to continue his service. His story has been well documented, in books, magazines, and in a movie, entitled ‘The one that got away’ , starring Hardy Kruger as von Werra. Perhaps not so well known is the story of another Luftwaffe ‘ace’, Leutnant Heinz Schnabel who, together with Oberleutnant Harry Wappler, carried out an audacious escape attempt which very nearly succeeded. Heinz Schnabel was a 29 year old fighter pilot with the First Staffel, of 1 Gruppe, Jagdgeschwader 3 (1/JG3), equipped with the Messerschmitt Bf109E, and based at Colombert, due east of Boulogne, France, in September 1940. He had already gained ‘ace’ status, by shooting down three R.A.F. Blenheims during the Battle of France, and three Spitfires, the most recent being on 28 th August, but not without cost. During an air battle over France earlier in the year, he had sustained a bullet wound in the lungs and, semi-conscious, force-landed his ‘Emil’. With this wound not completely healed, it transpired that he would never regain full health, but he eventually rejoined his unit to continue flying and fighting. On the morning of 5th September, at the height of the Battle of Britain, JG3 were tasked, along with other units, with escorting a force of Heinkel He111 and Dornier Do17 bombers on a raid against England. -

Holidays for Working People C.1919-2000? the Competing Demands of Altruism and Commercial Necessity in the Co-Operative Holidays Association and Holiday Fellowship

Hope, Douglas G. (2015) Whatever happened to 'rational' holidays for working people c.1919-2000? The competing demands of altruism and commercial necessity in the Co-operative Holidays Association and Holiday Fellowship. Doctoral thesis, University of Cumbria (awarded by Lancaster University). Downloaded from: http://insight.cumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/1770/ Usage of any items from the University of Cumbria’s institutional repository ‘Insight’ must conform to the following fair usage guidelines. Any item and its associated metadata held in the University of Cumbria’s institutional repository Insight (unless stated otherwise on the metadata record) may be copied, displayed or performed, and stored in line with the JISC fair dealing guidelines (available here) for educational and not-for-profit activities provided that • the authors, title and full bibliographic details of the item are cited clearly when any part of the work is referred to verbally or in the written form • a hyperlink/URL to the original Insight record of that item is included in any citations of the work • the content is not changed in any way • all files required for usage of the item are kept together with the main item file. You may not • sell any part of an item • refer to any part of an item without citation • amend any item or contextualise it in a way that will impugn the creator’s reputation • remove or alter the copyright statement on an item. The full policy can be found here. Alternatively contact the University of Cumbria Repository Editor by emailing [email protected]. -

Ingham, Mary. 2019. 'Improperly and Amorously Consorting'

Ingham, Mary. 2019. ’Improperly and amorously consorting’: post-1945 relationships between British women and German prisoners of war held in the UK. Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis] http://research.gold.ac.uk/26281/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] ‘Improperly and amorously consorting’: post-1945 relationships between British women and German Prisoners of War held in the UK Mary Ingham Thesis submitted for examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of History, Goldsmiths College, University of London March 2019 Declaration of Authorship I, Mary Ingham, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. 6 March 2019 2 Acknowledgements This study would not exist without the generous response of all the women and men who shared their personal memories with a stranger. I am greatly indebted to them and to their families. I also owe a large debt of gratitude to Heidi Berry, and latterly to Ingrid Rock, for their invaluable translation assistance. I must also thank Sally Alexander for encouraging the proposal, my supervisor Richard Grayson for his support and guidance through this process, and others who have offered constructive suggestions. -

There's a Valley in Spain Called Jarama

There's a valley in Spain called Jarama The development of the commemoration of the British volunteers of the International Brigades and its influences D.G. Tuik Studentno. 1165704 Oudendijk 7 2641 MK Pijnacker Tel.: 015-3698897 / 06-53888115 Email: [email protected] MA Thesis Specialization: Political Culture and National Identities Leiden University ECTS: 30 Supervisor: Dhr Dr. B.S. v.d. Steen 27-06-2016 Image frontpage: photograph taken by South African photographer Vera Elkan, showing four British volunteers of the International Brigades in front of their 'camp', possibly near Albacete. Imperial War Museums, London, Collection Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. 1 Contents Introduction : 3 Chapter One – The Spanish Civil War : 11 1.1. Historical background – The International Brigades : 12 1.2. Historical background – The British volunteers : 14 1.3. Remembering during the Spanish Civil War : 20 1.3.1. Personal accounts : 20 1.3.2. Monuments and memorial services : 25 1.4. Conclusion : 26 Chapter Two – The Second World War, Cold War and Détente : 28 2.1. Historical background – The Second World War : 29 2.2. Historical background – From Cold War to détente : 32 2.3. Remembering between 1939 and 1975 : 36 2.3.1. Personal accounts : 36 2.3.2. Monuments and memorial services : 40 2.4. Conclusion : 41 Chapter Three – Commemoration after Franco : 43 3.1. Historical background – Spain and its path to democracy : 45 3.1.1. The position of the International Brigades in Spain : 46 3.2. Historical background – Developments in Britain : 48 3.2.1. Decline of the Communist Party of Great Britain : 49 3.2.2. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details The Island Race: geopolitics and identity in British foreign policy discourse since 1949 Nicholas Whittaker A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (International Relations) at the University of Sussex January 2016 Supervisors: Doctor Stefanie Ortmann and Doctor Fabio Petito I hereby declare that this thesis has not and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Nicholas Whittaker January 11 2016 abstract of thesis The Island Race: geopolitics and identity in British foreign policy discourse since 1949 This thesis examines Britain’s foreign policy identity by analysing the use of geopolitical tropes in discursive practices of ontological security-seeking in the British House of Commons since 1949, a period of great change for Britain as it lost its empire and joined NATO and the EC. The Empire was narrated according to a series of geopolitical tropes that I call Island Race identity: insularity from Europe and a universal aspect on world affairs, maintenance of Lines of Communication, antipathy towards Land Powers and the Greater Britain metacommunity. -

Steven Fielding

fielding jkt 10/10/03 2:18 PM Page 1 The Volume 1 Labour andculturalchange The LabourGovernments1964–1970 The Volume 1 Labour Governments Labour Governments 1964–1970 1964–1970 This book is the first in the new three volume set The Labour Governments 1964–70 and concentrates on Britain’s domestic policy during Harold Wilson’s tenure as Prime Minister. In particular the book deals with how the Labour government and Labour party as a whole tried to come to Labour terms with the 1960s cultural revolution. It is grounded in Volume 2 original research that uniquely takes account of responses from Labour’s grass roots and from Wilson’s ministerial colleagues, to construct a total history of the party at this and cultural critical moment in history. Steven Fielding situates Labour in its wider cultural context and focuses on how the party approached issues such as change the apparent transformation of the class structure, the changing place of women, rising black immigration, the widening generation gap and increasing calls for direct participation in politics. The book will be of interest to all those concerned with the Steven Fielding development of contemporary British politics and society as well as those researching the 1960s. Together with the other books in the series, on international policy and Fielding economic policy, it provides an unrivalled insight into the development of Britain under Harold Wilson’s premiership. Steven Fielding is a Professor in the School of Politics and Downloaded frommanchesterhive.comat09/30/202110:47:31PM Contemporary History at the University of Salford Steven Fielding-9781526137791 MANCHESTER via freeaccess MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS THE LABOUR GOVERNMENTS 1964–70 volume 1 Steven Fielding - 9781526137791 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/30/2021 10:47:31PM via free access fielding prelims.P65 1 10/10/03, 12:29 THE LABOUR GOVERNMENTS 1964–70 Series editors Steven Fielding and John W. -

Educating and Mobilizing the New Voter: Interwar Handbooks and Female Citizenship in Great- Britain, 1918-1931 Véronique Molinari

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 2 Jan-2014 Educating and Mobilizing the New Voter: Interwar Handbooks and Female Citizenship in Great- Britain, 1918-1931 Véronique Molinari Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Molinari, Véronique (2014). Educating and Mobilizing the New Voter: Interwar Handbooks and Female Citizenship in Great-Britain, 1918-1931. Journal of International Women's Studies, 15(1), 17-34. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol15/iss1/2 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2014 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Educating and Mobilizing the New Voter: Interwar Handbooks and Female Citizenship in Great-Britain, 1918-1931 By Véronique Molinari1 Abstract British women’s access to the electorate in 1918 and 1928 triggered off a series of efforts to reach out to the new voters both on the part of political parties and of women’s groups. New organisations were created, the role of women’s sections within political parties was reassessed and a wealth of propaganda material was published at election times that specifically targeted women. While some of these efforts were avowedly aimed at mobilizing the female vote in favour of a political party or around an ideological (feminist) agenda, others were seemingly simply intended to arouse women’s interest in politics and educate them in their new citizenship.