Cracking the Stonewall Norman Simms La Salle University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Follow in Lincoln's Footsteps in Virginia

FOLLOW IN LINCOLN’S FOOTSTEPS IN VIRGINIA A 5 Day tour of Virginia that follows in Lincoln’s footsteps as he traveled through Central Virginia. Day One • Begin your journey at the Winchester-Frederick County Visitor Center housing the Civil War Orientation Center for the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Become familiar with the onsite interpretations that walk visitors through the stages of the local battles. • Travel to Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters. Located in a quiet residential area, this Victorian house is where Jackson spent the winter of 1861-62 and planned his famous Valley Campaign. • Enjoy lunch at The Wayside Inn – serving travelers since 1797, meals are served in eight antique filled rooms and feature authentic Colonial favorites. During the Civil War, soldiers from both the North and South frequented the Wayside Inn in search of refuge and friendship. Serving both sides in this devastating conflict, the Inn offered comfort to all who came and thus was spared the ravages of the war, even though Stonewall Jackson’s famous Valley Campaign swept past only a few miles away. • Tour Belle Grove Plantation. Civil War activity here culminated in the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864 when Gen. Sheridan’s counterattack ended the Valley Campaign in favor of the Northern forces. The mansion served as Union headquarters. • Continue to Lexington where we’ll overnight and enjoy dinner in a local restaurant. Day Two • Meet our guide in Lexington and tour the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). The VMI Museum presents a history of the Institute and the nation as told through the lives and services of VMI Alumni and faculty. -

1 Powell, William H. the Fifth Army Corps (Army of the Potomac): A

Powell, William H. The Fifth Army Corps (Army of the Potomac): A Record of Operations during the Civil War in the United States of America, 1861-1865. London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1896. I. On the Banks of the Potomac— Organization— Movement to the Peninsula — Siege of Yorktown ... 1 Bull Run, Fitz John Porter, regiments, brigades, 1-19 Winter 1861-62, 22-23 Peninsula campaign, 24-27 Yorktown, corps organization, McClellan, Lincoln, officers, 27-58 II. Position on the Chickahominy — Battles of Hanover Court-House, Mechanicsville, and Gaines' Mill . 59 James River as a base, 59 Chickahominy, 59ff Hanover Courthouse, 63-74 Mechanicsville, 74-83 Gaines’s Mill, casualties, adjutants general, 83-123 III. The Change of Base— Glendale, or New Market Cross-Roads— Malvern Hill . 124 Change of Base, 124-30 White Oak Swamp, Savage Station, 130-37 Glendale, New Market, casualties, 137-50 Malvern Hill, casualties, 150-80 Corps organization, casualties, 183-87 IV. From the James to the Potomac — The Campaign in Northern Virginia — Second Battle of Bull Run . .188 Camp on James, McClellan order, reinforcements, Halleck, withdrawal order, 188-93 Second Bull Run campaign, 193-98 Second Bull Run, Pope, McDowell, McClellan, Porter, Fifth Corps casualties, 198-245 V. The Maryland Campaign— Battles of South Mountain — Antietam — Shepherdstown Ford 246 McClellan and Pope, Porter, 248-58 Maryland campaign, 258ff South Mountain, 266-68 Antietam, Hooker, 268-93 Shepherdstown, 293-303 Fifth Corps organization, casualties, 303-6 VI. The March from Antietam to Warrenton —General McClellan Relieved from Command — General Porter's Trial by Court-Martial 307 Army of the Potomac march to Warrenton, 307-13 Snicker’s Ferry, 313-16 Removal of McClellan, 316-22 Porter court martial, 322-51 1 VII. -

West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Twenty-Year Index, Volume 1-Volume 20, Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Anna M

West Virginia & Regional History Center University Libraries Newsletters 2012 West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Twenty-Year Index, Volume 1-Volume 20, Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Anna M. Schein Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvrhc-newsletters Part of the History Commons West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Twenty-Year Index Volume 1-Volume 20 Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Compiled by Anna M. Schein Morgantown, WV West Virginia and Regional History Collection West Virginia University Libraries 2012 1 Compiler’s Notes: Scope Note: This index includes articles and photographs only; listings of WVRHC staff, WVU Libraries Visiting Committee members, and selected new accessions have not been indexed. Publication and numbering notes: Vol. 12-v. 13, no. 1 not published. Issues for summer 1985 and fall 1985 lack volume numbering and are called: no. 2 and no.3 respectively. Citation Key: The volume designation ,“v.”, and the issue designation, “no.”, which appear on each issue of the Newsletter have been omitted from the index. 5:2(1989:summer)9 For issues which have a volume number and an issue number, the volume number appears to left of colon; the issue number appears to right of colon; the date of the issue appears in parentheses with the year separated from the season by a colon); the issue page number(s) appear to the right of the date of the issue. 2(1985:summer)1 For issues which lack volume numbering, the issue number appears alone to the left of the date of the issue. Abbreviations: COMER= College of Mineral and Energy Resources, West Virginia University HRS=Historical Records Survey US=United States WV=West Virginia WVRHC=West Virginia and Regional History Collection, West Virginia University Libraries WVU=West Virginia University 2 West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Index Volume 1-Volume 20 Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Compiled by Anna M. -

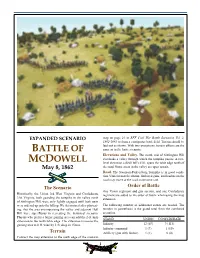

Battle of Mcdowell Scenario Map with Extension

EXPANDED SCENARIO map on page 21 in RFF Civil War Battle Scenarios Vol. 2, 1862-1863 to form a contiguous battlefield. Terrain should be laid out as shown. With two exceptions, terrain effects are the BATTLE OF same as in the basic scenario. Elevations and Valley. The north end of Sittlington Hill overlooks a valley through which the turnpike passes. A two- MCDOWELL level elevation called Hull’s Hill, spans the table edge north of May 8, 1862 the road. Some areas in the valley are open terrain. Road. The Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike is in good condi- tion. Units in march column, limbered guns, and leaders on the road may move at the road movement rate. The Scenario Order of Battle One Union regiment and gun section, and one Confederate Historically, the Union 3rd West Virginia and Confederate regiment are added to the order of battle when using the map 31st Virginia, both guarding the turnpike in the valley north extension. of Sittlington Hill, were only lightly engaged until both units were ordered up onto the hilltop. We determined after playtest- The following number of additional stands are needed. The ing, that the area encompassing the valley and adjacent Hull number in parenthasis is the grand total from the combined Hill were superfluous to recreating the historical scenario. scenarios. Players who prefer a larger gaming area can add the 2-ft. map STAND UNION CONFEDERATE extension to the north table edge. The extension increases the gaming area to 8-ft. wide by 5-ft. deep in 15mm. Infantry 12 (69) 9 (113) Infantry command 1 (7) 1 (10) Terrain Artillery (gun with limber) 1 (1) 0 (0) Connect the map extension to the north edge of the scenario 1 1 pt Battle of McDowell Scenario Map with Extension N Johnson E W 8” and on a S 2-level elevation, C on turn 4. -

Fredericksburg/Stafford Battlefield Tour

Chatham Ennis House at Sunken Road llocate 4 1/2 hours for Fredericksburg, Stafford, Spotsylvania, Virginia this tour. Strategically located midway between the capital of the Con- Fredericksburg/Stafford Afederacy in Richmond and the U. S. capital in Washington, D. C., Fred- Battlefield Tour ericksburg was the scene of four of the most devastating battles of the Stop 1 Civil War. Nearly 110,000 casual- Lee had a close brush with death. At Fredericksburg Battlefield Visitor Cen- Lee’s command post atop Lee Hill, visi- ties occurred in the Battles of Fred- ter — See a film depicting the actions ericksburg, Chancellorsville, Wilder- tors can view the city and look at battle that took place in and around Freder- exhibits. ness and Spotsylvania Court House. icksburg. Museum exhibits portray a Stop 2 During the war, possession of the soldier’s life during the war, including Chatham — Chatham was an important city changed hands seven times. camp life, religious life, food, medicine, Federal headquarters and communica- amusements, uniforms and equipment, tion center during the Battle of Freder- transportation, communications, and icksburg. It was also a hospital where the impact of war on civilians. Also as Walt Whitman and Clara Barton assisted park staff is available, opt for a short the surgeons. Union artillery from this guided walk along Sunken Road. Here vicinity blasted the city to cover the en- Confederate troops, securely positioned gineers building the pontoon bridges. behind the famous stone wall, dis- Allow 45 minutes. patched more than 8,000 Union soldiers during the Battle of Fredericksburg. The Stop 3 walk includes dwellings standing during White Oak Museum — This Civil War the battle, a monument to the humani- museum houses an extensive collection tarian acts of a Confederate soldier, and of artifacts from actual battle sites and the National Cemetery where 15,000 encampments of the Civil War. -

Culp's Hill, Gettysburg, Battle of Gettysburg

Volume 3 Article 7 2013 Culp’s Hill: Key to Union Success at Gettysburg Ryan Donnelly Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/gcjcwe Part of the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Donnelly, Ryan (2013) "Culp’s Hill: Key to Union Success at Gettysburg," The Gettysburg College Journal of the Civil War Era: Vol. 3 , Article 7. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/gcjcwe/vol3/iss1/7 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Culp’s Hill: Key to Union Success at Gettysburg Abstract Brigadier General George S. Greene’s position on Culp’s Hill during the Battle of Gettysburg is arguably the crucial lynchpin of July 2, 1863. Had this position at the barb of the fishhook defensive line fallen, Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his army would then have been positioned to take Cemetery Hill, thus breaking the curve of the hook on the Union right. This most likely would have sent the Union into retreat, leaving the direct route to Washington unguarded. Fortunately, valiant efforts were made by men like Generals George S. Greene and Henry H. Lockwood in order to preserve the Union Army’s possession of the hill and, as a result, preserve the Union itself. While leaders distinguished themselves during the Battle of Gettysburg with exceptional decision-making and ingenuity, the battle for ulpC ’s Hill also embodied the personal cost these decisions made, as evidenced by the experience of Marylanders who literally fought their neighbors. -

PICKETT's CHARGE Gettysburg National Military Park STUDENT

PICKETT’S CHARGE I Gettysburg National Military Park STUDENT PROGRAM U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Pickett's Charge A Student Education Program at Gettysburg National Military Park TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 How To Use This Booklet ••••..••.••...• 3 Section 2 Program Overview . • . • . • . • . 4 Section 3 Field Trip Day Procedures • • • . • • • . 5 Section 4 Essential Background and Activities . 6 A Causes ofthe American Civil War ••..•...... 7 ft The Battle ofGettysburg . • • • . • . 10 A Pi.ckett's Charge Vocabulary •............... 14 A Name Tags ••.. ... ...........• . •......... 15 A Election ofOfficers and Insignia ......•..•.. 15 A Assignm~t ofSoldier Identity •..••......... 17 A Flag-Making ............................. 22 ft Drill of the Company (Your Class) ........... 23 Section 5 Additional Background and Activities .••.. 24 Structure ofthe Confederate Army .......... 25 Confederate Leaders at Gettysburg ••.•••.••• 27 History of the 28th Virginia Regiment ....... 30 History of the 57th Virginia Regiment . .. .... 32 Infantry Soldier Equipment ................ 34 Civil War Weaponry . · · · · · · 35 Pre-Vtsit Discussion Questions . • . 37 11:me Line . 38 ... Section 6 B us A ct1vities ........................• 39 Soldier Pastimes . 39 Pickett's Charge Matching . ••.......•....... 43 Pickett's Charge Matching - Answer Key . 44 •• A .•. Section 7 P ost-V 1s1t ctivities .................... 45 Post-Visit Activity Ideas . • . • . • . • . 45 After Pickett's Charge . • • • • . • . 46 Key: ft = Essential Preparation for Trip 2 Section 1 How to Use This Booklet Your students will gain the most benefit from this program if they are prepared for their visit. The preparatory information and activities in this booklet are necessary because .. • students retain the most information when they are pre pared for the field trip, knowing what to expect, what is expected of them, and with some base of knowledge upon which the program ranger can build. -

Thomas Mays on Law's Alabama Brigade in the War Between the Union and the Confederacy

Morris Penny, J. Gary Laine. Law's Alabama Brigade in the War Between the Union and the Confederacy. Shippensburg, Penn: White Mane Publishing, 1997. xxi + 458 pp. $37.50, paper, ISBN 978-1-57249-024-6. Reviewed by Thomas D. Mays Published on H-CivWar (August, 1997) Anyone with an interest in the battle of Get‐ number of good maps that trace the path of each tysburg is familiar with the famous stand taken regiment in the fghting. The authors also spice on Little Round Top on the second day by Joshua the narrative with letters from home and interest‐ Chamberlain's 20th Maine. Chamberlain's men ing stories of individual actions in the feld and and Colonel Strong Vincent's Union brigade saved camp, including the story of a duel fought behind the left fank of the Union army and may have in‐ the lines during the siege of Suffolk. fluenced the outcome of the battle. While the leg‐ Laine and Penny begin with a very brief in‐ end of the defenders of Little Round Top contin‐ troduction to the service of Evander McIver Law ues to grow in movies and books, little has been and the regiments that would later make up the written about their opponents on that day, includ‐ brigade. Law, a graduate of the South Carolina ing Evander Law's Alabama Brigade. In the short Military Academy (now known as the Citadel), time the brigade existed (1863-1865), Law's Al‐ had been working as an instructor at a military abamians participated in some of the most des‐ prep school in Alabama when the war began. -

My Brave Texans, Forward and Take Those Heights!”1

“My brave Texans, forward and take those heights!”1 Jerome Bonaparte Robertson and the Texas Brigade Terry Latschar These words echoed through the battle line of the Texas brigade on July 2, 1863 on a ridge south of Gettysburg as Major General John Bell Hood ordered Brigadier General Jerome Robertson, commander of Hood’s famous Texas brigade, to lead his men into action. General Robertson then repeated those words with the authority and confidence needed to move his 1,400 men forward under artillery fire to engage the enemy on the rocky height 1,600 yards to their front. What kind of man could lead such a charge, and what kind of leader could inspire the aggressive Texans? Jerome Bonaparte Robertson was born March 14, 1815, in Christian County, Kentucky, to Cornelius and Clarissa Robertson. When Jerome was eight years old, his father passed away and left his mother penniless. One of five children, and the oldest son, Jerome quickly left his childhood behind. As was the custom of the time, he was apprenticed to a hatter. Five years later Jerome’s master moved to St. Louis, Missouri. After five more years of industrious and demanding labor, when he was eighteen, Jerome was able to buy the remainder of his contract. During his time in St. Louis, Jerome was befriended by Dr. W. Harris, who educated him in literary subjects. The doctor was so taken with Robertson that he helped Jerome return to Kentucky and attend Transylvania University. There Jerome studied medicine and, in three years, graduated as a doctor in 1835. -

Like Our Friends and Partners at the Civil War Trust, the Shenandoah Valley Chairman Battlefields Foundation (SVBF) Is Working Every Day to Preserve and Protect

“The Civil War Trust is thrilled that the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation is preserving key hallowed ground, such as these 23 acres at McDowell. This land, when added to what has already been saved there by our two organizations as well as others, will put us even closer to one of our main objectives: substantially completing this historic battlefield. We are so grateful for strong local preservation groups like SVBF, who are the crucial ‘boots on the ground.’ I encourage every American who cares about saving our nation’s history to support them to the fullest extent you can.” Jim Lighthizer, President Civil War Trust Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation BOARD OF TRUSTEES: Allen L. Louderback Like our friends and partners at the Civil War Trust, the Shenandoah Valley Chairman Battlefields Foundation (SVBF) is working every day to preserve and protect Nicholas P. Picerno battlefields and to tell the story of the American Civil War. Vice Chairman I’m writing today to ask you to join our fight in the Shenandoah Valley and help me Robert T. Mitchell, Jr. Secretary save 23 acres at the very center of the McDowell battlefield. The Battle of McDowell is the fight that set the stage for General Thomas J. “Stonewall" Jackson’s 1862 Brian K. Plum Treasurer successes in the Valley – the battle that Ed Bearss (a member and longtime supporter of our foundation) calls, “... the most important battle of Jackson’s masterful 1862 John P. Ackerly, III Valley campaign.” Childs F. Burden The parcel I need you to help me save is situated along the historic Staunton and Michael A. -

James Longstreet and His Staff of the First Corps

Papers of the 2017 Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar The Best Staff Officers in the Army- James Longstreet and His Staff of the First Corps Karlton Smith Lt. Gen. James Longstreet had the best staff in the Army of Northern Virginia and, arguably, the best staff on either side during the Civil War. This circumstance would help to make Longstreet the best corps commander on either side. A bold statement indeed, but simple to justify. James Longstreet had a discriminating eye for talent, was quick to recognize the abilities of a soldier and fellow officer in whom he could trust to complete their assigned duties, no matter the risk. It was his skill, and that of the officers he gathered around him, which made his command of the First Corps- HIS corps- significantly successful. The Confederate States Congress approved the organization of army corps in October 1862, the law approving that corps commanders were to hold the rank of lieutenant general. President Jefferson Davis General James Longstreet in 1862. requested that Gen. Robert E. Lee provide (Museum of the Confederacy) recommendations for the Confederate army’s lieutenant generals. Lee confined his remarks to his Army of Northern Virginia: “I can confidently recommend Generals Longstreet and Jackson in this army,” Lee responded, with no elaboration on Longstreet’s abilities. He did, however, add a few lines justifying his recommendation of Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson as a corps commander.1 When the promotion list was published, Longstreet ranked as the senior lieutenant general in the Confederate army with a date of rank of October 9, 1862. -

Civil War Battles, Campaigns, and Sieges

Union Victories 1862 February 6-16: Fort Henry and Fort Donelson Campaign (Tennessee) March 7-8: Battle of Pea Ridge (Arkansas) April 6-7: Battle of Shiloh/ Pittsburg Landing (Tennessee) April 24-27: Battle of New Orleans (Louisiana) September 17: Battle of Antietam/ Sharpsburg (Maryland) October 8: Battle of Perryville (Kentucky) December 31-January 2, 1863: Battle of Stone’s River/ Murfreesboro (Tennessee) 1863 March 29- July 4: Vicksburg Campaign and Siege (Mississippi)- turning point in the West July 1-3: Battle of Gettysburg (Pennsylvania)- turning point in the East November 23-25: Battle of Chattanooga (Tennessee) 1864 May 7-September 2: Atlanta Campaign (Georgia) June 15-April 2, 1865: Petersburg Campaign and Siege (Virginia) August 5: Battle of Mobile Bay (Alabama) October 19: Battle of Cedar Creek (Virginia) December 15-16: Battle of Nashville (Tennessee) November 14-December 22: Sherman’s March to the Sea (Georgia) 1865 March 19-21: Battle of Bentonville/ Carolinas Campaign (North Carolina) Confederate Victories 1861 April 12-14: Fort Sumter (South Carolina) July 21: First Battle of Manassas/ First Bull Run (Virginia) August 10: Battle of Wilson’s Creek (Missouri) 1862 March 17-July: Peninsula Campaign (Virginia) March 23-June 9: Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Virginia) June 25-July 2: Seven Days Battle (Virginia) August 28-30: Second Battle of Manassas/ Second Bull Run (Virginia) December 11-13: Battle of Fredericksburg (Virginia) 1863 May 1-4: Battle of Chancellorsville (Virginia) September 19-20: Battle of Chickamauga (Georgia)