Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Actor's Exploration of the Earl of Kent in William Shakespeare's

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research and Creative Activity in Theatre and Film Theatre and Film, Johnny Carson School of 5-2010 The Heroic Struggle of Pleasing a Mad King: An Actor’s Exploration of the Earl of Kent in William Shakespeare’s King Lear Robie A. Hayek University of Nebraska at Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/theaterstudent Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Hayek, Robie A., "The Heroic Struggle of Pleasing a Mad King: An Actor’s Exploration of the Earl of Kent in William Shakespeare’s King Lear" (2010). Student Research and Creative Activity in Theatre and Film. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/theaterstudent/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theatre and Film, Johnny Carson School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research and Creative Activity in Theatre and Film by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE HEROIC STRUGGLE OF PLEASING A MAD KING: AN ACTOR’S EXPLORATION OF THE EARL OF KENT IN WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S KING LEAR by Robie A. Hayek A THESIS Presented to the faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Major: Theatre Arts Under the Supervision of Professor Harris Smith Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 THE HEROIC STRUGGLE OF PLEASING A MAD KING: AN ACTOR’S EXPLORATION OF THE EARL OF KENT IN WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S KING LEAR Robie A. -

Cordelia''s Portrait in the Context of King Lear''s

Paula M. Rodríguez Gómez Cordelias Portrait in the Context of King Lears... 181 CORDELIAS PORTRAIT IN THE CONTEXT OF KING LEARS INDIVIDUATION* Paula M. Rodríguez Gómez** Abstract: This analysis attempts to show the relations between the individual psyche and the contents of the collective unconscious. Following Von Franzs analytical technique, the tragic action in King Lear will be read as an individuation process that will rescue archetypal contents and solve existential paradoxes that cause an imbalance between the ego and the self, leading to self-destruction. Once communication is eased and balance is restored, the transformation-seeking process that engaged the design of the play itself becomes resolved, and events can be led to a conventional tragic resolution. Jungian analysis will therefore provide a critical framework to unveil the subconscious contents that tear the character of the king between annihilation and survival, the anima complex that affects the king, responding thus for the action of the play and its centuries-old success. Keywords: collective unconscious, myth, individuation, archetype, tragedy, anima. Resumen: Este análisis pretende sacar a la luz las relaciones entre la psyche individual y los contenidos del inconsciente colectivo. Siguiendo la técnica analítica de Von Franz, la acción trágica de King Lear será entendida a través del proceso de individuación que revierte sobre los contenidos arquetípicos y resuelve las paradojas existenciales que cau- san el desequilibrio entre ego y self. Una vez que la comunicación es facilitada y el equilibrio psíquico recuperado, el proceso transformativo que afecta la génesis de la trama se resuelve y el argumento alcanza una resolución convencional. -

Teaching the Ending of King Lear

Teaching the ending of King Lear www.juliangirdham.com/king-lear INOTE, November 2020 “All’s cheerless, dark and deadly.” “It’s not the despair, Laura. I can stand the despair. It’s the hope.” Chiaroscuro Chiar oscuro Light / Dark ‘Redemptive’? (the comic and the Christian strain). ● Lear’s journey from blindness to empathy. He learns. His insights into society, the poor, ‘unaccommodated man’. Rebirth (resurrection) through suffering. ● A ‘Christian’ journey? ● Kent’s unwavering loyalty. ● The heroism of the servant who kills Cornwall. ● Cordelia’s love and the reunion with Lear. ● Gloucester’s journey towards ‘seeing’. His ‘smiling’ death. ● The deaths of all the malignant people: Cornwall, Regan, Goneril, Edmund. ● Lear’s consoling belief that Cordelia is alive at the end. ● Edgar’s journey from gullibility to heroism. ● Edgar as King. ‘Bleak’? (the tragic strain) ● Stupidity of the first scene. Division of the kingdom unleashes chaos. ● ‘Filial ingratitude’. ● Suffering, pain. ● The storm as a central metaphor. ● The relentless injustice. ● Lear’s breakdown; madness. ● Gloucester’s blinding. The horror of the actual scene. ● The dominance of Cornwall, Regan, Goneril, Edmund. ● The ineffectiveness of Albany, the Fool, Edgar, Kent. ● Gloucester’s death. ● The message that was sent too late. ● Cordelia’s death. ● Lear’s pathetically mistaken belief that she is alive. ● The lack of consolation at the end. The ending of King Lear James Shapiro (1) ‘For those at the court performance familiar with earlier versions of the story in which the king is restored to the throne and reconciled with his youngest daughter, this must have been shocking, the image and horror of the collapse of the state and the obliteration of the royal family akin to the violent fantasy of the Gunpowder plotters a year earlier.’ The ending of King Lear James Shapiro (2) 'Those in the audience who had seen King Leir or had read any of the other versions of Lear's reign in circulation already knew how the story ends .. -

Sources of Lear

Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Lynne Bradley, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) Abstract The temptation to meddle with Shakespeare has proven irresistible to playwrights since the Restoration and has inspired some of the most reviled and most respected works of theatre. Nahum Tate’s tragic-comic King Lear (1681) was described as an execrable piece of dementation, but played on London stages for one hundred and fifty years. David Garrick was equally tempted to adapt King Lear in the eighteenth century, as were the burlesque playwrights of the nineteenth. In the twentieth century, the meddling continued with works like King Lear’s Wife (1913) by Gordon Bottomley and Dead Letters (1910) by Maurice Baring. -

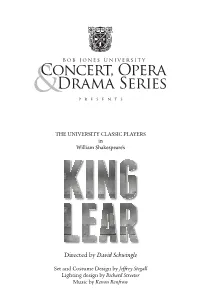

Directed by David Schwingle

THE UNIVERSITY CLASSIC PLAYERS in William Shakespeare’s Directed by David Schwingle Set and Costume Design by Jeffrey Stegall Lighting design by Richard Streeter Music by Kenon Renfrow CAST OF CHARACTERS DIRECTOR’S NOTES Lear, King of Britain ......................................................................... Ron Pyle It is a fearful thing to write about Shakespeare (brief let me be!). The fear increases when one approaches the Goneril, Lear’s eldest daughter ............................................................... Erin Naler towering achievement that is King Lear. The wheel turns a bit more toward a paralyzed state if one considers Duke of Albany, Goneril’s husband ................................................... Harrison Miller the laden, ceremonial barge of relevant scholarship on the subjects. (Imagine entering a room and seeing Oswald, Goneril’s steward ............................................................. Nathan Pittack the eminent Shakespeare scholar, Emma Smith, or our local Spenser and Shakespeare scholar, Ron Horton, Regan, Lear’s second daughter ............................................................ Emily Arcuri comfortably seated, smiling at you!) And yet, though surrounded by giants on every side, some of Lear’s own Duke of Cornwall, Regan’s husband ..................................................... Alex Viscioni making, King Lear pushes on, so I’ll push on and pen a few words about Lear, language, and love. Cordelia, Lear’s youngest daughter .................................................... -

Literature : King Lear ( Act (1

Literature : King Lear Act (1 ( Farhouda Ferwana Rula Farouq Al Farra Objectives: Students are expected to: Scan the 1st act for details, then answer comprehension questions. 2 A long time ago, Lear was King of Britain. He had three daughters. The oldest daughter, Goneril, was married to the Duke of Albany. His middle daughter, Regan, was the wife of the Duke of Cornwall. The King of France and the Duke of Burgundy both wanted to marry his youngest daughter, Cordelia. 3 A long time ago, Lear was King of Britain. He had three daughters. The oldest daughter, Goneril, was married to the Duke of Albany. His middle daughter, Regan, was the wife of the Duke of Cornwall. The King of France and the Duke of Burgundy both wanted to marry his youngest daughter, Cordelia. Answer the following question: 1. Who was Lear? How many daughters did he have? He was King of Britain and he had three daughters, Goneril, Regan and Cordelia. 4 King Lear was old and tired, and he decided to give the country to his three daughters. They and their husbands would rule instead of him, while he, with one hundred knights to protect him, would stay with each daughter in turn for a month. 5 King Lear was old and tired, and he decided to give the country to his three daughters. They and their husbands would rule instead of him, while he, with one hundred knights to protect him, would stay with each daughter in turn for a month. 2. What will happen when he gives them the country? a. -

MANY MOTIVES: GEOFFREY of MONMOUTH and the REASONS for HIS FALSIFICATION of HISTORY John J. Berthold History 489 April 23, 2012

MANY MOTIVES: GEOFFREY OF MONMOUTH AND THE REASONS FOR HIS FALSIFICATION OF HISTORY John J. Berthold History 489 April 23, 2012 i ABSTRACT This paper examines The History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth, with the aim of understanding his motivations for writing a false history and presenting it as genuine. It includes a brief overview of the political context of the book at the time during which it was first introduced to the public, in order to help readers unfamiliar with the era to understand how the book fit into the world of twelfth century England, and why it had the impact that it did. Following that is a brief summary of the book itself, and finally a summary of the secondary literature as it pertains to Geoffrey’s motivations. It concludes with the claim that all proposed motives are plausible, and may all have been true at various points in Geoffrey’s career, as the changing times may have forced him to promote the book for different reasons, and under different circumstances than he may have originally intended. Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. ii CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Who was Geoffrey of Monmouth? 3 Historical Context 4 The Book 6 Motivations 11 CONCLUSION 18 WORKS CITED 20 WORKS CONSULTED 22 1 Introduction Sometime between late 1135 and early 1139 Geoffrey of Monmouth released his greatest work, Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain in modern English). -

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER [p. iv] © Michael Alexander 2000 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W 1 P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 0-333-91397-3 hardcover ISBN 0-333-67226-7 paperback A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 O1 00 Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts Printed in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts [p. v] Contents Acknowledgements The harvest of literacy Preface Further reading Abbreviations 2 Middle English Literature: 1066-1500 Introduction The new writing Literary history Handwriting -

An Ecocritical and Performance History of King Lear. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017

Hamilton, Jennifer Mae. "Bibliography." This Contentious Storm: An Ecocritical and Performance History of King Lear. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 199–222. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 07:34 UTC. Copyright © Jennifer Hamilton 2017. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Bibliography Manuscripts, Archival Materials, Illustrations and Rare Publications A most true and Lamentable Report, of a great Tempest of haile which fell upon a Village in Kent, called Stockbery, about three myles from Cittingborne, the nineteenth day of June last past. 1590. Whereby was destroyed a great abundance of corn and fruite, to the impoverishing and undoing of divers men inhabiting within the same Village. Thomas Butter, London, 1590. Available at Early English Books Online, http://eebo.chadwyck.com (accessed 12 August 2011). Andersen, Hans Christian. Pictures of Travel: In Sweden amongst the Hartz Mountains, and in Switzerland, with a visit at Charles Dickens’s House. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1871. Barry, James. King Lear Weeping Over the Dead Body of Cordelia, c. 1776–8. Oil on Canvas, Tate Britain. Available online: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/barry- king-lear-weeping-over-the-dead-body-of-cordelia-t00556 (accessed 6 October 2010). Craig, Edward Gordon. The Storm in King Lear, 1920. Woodcut. Victoria and Albert Museum, E.1146–1924. Available online: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/ O766388/print-the-storm-in-king-lear/ (accessed 6 February 2012). -

![The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear As Inscriptive Site John Rempel](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3600/the-history-of-king-lear-1681-lear-as-inscriptive-site-john-rempel-1643600.webp)

The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear As Inscriptive Site John Rempel

Document generated on 09/29/2021 12:39 a.m. Lumen Selected Proceedings from the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies Travaux choisis de la Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site John Rempel Theatre of the world Théâtre du monde Volume 17, 1998 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1012380ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1012380ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle ISSN 1209-3696 (print) 1927-8284 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Rempel, J. (1998). Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site. Lumen, 17, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.7202/1012380ar Copyright © Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle, 1998 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 3. Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site From Addison in 1711 ('as it is reformed according to the chimerical notion of poetical justice, in my humble opinion it has lost half its beauty') to Michael Dobson in 1992 (Shakespeare 'serves for Tate .. -

1 King Lear, the Taming of the Shrew, a Midsummer Night's Dream, and Cymbeline, Presented by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Fe

King Lear, The Taming of the Shrew, A Midsummer Night's Dream, and Cymbeline, presented by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, February-November 2013. Geoff Ridden Southern Oregon University [email protected] King Lear. Director: Bill Rauch. With Jack Willis/Michael Winters (King Lear), Daisuke Tsuji (Fool), Sofia Jean Gomez (Cordelia), and Armando Durán (Kent). The Taming of the Shrew. Director: David Ivers. With Ted Deasy (Petruchio), Neil Geisslinger (Kate), John Tufts (Tranio), and Wayne T. Carr (Lucentio). Cymbeline. Director: Bill Rauch. With Daniel José Molina (Posthumus), Dawn-Lyen Gardner (Imogen), and Kenajuan Bentley (Iachimo). A Midsummer Night's Dream. Director: Christopher Liam Moore. With Gina Daniels (Puck), and Brent Hinkley (Bottom). This was the 78th season of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, and four of its eleven productions were Shakespeare plays: two were staged indoors (King Lear and The Taming of the Shrew) and two outdoors on the Elizabethan Stage/Allen Pavilion. This was the first season in which plays were performed indoors across the full season, and so both The Taming of the Shrew and King Lear had large numbers of performances. Nevertheless, according to the Mail Tribune, the non-Shakespeare plays drew larger audiences than Shakespeare this season: the plays staged outdoors fared especially poorly, and this is explained in part by the fact that four outdoor performances had to be cancelled because of 1 smoke in the valley, resulting in a loss of ticket income of around $200,000.1 King Lear King Lear was staged in the Thomas Theatre (previously the New Theatre), the smallest of the OSF theatres, and ran from February to November. -

Comparing the Daughters in King Lear and a Thousand Acres

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 5-4-2018 Reclaiming Independence: Comparing the Daughters in King Lear and A Thousand Acres Zachary Caldwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Caldwell, Zachary, "Reclaiming Independence: Comparing the Daughters in King Lear and A Thousand Acres" (2018). Student Research Submissions. 243. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/243 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Caldwell 1 Zachary Caldwell Dr. Mathur ENGL 491 4 May 2018 Reclaiming Independence: Comparing the Daughters in King Lear and A Thousand Acres In his book, Shakespeare and Modern Popular Culture, Douglas Lanier analyzes how authors adapt Shakespeare to the current era and provides some methods that authors use to do so. Jane Smiley adopts two of these methods of reoriented and interpolated narrative in her novel, A Thousand Acres, to shift William Shakespeare’s patriarchal play, King Lear, into a feminist text through the perspective and actions of the three daughters, Ginny, Rose, and Caroline. Lanier explains that a reoriented narrative is one “in which the narrative is told from a different point of view” (83). A Thousand Acres shifts from the point of view centralized around King Lear to the eldest daughter in the novel, Ginny. An interpolated narrative is one “in which new plot material is dovetailed with the plot of the source” (Lanier 83), meaning that some plot points are added, subtracted, and/or altered from the original text.