'It's Not That the Tories Are Closer in Winnipeg, 1945-1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board 61St Annual Report for the Year Ended March 31, 2012

Needs For and Alternatives To APPENDIX I Manitoba Hydro‐Electric Board 61st Annual Report This page is intentionally left blank. our focus Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board 61st Annual Report For the Year Ended March 31, 2012 AR_2012_cover.indd 1 12-07-11 1:24 PM CORPORATE PROFILE VISION CORPORATE GOALS Manitoba Hydro is one of the largest To be the best utility in North • Improve safety in the workplace. integrated electricity and natural gas America with respect to safety, rates, • Provide exceptional customer value. distribution utilities in Canada. We reliability, customer satisfaction and • Strengthen working relationships provide reliable, affordable energy to environmental leadership; and to with Aboriginal peoples. customers throughout Manitoba and always be considerate of the needs • Maintain financial strength. trade electricity within three wholesale of customers, employees • Extend and protect access to North markets in the Midwestern United and stakeholders. American energy markets and States and Canada. We are also a leader profitable export sales. in promoting conservation, providing MISSION • Attract, develop and retain a highly numerous Power Smart* programs to To provide for the continuance of a skilled and motivated workforce help our customers get supply of energy to meet the needs of that reflects the demographics of the most out of their energy. the province and to promote economy Manitoba. and efficiency in the development, • Protect the environment in everything Nearly all of the electricity Manitoba generation, transmission, distribution, that we do. Hydro produces each year is clean, supply and end-use of energy. • Promote cost effective energy renewable power generated using the conservation and innovation. -

Valid Operating Permits

Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality Region Number Facility 20525 WOODLANDS SHELL UST Woodlands Interlake 20532 TRAPPERS DOMO UST Alexander Eastern 55141 TRAPPERS DOMO AST Alexander Eastern 20534 LE DEPANNEUR UST La Broquerie Eastern 63370 LE DEPANNEUR AST La Broquerie Eastern 20539 ESSO - THE PAS UST The Pas Northwest 20540 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN UST Virden Western 20542 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN AST Virden Western 20545 RAMERS CARWASH AND GAS UST Beausejour Eastern 20547 CLEARVIEW CO-OP - LA BROQUERIE GAS BAR UST La Broquerie Red River 20551 FEHRWAY FEEDS AST Ridgeville Red River 20554 DOAK'S PETROLEUM - The Pas AST Gillam Northeast 20556 NINETTE GAS SERVICE UST Ninette Western 20561 RW CONSUMER PRODUCTS AST Winnipeg Red River 20562 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 29143 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 42388 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 42390 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 20563 MISERICORDIA HEALTH CENTRE AST Winnipeg Red River 20564 SUN VALLEY CO-OP - 179 CARON ST UST St. Jean Baptiste Red River 20566 BOUNDARY CONSUMERS CO-OP - DELORAINE AST Deloraine Western 20570 LUNDAR CHICKEN CHEF & ESSO UST Lundar Interlake 20571 HIGHWAY 17 SERVICE UST Armstrong Interlake 20573 HILL-TOP GROCETERIA & GAS UST Elphinstone Western 20584 VIKING LODGE AST Cranberry Portage Northwest 20589 CITY OF BRANDON AST Brandon Western 1 Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality -

Selecting Selinger: the 2009 Leadership Race and the Future of NDP Conventions in Manitoba∗

Selecting Selinger: The 2009 Leadership Race and the Future of NDP Conventions in Manitoba∗ Jared J. Wesley, University of Manitoba [email protected] Paper for Presentation at The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association Concordia University, Montreal June 2010 Abstract In a delegated convention held in October, 2009, the Manitoba New Democratic Party (NDP) selected former Finance Minister Greg Selinger to replace Canada's longest-serving and most popular premier, Gary Doer. Official appeals filed by the victor’s chief rival, Steve Ashton, and persistent criticism of the process in the media raised significant concerns over the method by which the new premier was selected. These complaints proved a fleeting fixation of the media, and have not harmed the NDP’s popularity or affected the smooth transition of the premiership from Doer to Selinger. Yet, questions persist as to whether the 2009 leadership race marked the last delegated convention in the history of the Manitoba New Democratic Party. This paper examines the 2009 leadership race in the context of contests past, analyzing the list of criticisms directed at the process. Grounding its findings in the comments of delegates to the 2009 Convention, it concludes with a series of probable choices for the party, as it begins the process of considering reforms to its leadership selection process. Leading contenders for adoption include a pure one-member, one-vote system and a modified version similar to that of the federal NDP. ∗ Funding for the 2009 Manitoba NDP Convention Study was provided by the Faculty of Arts, Duff Roblin Professorship, and Department of Political Studies at the University of Manitoba, and the Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Politics and Governance. -

Physician Directory

Physician Directory, Currently Practicing in the Province Information is accurate as of: 9/24/2021 8:00:12 AM Page 1 of 97 Name Office Address City Prov Postal Code CCFP Specialty Abara, Chukwuma Solomon Thompson Clinic, 50 Selkirk Avenue Thompson MB R8N 0M7 CCFP Abazid, Nizar Rizk Health Sciences Centre, Section of Neonatology, 665 William Avenue Winnipeg MB R3E 0L8 Abbott, Burton Bjorn Seven Oaks General Hospital, 2300 McPhillips Street Winnipeg MB R2V 3M3 CCFP Abbu, Ganesan Palani C.W. Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 CCFP Abbu, Kavithan Ganesan C.W. Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 CCFP Abdallateef, Yossra Virden Health Centre, 480 King Street, Box 400 Virden MB R0M 2C0 Abdelgadir, Ibrahim Mohamed Ali Manitoba Clinic, 790 Sherbrook Street Winnipeg MB R3A 1M3 Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology Abdelmalek, Abeer Kamal Ghobrial The Pas Clinic, Box 240 The Pas MB R9A 1K4 Abdulrahman, Suleiman Yinka St. Boniface Hospital, Room M5038, 409 Tache Avenue Winnipeg MB R2H 2A6 Psychiatry Abdulrehman, Abdulhamid Suleman 200 Ste. Anne's Road Winnipeg MB R2M 3A1 Abej, Esmail Ahmad Abdullah Winnipeg Clinic, 425 St. Mary Ave Winnipeg MB R3C 0N2 CCFP Gastroenterology, Internal Medicine Abell, Margaret Elaine 134 First Street, Box 70 Wawanesa MB R0K 2G0 Abell, William Robert Rosser Avenue Medical Clinic, 841 Rosser Avenue Brandon MB R7A 0L1 Abidullah, Mohammad Westman Regional Laboratory, Rm 146 L, 150 McTavish Avenue Brandon MB R7A 7H8 Anatomical Pathology Abisheva, Gulniyaz Nurlanbekovna Pine Falls Health Complex, 37 Maple Street, Box 1500 Pine Falls MB R0E 1M0 CCFP Abo Alhayjaa, Sahar C W Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 Obstetrics & Gynecology Abou-Khamis, Rami Ahmad Northern Regional Health, 867 Thompson Drive South Thompson MB R8N 1Z4 Internal Medicine Aboulhoda, Alaa Samir The Pas Clinic, Box 240 The Pas MB R9A 1K4 General Surgery Abrams, Elissa Michele Meadowwood Medical Centre, 1555 St. -

Citizenship Study Materials for Newcomers to Manitoba: Based on the 2011 Discover Canada Study Guide

Citizenship Study Materials for Newcomers to Manitoba: Based on the 2011 Discover Canada Study Guide Table of Contents ____________________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I TIPS FOR THE VOLUNTEER FACILITATOR II READINGS: 1. THE OATH OF CITIZENSHIP .........................................................................................1 2. WHO WE ARE ...............................................................................................................7 3. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 1) ...................................................................................13 4. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 2) ...................................................................................20 5. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 3) ...................................................................................26 6. MODERN CANADA ....................................................................................................32 7. HOW CANADIANS GOVERN THEMSELVES (PART 1) .............................................. 40 8. HOW CANADIANS GOVERN THEMSELVES (PART 2) .............................................. 45 9. ELECTIONS (PART 1) ................................................................................................. 50 10. ELECTIONS (PART 2) ...............................................................................................55 11. OTHER LEVELS OF GOVERNMENT IN CANADA ................................................... 60 12. HOW MUCH DO YOU KNOW ABOUT YOUR GOVERNMENT? .............................. -

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba Standing Committee on Public Utilities and Natural Resources

First Session- Thirty-Seventh Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba Standing Committee on Public Utilities and Natural Resources Chairperson Ms. Linda Asper Constituency of Riel Vol. L No. 5 - 10 a.m., Friday, July 14, 2000 ISSN 0713-9454 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thirty-Seventh Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation AGLUGUB, Cris The Maples N.D.P. ALLAN, Nancy St. Vital N.D.P. ASHTON, Steve, Hon. Thompson N.D.P. ASPER,Linda Riel N.D.P. BARREIT,Becky, Hon. Inkster N.D.P. CALDWELL, Drew, Hon. Brandon East N.D.P. CERILLI,Marianne Radisson N.D.P. CHOMIAK,Dave, Hon. Kildonan N.D.P. CUMMINGS, Glen Ste. Rose P.C. DACQUAY, Louise Seine River P.C. DERKACH, Leonard Russell P.C. DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk N.D.P. DOER, Gary,Hon. Concordia N.D.P. DRIEDGER, Myrna Charleswood P.C. DYCK,Peter Pembina P.C. ENNS, Harry Lakeside P.C. FAURSCHOU,David Portage Ia Prairie P.C. FILMON, Gary Tuxedo P.C. FRIESEN, Jean, Hon. Wolseley N.D.P. GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Lib. GILLESHAMMER, Harold Minnedosa P.C. HELWER, Edward Gimli P.C. HICKES,George Point Douglas N.D.P. JENNISSEN, Gerard Flin Flon N.D.P. KORZENIOWSKI,Bonnie St. James N.D.P. LATHLIN,Oscar, Hon. The Pas N.D.P. LAURENDEAU, Marcel St. Norbert P.C. LEMIEUX, Ron, Hon. La Verendrye N.D.P. LOEWEN,John Fort Whyte P.C. MACKINTOSH, Gord, Hon. St. Johns N.D.P. MAGUIRE, Larry Arthur-Virden P.C. MALOWAY,Jim Elmwood N.D.P. MARTINDALE, Doug Burrows N.D.P. -

Standing Committee on Justice

Third Session – Forty-Second Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba Standing Committee on Justice Chairperson Mr. Andrew Micklefield Constituency of Rossmere Vol. LXXV No. 1 - 5:30 p.m., Monday, November 30, 2020 ISSN 1708-6671 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Forty-Second Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation ADAMS, Danielle Thompson NDP ALTOMARE, Nello Transcona NDP ASAGWARA, Uzoma Union Station NDP BRAR, Diljeet Burrows NDP BUSHIE, Ian Keewatinook NDP CLARKE, Eileen, Hon. Agassiz PC COX, Cathy, Hon. Kildonan-River East PC CULLEN, Cliff, Hon. Spruce Woods PC DRIEDGER, Myrna, Hon. Roblin PC EICHLER, Ralph, Hon. Lakeside PC EWASKO, Wayne Lac du Bonnet PC FIELDING, Scott, Hon. Kirkfield Park PC FONTAINE, Nahanni St. Johns NDP FRIESEN, Cameron, Hon. Morden-Winkler PC GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Lib. GOERTZEN, Kelvin, Hon. Steinbach PC GORDON, Audrey Southdale PC GUENTER, Josh Borderland PC GUILLEMARD, Sarah, Hon. Fort Richmond PC HELWER, Reg, Hon. Brandon West PC ISLEIFSON, Len Brandon East PC JOHNSON, Derek Interlake-Gimli PC JOHNSTON, Scott Assiniboia PC KINEW, Wab Fort Rouge NDP LAGASSÉ, Bob Dawson Trail PC LAGIMODIERE, Alan Selkirk PC LAMONT, Dougald St. Boniface Lib. LAMOUREUX, Cindy Tyndall Park Lib. LATHLIN, Amanda The Pas-Kameesak NDP LINDSEY, Tom Flin Flon NDP MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood NDP MARCELINO, Malaya Notre Dame NDP MARTIN, Shannon McPhillips PC MICHALESKI, Brad Dauphin PC MICKLEFIELD, Andrew Rossmere PC MORLEY-LECOMTE, Janice Seine River PC MOSES, Jamie St. Vital NDP NAYLOR, Lisa Wolseley NDP NESBITT, Greg Riding Mountain PC PALLISTER, Brian, Hon. Fort Whyte PC PEDERSEN, Blaine, Hon. Midland PC PIWNIUK, Doyle Turtle Mountain PC REYES, Jon Waverley PC SALA, Adrien St. -

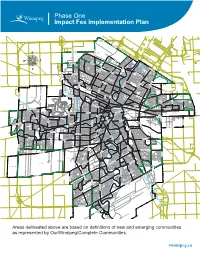

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

Consolidation Update: July 22, 2021

This document is an office consolidation of by-law amendments which has been prepared for the convenience of the user. The City of Winnipeg expressly disclaims any responsibility for errors or omissions. CONSOLIDATION UPDATE: JULY 22, 2021 THE CITY OF WINNIPEG WINNIPEG ZONING BY-LAW NO. 200/2006 A By-law of THE CITY OF WINNIPEG to promote the orderly use and development of land and the location of buildings and structures in the City of Winnipeg as defined in The City of Winnipeg Charter excepting lands covered by the Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. The CITY OF WINNIPEG, in Council assembled, enacts as follows: PART 1: ADMINISTRATION GENERAL Title 1. This By-law may be cited as the “City of Winnipeg Zoning By-law” or the “Winnipeg Zoning By-law”. Purpose 2. This By-law is intended to promote orderly and thoughtful development of real property and development in the city, except for the part of the city governed by the Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law, in order to promote the health, safety and general welfare of the City and to implement the provisions of OurWinnipeg and the adopted Secondary Plans included in Schedule A. amended 95/2014 Application 3. (1) This By-law controls and regulates the use and development of land in the City of Winnipeg, with the exception of the area of the city governed by the Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law, as shown on the Zoning Maps in Schedule B to this By-law. (2) All activity and development within the area to which this By-law applies must conform to the provisions of this By-law and must be consistent with OurWinnipeg and with any adopted Secondary Plans that cover the land in question. -

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS

Third Session- Thirty-Seventh Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Official Report (Hansard) Published under the authority of The Honourable George Hickes Speaker Vol. LII No. 14 - 1:30 p.m., Tuesday, December 4, 2001 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thirty-Seventh Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation AGLUGUB, Cris The Maples N.D.P. ALLAN, Nancy St. Vital N.D.P. ASHTON,Steve, Hon. Thompson N.D.P. ASPER, Linda Riel N.D.P. BARRETT,Becky, Hon. Inkster N.D.P. CALDWELL, Drew, Hon. Brandon East N.D.P. CERILLI, Marianne Radisson N.D.P. CHOMIAK, Dave, Hon. Kildonan N.D.P. CUMMINGS, Glen Ste. Rose P.C. DACQUA Y,Louise Seine River P.C. DERKACH,Leonard Russell P.C. DEWAR, Gregory Selkirk N.D.P. DOER, Gary,Hon. Concordia N.D.P. DRIEDGER. Myrna Charleswood P.C. DYCK,Peter Pembina P.C. ENNS, Harry Lakeside P.C. FAURSCHOU,David Portage Ia Prairie P.C. FRIESEN, Jean,Hon. Wolseley N.D.P. GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Lib. GILLESHAMMER, Harold Minnedosa P.C. HELWER, Edward Gimli P.C. HICKES,George Point Douglas N.D.P. JENNISSEN, Gerard Flin Flon N.D.P. KORZENIOWSKI, Bonnie St. James N.D.P. LATHLIN,Oscar, Hon. The Pas N.D.P. LAURENDEAU, Marcel St. Norben P.C. LEMIEUX, Ron,Hon. La Verendrye N.D.P. LOEWEN, John FonWhyte P.C. MACKINTOSH, Gord,Hon. St. Johns N.D.P. MAGUIRE,Larry Anhur-Virden P.C. MALOWA Y,Jim Elmwood N.D.P. MARTINDALE, Doug Burrows N.D.P. McGIFFORD, Diane,Hon. Lord Roberts N.D.P. -

INDEX of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba

INDEX of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS 36-37 Elizabeth II Second Session - Thirty-Third Legislature which opened the 26th of February, 1987 and prorogued by proclamation the 10th of February, 1988 Volume XXXV Published under the authority ol the Honourable M. Phillips, Speaker. Printed by the Office of the Queens Printer, Pro11ince of Manitoba TABLE OF CONTENTS Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Second Session - Thirty-Third Legislature Table of Contents .................................. ............................................................ List of Members ................................................................................................. II Members of Executive Council.......................................................................... Ill-VI Legislative Assembly.......................................................................................... VII Standing and Special Committees.................................................................... VIII Bills - Alphabetical Listing................................................................................. VIII BiHs - Numerical Listing ..................................................................................... XII Sittings, dates and pages............ ...................................................................... XV Index by Subject ................... ............................................................................. 1 Index by Member ............................................................................. -

“Just Doing What Needs to Be Done:” Rural Women's Everyday

“Just doing what needs to be done:” Rural Women’s Everyday Peacebuilding on the Prairies by Jessica Robin Neustaeter A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Peace and Conflict Studies University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2016 Jessica Robin Neustaeter ABSTRACT Usually bubbling under the surface of the ordinary everyday routines of life, women’s volunteering in their communities, helping out and just doing what needs to be done, represent a significant phenomenon in sustaining and developing human life and civilization. Embedded within their everyday community action is a dialectical learning and cognitive praxis which informs their situated public care practice. Grassroots peacebuilding is dependent on the efforts of volunteers. As well, volunteering itself is a means for building social cohesion, solidarity and trust—factors fundamental to sustainable development and peace. Rural women’s community involvement is situated within the everyday of their diverse communities. There is diversity both within and between rural communities; as well rural women represent a diverse group in regards to age, race, class, ethnicity, language, marital and family status, ability, and religion. Blending participant observation and in-depth interviewing, this ethnographic study explored rural women’s community involvement practice and learning in South-Central Manitoba. This study invited women from across the region; representing a mix of age, race, education, ability, ethnicity, religion and areas of involvement, to share their stories of being involved in their communities. Their narratives revealed a rich story of women’s peacebuilding for individual and community wellbeing fitting into a tradition of rural women’s community development.