Book Lists and Their Meaning Malcolm Walsby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N E W S L E T T E R Section's Homepage

August 2011 Section on Rare Books and Manuscripts N e w s l e t t e r Section's Homepage: http://www.ifla.org/en/rare-books-and-manuscripts Contents People 2 From the Editors 3 2011 Midterm meeting in Madrid 4 From the Libraries 5 Exhibitions 12 Events and conferences 21 Projects 28 Publications 38 Web news 42 Cooperation 44 People Chair: Raphaële Mouren Université de Lyon / ENSSIB 17-21, Boulevard du 11 Novembre 1918 69623 VILLEURBANNE, France Tel. +(33)(0)472444343 Fax +(33)(0)472444344 E-mail: [email protected] Secretary and Treasurer: Anne Eidsfeldt The National Library of Norway Post Box 2674 Solli OSLO, NO-0203 Norway Tel. +(47)(23)276095 Fax +(47)(75)121222 E-mail: [email protected] Information Coordinator: Isabel García-Monge Special Collections, Spanish Bibliographical Heritage Union Catalogue, Ministry of Culture C/ Alfonso XII, 3-5, ed. B 28014 MADRID, Spain Tel. +(34) 91 5898805 Fax +(34) 91 5898815 E-mail: [email protected] Editor of the Newsletter: C.C.A.E. (Chantal) Keijsper Division of Special Collections, University Library, Leiden University Witte Singel 27 2311 BG LEIDEN, The Netherlands Tel. +(31)(71)5272832 Fax +(31)(71)5272836 E-mail: [email protected] 2 From the Editors The present edition has been prepared by Chantal Keijsper and Ernst-Jan Munnik (Leiden University Library). The newsletter will only be published in electronic format in future. This gives us the opportunity to include illustrations in the text and thus to enhance the visual attractiveness of the newsletter. -

![A Virtual National Library for Germany – the SAMMLUNG DEUTSCHER DRUCKE [Collection of German Printed Works]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4967/a-virtual-national-library-for-germany-the-sammlung-deutscher-drucke-collection-of-german-printed-works-624967.webp)

A Virtual National Library for Germany – the SAMMLUNG DEUTSCHER DRUCKE [Collection of German Printed Works]

World Library and Information Congress: 69th IFLA General Conference and Council 1-9 August 2003, Berlin Code Number: 140-E Meeting: 173. National Libraries - Workshop Simultaneous Interpretation: - A virtual National Library for Germany – the SAMMLUNG DEUTSCHER DRUCKE [Collection of German Printed Works] GERD-J. BÖTTE Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, Germany The federal structure of Germany favoured the development of a great variety of well-stocked libraries. None however had the means of acquiring in their entirety the printed works published in the German- speaking countries. Only as late as 1913, after the foundation of the Deutsche Buecherei, was the collection of the modern German book production achieved. The gaps of the past are considerable and unfavourable to scholarly research. In order to make up for this deficit, the SAMMLUNG DEUTSCHER DRUCKE was founded in 1989. Since then five libraries have been collecting works printed between 1450 and 1912. When they were joined by Die Deutsche Bibliothek in 1995, a virtual national library was established. The problem "A single German national library remains a fiction." – at least according to Michael P. Olson, who in 1996 chose this apodictic phrase as the very beginning of his study about The Odyssey of a German National Library1. What is so bewildering about Olson’s statement? The fact that it is true? A national library, in Olson’s understanding, is presumed to have four functions: 1) “to be the nation’s bibliographic centre, 2) to be the repository for the nation’s printed works, 3) to collect foreign literature as comprehensively as funds allow, 4) to have outstanding retrospective collections.”2 Of course, we do have Die Deutsche Bibliothek as Germany’s national bibliographic centre and repository for its modern book production. -

Rare Book List I

RARE BOOK LIST I Rare Book List I ERASMUSHAUS HAUS DER BÜCHER AG • BÄUMLEINGASSE 18 • 4001 BASEL • +41 61 228 99 44 • [email protected] • WWW.ERASMUSHAUS.CH 1 AMMAN, Jost (1539-1591) & Philipp LONITZER (+1599). Insignia sacrae caesareae maiestatis, principum electorum, ac aliquot illustrissimarum, illustrium, nobilium, & aliarum familiarum, formis artificiosissimis expressa: Addito cuiq; peculiari symbolo, & carmine octastico, quibus cum ipsum Insigne, tum symbolum, ingeniosè, ac sine ulla arrogantia vel mordacitate, liberaliter explicantur ... 4° (198x147 mm). [118 of 120] ll. lacking ll. [82 and 83]. 19th century half Russia leather gilt. Top and bottom of spine slightly scuffed. Frankfurt am Main, (Georg Corvinus for Siegmund Feyerabend, August), 1579. CHF 2500 Jost Amman’s famous book of coat-of-arms in its rare first edition, published before its German translation (Stam- und Wapenbuch). The illustrations are generally family arms on the versos, and allegories, mythological figures, social types, etc., on the rectos. The allegorical interpretations of both are by the historian Philipp Lonitzer (-1599), a brother of the physician and botanist Adam Lonitzer. The last 14 p. before the colophon have blank shields, four to a page. The preceding 40 p. mostly have full-page blank shields with figures, alternating with allegorical figures, both without text. The woodcuts are by Jost Amman (some signed IA) and other artists represented by the initials MF, LF, MB, MT(?), CS. Provenance: Damiano Muoni (1820-1894), Italian historian and bookdealer (stamp on ll. 2, 4, 26, 50 and last leaf). – Leon S. Olschki (1861-1940), famous Italian antiquarian bookdealer and publisher. References: Becker 24; VD 16 (Online Kat.) L-2468; Lipperheide 638; Hiler/Hiler 25; Stirling Maxwell Emblem Catalogue SM-647; Adams L 1458. -

Catalogue 2011

Antiquariat Aix-la-Chapelle 1 Greek Tragedies in Best Edition First complete edition. AESCHYLUS (graece). Tragoediae VII. Que cùm omnes multo quàm antea castigatiores eduntur, tum verò una, quae mutila & decurata prius erat, integra nunc profertur. Petri Victorii cura et diligentia. [Geneva]: Henricus Stephanus 1557. 4 unnumbered leaves, 395 pages, 1 p., with woodcut printer’s device on title , 18 th century mottled calf with richly gilt spine, 4° (24,5 x 17 cm). First complete edition. Adams A 266; Dibdin I, 237: ’An excellent and beautiful copy. The Agamemnon is published in it, for the first time, complete. This edition is rare and dear’. Edited by Petrus Victorius (Piero Vettori 1499 - 1585), one of the greatest classical scholars of 16th century Italy ‘certainly the foremost representative’ (Sandys II, 135) and Henri Estienne. Very attractive copy. Early Arabic Astronomy ALBOHAZEN HALY filii Abenragel. De iudiciis Astrorum Libri octo. Conversi … per Antonium Stupam … Accessit huic operi … Compendium duodecim domorum coelestium Authore PETRO LIECHTENSTEIN. Basle: Henricus Petri March 1571. 14 unnumbered leaves (last blank), 586 pages, 1 unn. leaf, with woodcut printer’s device on title and last leaf, some woodcut diagrams and horoscopes, and numerous woodcut initials, 17 th century full calf, spine gilt, folio (33 x 21 cm). First Edition with the contribution by Petrus Liechtenstein . (first Venice: Ratdolt 1485). Adams A 70; VD 16 A 1884; VD 16 L 1665 (for the article by Liechtenstein); Houzeau & Lancaster 3870; Zinner 2544. Scarce first edition of this translation. One of the most popular astrological compendiums in East and West, even Kepler is said to have used information from this text. -

Midwinter Minutes

Minutes Bibliographic Standards Committee ALA Midwinter Meeting 2010 Saturday, 16 January, 2010, 8:00 a.m.-12:00 p.m. (0800-1200) Hyatt Regency Boston – Martha’s Vineyard Room Boston, Massachusetts 1. Introduction of members and visitors 2. Settlement of the agenda 3. Approval of Annual 2009 minutes 4. Controlled Vocabularies Subcommittee 5. Examples to accompany DCRM(B) 6. Revision of Standard Citation Forms for Rare Book Cataloging 7. Reports (to be appended to the minutes): Web Resources for the Rare Materials Cataloger; CC:DA Report 8. Bibliographic Standard Record for Rare Printed Books 9. Preconference seminars 10. Preconference workshops 11. DCRM(M): Descriptive Cataloging of Rare Materials (Music) 12. DCRM(C): Descriptive Cataloging of Rare Materials (Cartographic) 13. DCRM(MSS): Descriptive Cataloging of Rare Materials (Manuscripts) 14. DCRM(G): Descriptive Cataloging of Rare Materials (Graphics) 15. Assignments 16. New business 17. Announcements from the floor 18. Adjournment Appendix A. Web Resources for the Rare Materials Cataloger Appendix B. CC:DA Report 1. Introduction of members and visitors Members present: Marcia Barrett, University of Alabama; Erin Blake, Folger Shakespeare Library; Ann Copeland, Pennsylvania State University; Martha Lawler, Louisiana State University in Shreveport; Kate Moriarty, Saint Louis University; Ann Myers, Southern Illinois University Carbondale (secretary); Jennifer Nelson, Robbins Collection, Law Library, University of California, Berkeley; Margaret Nichols, Cornell University; Nina Schneider, Clark Library, University of California, Los Angeles (controlled vocabularies editor); Stephen Skuce, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (chair); Bruce Tabb, University of Oregon; Eduardo Tenenbaum, Princeton University; Seanna Tsung, Library of Congress. Liaisons: Larry Creider, New Mexico State University (ACRL to CC:DA liaison); Fernando Peña, Grolier Club (RBMS Exec liaison); Elizabeth Robinson, Library of Congress (LC liaison). -

The Glass Case Antiquarian Books from the 15 Century to 1900 Many

The Glass Case Antiquarian Books from the 15 th century to 1900 Many About Women On-Line Only: Catalogue # 208 Second Life Books Inc. ABAA- ILAB P.O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA 01237 413-447-8010 fax: 413-499-1540 Email: [email protected] The Glass Case: Antiquarian ON-LINE ONLY : CATALOGUE # 208 Terms : All books are fully guaranteed and returnable within 7 days of receipt. Massachusetts residents please add 5% sales tax. Postage is additional. Libraries will be billed to their requirements. Deferred billing available upon request. We accept MasterCard, Visa and American Express. ALL ITEMS ARE IN VERY GOOD OR BETTER CONDITION , EXCEPT AS NOTED . Orders may be made by mail, email, phone or fax to: Second Life Books, Inc. P. O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA. 01237 Phone (413) 447-8010 Fax (413) 499-1540 Email:[email protected] Search all our books at our web site: www.secondlifebooks.com or www.ABAA.org . DISPUTING THE "DISPUTATIO" - TWO CONTEMPORARY REFUTATIONS Treatise on the Question Do Women Have Souls 1. (ACIDALIYS, Valens,?). ADMONITIO THEOLOGICA ; facultatis in Academia Witebergensi, ad scholasticam Iuventutem, de Libello famoso & blasphemo recens sparso, suius titulus ets: Disputatio nova contra Mulieres, qua ostenditur, eas homines non esse. Wittenberg: Widow of Mattheus Welack, 1595. First Edition. 4to, (6) leaves, with typographical ornament on the title-page and at the end.VD 16 W- 3700; Universal STC no. 609252. BOUND WITH: [GEDIK, Simon?] RUFUTATIO OPPOSITA … autoris thesibus, quibus humanam naturam foeminei sexus impugnat, in qua praecipuae calumniate huius mendacis spiritus refutantur, quae sit illius ntention ostenditur, et studiosi pietatis omnesq(ue) Christiani monentur, ut sibi caveant a tam Diabolico scripto. -

Piloting a National Programme for the Digitization of Medieval Manuscripts in Germany

Vol. 24, no. 1 (2014) 2–16 | ISSN: 1435-5205 | e-ISSN: 2213-056X Piloting a National Programme for the Digitization of Medieval Manuscripts in Germany Claudia Fabian Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich [email protected] Carolin Schreiber Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich [email protected] Abstract An initiative to develop a concerted national programme for the digitiza- tion of medieval manuscripts in Germany was launched by five German manuscript centres in January 2013. This new proposal aims at the devel- opment of a master plan for the digitization of nearly all surviving medi- eval manuscripts in Germany and at the establishment of a new funding programme of the DFG (German Research Foundation), the largest research funding organization in Germany. Besides this fundamental financial aspect, other objectives are the diffusion of technical standards and know-how to less experienced cultural heritage institutions and the creation of a nationwide network of competent part- ners, e.g. in the areas of digitization itself, long-term storage of digital data, the administration of persistent identifiers, and the internet presentation of digital collections. An important role will be played by the German manu- scripts portal, Manuscripta Mediaevalia, which is intended as the central hub for both the presentation of digital collections of German manuscripts, but also of the relevant metadata, that is, digital and ideally searchable full- text versions of scholarly, in-depth manuscript descriptions. Of course, this This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license Igitur publishing | http://liber.library.uu.nl/ | URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-116281 2 Liber Quarterly Volume 23 Issue 4 2014 Claudia Fabian and Carolin Schreiber centralization and aggregation will also facilitate the exchange of data with other institutions. -

Catalog # 215 (2 Nd Edition, Enlarged)

WOMEN On-Line Only: Catalog # 215 (2 nd edition, enlarged) Second Life Books Inc. ABAA- ILAB P.O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA 01237 413-447-8010 fax: 413-499-1540 Email: [email protected] women On-Line Only Catalog # 215 nd (2 edition, enlarged ) Terms : All books are fully guaranteed and returnable within 7 days of receipt. Massachusetts residents please add 5% sales tax. Postage is additional. Libraries will be billed to their requirements. Deferred billing available upon request. We accept MasterCard, Visa and American Express. ALL ITEMS ARE IN VERY GOOD OR BETTER CONDITION , EXCEPT AS NOTED . Orders may be made by mail, email, phone or fax to: Second Life Books, Inc. P. O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA. 01237 Phone (413) 447-8010 Fax (413) 499-1540 Email:[email protected] Search all our books at our web site: www.secondlifebooks.com or www.ABAA.org . MULIERES HOMINES NON ESSE - ARE WOMEN HUMAN? 1. [ACIDALIYS, Valens,?] GEDDICCVS, (Gedik) Simon . DEFENSIO SEXUS MULIEBRIS, Opposita futilissimae disputationi recenss editae, qua suppresso authoris & authoris & typographi nomine blaspheme contenditur, Mulieres homines non esse. Leipzig: Michael Lantzenberger (for Henning Grosse), 1595. First Edition. 4to, (31) leaves (lacks last blank), title-page neatly mounted on a stub, with printer's mark on the title-page. BOUND WITH/ [ACIDALIYS, Valens,?] DISPUTATIO NOVA CONTRA MULIERES qua probatur eas Homines non esse. [ np, np, 1195 (but ca 1660). 4to, (12) leaves. The two works bound together in quarter blue morocco (a bit faded and rubbed, upper part of spine gone), marble boards, red morocco label with gilt lettering on the spine, some light browning, but a fine copy (the second tract is a little smaller than the first). -

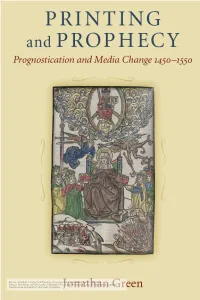

Printing and Prophecy: Prognostication and Media Change 1450-1550

Green, Jonathan. Printing and Prophecy: Prognostication and Media Change 1450-1550. E-book, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.3209249. Downloaded on behalf of Unknown Institution Printing and Prophecy Green, Jonathan. Printing and Prophecy: Prognostication and Media Change 1450-1550. E-book, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.3209249. Downloaded on behalf of Unknown Institution Green, Jonathan. Printing and Prophecy: Prognostication and Media Change 1450-1550. E-book, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.3209249. Downloaded on behalf of Unknown Institution <= PRINTING AND PROPHECY Prognostication and Media Change 1450–1550 <= Jonathan Green The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor Green, Jonathan. Printing and Prophecy: Prognostication and Media Change 1450-1550. E-book, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.3209249. Downloaded on behalf of Unknown Institution Copyright © Jonathan Green 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Green, Jonathan. -

Rare Book Miscellany

Rare Book Miscellany On-Line Only: Catalog # 221 Second Life Books Inc. ABAA- ILAB P.O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA 01237 413-447-8010 fax: 413-499-1540 Email: [email protected] Rare Book Miscellany On-Line Only Catalog # 221 Terms : All books are fully guaranteed and returnable within 7 days of receipt. Massachusetts residents please add 5% sales tax. Postage is additional. Libraries will be billed to their requirements. Deferred billing available upon request. We accept MasterCard, Visa and American Express. ALL ITEMS ARE IN VERY GOOD OR BETTER CONDITION , EXCEPT AS NOTED . Orders may be made by mail, email, phone or fax to: Second Life Books, Inc. P. O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA. 01237 Phone (413) 447-8010 Fax (413) 499-1540 Email:[email protected] Search all our books at our web site: www.secondlifebooks.com Item # 3 1. ABBEY, Edward. DESERT SOLITAIRE, A season in the wilderness. NY: McGraw-Hill, (1968). First Edition. 8vo, pp. 269. Drawings by Peter Parnall. A nice copy in little nicked dj. Scarce. [38528] $1,000.00 A moving tribute to the desert, the personal vision of a desert rat. The author's fourth book and his first work of nonfiction. This collection of meditations by then park ranger Abbey in what was Arches National Monument of the 1950s was quietly published in a first edition of 5,000 copies 2. ABEL, Mrs. Mary Hinman. PRACTICAL SANITARY AND ECONOMIC COOKING adapted to persons of moderate and small means. The Lomb Prize Essay. [Rochester, NY]: American Public Health Assoc., 1890. -

VD 16: Sigel Der Zitierten Bibliographien

Sigel der zitierten Bibliographien Adams Cat. Adams, Herbert Mayow: Catalogue of books printed on the continent of Europe, 1501-1600 in Cambridge libraries. 2 Bde. Cambridge 1967. Alb. Reuch. Alberts, Hildegard: Reuchlins Drucker Thomas Anshelm mit besonderer Berücksichtigung seiner Pforzheimer Presse. In: Johannes Reuchlin 1455-1522. Festgabe seiner Vaterstadt Pforzheim zur 500. Wiederkehr seines Geburtstages. Hrsg. v. Manfred Krebs. Pforzheim 1955, S. 205-265. Alt Bild. Alt, Robert: Bilderatlas zur Schul- und Erziehungsgeschichte. Bd. 1: Von der Urgesellschaft bis zum Vorabend der bürgerlichen Revolutionen. Berlin 1960. And. Not. Anderson, Peter John: Notes on academic theses with bibliography of Duncan Liddel. Aberdeen 1912. (Aberdeen university studies. 58.) Arnsw. Kat. (Arnswaldt, Werner Konstantin von): Katalog der fürstlich Stolberg-Stolberg'schen Leichenpredigtensammlung. Bd. 1- 4,2. Leipzig 1927-1935. Baader Baader, Peter: Das Druck- und Verlagshaus Albin-Strohecker zu Mainz 1598-1631. In: Archiv für Geschichte des Buchwesens l (1959), S. 513-569. Badalić Badalić, Josip: Jugoslavica usque ad annum MDC. Bibliographie der südslawischen Frühdrucke. Baden-Baden 1959. (Bibliotheca bibliographica Aureliana. 2.) Baecht.Man. Baechtold, Jakob: Nikolaus Manuel. Frauenfeld 1878. (Bibliothek älterer Schriftwerke der deutschen Schweiz und ihrer Grenzgebiete, [Ser. 1] 2.) Bah. Lal. Bahder, Karl von: Das Lalebuch (1597) mit den Abweichungen und Erweiterungen der Schiltbürger (1598) und des Grillenvertreibers (1603). Halle a. S. 1914. (Neudrucke deutscher Literaturwerke des XVI. und XVII. Jahrhunderts. 236-239.) Bahlm. Nachtr. Bahlmann, P.: Ein Nachtrag zu Hennen, Trierer Heiligtumsbücher. In: Zentralblatt für Bibliothekswesen 6 (1889), S. 458-461. Bail. Colm. Baillet, Lina: Colmar (Haut-Rhin). In: Répertoire bibliographique des livres imprimés en France au seizième siècle. -

HANS SACHS, Disputation Zwischen Einem Chorherren Und

HANS SACHS, Disputation zwischen einem Chorherren und Schuchmacher darinn das wort gottes unnd ein recht Christlich wesen verfochten würdt In German, imprint on paper with nearly full-page woodcut Germany (Bamberg), Georg Erlinger, 1524 4o, iii (modern paper ) + 12 + iii (modern paper) folios, complete (collation, a4 b4 c4 [$3, -Ai, first leaves signed with a letter only, last folio is an integral blank], catchwords at the end of quires a and b, thirty-four long lines in gothic type, names of speakers set out in larger type, four-line typeset decorative initial, title page with large, nearly full-page woodcut depicting full-length figures of the Shoemaker, Canon, and a female Cook, with traces of old wash color, in near perfect condition apart from very minor soiling and discoloration. Bound in modern blind-tooled brown calf over pasteboard in excellent condition. Dimensions 182 x 146 mm. In near perfect condition, this is a rare copy of the first edition (first issue) of one of the most important Reformation dialogues, the Dispute between the Canon and the Shoemaker by Hans Sachs. The amusing (and instructive) content of this work is amplified by its eye-catching title-page, showing the shoemaker, the canon, and the canon’s cook, appealing to Sachs’ target audience, common people without knowledge of Latin who were eager to embrace the new message of the Reformation. PROVENANCE 1. Printed by Georg Erlinger (c. 1485-1541) in Bamberg in 1524; Erlinger was born in Augsburg, where he worked as a Formschneider (wood-block cutter). He was active as a printer in Bamberg from 1522, and printed numerous works by Luther and his followers.