White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project TS&L Type, Size, and Location TSP Transportation System Plan TSS Total Suspended Solids U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2019 Progress Report

Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2019 Progress Report December 2019 Progress Report i This page intentionally left blank. ii Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2, 2019 (Electronic Transmittal Only) The Honorable Governor Inslee The Honorable Kate Brown WA Senate Transportation Committee Oregon Transportation Commission WA House Transportation Committee OR Joint Committee on Transportation Dear Governors, Transportation Commission, and Transportation Committees: On behalf of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) and the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), we are pleased to submit the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program status report, as directed by Washington’s 2019-21 transportation budget ESHB 1160, section 306 (24)(e)(iii). The intent of this report is to share activities that have lead up to the beginning of the biennium, accomplishments of the program since funding was made available, and future steps to be completed by the program as it moves forward with the clear support of both states. With the appropriation of $35 million in ESHB 1160 to open a project office and restart work to replace the Interstate Bridge, Governor Inslee and the Washington State Legislature acknowledged the need to renew efforts for replacement of this aging infrastructure. Governor Kate Brown and the Oregon Transportation Commission (OTC) directed ODOT to coordinate with WSDOT on the establishment of a project office. The OTC also allocated $9 million as the state’s initial contribution, and Oregon Legislative leadership appointed members to a Joint Committee on the Interstate Bridge. These actions demonstrate Oregon’s agreement that replacement of the Interstate 5 Bridge is vital. As is conveyed in this report, the program office is working to set this project up for success by working with key partners to build the foundation as we move forward toward project development. -

Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory Report

Report to the Washington State Legislature Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory December 2017 Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory Errata The Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory published to WSDOT’s website on December 1, 2017 contained the following errata. The items below have been corrected in versions downloaded or printed after January 10, 2018. Section 4, page 62: Corrects the parties to the tolling agreement between the States—the Washington State Transportation Commission and the Oregon Transportation Commission. Miscellaneous sections and pages: Minor grammatical corrections. Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory | December 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary. .1 Section 1: Introduction. .29 Legislative Background to this Report Purpose and Structure of this Report Significant Characteristics of the Project Area Prior Work Summary Section 2: Long-Range Planning . .35 Introduction Bi-State Transportation Committee Portland/Vancouver I-5 Transportation and Trade Partnership Task Force The Transition from Long-Range Planning to Project Development Section 3: Context and Constraints . 41 Introduction Guiding Principles: Vision and Values Statement & Statement of Purpose and Need Built and Natural Environment Navigation and Aviation Protected Species and Resources Traffic Conditions and Travel Demand Safety of Bridge and Highway Facilities Freight Mobility Mobility for Transit, Pedestrian and Bicycle Travel Section 4: Funding and Finance. 55 Introduction Funding and Finance Plan Evolution During -

Columbia River System Operation Review Final Environmental Impact Statement

Columbia River System Operation Review Final Environmental Impact Statement AppendixL Soils, Geology and Groundwater 11""I ,11 ofus Engineers Armv Corps ".'1 North Pacific Division DOEIEIS-O I 70 November 1995 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT IN THE SOR PROCESS The Bureau of Reclamation, Corps of Engineers, and Bonneville Power Administration wish to thank those who reviewed the Columbia River System Operation Review (SOR) Draft EIS and appendices for their comments. Your comments have provided valuable public, agency. and tribal input to the SOR NEPA process, Throughout the SOR. we have made a continuing effort to keep the public informed and involved. Fourteen public scoping meetings were held in 1990. A series of public roundtables was conducted in November 1991 to provide an update on the status of SOR studies. Tbe lead agencies went back 10 most of the 14 communities in 1992 with 10 initial system operating strategies developed from the screening process. From those meetings and other consultations, seven SOS alternatives (with options) were developed and subjected to full-scale analysis. The analysis results were presented in the Draft EIS released in July 1994. The lead agencies also developed alternatives for the other proposed SOR actions, including a Columbia River Regional Forum for assisting in the detennination of future sass, Pacific Northwest Coordination Agreement alternatives for power coordination, and Canadian Entitlement Allocation Agreements alternatives. A series of nine public meetings was held in September and October 1994 to present the Draft EIS and appendices and solicit public input on the SOR. The lead agencies·received 282 fonnal written comments. Your comments have been used to revise and shape the alternatives presented in the Final EIS. -

White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project

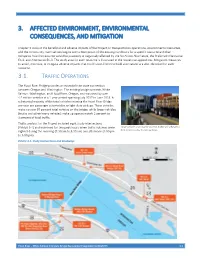

3. AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT, ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES, AND MITIGATION Chapter 3 looks at the beneficial and adverse impacts of the Project on transportation operations, environmental resources, and the community. Each section begins with a description of the existing conditions for a specific resource and then compares how the resource would be positively or negatively affected by the No Action Alternative, the Preferred Alternative EC-2, and Alternative EC-3. The study area for each resource is illustrated in the respective appendices. Mitigation measures to avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse impacts that could result from the build alternatives are also identified for each resource. 3.1. TRAFFIC OPERATIONS The Hood River Bridge provides an essential interstate connection between Oregon and Washington. The existing bridge connects White Salmon, Washington, and Hood River, Oregon, and was used by over 4.5 million vehicles in a 1-year period spanning July 2017 to June 2018. A substantial majority of the total vehicles crossing the Hood River Bridge per year are passenger automobiles or light-duty pickups. These vehicles make up over 97 percent total vehicles on the bridge, while larger vehicles (trucks and other heavy vehicles) make up approximately 2 percent to 3 percent of total traffic. Traffic analysis for the Project included eight study intersections (Exhibit 3-1) and examined for two peak hours when traffic volumes were Large vehicles crossing the existing bridge are advised to highest during the morning (7:30 am to 8:30 am) and afternoon (4:00 pm turn in mirrors due to narrow lanes. to 5:00 pm). Exhibit 3-1. -

Hood River – White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project SDEIS

(OR SHPO Case No. 19-0587; WA DAHP Project Tracking Code: 2019-05-03456) Draft Historic Resources Technical Report October 1, 2020 Prepared for: Prepared by: In coordination with: 111 SW Columbia 851 SW Sixth Avenue Suite 1500 Suite 1600 Portland, Oregon 97201 Portland, Oregon 97204 This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Project Alternatives ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. No Action Alternative .......................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Preferred Alternative EC-2 ................................................................................................... 8 2.3. Alternative EC-1 ................................................................................................................ 14 2.4. Alternative EC-3 ................................................................................................................ 19 2.5. Construction of the Build Alternatives ............................................................................... 23 3. Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

Corridor Plan

HOOD RIVER MT HOOD (OR HIGHWAY 35) Corridor Plan Oregon Department of Transportation DOR An Element of the HOOD RIVER-MT. HOOD (OR 35) CORRIDOR PLAN Oregon Department of Transportahon Prepared by: ODOT Region I David Evans and Associates,Inc. Cogan Owens Cogan October 1997 21 October, 1997 STAFF REPORT INTERIM CORRIDOR STRATEGY HOOD RIVER-MT. HOOD (OR HWY 35) CORRIDOR PLAN (INCLUDING HWY 281 AND HWY 282) Proposed Action Endorsement of the Hood River-Mt. Hood (OR HWY 35) Corridor Strategy. The Qregon Bep ent of Transportation (ODOT) has been working wi& Tribal and local governments, transportation service providers, interest groups, statewide agencies and stakeholder committees, and the general public to develop a long-term plan for the Hood River-Mt. Hood (OR HWY 35) Corridor. The Hood River-Mt. Hood Corridor Plan is a long-range (20-year) program for managing all transportation modes within the Oregon Highway 35 corridor from the 1-84 junction to the US 26 junction (see Corridor Map). The first phase of that process has resulted in the attached Interim Com'dor Stvategy. The Interim Corridor Strategy is a critical element of the Hood River- Mt. Hood Corridor Plan. The Corridor Strategy will guide development of the Corridor Plan and Refinement Plans for specific areas and issues within the corridor. Simultaneous with preparation of the Corridor Plan, Transportation System Plans (TSPs) are being prepared for the cities of Hood River and Cascade Locks and for Hood River County. ODOT is contributing staff and financial resources to these efforts, both to ensure coordination between the TSPs and the Corridor Plan and to avoid duplication of efforts, e.g. -

Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement

I N T E R S TAT E 5 C O L U M B I A R I V E R C ROSSING Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement May 2011 Title VI The Columbia River Crossing project team ensures full compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by prohibiting discrimination against any person on the basis of race, color, national origin or sex in the provision of benefits and services resulting from its federally assisted programs and activities. For questions regarding WSDOT’s Title VI Program, you may contact the Department’s Title VI Coordinator at (360) 705-7098. For questions regarding ODOT’s Title VI Program, you may contact the Department’s Civil Rights Office at (503) 986-4350. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information If you would like copies of this document in an alternative format, please call the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) project office at (360) 737-2726 or (503) 256-2726. Persons who are deaf or hard of hearing may contact the CRC project through the Telecommunications Relay Service by dialing 7-1-1. ¿Habla usted español? La informacion en esta publicación se puede traducir para usted. Para solicitar los servicios de traducción favor de llamar al (503) 731-4128. Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement This page intentionally left blank. May 2011 Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement Cover Sheet Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement: Submitted By: Derek Chisholm Mike Gallagher Rosalind Keeney Elisabeth Leaf Julie Osborne Saundra Powell Jessica Roberts Megan Taylor Parametrix May 2011 Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing Historic Built Environment Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement This page intentionally left blank. -

The World's Largest Floods, Past and Present: Their Causes and Magnitudes

fc Cover: A man rows past houses flooded by the Yangtze River in Yueyang, Hunan Province, China, July 1998. The flood, one of the worst on record, killed more than 4,000 people and drove millions from their homes. (AP/Wide World Photos) The World’s Largest Floods—Past and Present By Jim E. O’Connor and John E. Costa Circular 1254 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2004 For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: O’Connor, J.E., and Costa, J.E., 2004, The world’s largest floods, past and present—Their causes and magnitudes: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1254, 13 p. iii CONTENTS Introduction. 1 The Largest Floods of the Quaternary Period . 2 Floods from Ice-Dammed Lakes. 2 Basin-Breach Floods. 4 Floods Related to Volcanism. 5 Floods from Breached Landslide Dams. 6 Ice-Jam Floods. 7 Large Meteorological Floods . 8 Floods, Landscapes, and Hazards . 8 Selected References. 12 Figures 1. Most of the largest known floods of the Quaternary period resulted from breaching of dams formed by glaciers or landslides. -

(Interstate Tol1 Bridge) State Route 433 Spanning Langview Ca

LONGVIEW BRIDGE HAER No. WA-89 (Lewis & Clark Bridge) (Columbia River Bridge) (Interstate Tol1 Bridge) State Route 433 spanning the Columbia River Langview Cawlitz County Washington > WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA PHOTDBRAPHS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERINS RECORD NATIONAL PARK SERVICE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR P.O. BOX 37127 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20013-7127 r H*E£ HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD LONGVIEW BRIDGE (Lewis and Clark Bridge) I- * (Columbia River Bridge) (Interstate Toll Bridge) HAER No. WA-89 Location: State Route 433 spanning the Columbia River between Multnomah County, Oregon and Cowlitz County, Washington; beginning at milepost 0.00 on state route 433. UTM: 10/503650/5106420 10/502670/5104880 Quad: Rainier, Oreg.-Wash, Date of Construction: 1930 Engineer: Joseph B. Strauss, Strauss Engineering Corp., Chicago, IL Fabricator/Builder: Bethlehem Steel Company, Steelton, PA, general contractor Owner: 1927-1935: Columbia River—Longview Bridge Company. 1936-1947: Longview Bridge Company operated by Bethlehem Steel. 1947-1965: Washington Toll Bridge Authority. 1965 to present: Washington Department of Highways, since 1977, Washington State Department of Transportation, Olympia, Washington• Present Use: Vehicular and pedestrian traffic Significance: The Longview Bridge, designed by engineer Joseph B. Strauss, was at time of construction the longest cantilever span in North America with its 1,200' central section. Extreme vertical and horizontal shipping channel requirements requested by Portland, Oregon, as a means to prevent the bridge's construction created the reason for such an imposing structure. Historian: Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., August 1993 LONGVIEW BRIDGE • HAER No. WA-89 (Page 2) History of the Bridge The Longview Bridge was built as part of an entrepreneurial dream to make the city of Longviev a thriving Columbia River port city. -

Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing

I NTERSTATE 5 C OLUMBIA R IVER C ROSSING Neighborhoods and Population Technical Report May 2008 TO: Readers of the CRC Technical Reports FROM: CRC Project Team SUBJECT: Differences between CRC DEIS and Technical Reports The I-5 Columbia River Crossing (CRC) Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) presents information summarized from numerous technical documents. Most of these documents are discipline- specific technical reports (e.g., archeology, noise and vibration, navigation, etc.). These reports include a detailed explanation of the data gathering and analytical methods used by each discipline team. The methodologies were reviewed by federal, state and local agencies before analysis began. The technical reports are longer and more detailed than the DEIS and should be referred to for information beyond that which is presented in the DEIS. For example, findings summarized in the DEIS are supported by analysis in the technical reports and their appendices. The DEIS organizes the range of alternatives differently than the technical reports. Although the information contained in the DEIS was derived from the analyses documented in the technical reports, this information is organized differently in the DEIS than in the reports. The following explains these differences. The following details the significant differences between how alternatives are described, terminology, and how impacts are organized in the DEIS and in most technical reports so that readers of the DEIS can understand where to look for information in the technical reports. Some technical reports do not exhibit all these differences from the DEIS. Difference #1: Description of Alternatives The first difference readers of the technical reports are likely to discover is that the full alternatives are packaged differently than in the DEIS. -

Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6

HHHIIISSSTTTOOORRRIIICCC CCCOOOLLLUUUMMMBBBIIIAAA RRRIIIVVVEEERRR HHHIIIGGGHHHWWWAAAYYY OOORRRAAALLL HHHIIISSSTTTOOORRRYYY FFFiiinnnaaalll RRReeepppooorrrttt SSSRRR 555000000---222666111 HISTORIC COLUMBIA RIVER HIGHWAY ORAL HISTORY Final Report SR 500-261 by Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., ODOT Senior Historian Amanda Joy Pietz, ODOT Research and Hannah Kullberg and Sara Morrissey, ODOT Interns Kristen Stallman, ODOT Scenic Area Coordinator Myra Sperley, ODOT Research Linda Dodds, Historian for Oregon Department of Transportation Research Section 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem OR 97301-5192 August 2009 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. OR-RD-10-03 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., ODOT Senior Historian; Amanda Joy Pietz, ODOT Research; and Hannah Kullberg and Sara Morrissey, ODOT Interns ; Kristen Stallman, ODOT Scenic Area Coordinator; Myra Sperley, ODOT Research; and Linda Dodds, Historian 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Oregon Department of Transportation Research Section 11. Contract or Grant No. 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem, OR 97301-5192 SR 500-261 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Oregon Department of Transportation Final Report Research Section 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem, OR 97301-5192 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract The Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History Project compliments a larger effort in Oregon to reconnect abandoned sections of the Historic Columbia River Highway. -

Engineering Geology in Washington, Volume I Wuhington Diviaion of Geology and Earth Resoul'ces Bulleti!I 78

The Cowlitz River Projects 264 ENGINEERING GEOLOGY IN WASHINGTON Aerial view of Mossyrock reservoir (Riffe Lake) and the valley of the Cowlitz River; view to the northeast toward Mount Rainier. Photograph by R. W. Galster, July 1980. Engineering Geology in Wuhington, Volume I . Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Bulletin 78 The Cowlitz River Projects: Mayfield and Mossyrock Dams HOWARD A. COOMBS University of Washington PROJECT DESCRIPTION unit) is at the toe of the dam on the north bank. The reservoir is 23.5 mi long. By impounding more than The Cowlitz River has its origin in the Cowlitz 1,600,000 acre-ft of water in the reservoir, the output of Glacier on the southeastern slope of Mount Rainier. The Mayfield Dam was greatly enhanced (Figures 3 and 4). river flows southward, then turns toward the west and passes through the western margin of the Cascade AREAL GEOLOGY Range in a broad, glaciated basin. It is in this stretch of The southern Cascades of Washington are composed the river that both Mossyrock and Mayfield dams are lo essentially of volcanic and sedimentary rocks that have cated. Finally, the Cowlitz River turns southward and been intruded by many dikes and sills and by small enters the Columbia River at Longview. batholiths and stocks of dioritic composition, as well as Mayfield Dam, completed in 1963, is 13 mi down plugs of andesite and basalt. Most of these rocks range stream from Mossyrock Dam, constructed 5 yr later. in age from late Eocene to Miocene (Hammond, 1963; Both are approximately 50 mi due south of Tacoma.