Oral History Interview – RFK #1, 12/15/1971 Administrative Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

^, ^^Tttism^" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> MAY � 1955 6� J�- W" �,V;Y,�.^4'>^, ^^Tttism^

..%:" -^v �^-*..: J^; SCOTT HALL AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY MAY � 1955 6� j�- w" �,v;y,�.^4'>^, ^^tttiSM^ Pat Gibson (Wisconsin) won her second successive National sen ior Women's skating title this past winter to become first woman in 54 years to turn the trick. Both years she achieved a perfect 150 point total, finishing first in five events. Head cheerleader at U.C.L.A. is Ruth Joos, Gamma Phi Beta. Chosen from 60 appli Allen Missouri Univer cants for the job, Ruth brings Audrey of as Orchid Ball queen of color and spirit to school ac sity reigned Delta Tau Delta. tivities, just as she engenders enthusiasm at the Alpha Iota ri* house. Representing Arizona as her Maid of Cotton in the National contest was Pat Hall of the University of Arizona. Pat was one of five finalists in the national. On campus, she served as freshman class treasurer. \a!!'ss�>-� :--- To climax Gamma Phi Beta week, Idaho State Collet' chapter enjoys annual Toga Dinner. "It's fun," they wr. \ "but three meals a day in this fashion could get prelly, tiresome: Queen of the King Kold Karnival at the University of North Dakota was Karen Sather. Gamma Phi iisters gather around to congratulate Karen (at far left) the night she won the queenship. They are (left to right) Patricia Kent. Falls Church, Va.; Jean Jacobson, Bismarck, N.D.; Mary Kate Whalen, Grand Forks, N.D.; De- lores Paulsen, Bismarck, N.D.; and Marion Day Herzer, Grand Forks, N.D. This Month's Front Cover THE CRESCENT Beautiful Scott Hall, across the quadrangle from the Gamma Phi Beta house, bears the name of former Northwestern Univer of Gamma Phi Beta sity President, Walter Dill Scott. -

Pioneerindex.Pdf

The following names are those who have been submitted to the WSGS Pioneer or First Citizen certificate program. The data was submitted by various people and there may be more than one submission for the same person. We only checked that the person was in the state prior to the cutoff for each kind of certificate. In the near future we will be offering a CD with the current data on it and as We receive new data it will be updated so that anyone purchasing the CD will always Get the latest information we have. *********************************************************************************** Henry Calvin ABEL b. 26 Jan 1833 Orange Co, IN James Ulysses ABEL b. 17 Nov 1865 Fremont, Mahaska Co, IA James ABERCROMBIE b. 1 Jan 1853 Chicago, IL Robert ABERNETHY b. 4 Aug 1852 Garderhouse, Sandsting, Shetland Is., SCT William ABRAMS b. 28 Dec 1836 ENG Elizabeth Virginia ACHEY b. 18 Apr 1889 Aberdeen, WT Louisa ACKLES b. 13 Dec 1838 OH Archibald ADAIR b. 25 Dec 1864 Balymather, Antrim, Northern IRL Alexander ADAIR b. 5 Jun 1829 Glasgow, SCT James Weir ADAIR b. 5 Jan 1858 West Rainton, ENG Valentine ADAM Sr b. 24 Aug 1845 Rhenish, Bavaria Charles Edward ADAMS b. 17 Nov 1831 Greenwich, CT Charles Francis ADAMS b. 8 Mar 1862 Baltimore, MD Edward Crossett ADAMS b. 4 Apr 1853 Alexandria, OH Elsie Hattie ADAMS b. 23 Feb 1890 Slaughter (now Auburn), King Co, WA Emma Dora ADAMS b. Douglas Co, OR Florence Emily ADAMS b. ca 1880 The Dalles, OR George Quincy ADAMS b. 2 Sep 1822 Wayne Co, PA Herman Heinrich ADAMS b. -

V Lhlailailliik*K^!^L

)t^-; \V-:-<i •> > -\;t -J , I '>'. •A ' ' i 5 : 5 . < i ; M ' Ml'j' i!'.' 'i?iH»* * ) . ' ' , I * 5 I . »'! 1-i r :^H^i:-v 1< \i W - * M ' ' ' ; ^i ' lHlailailliiK*K^!^l;l:(,l;s('!-':r:r:i>li:;' ' l4^l^ V :>'-'. » - 1 ,• '. n •Si' ! -1! '.';''.I'l fi^l .V'd sUn^i;':-! ' ' ' '. ' \ "t 1 ? ; , ' -. < < . :'Uv-^;-V^^.-"\^^'. • • < 3 I -. -. : .. V. : -, i <), A Jyay^i^. n Lp /c^y/^c-^ n ^2^ ^Z^ V c^ z^ ^-*-^-, ^2i^*/.^T^Y^-/^ yrVr lerfii- mmk mWim ^^^ <r At the Reunion of Carters at Woburn, Mass., June ii, 1884, a permanent organization was formed, which it is hoped will in due time be incorporated. The following was unanimously adopted as the COXSTITUTIOX. Article I. The name of the Association shall be The Carter Family Association. Article II. The object of the Association shall be the collection and pres- ervation of information respecting the histon.- of the Carter family. Article III. The officers shall be a President, two Vice-Presidents, a Corres- ponding Secretary, a Recording Secretary, and a Treasurer. Article IV. There shall be a Genealogical Commission, consisting of three members, who shall have power to add to their number. Article V. There shall be an Executive Committee, composed of the officers named in Article III. Article VI. Any descendant of the Carter lineage, of respectable standing in society, shall be eligible to membership and may become a mem- ber by signing the Roll of Membership (in person or by proxy), and by the payment of a fee of one dollar. Article VII. -

Reform and Reaction: Education Policy in Kentucky

Reform and Reaction Education Policy in Kentucky By Timothy Collins Copyright © 2017 By Timothy Collins Permission to download this e-book is granted for educational and nonprofit use only. Quotations shall be made with appropriate citation that includes credit to the author and the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University. Published by the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University in cooperation with Then and Now Media, Bushnell, IL ISBN – 978-0-9977873-0-6 Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs Stipes Hall 518 Western Illinois University 1 University Circle Macomb, IL 61455-1390 www.iira.org Then and Now Media 976 Washington Blvd. Bushnell IL, 61422 www.thenandnowmedia.com Cover Photos “Colored School” at Anthoston, Henderson County, Kentucky, 1916. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ item/ncl2004004792/PP/ Beechwood School, Kenton County Kentucky, 1896. http://www.rootsweb.ancestry. com/~kykenton/beechwood.school.html Washington Junior High School at Paducah, McCracken County, Kentucky, 1950s. http://www. topix.com/album/detail/paducah-ky/V627EME3GKF94BGN Table of Contents Preface vii Acknowledgements ix 1 Reform and Reaction: Fragmentation and Tarnished 1 Idylls 2 Reform Thwarted: The Trap of Tradition 13 3 Advent for Reform: Moving Toward a Minimum 30 Foundation 4 Reluctant Reform: A.B. ‘Happy” Chandler, 1955-1959 46 5 Dollars for Reform: Bert T. Combs, 1959-1963 55 6 Reform and Reluctant Liberalism: Edward T. Breathitt, 72 1963-1967 7 Reform and Nunn’s Nickle: Louie B. Nunn, 1967-1971 101 8 Child-focused Reform: Wendell H. Ford, 1971-1974 120 9 Reform and Falling Flat: Julian Carroll, 1974-1979 141 10 Silent Reformer: John Y. -

Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1987 Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963 John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963" (1987). Political History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/3 Divide and Dissent This page intentionally left blank DIVIDE AND DISSENT KENTUCKY POLITICS 1930-1963 JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2006 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Qffices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pearce,John Ed. Divide and dissent. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kentucky-Politics and government-1865-1950. -

Statement, June 1978

MOREHEAD STATE!NjJ~fl)Jl: People, Programs and Progress at Morehead State Univers ity Vol. 1, N o. 5 M orehead, Ky. 4035 1 June, 1978 To find,get and hold a job It's official name is the "employability skil ls project" Essential ly, the program teaches individuals to use but to the growing number of persons benefiting from various sources of job information, to plan personal and Morehead State University's newest regional service vocational goals, to effectively present themselves to effort, it is the "job course." prospective employers and to develop good work habits. In simple terms, its purpose is to help Kentuckians Since its beginning last fall under a grant from the choose, f ind, get and keep a job of their choice. It is the U.S. Office of Education, the program has enrolled 170 first program of MSU's new Appalachian Development students at 10 locations, including Morehead, Mt. Center and, if the growing demand for the instruction is Sterling, Ashland, Lexington, Louisville and Beattyville. an indication of success, the "job course" is on target. The Lexington and Louisville classes were required by ''Our goal is to help our people be more competitive the funding agency for comparative purposes. in today's job market," said Gary Wilson, project The project utilizes the Adkins Life Skills Program, a coordinator and one of three instructors. "Our clientele series of 10 units of instruction developed by Dr. Win range from high school and college students to senior Adkins of Columbia University. Refined over a citizens but all have determined that they need to seven-year period, the program uses a multi-media improve t heir job-related skills." approach and other teaching techniques. -

01A-Front Page

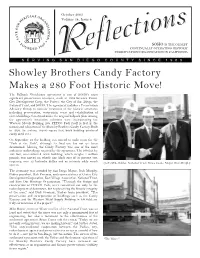

October 2003 Volume 34, Issue 4 Showley Brothers Candy Factory Makes a 280 Foot Historic Move! The Ballpark Warehouse agreement is one of SOHO's most significant preservation triumphs, made in 1999 between Centre City Development Corp., the Padres, the City of San Diego, the National Trust, and SOHO. The agreement includes a Preservation Advisory Group to monitor treatment of the historic structures including preservation, restoration, reuse and rehabilitation of eleven buildings threatened under the original ballpark plan. Among the agreement’s innovative solutions were incorporating the Western Metals Building into PETCO Park itself (a first in the nation) and relocation of the Showley Brothers Candy Factory. Built in 1924, the 3-story, 30,000 square foot, brick building produced candy until 1951. On September 22 the building was moved to make room for the "Park at the Park", although its final use has not yet been determined. Moving the Candy Factory was one of the most ambitious undertakings required by the agreement. The 100 foot by 100 foot, un-reinforced brick building, which weighs 3 million pounds, was moved on wheels one block east of its present site, requiring over 42 hydraulic dollies and an intricate cable winch (L-R) Mike Buhler, National Trust, Bruce Coons, Mayor Dick Murphy system. The ceremony was attended by San Diego Mayor, Dick Murphy, Padres president, Dick Freeman, and representatives of Centre City Development Corporation, East Village Association, National Trust, and Save Our Heritage Organisation. "Through the design and construction of PETCO Park, we’re committed not only to the redevelopment of downtown, but to preserving the historic integrity of the area," said Dick Freeman, Padres team president. -

The Papers of WEB. Du Bois

The Papers of WEB. Du Bois A Guide by Robert W McDonnell Microfilming Corporation of America A Newh-kTitiws Conipany I981 !NO part of this hook may be reproduced In any form, by Photostat, lcrofllm, xeroqraphy, or any other means, or incorporated into bny iniarmriion ~vtrievrisystem, elect,-onic 01 nwchan~cnl,without the written permission of thc copirl-iqht ownpr. Lopyriqht @ 1481. 3nlversi iy of Mr+sictl~lirtt.~dt AnlhC:~st ISBN/O-667-00650- 8 Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biographical Sketch Scope and Content of the Collection Uu Bois Materials in Other Repositories X Arrangement of the Collection xii Descriptions of the Series xiii Notes on Arrangement of the Collection and Use of the Selective xviii Item List and Index Regulations for Use of W.E.B. Du Bois Microfilm: Copyright Information Microfilm Reel List Selective Item List Selective Index to (hide- Correspondence ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The organization and publication of the Papers of W.E.B. Du Bois has been nade possible by the generous support of the National Endownrent for the Humanities and the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the ever-available assistance of their expert staffs, eipecially Margaret Child and Jeffrey Field for NEH and Roger Bruns, Sara Jackson, and George Vogt for NHPRC. The work was also in large part made possible by the continuing interest, assis- tance, and support of Dr. Randolph Broniery, Chancellor 1971-79, dnd Katherine Emerson, Archivist, of the University of MassachusettsiAmherst, and of other members of the Library staff. The work itself was carried out by a team consisting, at various times, of Mary Bell, William Brown, Kerry Buckley, Carol DeSousa, Candace Hdll, Jbdith Kerr, Susan Lister, Susan Mahnke, Betsy McDonnell, and Elizabeth Webster. -

CHAPTER XIII GENEALOGICAL TABLES EXPLANATION the Progenitors of the Baltic Family in America, So Far As Is Known, Were John Batt

CHAPTER XIII GENEALOGICAL TABLES EXPLANATION The progenitors of the BaltIc family in America, so far as is known, were John Battle and Mathew Battle (probably John's brother). In the following Tables are gil'en, as far as they could be procured, the names of all their descend ants, with such facts about each as seemed most worth selling down. Tables 1-78 give the descendants of John, Tables 7'1--87 those of Mathew. The inset key shows the relation of the Tables. The reference under the names hending a Table shows the previous Table in which the descent of the first name may be traced. For example, in Table 10 under the heading Henr!l Laure1ls Battle etc. the reference, See Table 9, means that Henry Laurens Battle's dcscent may bt' traced in Table 9. The letter and numbers before the first name of a Table sl;ow the manner of descent from John or Mathew Battle. For example, in Table 10, J. 1. 2. 6. S. S. 7. Henr!l Laurens Battle means that Henry Laurens Battle was the seventh child of the third child of the third child of the sixth child of the second child of the first child of John Battle. Similarly in Table 79, M. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 5. Nicholas JVilliam Bat tle means that Nicholas William Battle was the fifth child of the first child of the first child of the first child of the first child of the first child of Mathew Battle. After the first name of each Table are given, where pOSSible, present or last place of residence, occupation, placc and date of birth, place and date of death, manner of education, items of special interest, religious affiliation, place and date of marriage, name of husband or wife with, in parenthesis, the place and date of birth an~ death of that husband or wife and the names of the parents. -

(Kentucky) Democratic Party : Political Times of "Miss Lennie" Mclaughlin

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-1981 The Louisville (Kentucky) Democratic Party : political times of "Miss Lennie" McLaughlin. Carolyn Luckett Denning 1943- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Denning, Carolyn Luckett 1943-, "The Louisville (Kentucky) Democratic Party : political times of "Miss Lennie" McLaughlin." (1981). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 333. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/333 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LOUISVILLE (KENTUCKY) DEMOCRATIC PARTY: " POLITICAL TIMES OF "MISS LENNIE" McLAUGHLIN By Carolyn Luckett Denning B.A., Webster College, 1966 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Political Science University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 1981 © 1981 CAROLYN LUCKETT DENNING All Rights Reserved THE LOUISVILLE (KENTUCKY) DEMOCRATIC PARTY: POLITICAL TIMES OF "MISS LENNIE" McLAUGHLIN By Carolyn Luckett Denning B.A., Webster College, 1966 A Thesis Approved on <DatM :z 7 I 8 I By the Following Reading Committee Carol Dowell, Thesis Director Joel /Go]tJstein Mary K.:; Tachau Dean Of (j{airman ' ii ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to examine the role of the Democratic Party organization in Louisville, Kentucky and its influence in primary elections during the period 1933 to 1963. -

An AMAZING the Day After Her Graduation

THE MOUNTAIN EAGLE, WHITESBURG, KENTUCKY THURSDAY, MAY 24, 1954 Stauffer, Mrs. Oscar Parks, and Woman's Civic Club of Jenkins Conducts Mrs. A. C. Dittrick. Special guest was Mrs. P. E. Sloan, Annual Installation Of Officers For Club Whitesburg. High prize was pre sented to Mrs. J. M. Stauffer, guest prize to Mrs. P. E. Sloan. LET'S CONTINUE KENTUCKY'S LEADERSHIP In an impressive ceremony, monthly bulletins; Mr. George Mrs. Vernoy Tate, of the Wise, O. Tarleton, Sr., president of T nrrw Tnnnuv .TpnWnc TTiffh I Virginia, Woman's Club, con- Consolidation, who has consist School graduate, Class of '55, IN THE UNITED STATES SENATE ducted the annual installation ently lent a hand to the Club in was initiated into the Kappa Iota of officers service of the Wo- whatever capacity was needed, Epsilon honor society for soph man's Civic Club of Jenkins, and who arranged for addition- at omore men, Eastern State C. Clements man who is and Now it is up to YOU, the people, to decide at the close of a dinner pro- al shelves to be built in the College on May 9th. Require Earle is a Mc-- appre- gram held in the large dining library this year; Mr. Russell ments for this honor are out always has been deeply interested in and ifthis man has the experience, the Donough, work room of The Inn at Wise, Sat- for his faithful standing leadership and responsive to all Kentuckiana. His life is ciation of Kentucky's needs, the character urday night, May 19. and help each year at carnival dedicated to you, people. -

SOHO Reflections Newsletter, Vol. 13, Issue 5

THE S.0.H.0. NEWSLETTER REFLECTIONS MAY 1981 P.O. BOX 3571 SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA 92103 NATIONAL PRESERVATION WEEK MAY 10-16 "Conservation: Keeping America's Neighborhoods Together" is the theme of National Historic Preservation Week, May 10-16, 1981 and is being cosponsored by S.O.H.O. and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, in San Diego. The purpose of Preservation Week's theme is to promote a working alliance between neighborhood leaders and preservation activists. Approximately 5,000 preservation and neighborhood groups are expected to cosponsor simultaneous Preservation Week events in their communities throughout the country. In San Diego, S.O.H .O. will be sponsoring a tour, starting on Second Avenue and Maple in the Uptown -Middletown area. The tour will be on May 17. For more information, call 297-9327. The ninth annual observance of Preservatio·n Week provides the opportunity to showcase the 'valuable exchange possible between preservation and neighborhood conservation: neighborhood conservation offers the preservation community a major opportunity to save countless numbers of older buildings; preservation offers neighborhood conservation tools for building community pride and interest as well as methods for saving neighborhood landmarks. S.O.H.O. is proud to join in the national celebration of preservation by recognizing unique examples of architecture in the neighborhoods of "America's Finest City." ~ ·MAY f :ii,i-<GULUTr : ZEHBE Tuesday, ifay 5 Historical Site Board 1 y.m. 5th Floor Conference Room City Administration Building SGi:UA F'. Jv~ ~E.S Thursday, day 7 SOHOBoard Meeting KATHYT Rt:.r'fY 7:30 p.rr:.