EARLY MODERN ITALY a Comprehensive Bibliography of Works In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guida-IRO.Pdf

The Head of Dipartimento di Economia e Management Dear students, Welcome to the Dipartimento di Economia e Management! Our Department is a lively environment where research and teaching live side by side in the areas of economics, business and management studies, mathematics and statistics. Moreover, courses on legal theory and foreign languages applied to economics are provided. In recent years, the Department has particularly increased its international activities, achieving very good results. We have created an International Relations Office, we have more than doubled the number of exchange students and exchange opportunities (Erasmus and overseas), and we have developed an International Programme for undergraduates and graduates, a MSc in Economics and an MBA totally taught in English, and many other international activities. In coming years, we aim to expand the opportunities for studying business, strategy, and marketing in English. This has a double aim: intensify the presence of foreign students in our Department and stimulate our students to live and work in an international context. I hope you will enjoy your stay in Pisa. Prof. Bianchi Martini Index 1. Welcome to Pisa . Welcome to Pisa pag. 6 . How to get to Pisa pag. 7 . A brief history of Pisa pag. 8 . The town and its surroundings pag. 11 . A short tour of Pisa pag. 13 2. IRO International Relations Office . Where we are pag. 18 . Purposes of IRO pag. 19 . International office services pag. 20 3. Academic information . Academic calendar pag. 26 . Study plan pag. 27 . CFU and ECTS credits pag. 28 . Italian marks pag. 29 . How to apply for exams pag. -

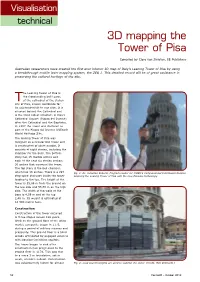

3D Mapping the Tower of Pisa

Visualisation technical 3D mapping the Tower of Pisa Compiled by Clare van Zwieten, EE Publishers Australian researchers have created the first ever interior 3D map of Italy’s Leaning Tower of Pisa by using a breakthrough mobile laser mapping system, the ZEB 1. This detailed record will be of great assistance in preserving the cultural heritage of the site. he Leaning Tower of Pisa is the freestanding bell tower, Tof the cathedral of the Italian city of Pisa, known worldwide for its unintended tilt to one side. It is situated behind the Cathedral and is the third oldest structure in Pisa's Cathedral Square (Piazza del Duomo) after the Cathedral and the Baptistry. In 1987 the tower was declared as part of the Piazza del Duomo UNESCO World Heritage Site. The leaning Tower of Pisa was designed as a circular bell tower and is constructed of white marble. It consists of eight stories, including the chamber for the bells. The bottom story has 15 marble arches and each of the next six stories contain 30 arches that surround the tower. The top story is the bell chamber, which has 16 arches. There is a 297 Fig. 1: Dr. Jonathan Roberts, Program Leader for CSIRO's Computational Informatics Division step spiral staircase inside the tower scanning the Leaning Tower of Pisa with the new Zebedee technology. leading to the top. The height of the tower is 55,86 m from the ground on the low side and 55,70 m on the high side. The width of the walls at the base is 4,09 m and at the top 2,48 m. -

Florence Florence Can Boast Many Histories – Artistic, Financial, Religious, the Central Point of the City’S Political and Cultural Development

AGENZIA PER IL TURISMO FIRENZE florence Florence can boast many histories – artistic, financial, religious, the central point of the city’s political and cultural development. cultural, political. These are so rich that it is impossible to sum By virtue of its geographic position and social climate, Florence them up in a few short lines. One word, however, has always dis- exercised a function of equilibrium in the history and art of the pe- tinguished the city in the eyes of the world: the Renaissance. riod known as the Renaissance. After various vicissitudes involving the Florentine Republic and history Medici restorations, another historic era started for Florence in a brief 1530 with the establishment of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. The The early Etruscan settlements sprang up on the hill of Fiesole, power of the city grew, reaching a peak with the defeat of arch-ri- while the Romans established themselves (in 59 BC) on the plain val Siena in 1555. The House of the Medici died out in the 18th around the Arno. The Forum of Roman Florentia was situated where century, giving way to the rule of the Habsburg-Lorraine, under Piazza della Republica stands today, and the inner circle of walls whom Florence also conquered Lucca (1847). Finally, the Duchy ran along today’s Via Tornabuoni, Via Cerretani and Via del Pro- entered the Kingdom of Italy in 1859 following a plebiscite. consolo. Florence was the capital of unified Italy from 1865 to 1870, dur- Miniato and Reparata were the first patron saints of Florence, ing which time Giuseppe Poggi produced an urban planning proj- which became an episcopal see in the 4th century. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2c73n9k4 Author Boyle, Michael Shane Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence By Michael Shane Boyle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair Professor Anton Kaes Professor Shannon Steen Fall 2012 The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence © Michael Shane Boyle All Rights Reserved, 2012 Abstract The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance After the Age of Affluence by Michael Shane Boyle Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair While much humanities scholarship focuses on the consequence of late capitalism’s cultural logic for artistic production and cultural consumption, this dissertation asks us to consider how the restructuring of capital accumulation in the postwar period similarly shaped activist practices in West Germany. From within the fields of theater and performance studies, “The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence” approaches this question historically. It surveys the types of performance that decolonization and New Left movements in 1960s West Germany used to engage reconfigurations in the global labor process and the emergence of anti-imperialist struggles internationally, from documentary drama and happenings to direct action tactics like street blockades and building occupations. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

The Commune Movement During the 1960S and the 1970S in Britain, Denmark and The

The Commune Movement during the 1960s and the 1970s in Britain, Denmark and the United States Sangdon Lee Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2016 i The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement ⓒ 2016 The University of Leeds and Sangdon Lee The right of Sangdon Lee to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 ii Abstract The communal revival that began in the mid-1960s developed into a new mode of activism, ‘communal activism’ or the ‘commune movement’, forming its own politics, lifestyle and ideology. Communal activism spread and flourished until the mid-1970s in many parts of the world. To analyse this global phenomenon, this thesis explores the similarities and differences between the commune movements of Denmark, UK and the US. By examining the motivations for the communal revival, links with 1960s radicalism, communes’ praxis and outward-facing activities, and the crisis within the commune movement and responses to it, this thesis places communal activism within the context of wider social movements for social change. Challenging existing interpretations which have understood the communal revival as an alternative living experiment to the nuclear family, or as a smaller part of the counter-culture, this thesis argues that the commune participants created varied and new experiments for a total revolution against the prevailing social order and its dominant values and institutions, including the patriarchal family and capitalism. -

Gesualdo Madrigaux Livre I Solistes Des Arts Florissants Paul Agnew

AMPHITHÉÂTRE – CITÉ DE LA MUSIQUE Gesualdo Madrigaux Livre I Solistes des Arts Florissants Paul Agnew Mardi 23 octobre 2018 – 20h30 Concert enregistré par France Musique. Ce concert est diffusé en direct sur le site internet live.philharmoniedeparis.fr où il restera disponible pendant 4 mois. PROGRAMME Carlo Gesualdo (1566-1613) Ne reminiscaris Domine Luzzasco Luzzaschi (1545-1607) Dolorosi martir, fieri tormenti Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) Baci soavi, e cari Luca Marenzio (1553-1599) Baci soavi, e cari (Prima parte) Baci amorosi, e belli (Seconda parte) Baci affamati, e ‘ngordi (Terza parte) Baci cortesi, e grati (Quarta parte) Baci, ohimè, non mirate (Quinta & ultima parte) Carlo Gesualdo Tribulationem et dolorem Hei mihi domine Luca Marenzio Tirsi morir volea (Prima parte) Frenò Tirsi il desio (Seconda parte) Così moriro i fortunati amanti (Terza parte) 3 Benedetto Pallavicino (1551-1601) Tirsi morir volea (Prima parte) Frenò Tirsi il desio (Seconda parte) Così moriro i fortunati amanti (Terza parte) ENTRACTE Carlo Gesualdo Baci soavi e cari Quant’ha di dolce Amore (Seconda parte) Madonna, io ben vorrei Com’esser può ch’io viva se m’uccidi? Gelo ha Madonna il seno, e fiamma il volto Mentre Madonna il lasso fianco posa Ahi, troppo saggia nell’errar (Seconda parte) Se da sì nobil mano Amor, pace non chero (Seconda parte) Sì gioioso mi fanno i dolor miei O dolce mio martire Tirsi morir volea Frenò Tirsi il desio (Seconda parte) Mentre, mia stella, miri Non mirar, non mirare Questi leggiadri odorosetti fiori Felice primavera Danzan -

Gesualdo Paul Agnew Madrigali Libri Primo & Secondo FRANZ LISZT CARLO GESUALDO (1566-1613) Madrigali a Cinque Voci

Les Arts Florissants Gesualdo Paul Agnew MADRIGALI LIBRI PRIMO & SECONDO FRANZ LISZT CARLO GESUALDO (1566-1613) MADRIGALI A CINQUE VOCI CD 1 Libro primo (Ferrara, 1594) 1 | Baci soavi, e cari. Giovanni Battista Guarini. Rime amorose Prima parte 2 | Seconda parte: Quant’ha di dolce Amore 2’31 3 | Madonna, io ben vorrei. Incerto MA, MR, SC, PA, EG 3’00 4 | Com’esser può ch’io viva se m’uccidi? Incerto MA, HM, MR, PA, EG 2’12 5 | Gelo ha Madonna il seno. Torquato Tasso, Rime HM, MR, PA, SC, EG 2’07 6 | Mentre Madonna il lasso fianco posa. Torquato Tasso, Rime MA, MR, SC, PA, EG 2’14 Prima parte 7 | Seconda parte: Ahi, troppo saggia nell’errar. 2’10 8 | Se da sì nobil mano. Torquato Tasso, Rime HM, MR, PA, SC, EG 1’54 Prima parte 9 | Seconda parte: Amor, pace non chero 1’27 10 | Sì gioioso mi fanno i dolor miei. Luigi Cassola HM, MA, MR, SC, EG 2’44 11 | O dolce mio martire. Incerto MA, MR, SC, PA, EG 2’27 12 | Tirsi morir volea. Battista Guarini, Rime HM, MR, PA, SC, EG 2’19 Prima parte 13 | Seconda parte: Frenò Tirsi ’l desio 2’45 14 | Mentre, mia stella, miri. Torquato Tasso MA, MR, SC, PA, EG 2’16 15 | Non mirar, non mirare. Filippo Alberti MA, HM, MR, PA, EG 2’21 16 | Questi leggiadri odorosetti fiori. Livio Celiano (alias Angelo Grillo) HM, MR, PA, SC, EG 2’50 17 | Felice primavera. Torquato Tasso MA, MR, SC, PA, EG 1’32 Prima parte 18 | Seconda parte: Danzan le ninfe honeste, e i pastorelli 1’26 19 | Son sì belle le rose. -

Newsletter.05

College of L e t t e r s & S c i e n c e U n i v e r s i t y D EPARTMENT o f of California B e r k e l e y MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE Alumni Newsletter S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 5 September 2005 D EAR A LUMNI AND F RIENDS , Note from the Chair reetings to all from the PEOPLE 1–3Update on the last 4 years GUniversity of California, ince the last newsletter, Wye Allanbrook Berkeley, Department of Music, Scompleted her term as department chair, Centenary Celebration this year celebrating our 100th having contributed enormous effort on 100 years of music at Cal birthday! (See article below.) behalf of the new Hargrove Music Library 1, 8–9 This newsletter has always Bonnie Wade building. For the past two years, she has Faculty News Creative accomplishments, been intended as an occasional publication been a Fellow at the National Humanities honors & awards, new to bring to you news of the department. Center in North Carolina. She returns to 4arrivals– Melford6 & Midiyanto For comprehensive details and regular teaching in the 2005–06 academic year. updates please visit our websites: http:// In fall 2003, Allanbrook was succeeded music.berkeley.edu (department); www. by Anthony Newcomb, who served as Gifts to the Department lib.berkeley.edu/MUSI (music library); and department chair for two years. After a 6 www.cnmat.berkeley.edu (Center for New long and distinguished career as teacher Music and Audio Technologies, CNMAT). -

Antwerp in 3 Days | the Rubens House

Antwerp in 3 days | The Rubens House Rubens was a man of many talents. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and an architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? Rubens as an architect When Rubens returned from Italy in 1608, at the age of 31, he came back with a case full of sketches and a head full of ideas. He purchased a plot of land with a house near his grandfather’s home (Meir 54) and converted it into his own Palazzetto. Take an hour to visit the Rubens House and to breathe in the atmosphere in the master’s house before setting off to explore his city. Rubens’s palazzetto on the Wapper was not yet complete when the artist was commissioned to work on the Baroque Jesuit church some distance away, at Hendrik Conscienceplein. The St Carolus Borromeus Church at Hendrik Conscienceplein is the epitome of Italian grandeur. With his knowledge of Italian architecture, Rubens undoubtedly contributed ideas for the façade, but his greatest achievements here are to be seen in the interior. Rubens designed the richly decorated chapel and its impressive marble high altar. Sadly, all that remains of the master’s 39 ceiling paintings are the sketches that are preserved in the church. The paintings themselves perished in a huge fire in 1718. The high altar merits particular attention: behind the enormous painting – it measures 4.0 x 5.35 metres – other works are concealed. -

Paolo Veroneses Art of Business

Paolo Veronese’s Art of Business: Painting, Investment, and the Studio as Social Nexus Author(s): John Garton Reviewed work(s): Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 65, No. 3 (Fall 2012), pp. 753-808 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Renaissance Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/668301 . Accessed: 02/10/2012 14:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Renaissance Society of America are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Renaissance Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org Paolo Veronese’s Art of Business: Painting, Investment, and the Studio as Social Nexus* by J OHN G ARTON Despite the prominent career of Paolo (Caliari) Veronese (1528 –88), much remains to be discovered about his patrons and peers. Several letters written by the artist are presented here for the first time, and their recipient is identified as the humanist Marcantonio Gandino. The letters reference artworks, visitors to Veronese’s studio, and economic data pertaining to the painter. Analyzing the correspondence from a variety of methodological viewpoints reveals how Veronese fulfilled commissions, interacted with nobility, and invested his painterly profits in land on the Venetian terraferma. -

Bernini and Other Studies in the History Of

Ki CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE FINE ARTS DATE DUE Cornell University Library N "l^r-7H| \<^ 7445.N88 Bernini and other studies in ttie history 4891- 3 1924 020 704 122 'gi-^^^a Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924020704122 BERNINI AND OTHER STUDIES THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON - CHICAGO • DALLAS ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO V' ,/<? «^ !A8i Plate I. BERNINI AND OTHER STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ART BY RICHARD NORTON MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON THE MACMILLAN COMPANY LONDON: MACMILLAN AND COMPANY 1914 All rights reserved s H Hit rf4 -a^ COPTBIGHT, 1914, By the MACMILLAN COMPANY. Set up and electrotyped. Published October, 1914. Norinodli ^teiss J, S. Onshing Go. — Berwick & Smith Go. Norwood, Mass., U.S.A. PREFACE The essays presented in the following pages are the prod- uct of no hasty thought. I am grateful to the kind friends who have encouraged their publication, and to the publishers for giving them so attractive a form. The choice of illustrations has been difficult. It has seemed best, however, to reproduce in full the little-known sketches of Bernini showing the development, in his mind, of the design for the Piazza of St. Peter's, and the sculptor's models wrought by his own hands.