Fake News Attributions As a Source of Nonspecific Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Most Censored Publication in History Daily Stormer Sunday Edition

Publishing online Now in print since 2013, because the offline & Tor (((internet))) is since 2017. censorship! StormerThe most censored publication in history Vol. 92, 19–26 May 2019 Daily Stormer Sunday Edition Samizdat! Follow Andrew Anglin on GAB for the latest news and site updates: https://gab.ai/AndrewAnglin Surface web: dailystormer.name Deep web: dstormer6em3i4km.onion The Daily Stormer is non-profit and 100% reader- Daily Stormer’s Bitcoin address: supported. We do what we do because we are attempting 19m9yEChBSPuzCzEMmg1dNbPvdLdWA59rS to preserve Western Civilization. We do it out of love. Because the website and this Sunday Edition are not mone- tized, we require contributions from readers to pay the ex- penses involved. PayPal (and everything else known to man) has banned this site and me as an individual person from using their ser- vices, so right now all we have is bitcoin. Sunday Edition BTC: 1NsNmzzXtqiZ4YStnYWaEgCauWBGBs2iqB 2 Daily Stormer ̈ Sunday Edition Vol. 92 Publishing daily at: dstormer6em3i4km.onion BTC: 19m9yEChBSPuzCzEMmg1dNbPvdLdWA59rS Vol. 92 Daily Stormer ̈ Sunday Edition 3 relevant truth to human life is that nothing is free. Sections Everything has a price. Not nec- Featured Stories 3 essarily money. Not even usually World News 26 money. You trade one thing for an- other. Sometimes these trades are United States 58 good trades, sometimes they are not Jewish Problem 88 so good trades, like in that Stephen Race War 100 King book “Needful Things.” But you Society 112 always get what you pay for. Insight 127 Featured Stories I saw a post the other day from a woman talking about how when she was 21 and pregnant with a toddler running around, she was seeing her friends from high school on Face- Self-Help Sunday: Nothing is book posting pictures of their college parties and trips around the world, Free and she felt like she was missing out. -

Conversations with Bill Kristol

Conversations with Bill Kristol Guest: Jonathan Rauch, Author, Journalist, Senior Fellow Brookings Institution Taped June 17, 2021 Table of Contents I. Polarization and Disinformation (0:15 – 33:00) II: Cancel Culture and Illiberalism (33:00 – 1:21:25) I. Polarization and Disinformation (0:15 – 33:00) KRISTOL: I am Bill Kristol. Welcome to CONVERSATIONS, and I'm very pleased to be joined today by Jonathan Rauch, a longtime friend and someone I've admired a lot and very much looking forward to hearing from. Author of an excellent new book. I should hold this up here, that's what you're supposed to do, The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth, published by the Brookings Institution where he's a senior fellow. In a way this book, John, I think is a follow-up to a book you wrote, God, it's hard to believe almost three decades ago, Kindly Inquisitors: Attacks on Free Thought, which I remember well reading at the time. So, John, thanks for joining me today. RAUCH: It's a special pleasure. I love the podcast and your father helped me with the Kindly Inquisitors at AEI all those years ago. So this, in that way, closes the circle. KRISTOL: Oh, that's great. I didn't know that, so that's good. That's good to hear. You also wrote an excellent piece last year, I thought — I might just begin with that for a couple of minutes before getting into the things you particularly focus on in the book — in National Affairs, I think was about a year ago, two years ago, I guess, on polarization and partisanship. -

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: W. Lance Bennett, Chair Matthew J. Powers Kirsten A. Foot Adrienne Russell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication University of Washington Abstract The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: W. Lance Bennett Department of Communication Democracy in America is threatened by an increased level of false information circulating through online media networks. Previous research has found that radical right media such as Fox News and Breitbart are the principal incubators and distributors of online disinformation. In this dissertation, I draw attention to their political mobilizing logic and propose a new theoretical framework to analyze major radical right media in the U.S. Contrasted with the old partisan media literature that regarded radical right media as partisan news organizations, I argue that media outlets such as Fox News and Breitbart are better understood as hybrid network organizations. This means that many radical right media can function as partisan journalism producers, disinformation distributors, and in many cases political organizations at the same time. They not only provide partisan news reporting but also engage in a variety of political activities such as spreading disinformation, conducting opposition research, contacting voters, and campaigning and fundraising for politicians. In addition, many radical right media are also capable of forming emerging political organization networks that can mobilize resources, coordinate actions, and pursue tangible political goals at strategic moments in response to the changing political environment. -

How to Get the Daily Stormer Be Found on the Next Page

# # Publishing online In print because since 2013, offline Stormer the (((internet))) & Tor since 2017. is censorship! The most censored publication in history Vol. 99 Daily Stormer ☦ Sunday Edition 07–14 Jul 2019 What is the Stormer? No matter which browser you choose, please continue to use Daily Stormer is the largest news publication focused on it to visit the sites you normally do. By blocking ads and track- racism and anti-Semitism in human history. We are signifi- ers your everyday browsing experience will be better and you cantly larger by readership than many of the top 50 newspa- will be denying income to the various corporate entities that pers of the United States. The Tampa Tribune, Columbus Dis- have participated in the censorship campaign against the Daily patch, Oklahoman, Virginian-Pilot, and Arkansas Democrat- Stormer. Gazette are all smaller than this publication by current read- Also, by using the Tor-based browsers, you’ll prevent any- ership. All of these have dozens to hundreds of employees one from the government to antifa from using your browsing and buildings of their own. All of their employees make more habits to persecute you. This will become increasingly rele- than anyone at the Daily Stormer. We manage to deliver im- vant in the years to come. pact greater than anyone in this niche on a budget so small you How to support the Daily Stormer wouldn’t believe. The Daily Stormer is 100% reader-supported. We do what Despite censorship on a historically unique scale, and The we do because we are attempting to preserve Western Civiliza- Daily Stormer becoming the most censored publication in his- tion. -

December 13, 2019 Order

Case 4:18-cv-00442-ALM-CMC Document 80 Filed 12/13/19 Page 1 of 33 PageID #: 1260 United States District Court EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS SHERMAN DIVISION ED BUTOWSKY, § Plaintiff, § § V. § Civil Action No. 4:18CV442 § Judge Mazzant/Magistrate Judge Craven DAVID FOLKENFLIK, ET AL., § Defendants. § ORDER The above-referenced cause of action was referred to the undersigned United States Magistrate Judge for pretrial purposes in accordance with 28 U.S.C. § 636. The following motion is before the Court: Plaintiff’s Motion to Compel Federal Bureau of Investigation to Comply with Subpoena Duces Tecum (Docket Entry # 75). The Court, having carefully considered the relevant briefing, is of the opinion the motion should be DENIED. I. BACKGROUND This is an action for defamation per se, business disparagement, and civil conspiracy filed by Plaintiff Ed Butowsky (“Plaintiff” or “Butowsky”), a Dallas investment advisor, against National Public Radio, Inc. (“NPR”), its senior media correspondent, David Folkenflik (“Folkenflik”), and certain former and current executive editors at NPR (Edith Chapin, Leslie Cook, and Pallavi Gogoi, jointly and severally) (collectively, “Defendants”). According to Plaintiff, Defendants published false and defamatory statements about Plaintiff online and via Twitter between August 2017 and March 2018 – statements Plaintiff alleges injured his business and reputation. Docket Entry # 72, ¶ 5. Defendants contend Plaintiff filed suit against Case 4:18-cv-00442-ALM-CMC Document 80 Filed 12/13/19 Page 2 of 33 PageID #: 1261 them for accurately reporting on a publicly filed lawsuit on a matter of public concern. Specifically, Defendants assert Plaintiff filed suit following NPR’s reporting on a 2017 lawsuit filed by Fox News contributor Rod Wheeler against Fox News. -

Arianators Assemble the Teen Fans Weaving a Web of Support

Thursday 25.05.17 12A Symbol of defi ance ofdefi Symbol bee Manchester’s Morrissey’s hate Morrissey’s Suzanne Moore of support aweb weaving fans The teen assemble Arianators Taste tested Taste Croissants! Sgt Pepper art Pepper Sgt Chicago Judy Shortcuts Symbolism Why the bee is a perfect symbol Seen in Manchester … a card left after the for Manchester terror attack, graffiti on a gate, a bee tattoo and a city bollard rom homemade banners F and badges to images of mosaics, cartoons and T-shirts posted online, one symbol has come to defi ne Manchester’s togetherness following Monday night’s terror attack: the worker bee. But, as even Mancunians may be asking, why ? Offi cially, bees have been part of the city’s identity since 1842 , when a new city coat of arms was unveiled which, in part, depicts bees swarming across the globe. This represented the industriousness of the “worker bees” then toiling in Manchester’s cotton mills, colloquially known as beehives. What Manchester’s impover- ished, slum-dwelling workers thought of this depiction is not recorded. The Co-operative Movement used beehives as a positive symbol of solidarity , but logo , on the clock face at the bespoke litter bins with a honey- What happened this week, that city crest must surely have Victorian Palace hotel , even comb design and luminescent bee however, embodies Manchester’s felt somewhat patronising in this referenced, obliquely, in the black logo . Suddenly, the bee was fl eet, instinctive creativity. From then hotbed of Chartist revolt. and gold trim of Manchester everywhere, and, gradually, it factory chimneys to bucket hats, A city which, via a roll call of City’s 2009/10 away kit . -

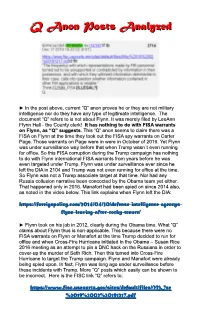

Q Anon Posts Analyzed

QQ AnonAnon PostsPosts AnalyzedAnalyzed ► In the post above, current “Q” anon proves he or they are not military intelligenceintelligence nornor dodo theythey havehave anyany typetype ofof legitimatelegitimate intelligence.intelligence. TheThe document “Q” refers to is not about Flynn. It was merely filed by LeeAnn Flynn Hall - the County clerk! It has nothing to do with FISA warrants on Flynn, as “Q” suggests. This “Q” anon seems to claim there was a FISA on Flynn at the time they took out the FISA spy warrants on Carter Page. Those warrants on Page were in were in October of 2016. Yet Flynn was under surveillance way before that when Trump wasn´t even running for office. So this FISA corruption during the Trump campaign has nothing to do with Flynn international FISA warrants from years before he was even targeted under Trump. Flynn was under surveillance ever since he leftleft thethe DIADIA inin 21042104 andand TrumpTrump waswas notnot eveneven runningrunning forfor officeoffice atat thethe time.time. So Flynn was not a Trump associate target at that time. Nor had any Russia collusion narrative been concocted by the Obama team yet either. That happened only in 2016. Manafort had been spied on since 2014 also, as noted in the video below. This link explains when Flynn left the DIA: https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/04/30/defense-intelligence-agencys- flynn-leaving-after-rocky-tenure/ ► Flynn took on his job in 2012, clearly during the Obama time. What “Q” claims about Flynn thus is non-applicable. This because there were no FISA warrants on Flynn or Manafort at the time Trump decided to run for office and when Cross-Fire Hurricane initiated in the Obama – Susan Rice 2016 meeting as an attempt to pin a DNC hack on the Russians in order to cover-up the murder of Seth Rich. -

False Beliefs: Byproducts of an Adaptive Knowledge Base? 131 Elizabeth J

“This volume provides a great entry point into the vast and growing psycho- logical literature on one of the defining problems of the early 21st century – fake news and its dissemination. The chapters by leading scientists first focus on how (false) information spreads online and then examine the cognitive processes involved in accepting and sharing (false) information. The volume concludes by reviewing some of the available countermeasures. Anyone new to this area will find much here to satisfy their curiosity.” – Stephan Lewandowsky , Cognitive Science, University of Bristol, UK “Fake news is a serious problem for politics, for science, for journalism, for con- sumers, and, really, for all of us. We now live in a world where fact and fiction are intentionally blurred by people who hope to deceive us. In this tremendous collection, four scientists have gathered together some of the finest minds to help us understand the problem, and to guide our thinking about what can be done about it. The Psychology of Fake News is an important and inspirational contribu- tion to one of society’s most vexing problem.” – Elizabeth F Loftus , Distinguished Professor, University of California, Irvine, USA “This is an interesting, innovative and important book on a very significant social issue. Fake news has been the focus of intense public debate in recent years, but a proper scientific analysis of this phenomenon has been sorely lacking. Con- tributors to this excellent volume are world-class researchers who offer a detailed analysis of the psychological processes involved in the production, dissemina- tion, interpretation, sharing, and acceptance of fake news. -

Rich Vs Butowsky – Thomas Schoenberger Deposition 627 2019

Page 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA AARON RICH, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) vs. )Case No. Civil Action ) 1:18-cv-00681-RJL EDWARD BUTOWSKY, ) MATTHEW COUCH, and ) AMERICA FIRST MEDIA, ) ) Defendants. ) _____________________________ ) Videotaped Deposition of THOMAS ANDREW SCHOENBERGER, taken on behalf of Plaintiff, at 725 South Figueroa Street, 31st Floor, Los Angeles, California 90017, beginning at 10:18 a.m., and ending at 5:40 p.m., on Thursday, June 27, 2019, before Marceline F. Noble, RPR, CRR, Certified Shorthand Reporter No. 3024. Magna Legal Services 866-624-6221 www.MagnaLS.com Reported by: Marceline F. Noble, CSR No. 3024 Job No. 489984 Page 2 1 APPEARANCES: 2 For Plaintiff: 3 BOIES SCHILLER FLEXNER LLP BY: JOSHUA P. RILEY, ESQ. 4 AND CHLOE M. HOUDRE, ESQ. 1401 New York Avenue NW 5 Washington, D.C. 20005 212.237.2727 6 [email protected] [email protected] 7 8 For Defendants: 9 (No appearance) 10 11 12 Also Present: 13 RYAN MURPHY, Videographer Magna Video Services 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Page 3 1 INDEX 2 WITNESS EXAMINATION 3 THOMAS ANDREW SCHOENBERGER 4 By Mr. Riley 6 5 By Ms. Houdre 256 6 7 8 EXHIBITS 9 EXHIBIT DESCRIPTION PAGE 10 A Plaintiff Aaron Rich's Notice of 11 11 Intent to Serve Third-Party Subpoena 12 B Email, 6/5/19, to E. Butowsky from 13 13 Hall, Samuel 14 C "SHADOWBOX CORPORATE" 27 15 D "Shadowbox" 35 16 E Email, 6/20/19, to Hall, Samuel 80 from Revolution Fox 17 F Email, 8/10/17, to Defango from 90 18 CoyoteRio 19 G Email, 3/3/18, to E. -

Donna Brazile Feared for Her Life After the Murder of Seth Rich, the Suspected DNC Leaker

Donna Brazile Feared for Her Life After the Murder of Seth Rich, the Suspected DNC Leaker Former head of the DNC, Donna Brazile, wrote in her new book that she feared for her life after the murder of suspected DNC leaker Seth Rich. Her fear that Rich’s death was a political hit contradicts the official story that his murder was a botched robbery. Private detective, Rod Wheeler, who was hired on behalf of the Rich family to investigate their son’s death, says that Brazile called him and accused him of “snooping” and demanded to know why the investigation was still going on after he visited the police station and asked some questions earlier this year. GEG Newly released excerpts from Donna Brazile’s book “Hacks: The Inside Story of the Break-ins and Breakdowns That Put Donald Trump in the White House,” reveals the Democrat operative was haunted by the mysterious death of DNC staffer Seth Rich. Drudge says Brazile was so paranoid about snipers shooting her dead that she made a habit of shutting the blinds. “Brazile writes she was haunted by murder of DNC Seth Rich, and feared for her own life, shutting the blinds so snipers could not see her,” tweeted Drudge on Saturday afternoon. “Brazile writes that she was haunted by the still-unsolved murder of DNC data staffer Seth Rich and feared for her own life, shutting the blinds to her office window so snipers could not see her and installing surveillance cameras at her home,” writes Philip Rucker of the Washington Post. -

![Towards Understanding the Information Ecosystem Through the Lens of Multiple Web Communities Arxiv:1911.10517V1 [Cs.SI] 24](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0426/towards-understanding-the-information-ecosystem-through-the-lens-of-multiple-web-communities-arxiv-1911-10517v1-cs-si-24-5150426.webp)

Towards Understanding the Information Ecosystem Through the Lens of Multiple Web Communities Arxiv:1911.10517V1 [Cs.SI] 24

Towards Understanding the Information Ecosystem Through the Lens of Multiple Web Communities Savvas Zannettou A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Cyprus University of Technology. arXiv:1911.10517v1 [cs.SI] 24 Nov 2019 Department of Electrical Engineering, Computer Engineering and Informatics Cyprus University of Technology November 26, 2019 Abstract The Web consists of numerous Web communities, news sources, and services, which are often ex- ploited by various entities for the dissemination of false or otherwise malevolent information. Yet, we lack tools and techniques to effectively track the propagation of information across the multiple diverse communities, and to capture and model the interplay and influence between them. Further- more, we lack a basic understanding of what the role and impact of some emerging communities and services on the Web information ecosystem are, and how such communities are exploited by bad actors (e.g., state-sponsored trolls) that spread false and weaponized information. In this thesis, we shed some light on the complexity and diversity of the information ecosystem on the Web by presenting a typology that includes the various types of false information, the involved actors as well as their possible motives. Then, we follow a data-driven cross-platform quantitative approach to analyze billions of posts from Twitter, Reddit, 4chan’s Politically Incorrect board (/pol/), and Gab, to shed light on: 1) how news and image-based memes travel from one Web community to another and how we can model and quantify the influence between the various Web communities; 2) characterizing the role of emerging Web communities and services on the information ecosystem, by studying Gab and two popular Web archiving services, namely the Wayback Machine and archive.is; and 3) how popular Web communities are exploited by state-sponsored actors for the purpose of spreading disinformation and sowing public discord. -

U.S. War Criminals, Conspiracy Theorists and the Mainstream Media Vs. Julian Assange

U.S. War Criminals, Conspiracy Theorists and the Mainstream Media vs. Julian Assange By Timothy Alexander Guzman Region: USA Global Research, May 27, 2019 Theme: Law and Justice, Media Disinformation Julian Assange exposed U.S. war crimes, CIA spying capabilities, false flag cyber attacks and corruption within the Democratic Party and he’s the bad guy? Trump’s Justice department has decided to charge Julian Assange with “17 counts of violating the Espionage Act for his role in obtaining and publishing secret military and diplomatic documents in 2010, the Justice Department announced on Thursday, a novel case that raises profound First Amendment issues” according to The New York Times. The article ‘Assange Indicted Under Espionage Act, Raising First Amendment Issues’ does mention the fact that charging Assange under the Espionage Act sets the precedent to criminalize investigative journalism that is “related to obtaining, and in some cases publishing, state secrets to be criminal, the officials sought to minimize the implications for press freedoms.” However, The New York Times has become the judge and jury and says that Assange is a fugitive trying to avoid Sweden’s justice system for an alleged sexual assault charge and that he is a useful tool for the Russians in regards to interfering in U.S. elections: The charges are the latest twist in a career in which Mr. Assange has morphed from a crusader for radical transparency to fugitive from a Swedish sexual assault investigation, to tool of Russia’s election interference, to criminal defendant in the United States. Mr. Assange vaulted to global fame nearly a decade ago as a champion of openness about what governments secretly do.