WA303 20374 1965-12 APH 08 O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polish Research on the Life and Wide-Ranging Activity of Nicholas Copernicus **

The Global and the Local: The History of Science and the Cultural Integration of Europe. nd Proceedings of the 2 ICESHS (Cracow, Poland, September 6–9, 2006) / Ed. by M. Kokowski. Marian Biskup * Polish research on the life and wide-ranging activity of Nicholas Copernicus ** FOR MANY YEARS NOW ATTENTION has been paid in the Polish science to the need to show the whole of life and activity of Nicholas Copernicus. It leads to the better understanding of his scientific workshop and the conditions he worked in. Therefore, first a detailed index of all the source documents was published in 1973, in Regesta Copernicana, in both Polish and English version. It included 520 the then known source documents, from the years 1448–1550, both printed as well as sourced from the Swedish, Italian, German and Polish archives and libraries.1 This publication allowed to show the full life of Copernicus and his wide interests and activities. It also made it possible to show his attitude towards the issues of public life in Royal Prussia — since 1454 an autonomous part of the Polish Kingdom — and in bishop’s Warmia, after releasing from the rule of the Teutonic Order. Nicholas Copernicus lived in Royal Prussia since his birth in 1473 and — excluding a few years devoted to studies abroad — he spent his entire life there, until his death in 1543. He was born in Toruń, a bilingual city (German and Polish) which, since 1454, was under the rule of the Polish king. There he adopted the lifestyle and customs of rich bourgeoisie, as well as its mentality, also the political one. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The science of the stars in Danzig from Rheticus to Hevelius / Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7n41x7fd Author Jensen, Derek Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO THE SCIENCE OF THE STARS IN DANZIG FROM RHETICUS TO HEVELIUS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History (Science Studies) by Derek Jensen Committee in charge: Professor Robert S. Westman, Chair Professor Luce Giard Professor John Marino Professor Naomi Oreskes Professor Donald Rutherford 2006 The dissertation of Derek Jensen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii FOR SARA iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page........................................................................................................... iii Dedication ................................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents ...................................................................................................... v List of Figures .......................................................................................................... -

Nicolaus Copernicus Immanuel Kant

NICOLAUS COPERNICUS IMMANUEL KANT The book was published as part of the project: “Tourism beyond the boundaries – tourism routes of the cross-border regions of Russia and North-East Poland” in the part of the activity concerning the publishing of the book “On the Trail of Outstanding Historic Personages. Nicolaus Copernicus – Immanuel Kant” 2 Jerzy Sikorski • Janusz Jasiński ON THE TRAIL OF OUTSTANDING HISTORIC PERSONAGES NICOLAUS COPERNICUS IMMANUEL KANT TWO OF THE GREATEST FIGURES OF SCIENCE ON ONCE PRUSSIAN LANDS “ElSet” Publishing Studio, Olsztyn 2020 PREFACE The area of former Prussian lands, covering the southern coastal strip of the Baltic between the lower Vistula and the lower Nemunas is an extremely complicated region full of turmoil and historical twists. The beginning of its history goes back to the times when Prussian tribes belonging to the Balts lived here. Attempts to Christianize and colonize these lands, and finally their conquest by the Teutonic Order are a clear beginning of their historical fate and changing In 1525, when the Great Master relations between the Kingdom of Poland, the State of the Teutonic Order and of the Teutonic Order, Albrecht Lithuania. The influence of the Polish Crown, Royal Prussia and Warmia on the Hohenzollern, paid homage to the one hand, and on the other hand, further state transformations beginning with Polish King, Sigismund I the Old, former Teutonic state became a Polish the Teutonic Order, through Royal Prussia, dependent and independent from fief and was named Ducal Prussia. the Commonwealth, until the times of East Prussia of the mid 20th century – is The borders of the Polish Crown since the times of theTeutonic state were a melting pot of events, wars and social transformations, as well as economic only changed as a result of subsequent and cultural changes, whose continuity was interrupted as a result of decisions partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793, madeafter the end of World War II. -

Narratio Prima Or First Account of the Books on the Revolution By

Foreword It is with great pleasure that we can present a facsimile edition of the Narratio Prima by Georg Joachim Rheticus. This book, an abstract and resumé of Nicolaus Copernicus’ De Revoltionibus, was written when both these schol- ars were staying at Lubawa Castle in the summer of 1539. Their host was a friend of Copernicus, Tiedemann Giese, the Bishop of Culm. Published three years before the work of Copernicus, the Narratio Prima recounts, in a clear and concise manner, the heliocentric theory of the great Polish scholar. We have also prepared the first-ever translation of Rheticus’ book for Polish readers, published in its own separate volume. Several years ago, I had an interesting discussion with Professor Jarosław 5 Włodarczyk from the Institute for the History of Science at the Polish Academy of Sciences about the significance of the time Nicolaus Copernicus spent in the land of Lubawa. It is this charming land, shaped by a melting glacier, that the Nicolaus Copernicus Foundation, whose works I am hon- oured to oversee, has chosen for its seat. It is also here that the Nicolaus Copernicus Foundation has constructed its two astronomical observatories, in Truszczyny and Kurzętnik. It was at Lubawa Castle that Nicolaus Copernicus, persuaded by his friends Giese and Rheticus, decided to publish his work. This canonical book was later to become one of the milestones of modern science. Moreover, it Narratio prima or First Account of the Books “On the Revolutions”… is in Lubawa that Rheticus, amazed by the groundbreaking theory exposed by his teacher in De Revolutionibus, wrote his own book. -

K. Friedrich: the Other Prussia

K. Friedrich: The Other Prussia Friedrich, Karin: The other Prussia. Royal Friedrich rightly believes have been overly in- Prussia, Poland and liberty, 1569-1772. Cam- fluenced by nineteenth and twentieth-century bridge: Cambridge University Press 2000. national prejudice. The book opens with ISBN: 0-521-58335-7; XXI + 280 S. a sustained attack on the ’Germanisation’ of Prussian history which echoes and ex- Rezensiert von: Gudrun Gersmann, Institut tends the author’s earlier condemnation of für Neuere Geschichte, LMU München this trend in her recent contributions (’fac- ing both ways: new works on Prussia and The rise of the German Machtstaat and the Polish-Prussian relations’, in: German His- demise and subsequent re-emergence of a Pol- tory 15 [1997], 256-267, and ’Politisches Lan- ish national state have cast a long shadow desbewußtsein und seine Trägerschichten im over Prussian history. In her impressive first Königlichen Preußen’, in: Nordost-Archiv NS book, Karin Friedrich seeks to expose the na- 6, [1997], 541-564). In discussing the Prus- tionalist distortions of past historical writ- sification of German history entailed by the ing and, in particular, rescue the ’other Prus- Borussian myth of Hohenzollern Prussia’s sia’ from the relative obscurity imposed by destiny to unite the German lands, she rightly its long incorporation in the Hohenzollern identifies the Germanisation of Prussian his- monarchy 1772-1918. At the heart of this en- tory which drew a ’direct line’ from the Teu- deavour is the attempt to recover and explain tonic Knights to the Hohenzollern dynasty. the formation of Royal (or Polish) Prussian Continued by the subsequent tradition of Os- identity, primarily from the perspective of the tforschung, this interpretation constructed a burghers of the province’s three great cities: false ’Prussian identity’, supposedly based on Danzig, Thorn and Elbing. -

![6 Stefan Kwiatkowski [648] in the Scope of Military Preparations, the Situation Was Changing Dynami- Cally, Especially Between 1453–1454](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1023/6-stefan-kwiatkowski-648-in-the-scope-of-military-preparations-the-situation-was-changing-dynami-cally-especially-between-1453-1454-1871023.webp)

6 Stefan Kwiatkowski [648] in the Scope of Military Preparations, the Situation Was Changing Dynami- Cally, Especially Between 1453–1454

ZAPISKI HISTORYCZNE — TOM LXXXI — ROK 2016 Zeszyt 4 http://dx.doi.org./10.15762/ZH.2016.46 STEFAN KWIATKOWSKI (University of Szczecin) A CONFLICT FOR VALUES IN THE ORIGINS AND AT THE BEGINNING OF THE THIRTEEN YEARS’ WAR Key words: the Teutonic Order, Prussian Confederation, law and justice in cultural sense The aim of the paper is to picture the issue of understanding the question of war and peace on the eve and at the beginning of the unpredictable in its consequences conflict. Obviously, the starting points are the parties present in Prussia, that is the Teutonic Order on the one hand, and, on the other, its con- federated subjects. The Polish Kingdom and other external factors engaged the war with their own program, having little in common with the country’s interest. Not only did the Teutonic Order and Prussian Estates understand war and peace in practical terms, but also perceived it through the prism of re- ligion, morality, scholastic thought, and jurisprudence. Both parties had been engaging in a political struggle for decades, during which both of the sides reached for arguments borrowed from broadly defined Christian doctrine. In the middle of 15th century, they acquired a local color which ignited a deep ir- ritation among the order brothers who came from the Reich. Two conflicting ideas for the country order were opposed: the Order’s and the Estate’s views. They had been clashing for a longer time, and finally became irreconcilable. The order, when it comes to principle, stood on the grounds of the Divine Law, which was unalterable and eternal. -

August Hermann Francke, Friedrich Wilhelm I, and the Consolidation of Prussian Absolutism

GOD'S SPECIAL WAY: AUGUST HERMANN FRANCKE, FRIEDRICH WILHELM I, AND THE CONSOLIDATION OF PRUSSIAN ABSOLUTISM. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Terry Dale Thompson, B.S., M.A., M.T.S. * ★ * * * The Ohio State University 1996 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor James M. Kittelson, Adviser Professor John F. Guilmartin ^ / i f Professor John C. Rule , J Adviser Department of History UMI Number: 9639358 Copyright 1996 by Thompson, Terry Dale All rights reserved. UMI Microform 9639358 Copyright 1996, by UMI Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. UMI 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 COPYRIGHT BY TERRY DALE THOMPSON 1996 ABSTRACT God's Special Way examines the relationship between Halle Pietism and the Hohenzollern monarchy in order to discern the nature and effect on Brandenburg-Prussia of that alliance. Halle Pietism was a reform movement within the Lutheran church in 17th and 18th century Germany that believed the establishment church had become too concerned with correct theology, thus they aimed at a revival of intense Biblicism, personal spirituality, and social reform. The Pietists, led by August Hermann Francke (1662-1727) , and King Friedrich Wilhelm I (rl7l3-l740) were partners in an attempt to create a Godly realm in economically strapped and politically divided Brandenburg-Prussia. In large measure the partnership produced Pietist control of Brandenburg- Prussia'a pulpits and schoolrooms, despite the opposition of another informal alliance, this between the landed nobility and the establishment Lutheran church, who hoped to maintain their own authority in the religious and political spheres. -

The Nicolaus Copernicus Grave Mystery. a Dialog of Experts

POLISH ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES The Nicolaus Copernicus On 22–23 February 2010 a scientific conference “The Nicolaus Copernicus grave mystery. A dialogue of experts” was held in Kraków. grave mystery The institutional organizers of the conference were: the European Society for the History of Science, the Copernicus Center for Interdisciplinary Studies, the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences with its two commissions (the Commission on the History of Science, and the Commission on the Philosophy of Natural Sciences), A dialogue of experts the Institute for the History of Science of the Polish Academy of Sciences, and the Tischner European University. Edited by Michał Kokowski The purpose of this conference was to discuss the controversy surrounding the discovery of the grave of Nicolaus Copernicus and the identification of his remains. For this reason, all the major participants of the search for the grave of Nicolaus Copernicus and critics of these studies were invited to participate in the conference. It was the first, and so far only such meeting when it was poss- ible to speak openly and on equal terms for both the supporters and the critics of the thesis that the grave of the great astronomer had been found and the identification of the found fragments of his skeleton had been completed. [...] In this book, we present the aftermath of the conference – full texts or summa- ries of them, sent by the authors. In the latter case, where possible, additional TERRA information is included on other texts published by the author(s) on the same subject. The texts of articles presented in this monograph were subjected to sev- MERCURIUS eral stages of review process, both explicit and implicit. -

High Clergy and Printers: Antireformation Polemic in The

bs_bs_banner High clergy and printers: anti-Reformation polemic in the kingdom of Poland, 1520–36 Natalia Nowakowska University of Oxford Abstract Scholarship on anti-Reformation printed polemic has long neglected east-central Europe.This article considers the corpus of early anti-Reformation works produced in the Polish monarchy (1517–36), a kingdom with its own vocal pro-Luther communities, and with reformed states on its borders. It places these works in their European context and, using Jagiellonian Poland as a case study, traces the evolution of local polemic, stresses the multiple functions of these texts, and argues that they represent a transitional moment in the Polish church’s longstanding relationship with the local printed book market. Since the nineteen-seventies, a sizeable literature has accumulated on anti-Reformation printing – on the small army of men, largely clerics, who from c.1518 picked up their pens to write against Martin Luther and his followers, and whose literary endeavours passed through the printing presses of sixteenth-century Europe. In its early stages, much of this scholarship set itself the task of simply mapping out or quantifying the old church’s anti-heretical printing activity. Pierre Deyon (1981) and David Birch (1983), for example, surveyed the rich variety of anti-Reformation polemical materials published during the French Wars of Religion and in Henry VIII’s England respectively.1 John Dolan offered a panoramic sketch of international anti-Lutheran writing in an important essay published in 1980, while Wilbirgis Klaiber’s landmark 1978 database identified 3,456 works by ‘Catholic controversialists’ printed across Europe before 1600.2 This body of work triggered a long-running debate about how we should best characterize the level of anti-Reformation printing in the sixteenth century. -

The Church in Royal and Teutonic Prussia After the Second Peace of Toruń: the Time of Continuation and Change

ZAPISKI HISTORYCZNE — TOM LXXXI — ROK 2016 Zeszyt 4 http://dx.doi.org./10.15762/ZH.2016.49 ANDRZEJ RADZIMIŃSKI (Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń) THE CHURCH IN ROYAL AND TEUTONIC PRUSSIA AFTER THE SECOND PEACE OF TORUŃ: THE TIME OF CONTINUATION AND CHANGE Key words: dioceses of Chełmno, Pomesania, Sambia, Ermland [Warmia], territo- rial dominion of Prussian bishops, cathedral chapters, Pomeranian arch deaconry, parishes In this paper I shall discuss direct and indirect consequences of the Sec- ond Peace of Toruń referring to the situation of the Church in the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights in Prussia until the Reformation period. I shall present the elements of continuation and change, which resulted both from the new political system of the subordination of dioceses and from the gradu- ally changing legal position of individual bishoprics and their superiors1. The decisions of the Second Peace of Toruń of 19 October 1466 brought about not only the significant political-territorial changes in the relations be- tween Poland and the Teutonic Order, but also led to serious territorial-judi- cial alterations in the church structures situated earlier on the territory of the Monastic State2. After 1466 there also took place a gradual change in the legal 1 The syntheses of the history of the Teutonic Order published so far lack a deeper reflec- tion concerning the situation of the Church in Prussia after the Second Treaty of Toruń. See for example: Hartmut Boockmann, Zakon Krzyżacki. Dwanaście rozdziałów jego historii, Warsza- wa 1998, pp. 231–257; Marian Biskup, Gerard Labuda, Dzieje zakonu krzyżackiego w Prusach, Gdańsk 1986, pp. -

Bulletin 26Iii Sonderegger

UNEXPECTED ASPECTS OF ANNIVERSARIES or: Early sundials, widely travelled HELMUT SONDEREGGER his year my hometown, Feldkirch in Germany, cel- Iserin was appointed town physician and all of his family ebrates the 500th anniversary of Rheticus. He was were accepted as citizens of Feldkirch. Georg, a man with T the man who published the first report on Coperni- widespread interests, owned a considerable number of cus’s new heliocentric view of the world. Subsequently, he books and a collection of alchemical and medical instru- helped Copernicus complete his manuscript for publication ments. Over the years, superstitious people suspected this and arranged its printing in Nürnberg. When I planned my extraordinary man of being a sorcerer in league with attendance at the BSS Conference 2014 at Greenwich, I sources of darkness. asked myself if there could be any connections between the A few weeks before his appointment as town physician, on th th 25 BSS anniversary and the 500 anniversary of Rheticus’ 16 Feb 1514, his only son Georg Joachim was born. When birth. And now in fact, I have found a really interesting the son was 14 his father was accused of betraying his story! patients and, additionally, of being a swindler and klepto- maniac. He was sentenced to death and subsequently Feldkirch 500 Years Ago beheaded by the sword. His name Iserin was officially Feldkirch, a small district capital of about 30,000 people, is erased by so-called ‘damnatio memoriae’. His wife and situated in the very west of Austria close to Switzerland children changed their name to the mother’s surname. -

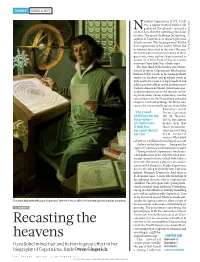

Recasting the Heavens

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS icolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) was a quintessential unifier. He gathered the planets around a Ncentral Sun, thereby inventing the Solar System. The grand challenge facing biog- raphers of Copernicus is that few personal details survive. Was he gregarious? Did he have a girlfriend in his youth? When did he become interested in the stars? Because the historical record answers none of these questions, some authors have resorted to STOCK GEOGRAPHIC J.-L. HUENS/NATIONAL fiction. In A More Perfect Heaven, science historian Dava Sobel has it both ways. The first third of the book is strictly his- torical. It traces Copernicus’s life from his birth in Polish Toruń, to his undergraduate studies in Kraków and graduate work in Italy, and to his career as a legal, medical and administrative officer in the northernmost Catholic diocese of Poland. Sobel makes par- ticularly effective use of the records surviv- ing from when Canon Copernicus was the rent collector for the Frauenburg cathedral chapter’s vast land holdings. To fill the nar- rative, she occasionally quotes from John Banville’s novel “The grand Doctor Copernicus challenge facing (W. W. Norton, biographers 1976), but always of Copernicus makes clear that is that few those reconstruc- personal details tions are not taken survive.” from archival sources. What Sobel achieves is a brilliant chronological account — the best in the literature — laying out the stages of Copernicus’s administrative career. Having reached Copernicus’s final years, when publication of his still unfinished man- uscript seemed to have stalled, Sobel takes a new tack.