An Issue for Urban Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

111318-19 Bk Jschmidt EU 10/15/07 2:47 PM Page 8

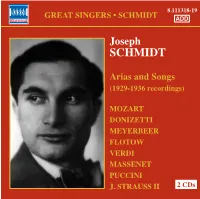

111318-19 bk JSchmidt EU 10/15/07 2:47 PM Page 8 8.111318-19 CD 1: CD 2: GREAT SINGERS • SCHMIDT Tracks 1, 2, 5 and 9: Tracks 1, 5 and 16: ADD Berlin State Opera Orchestra • Selmar Meyrowitz Orchestra • Felix Günther Tracks 3 and 4: Tracks 2, 6-9, 20-23: Vienna Parlophon Orchestra • Felix Günther Berlin State Opera Orchestra Selmar Meyrowitz Joseph Track 6: Berlin State Opera Orchestra • Clemens Schmalstich Tracks 3, 4, and 13: Berlin State Opera Orchestra SCHMIDT Tracks 7 and 8: Frieder Weissmann Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra • Selmar Meyrowitz Tracks 10-12, 14, 15, 18, and 19: Track 10: Orchestra • Otto Dobrindt With Max Saal, harp Arias and Songs Track 17: Track 11: Orchestra • Clemens Schmalstich Orchestra and Chorus • Clemens Schmalstich (1929-1936 recordings) Tracks 12 and 13: Languages: Berlin Symphony Orchestra • Frieder Weissmann CD 1: MOZART Tracks 14, 15, 17, 18 and 24: Tracks 1, 3-6, 9-13, 16-18, 21-24 sung in German Orchestra of the Staatsoper Berlin Tracks 2, 7, 8, 14, 15, 19, 20 sung in Italian Frieder Weissmann DONIZETTI CD 2: Track 16: Tracks 1-16 sung in German MEYERBEER Orchestra • Leo Blech Track 17 sung in Spanish Tracks 18-23 sung in Italian Tracks 19 and 20: FLOTOW Orchestra • Walter Goehr Tracks 21-23: VERDI Orchestra • Otto Dobrindt MASSENET PUCCINI J. STRAUSS II 2 CDs 8.111318-19 8 111318-19 bk JSchmidt EU 10/15/07 2:47 PM Page 2 Joseph Schmidt (1904-1942) LEHAR: Das Land des Lächelns: MAY: Ein Lied geht um die Welt: 8 Von Apfelblüten eine Kranz (Act I) 3:43 ^ Wenn du jung bist, gehört dir die Welt 3:09 Arias and Songs (1929-1936 recordings) Recorded on 24th October 1929; Recorded in January 1934; Joseph Schmidt’s short-lived career was like that of a 1924 he decided to take the plunge into a secular Mat. -

Stanislaw Brzozowski and the Migration of Ideas

Jens Herlth, Edward M. Świderski (eds.) Stanisław Brzozowski and the Migration of Ideas Lettre Jens Herlth, Edward M. Świderski (eds.) with assistance by Dorota Kozicka Stanisław Brzozowski and the Migration of Ideas Transnational Perspectives on the Intellectual Field in Twentieth-Century Poland and Beyond This volume is one of the outcomes of the research project »Standing in the Light of His Thought: Stanisław Brzozowski and Polish Intellectual Life in the 20th and 21st Centuries« funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (project no. 146687). The publication of this book was made possible thanks to the generous support of the »Institut Littéraire Kultura«. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for com- mercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting [email protected] Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. -

The Hungarian Historical Review Nationalism & Discourses

The Hungarian Historical Review New Series of Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Volume 5 No. 2 2016 Nationalism & Discourses of Objectivity: The Humanities in Central Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century Bálint Varga Special Editor of the Thematic Issue Contents Articles GÁBOR ALMÁSI Faking the National Spirit: Spurious Historical Documents in the Service of the Hungarian National Movement in the Early Nineteenth Century 225 MILOŠ ŘEZNÍK The Institutionalization of the Historical Science betwixt Identity Politics and the New Orientation of Academic Studies: Wácslaw Wladiwoj Tomek and the Introduction of History Seminars in Austria 250 ÁDÁM BOLLÓK Excavating Early Medieval Material Culture and Writing History in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Hungarian Archaeology 277 FILIP TOMIĆ The Institutionalization of Expert Systems in the Kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia: The Founding of the University of Zagreb as the Keystone of Historiographic Professionalization, 1867–1918 305 MICHAEL ANTOLOVIĆ Modern Serbian Historiography between Nation-Building and Critical Scholarship: The Case of Ilarion Ruvarac (1832–1905) 332 ALEKSANDAR PAVLOVIĆ From Myth to Territory: AND Vuk Karadžić, Kosovo Epics and the Role SRĐAN ATANASOVSKI of Nineteenth-Century Intellectuals in Establishing National Narratives 357 http://www.hunghist.org HHHR_2016-2.indbHR_2016-2.indb 1 22016.07.29.016.07.29. 112:50:102:50:10 Contents Featured Review The Past as History: National Identity and Historical Consciousness in Modern Europe. By Stefan Berger, with Christoph Conrad. (Writing the Nation series) Reviewed by Gábor Gyáni 377 Book Reviews Zsigmond király Sienában [King Sigismund in Siena]. By Péter E. Kovács. Reviewed by Emőke Rita Szilágyi 384 Imprinting Identities: Illustrated Latin-Language Histories of St. -

9914396.PDF (12.18Mb)

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fece, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Ifigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnaticn Compare 300 North Zeeb Road, Aim Arbor NO 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with indistinct print. Pages were microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available UMI THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO THREE SACRED CHORAL/ ORCHESTRAL WORKS BY ANTONIO CALDARA: Magnificat in C. -

Franz Schubert: Inside, out (Mus 7903)

FRANZ SCHUBERT: INSIDE, OUT (MUS 7903) LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF MUSIC & DRAMATIC ARTS FALL 2017 instructor Dr. Blake Howe ([email protected]) M&DA 274 meetings Thursdays, 2:00–4:50 M&DA 273 office hours Fridays, 9:30–10:30 prerequisite Students must have passed either the Music History Diagnostic Exam or MUS 3710. Blake Howe / Franz Schubert – Syllabus / 2 GENERAL INFORMATION COURSE DESCRIPTION This course surveys the life, works, and times of Franz Schubert (1797–1828), one of the most important composers of the nineteenth century. We begin by attempting to understand Schubert’s character and temperament, his life in a politically turbulent city, the social and cultural institutions that sponsored his musical career, and the circles of friends who supported and inspired his artistic vision. We turn to his compositions: the influence of predecessors and contemporaries (idols and rivals) on his early works, his revolutionary approach to poetry and song, the cultivation of expression and subjectivity in his instrumental works, and his audacious harmonic and formal practices. And we conclude with a consideration of Schubert’s legacy: the ever-changing nature of his posthumous reception, his impact on subsequent composers, and the ways in which modern composers have sought to retool, revise, and refinish his music. COURSE MATERIALS Reading assignments will be posted on Moodle or held on reserve in the music library. Listening assignments will link to Naxos Music Library, available through the music library and remotely accessible to any LSU student. There is no required textbook for the course. However, the following texts are recommended for reference purposes: Otto E. -

Josef Schmidt

baritone, then director of Berlin Radio. His Memories of international reputation was made on 29 March 1929 when he sang the pocket Caruso role of Vasco de Gama in Meyerbeer's by Harry Jarvis L'Africaine and fan MiL TTENDING a music appreciation class of the mail poured in from ^J^ University of the Third Age (USA) gave me a chance wherever the broadcast F Mto listen to a CD entitled Ein Lied geht um die Welt had been relayed. by Josef Schmidt.' As an assiduous collector of genealogical Recordings were material since the age of 17, I have had various articles made by Ultraphon published in Shemot on my home town of Czernowitz (Telefunken) and HMV Josef Schmidt (Chernovtsy), the principal Yiddish-speaking centre of and issued that year. 1904-1942 Bukovina, a territory now in Ukraine, which had over the Subsequently he years been subject to numerous occupations and was then recorded largely for Odeon/Parlophone. part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.2 It is ironical to note that his popularity among German- Now in my 80s, with my memory for recent events speaking countries was at its height in 1933 just when the somewhat dimmed, I have a clear recollection of being taken Nazi party was taking power. Between 1933 and 1936, he as a child to the beautiful large temple in the town centre to made an English version of the film Ein Lied geht um die hear the then well-known film star and international opera singer Welt (My song goes round the world) as well as Wenn du Josef Schmidt who invariably returned to his home town each Jung bist, Ein Stem fallt von Himmel (A star falls from year to act as cantor during the high holidays. -

Joseph Schmidt (1904-2004)

Joseph Schmidt (1904-2004) Jan Neckers 21 September 2004 This is not a biography of the Jewish tenor. Just some personal thoughts on a few interesting aspects. Those interested in a biographical article and an outstanding discography better purchase the June 2000 issue of The Record Collector where your servant and Hansfried Sieben devoted more than sixty small print pages to the tenor. Those able to read German can still buy Alfred Fasbind’s biography published at the Schweizer Verlagshaus in Zurich¨ 1992. It is still available in some German bookshops and maybe with the author himself (Rosenbergstrasse 16, 8630 Ruti,¨ Switzerland). So, what can I tell you that’s not in the article? Well, it is a pity Schmidt was not a Brit or an American or even a Frenchman. Nobody reading his biography can fail to muse on the many ordeals he lived through in his short life. (though of course he was not alone in this as millions of those unlucky generations born in Europe around 1900 would share his fate). And nobody reading it can fail to recognize an outstanding script for a magnificent movie or an outstanding series in the best Forsythe-tradition. Yes, the Germans produced a movie in 1958 which used the tenor’s singing voice but it belongs in the category ‘ought to be seen to be believed’. The makers succeeded in eliminating Schmidt’s personal tragedy completely as the actor playing the tenor measured at least some 35 centimetres more than the very small singer. (Forget the usual measure given of 1.55 m which is still 5 feet. -

Copyright by Agnieszka Barbara Nance 2004

Copyright by Agnieszka Barbara Nance 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Agnieszka Barbara Nance Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Nation without a State: Imagining Poland in the Nineteenth Century Committee: Katherine Arens, Supervisor Janet Swaffar Kirsten Belgum John Hoberman Craig Cravens Nation without a State: Imagining Poland in the Nineteenth Century by Agnieszka Barbara Nance, B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2004 Nation without a State: Imagining Poland in the Nineteenth Century Publication No._____________ Agnieszka Barbara Nance, PhD. The University of Texas at Austin, 2004 Supervisor: Katherine Arens This dissertation tests Benedict Anderson’s thesis about the coherence of imagined communities by tracing how Galicia, as the heart of a Polish culture in the nineteenth century that would never be an independent nation state, emerged as an historical, cultural touchstone with present day significance for the people of Europe. After the three Partitions and Poland’s complete disappearance from political maps of Europe, substitute images of Poland were sought that could replace its lost kingdom with alternate forms of national identity grounded in culture and tradition rather than in politics. Not the hereditary dynasty, not Prussia or Russia, but Galicia emerged as the imagined and representative center of a Polish culture without a state. This dissertation juxtaposes political realities with canonical literary texts that provide images of a cultural community among ethnic Germans and Poles sharing the border of Europe. -

Where Words Leave Off, Music Begins”

CG1009 Degree Project, Bachelor, Classical Music, 15 credits 2017 Degree of Bachelor in Music Department of Classical Music Supervisor: David Thyrén Examiner: Peter Berlind Carlson Philip Sherman ”Where words leave off, music begins” A comparison of how Henry Purcell and Franz Schubert convey text through their music in the compositions Music for a while and Erlkönig Skriftlig reflektion inom självständigt, konstnärligt arbete Inspelning av det självständiga, konstnärliga arbetet finns dokumenterat i det tryckta exemplaret av denna text på KMH:s bibliotek. Summary ”The singer is always working through a text that in some way or another inspired the vocal line and its texture,” wrote American pianist, pedagogue, and author Thomas Grubb. But exactly how does a text inspire a composer to create this synergy between words and music? During the course of my studies at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm, I gradually began to deepen my knowledge and awareness of Henry Purcell and Franz Schubert. I was at once astounded by their ability to seemlessly amalgamate the chosen texts to their music, and decided that this connection required greater research. The purpose of this study was thus to gain a deeper understanding of how Purcell and Schubert approached the relationship between text and music by studying the two pieces Music for a while and Erlkönig. I also wished to discover any similarities and differences between the composers’ approaches to word painting, in addition to discerning the role of the accompaniment to further illustrate the narrative. I began by reading literature about the two composers as well as John Dryden and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the poets whose texts were set to music. -

NEE 2015 2 FINAL.Pdf

ADVERTISEMENT NEW EASTERN EUROPE IS A COLLABORATIVE PROJECT BETWEEN THREE POLISH PARTNERS The City of Gdańsk www.gdansk.pl A city with over a thousand years of history, Gdańsk has been a melting pot of cultures and ethnic groups. The air of tolerance and wealth built on trade has enabled culture, science, and the Arts to flourish in the city for centuries. Today, Gdańsk remains a key meeting place and major tourist attraction in Poland. While the city boasts historic sites of enchanting beauty, it also has a major historic and social importance. In addition to its 1000-year history, the city is the place where the Second World War broke out as well as the birthplace of Solidarność, the Solidarity movement, which led to the fall of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe. The European Solidarity Centre www.ecs.gda.pl The European Solidarity Centre is a multifunctional institution combining scientific, cultural and educational activities with a modern museum and archive, which documents freedom movements in the modern history of Poland and Europe. The Centre was established in Gdańsk on November 8th 2007. Its new building was opened in 2014 on the anniversary of the August Accords signed in Gdańsk between the worker’s union “Solidarność” and communist authorities in 1980. The Centre is meant to be an agora, a space for people and ideas that build and develop a civic society, a meeting place for people who hold the world’s future dear. The mission of the Centre is to commemorate, maintain and popularise the heritage and message of the Solidarity movement and the anti-communist democratic op- position in Poland and throughout the world. -

Bartolini Brogi 2007.Indd

BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI SLAVISTICI – 4 – COMITATO SCIENTIFICO Giovanna Brogi Bercoff (Direttore), Michaela Böhmig, Stefano Garzonio (Presidente AIS), Nicoletta Marcialis, Marcello Garzaniti (Direttore esecutivo), Krassimir Stantchev COMITATO DI REDAZIONE Alberto Alberti, Giovanna Brogi Bercoff, Marcello Garzaniti, Stefano Garzonio, Giovanna Moracci, Marcello Piacentini, Donatella Possamai, Giovanna Siedina Titoli pubblicati 1. Nicoletta Marcialis, Introduzione alla lingua paleoslava, 2005 2. Ettore Gherbezza, Dei delitti e delle pene nella traduzione di Michail M. Ščerbatov, 2007 3. Gabriele Mazzitelli, Slavica biblioteconomica, 2007 Kiev e Leopoli: il “testo” culturale a cura di Maria Grazia Bartolini Giovanna Brogi Bercoff Firenze University Press 2007 Kiev e Leopoli : il testo culturale / a cura di Maria Grazia Bartolini, Giovanna Brogi Bercoff. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2007. (Biblioteca di Studi slavistici ; 4) http://digital.casalini.it/9788884536662 ISBN 978-88-8453-666-2 (online) ISBN 978-88-8453-665-5 (print) 947 (ed. 20) La collana Biblioteca di Studi Slavistici è curata della redazione di Studi Slavistici, rivista di proprietà dell’Associazione Italiana degli Slavisti (<http://epress.unifi.it/riviste/ss>). © 2007 Firenze University Press Università degli Studi di Firenze Firenze University Press Borgo Albizi, 28 50122 Firenze, Italy http://epress.unifi.it/ Printed in Italy INDICE G. Brogi Bercoff Prefazione 7 G. Siedina Il retaggio di Orazio nella poesia neolatina delle poetiche kieviane: alcuni modi della sua ricezione 11 D. Tollet La connaissance du judaïsme en Pologne dans l’œuvre de Gaudencjusz Pikulski, La méchanceté des Juifs (Lwów 1760) 37 Ks. Konstantynenko La vita artistica a Leopoli nel Seicento: l’arte delle icone 47 M.G. Bartolini Kiev e la formazione culturale di Skovoroda 61 A. -

St. John's Cathedral Wrocław

St. John’s Cathedral Wrocław The Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Wrocław, (Polish: Archikatedra św. Jana Chrzciciela, German: Breslauer Dom, Kathedrale St. Johannes des Täufers), is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Wrocław and a landmark of the city of Wrocław in Poland. The cathedral, located in the Ostrów Tumski district, is a Gothic church with Neo-Gothic additions. The current standing cathedral is the fourth church to have been built on the site. The cathedral was almost entirely destroyed (about 70% of the construction) during the Siege of Breslau and heavy bombing by the Red Army in the last days of World War II. Parts of the interior fittings were saved and are now on display at the National Museum in Warsaw. The initial reconstruction of the church lasted until 1951, when it was reconsecrated by Archbishop Stefan Wyszyński. In the following years, additional aspects were rebuilt and renovated. The original, conical shape of the towers was restored only in 1991. Wroclaw Town Hall The Old Town Hall (Polish: Stary Ratusz) of Wroclaw stands at the center of the city’s Market Square (rynek). Wroclaw is the largest city in western Poland and isthe site of many beautiful buildings. The Old Town Hall's long history reflects the developments that have taken place in the city over time since its initial construction. The town hall serves the city of Wroclaw and is used for civic and cultural events such as concerts held in its Great Hall. In addition to a concert hall, it houses a museum and a basement restaurant.