Elevating Form and Elevating Modulation (2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Songs

English Songs 18000 04 55-Vũ Luân-Thoại My 18001 1 2 3-Gloria Estefan 18002 1 Sweet Day-Mariah Carey Boyz Ii M 18003 10,000 Promises-Backstreet Boys 18004 1999-Prince 18005 1everytime I Close My Eyes-Backstr 18006 2 Become 1-Spice Girls 18007 2 Become 1-Unknown 18008 2 Unlimited-No Limit 18009 25 Minutes-Michael Learns To Rock 18010 25 Minutes-Unknown 18011 4 gio 55-Wynners 18012 4 Seasons Of Lonelyness-Boyz Ii Me 18013 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover-Paul S 18014 500 Miles Away From Home-Peter Pau 18015 500 Miles-Man 18016 500 Miles-Peter Paul-Mary 18017 500 Miles-Unknown 18018 59th Street Bridge Song-Classic 18019 6 8 12-Brian McKnight 18020 7 Seconds-Unknown 18021 7-Prince 18022 9999999 Tears-Unknown 18023 A Better Love Next Time-Cruise-Pa 18024 A Certain Smile-Unknown 18025 A Christmas Carol-Jose Mari Chan 18026 A Christmas Greeting-Jeremiah 18027 A Day In The Life-Beatles-The 18028 A dear John Letter Lounge-Cardwell 18029 A dear John Letter-Jean Sheard Fer 18030 A dear John Letter-Skeeter Davis 18031 A dear Johns Letter-Foxtrot 18032 A Different Beat-Boyzone 18033 A Different Beat-Unknown 18034 A Different Corner-Barbra Streisan 18035 A Different Corner-George Michael 18036 A Foggy Day-Unknown 18037 A Girll Like You-Unknown 18038 A Groovy Kind Of Love-Phil Collins 18039 A Guy Is A Guy-Unknown 18040 A Hard Day S Night-The Beatle 18041 A Hard Days Night-The Beatles 18042 A Horse With No Name-America 18043 À La Même Heure Dans deux Ans-Fema 18044 A Lesson Of Love-Unknown 18045 A Little Bit Of Love Goes A Long W- 18046 A Little Bit-Jessica -

M7, 7 Records and Powderworks 1970-1987

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS M7, 7 Records and Powderworks 1970-1987 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, JUNE 2019 M7 / 7 RECORDS BIRTHED DURING THE 1970 RECORD BAN, M7 WAS A SYDNEY-BASED LABEL SET UP AS A JOINT VENTURE BETWEEN THE MACQUARIE BROADCASTING SERVICE, THE HERALD AND WEEKLY TIMES LTD. AND FAIRFAX SUBSIDIARY AMALGAMATED TELEVISION SERVICES, OWNERS OF ATN-7. IN JULY 1970, WORLD BROADCASTING SYSTEM CHANGED ITS NAME TO M7 RECORDS PTY. LTD. M7 WAS DISTRIBUTED BY THE PAUL HAMLYN RECORD DIVISION (FROM JUNE 1971), THEN BY TEMPO (1974-1976), AND THEN ORGANISED ITS OWN DISTRIBUTION (1976-1978). ALLAN CRAWFORD WAS THE FIRST GENERAL MANAGER (1970-1972), FOLLOWED BY RON HURST (1972-1975). KEN HARDING JOINED M7 RECORDS IN 1973, BECOMING C.E.O. OF 7 RECORDS IN 1978, THE SAME YEAR HE SIGNED MIDNIGHT OIL TO THE LABEL. M7 RECORDS BECAME 7 RECORDS PTY. LTD. IN MAY 1978. AT THIS TIME, SALES AND DISTRIBUTION PASSED TO RCA. CATALOGUE PREFIXES MS M7 / SEVEN BGMS BLUE GOOSE MSA ARTIST OF AMERICA CHS CHAMPAGNE MSB BRITISH ARTISTS EUS EUREKA MSD SEVEN - 12” DISCO FSP FROG MSH HICKORY LRS LARRIKIN MSP PENNY FARTHING LW, LN M7 MSPD PENNY FARTHING – 12” DISCO RNO CREOLE MSS SPIRAL SAC AUSTRALIAN COUNTRY MST TRANSATLANTIC SS SATRIL MSY YOUNGBLOOD SUS STOCKADE M7 / 7 RECORDS 7” & 12” SINGLES LW 4512 C.C. RIDER / TRAVELLER S.C.R.A. 1971 LW 4522 HOUSE IN THE COUNTRY / LUCCA GREG BONHAM 6.71 LW 4532 IN VAIN THE CHRISTIAN / WHAT YOU’LL DO NOLAN 7.71 LW 4542 FRASER ISLAND / AUSTRALIA REVISITED REISSUED 1975 BY ‘TONI & ROYCE’ THE MEEPLES 6.71 LW -

NHS Finance Career Stories

NHS Finance Career Stories December 2015 2 NHS FINANCE CAREER STORIES Join the conversation www.futurefocusedfinance.nhs.uk @nhsFFF | #futurefocusedfinance [email protected] 3 CONTENTS: NHS FINANCE CAREER STORIES Sian Alcock NHS national graduate management trainee 9 Paul Baumann Chief financial officer, NHS England 11 Ben Bennett Director of business planning and resources, 13 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Mark Brooks Chief finance officer, Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust 15 Caroline Clarke Finance director and deputy chief executive, Royal Free London NHS FT 17 Jamie Foxton Deputy director of finance, Hull and East Yorkshire NHS Trust 19 Andrew Geldard Chief executive, North Essex Partnership University NHS FT 21 Kavita Gnanaolivu Manager, Ernst & Young 23 Kate Hannam Director of operations, North Bristol NHS Trust 25 Andy Hardy Chief executive officer, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust 27 Gemma McGeachie Senior manager – financial strategy, NHS England 29 Gill McKetterick Project manager, Mersey Care NHS Trust 31 Dinah McLannahan Senior business consultant, NHS Trust Development Authority 33 Loretta Outhwaite Chief finance officer, Isle of Wight Clinical Commissioning Group 35 Yarlini Roberts Chief finance officer, Kingston Clinical Commissioning Group 37 Adam Sewell-Jones Director of provider sustainability, Monitor 39 Justine Stalker-Booth Head of financial management specialised commissioning finance, 41 NHS England national team Paul Stocks Deputy director group finance -

Skills You Need to Change the World

Ciaran McHale A self-teachable training course to help you bring about significant change Skills You Need to Change the World Notes Manual (formatted for US Letter paper) CiaranMcHale.com— Copyright Copyright © 2009 Ciaran McHale. Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this training course and associated documentation files (the “Training Course”), to deal in the Training Course without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Training Course, and to permit persons to whom the Training Course is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions: • The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Training Course. • THE TRAINING COURSE IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WAR- RANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FIT- NESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE TRAIN- ING COURSE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE TRAIN- ING COURSE. The globe logo is from www.mapAbility.com. Used with permission. About the Author Ciaran McHale holds a Ph.D. in Computer Science from Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland. Since 1995, he has been working in the computer software industry as a consultant, trainer and author of training courses. His primary talent is the ability to digest complex ideas and re-explain them in simpler ways. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Round Midnight

Round Midnight Repertoire (Auszüge) Pop, Soul & Disco Lounge & Ballads Ballroom/Standardtanz Billie Jean (Michael Jackson) Walzer Don't know why (Norah Jones) Blurred Lines (Pharrell Williams) z.B.: Free (Deniece Williams) Celebration (Kool and the Gang) Fascination Home (Michael Buble) Crazy (Gnarls Barkley) I wonder why (Curtis Stigers) If I ain't got You (Alicia Keys) Crying at the Discotheque (Alcazar) Moonriver Killing me softly (Roberta Flack) Dance with somebody (Mando Diao) Over the rainbow Lovesong (Sara Bareilles) Firework (Katy Perry) Sous le ciel de Paris Put Your Records on (Corinne Bailey Rae) Gimme Gimme (ABBA) Stay with me (Sam Smith) Happy (Pharrell Williams) Foxtrott & Slow-Fox Turn on tune in (Freak Power) Happy Birthday (Stevie Wonder) z.B.: You give me something (James Morrison) Hung Up (Madonna) All of me Your Love is King (Sade) I feel good (James Brown) Autumn leaves I need a Dollar (Aloe Black) Cheek to Cheek How High the Moon I will survive (Gloria Gaynor) Latin & Brasil I’m so excited (Pointer Sisters) Night and Day On the sunny side It's raining men (Weather Girls) Ain't nobody Take the A Train Kiss (Prince) Bachata Rosa Lady Marmalade (Patti Labelle) Chan Chan Cha-Cha-Cha, Rhumba, Samba, Tango Let me entertain you (Robbie Williams) Clocks z.B.: Locked out of Heaven (Bruno Mars) Dos Gardenias Besame Mucho Mercy (Duffy) El cuarto de Tula Black Orpheus Never can say goodbye (Gloria Gaynor) Oye como va Brasil Proud Mary (Tina Turner) Vivir lo nuestro Relight my Fire (Take That) Girl from Ipanema Rock with You (Michael Jackson) Hernando's Hideaway Rolling in the Deep (Adele) Aquarela do Brasil Mas que Nada September (Earth Wind and Fire) Bahiafrika Perfidia Sex Bomb (Tom Jones) Forro do Xenhenhem Quizas, Quizas, Quizas Mas que Nada Sing it back (Moloko) So danco Samba Tombo Smooth Operator (Sade) Sway Something got me started (Simply Red) Tristeza Thriller (Michael Jackson) Treasure (Bruno Mars) Valerie (Amy Winehouse) Waterloo (ABBA) info & booking: Tel.: 0711 65 37 43 We are family (Sister Sledge) mail: [email protected] . -

Billboard-1975-12-06

08120 NEWSPAPER ;Sr110éR «76 tt* 156 151 R BB R SNYDER 3639 MARY A'JN 9R LEBANON 3036 81 St YEAR A Billboard Publication The International Music -Record -Tape Newsweekly December 6, 1975 $1 50 Ford Foundation In Disco Tour NEW DISK FORMULA? $180,000 Disk Outlay Sets Target L.A. Philharmonic By IS HOROWITZ Of 23 Cities NEW YORK -The Ford Founda- Atlantic's Glew By JIM MELANSON tion has disbursed $- 80,000 to 15 la- NEW YORK -A disco -themed Contract Disputed bels in the first nine months of its dance /concert package created by program to stimulate commercial Forum Keynoter Drew Cummings and quietly sup- By ROBEFT SOBEL recordings of serious works by living NEW YORK -'I he keynote ported by the Dimples discotheque GRC Assets Sold NEW YORK -Jos Angeles Phil- American composer;. speaker at the opening session of chain is being offered to arenas harmonic Orchestra management So far more than 40 LPs bearing Billboard's first International Disco throughout the East by the William To L.A. Agency claims it has achieved a union con- sponsored performances are being ForLm will be David Glew, vice Morris Agency. tract breakthrough providing that processed or have a ready been re- president of Atlantic Records. With the go -ahead signal given By DAVE DEXTER JR. only musicians taking part in leased. Glew's subject will be "Disco last week, the parties involved have LOS ANGELES -Sale of General recordings be paid for the session. Total commitment of the founda- Power: Myth Or Reality ?" (Continued on page 12) Recording Co.'s assets to the Ameri- The national symphonic formula tion project is $400,(00, and it is due The Forum opens at the Roosevelt can Variety International Agency requires all members of an estab- to run for three years or until the as- Hotel here Jan. -

Jazz/Swing/Bossa Ballad Country/Pop Rock LE REPERTOIRE

LE REPERTOIRE Jazz/Swing/Bossa My way (Interprète : Elvis) Ain't nobody here but us chickens (Louis Jordan) Sittin' on the dock of the bay (Otis Redding) All of me (Interprète : Ella Fitzgerald) Somethin’ stupid (Nicole Kidman Robbie Williams) Autum leaves (Joseph Kosma) Stand by me (Ben E King) Baby what you want me to do (Elvis) The river (Garth Brooks) Besame Mucho (Consuelo Velazquez) Timin' is everything (Garrett Hedlund) Blue bossa (Kenny Dorham) Walk on the wildside (Lou Reed) Blue Monk (The lonious Monk) What's goin' on (Marvin Gaye) Boogie in C What’s up (4 non blondes) Caldonia (Louis Jordan) What a wonderfull world (Bob Thiele & George David Call the doctor (JJ Cale) Weiss) Chega de Saudade (Joao Gilberto) Wonder of you (Elvis) Corcovado (Carlos Jobim) Yesterday (The Beatles) Desafinado (Joao Gilberto) You'll think of me (Keith Urban) Fly me to the moon (Frank Sinatra) Georgia on my mind (Ray Charles) Hit the road Jack (Ray Charles) Country/Pop Rock Mercy mercy mercy (Cannonball Aderley) Ain't no sunshine (Bill Withers) Misty (Erroll Garner) Big Boss man (Jimmy Reed) My funny Valentine (Interprète : Frank Sinatra) City of New Orleans (Steeve Goodman) Salut les Night and Day (Cole porter) amoureux Satin doll (Duke Ellington) Cocaine (version E. Clapton) So what (Miles Davis) Every breath you take (Police) Stella by starlight (Victor Young) Gentle on my mind (Glen Campbell) Tenor Madness (Sonny Rollins) Georgy Porgy (Toto) The girl from Ipanema (Carlos Jobim) Hard days night (The Beatles) Watermelon man (Herbie Hancock) Honky tonk woman (Rolling Stones) Hot'n Cold (Katy Perry) If I ai’ntgotyou (Alicia Keys) Ballad I got a woman (Ray Charles) Beat this summer (Brad Paisley) I'm alive (Version Kenny Chesnay & Dave Mathews) Bad Day (Daniel Powter) I'm yours (Jason Mraz) Budapest (Georges Ezra) I shot the sheriff (Bob Marley) Can't help falling in love (Elvis) It's a love thing (Keith Urban) Grenade (Bruno Mars) Lay down sally (Version E. -

A Prima Vista

A PRIMA VISTA a survey of reprints and of recent publications 2011/3 BROEKMANS & VAN POPPEL Van Baerlestraat 92-94 Postbus 75228 1070 AE AMSTERDAM sheet music: + 31 (0)20 679 65 75 CDs: + 31 (0)20 675 16 53 / fax: + 31 (0)20 664 67 59 also on INTERNET: www.broekmans.com e-mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS A PRIMA VISTA 2011/3 PAGE HEADING 03 PIANO LEFT-HAND, PIANO 2-HANDS 10 PIANO 4-HANDS 11 PIANO 6-HANDS, 2 AND MORE PIANOS 12 HARPSICHORD 13 ORGAN, KEYBOARD 14 ACCORDION 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 15 VIOLIN SOLO, 16 VIOLA SOLO, CELLO SOLO, DOUBLE BASS SOLO 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 16 VIOLIN with accompaniment 18 VIOLIN PLAY ALONG, VIOLA with accompaniment 19 CELLO with accompaniment, CELLO PLAY ALONG 20 VIOLA DA GAMBA with accompaniment 20 2 AND MORE STRING INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 24 FLUTE SOLO, OBOE SOLO, CLARINET SOLO, SAXOPHONE SOLO 25 TRUMPET SOLO, TROMBONE SOLO, HARMONICA (MOUTH ORGAN) SOLO 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 25 PICCOLO with accompaniment, FLUTE with accompaniment 26 FLUTE PLAY ALONG 28 OBOE with accompaniment, OBOE PLAY ALONG 29 COR ANGLAIS with accompaniment, CLARINET with accompaniment 30 CLARINET PLAY ALONG, SAXOPHONE with accompaniment 31 SAXOPHONE PLAY ALONG 32 TRUMPET with accompaniment, HORN with accompaniment, TROMBONE with accompaniment, TROMBONE PLAY ALONG 33 EUPHONIUM with accompaniment 2 AND MORE WIND INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 33 2 AND MORE WOODWIND INSTRUMENTS 35 2 AND MORE BRASS INSTRUMENTS 36 COMBINATIONS OF WOODWIND AND BRASS INSTRUMENTS 36 COMBINATIONS OF WIND AND STRING INSTRUMENTS 37 RECORDER 39 GUITAR 41 UKULELE 43 MANDOLIN, BANJO, HARP 44 PERCUSSION 45 MISCELLANEOUS, 47 SOLO VOICE, SOLO VOICE(S) AND/OR CHOIR WITH INSTRUMENTAL ACCOMPANIMENT 57 UNACCOMPANIED CHOIR 59 OPERA, OPERETTA, MUSICAL, ORATORIA, MASS (SCORES: POCKET-, STUDY-, FULL-, VOCAL-) 60 ORCHESTRA WITH AND WITHOUT INSTRUMENTAL SOLOISTS 62 BOOKS OF MUSICAL INTEREST compilation by Jan A. -

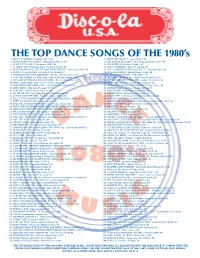

The Top Dance Songs of the 1980'S Was Compiled in Dec

THE TOP DANCE SONGS OF THE 1980’s 1. INTO THE GROOVE - Madonna (Sire) '85 71. NEED YOU TONIGHT - Inxs (Atlantic) '88 2. FASCINATION/FULL CIRCLE - Company B (Atlantic) '87 72. SHE DRIVES ME CRAZY - Fine Young Cannibals (I.R.S.) '89 3. PUMP UP THE JAM - Technotronic (SBK) '89 73. SUSSUDIO - Phil Collins (Atlantic) '85 4. IT TAKES TWO - Rob Base & D.J. E-Z Rock (Profile) '88 74. SILENT MORNING - Noel (4th & Bway) '87 5. NEVER GONNA GIVE YOU UP/TOGETHER FOREVER - Rick Astley (RCA)'88 75. LIKE A PRAYER/EXPRESS YOURSELF - Madonna (Sire) '89 6. PUMP UP THE VOLUME - M.A.R.R.S. (4th & Bway)'87 76. BUFFALO STANCE - Neneh Cherry (Virgin) '89 7. I WANNA DANCE WITH SOMEBODY - Whitney Houston (Arista) '87 77- WORK IT TO THE BONE - LNR (Profile) '89 8. THIS TIME I KNOW IT'S FOR REAL - Donna Summer (Atlantic) '89 78. YOU USED TO HOLD ME - Ralphi Rosario (Hot Mix) '87 9. YOU SPIN ME ROUND (LIKE A RECORD) - Dead or Alive (Epic) '85 79. SHOWER ME WITH YOUR LOVE - Surface (Columbia) '89 10. WHAT I LIKE ABOUT YOU - The Romantics (Epic) '80 80. ADDICTED TO LOVE - Robert Palmer (Island) '86 11. TRAPPED/I'M NOT GONNA LET - Colonel Abrams (MCA) '85,'86 81. CHAINS OF LOVE/A LITTLE RESPECT- Erasure (Sire) '88 12. MONY MONY - Billy Idol (Chrysalis) '81,'87 82. SO EMOTIONAL- Whitney Houston (Arista) '87 13. I LIKE YOU - Phyllis Nelson (Carrere) '86 83. EASY LOVER - Philip Bailey (Columbia) '84 14. I'LL HOUSE YOU -The Jungle Brothers (Idlers/Warlock)'89 84. -

No Song Artist/Composer 1 24K Magic

No Song Artist/Composer 1 24K Magic Bruno Mars 2 Adelaide's Lament (from Guys and Dolls) Frank Loesser 3 Adventure (from Do Re Mi) Jule Styne 4 Agony (from Into The Woods) Stephen Sondheim 5 Ah, But Underneath (from Follies) Stephen Sondheim 6 Ah! Sweet Mystery Of Life (from Naughty Marietta) Victor Herbert 7 Ain't There Anyone Here For Love? (from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes) Jule Styne 8 Alexander Hamilton (from Hamilton the Musical) Lin Manuel Miranda 9 All At Once Whitney Houston 10 All Good Gifts (from Godspell) Stephen Schwartz 11 All I Ask Adele 12 All I Ask Of You (from The Phantom Of The Opera) Andrew Lloyd Webber 13 All I Need Is The Girl (from Gypsy) Jule Styne 14 All Kinds of People (from Pipe Dream) Oscar Hammerstein, Richard Rodgers 15 All Or Nothing At All Frank Sinatra 16 All the pretty little horses Trad 17 All The Small Things Blink 182 18 All The Wasted Time (from Parade) Jason Robert Brown 19 All Things Bright And Beatiful (from Marry Me A Little) Stephen Sondheim 20 All Through The Night (from Anything Goes) Cole Porter 21 Almost A Love Song (from Victor/Victoria) Henry Mancini, Frank Wildhorn 22 Almost Real (from Bridges of Madison County) Jason Robert Brown 23 Alone Heart 24 Alone At The Drive‐In Movie (from Grease) Warren Casey 25 Alone In The Universe Stephen Flaherty 26 Alto's Lament Zina Goldrich 27 Always A Bridesmaid (from I Love You, You're Perfect, Now Change) Jimmy Roberts 28 Always On My Mind Michael Buble 29 Always True To You In My Fashion (from Kiss Me, Kate) Cole Porter 30 The American Dream Claude‐Michel -

Karaoke Songs

16.05.2018 - Cites d'or (instrumental).mp3 (Don't fear) The reaper - Blue Öyster Cult (made famous by ~) (karaoke).mp3 (Don't fear) The reaper - Blue Öyster Cult (made famous by ~) (karaoke)-1.mp3 (Everything I do) I do it for you - Bryan Adams (made famous by ~) (karaoke).mp3 (Everything I do) I do it for you - Bryan Adams (made famous by ~) (karaoke)-1.mp3 (I can't get no) Satisfaction - The Rolling Stones (made famous by ~) (karaoke).mp3 (I can't get no) Satisfaction - The Rolling Stones (made famous by ~) (karaoke)-1.mp3 (I can't get no) Satisfaction - The Rolling Stones (made famous by ~) (karaoke)-2.mp3 (I can't help) Falling in love with you - UB40 (made famous by ~) (karaoke).mp3 (Is this the way to) Amarillo - Tony Christie (made famous by ~) (karaoke).mp3 (Is this the way to) Amarillo - Tony Christie (made famous by ~) (karaoke)-1.mp3 (Is this the way to) Amarillo - Tony Christie (made famous by ~) (karaoke)-2.mp3 (Is this the way to) Amarillo - Tony Christie (made famous by ~) (karaoke)-3.mp3 (Is this the way to) Amarillo - Tony Christie (made famous by ~) (karaoke)-4.mp3 (I've had) The time of my life - Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (made famous by ~) (karaoke).mp3 (I've had) The time of my life - Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (made famous by ~) (karaoke).mp4 (I've had) The time of my life - Bill Medley And Jennifer Warnes (made famous by ~) (karaoke).mp3 (I've had) The time of my life - Bill Medley And Jennifer Warnes (made famous by ~) (karaoke)-1.mp3 (I've had) The time of my life - Bill Medley And Jennifer Warnes (made