Examining the Past, Transforming the Future VOL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Institutes

Summer Programs for High School Students 2015 Welcome Packet The Institutes June 14-June 21 June 21-June 28 June 28-July 5 July 5-July 12 July 12-July 19 July 19-July 26 July 26-August 2 Table of Contents Welcome to Summer at Georgetown 3 Your Pre-Arrival Checklist 4 Institute Program Calendar 5 Preparing for Your Summer at Georgetown 6 Enroll in NetID Password Station 6 Register for Your Institute(s) 6 Apply for Your GOCard 7 Submit Your Campus Life Forms 7 Learning the Georgetown Systems 8 During Your Program 10 Residential Living 13 On Campus Resources 15 Check-In Day 16 Campus Map 18 Check-Out 19 Georgetown University Summer Programs for High School Students 3307 M St. NW, Suite 202 Washington, D.C. 20057 Phone: 202-687-7087 Email: [email protected] 2 WELCOME TO SUMMER AT GEORGETOWN! CONGRATULATIONS! Congratulations on your acceptance to the Institute program at Georgetown University’s Summer Pro- grams for High School Students! We hope you are looking forward to joining us on the Hilltop soon. Please make sure you take advantage of the resources offered by Georgetown University! The Summer and Special Programs office, a part of the School of Continuing Studies at Georgetown Universi- ty, provides world renowned summer programs that attract students from around the United States of America and the world. As you prepare for your arrival on Georgetown’s campus, our staff is available to provide you with academic advising and to help you plan and prepare for your college experience at Georgetown. -

A New Appeal for Human Rights Atlanta, Georgia May 16, 2017 Jill

A New Appeal for Human Rights Atlanta, Georgia May 16, 2017 Jill Cartwright, Spelman College Asma Elhuni, Georgia State University Violeta Hernandez Padilla, Freedom University Serena Hughley, Spelman College Natalie Leonard, Georgia Institute of Technology Andalib Malit Samandari, Morehouse College Alma Olmedo-Fermin, Freedom University Daye Park, University of Georgia Jonathan Peraza, Emory University Maria Zetina, Agnes Scott College Charles Black, Second Chairman of the Atlanta Student Movement, Morehouse College Lonnie King, First Chairman of the Atlanta Student Movement, Morehouse College Dr. Roslyn Pope, Author of the 1960 Appeal for Human Rights, Spelman College Dr. Laura Emiko Soltis, Executive Director and Professor of Human Rights, Freedom University PREAMBLE On March 9, 1960, members of the Atlanta Student Movement published “An Appeal for Human Rights,” which denounced the discrimination they faced as black youth in the city of Atlanta. We, as students of conscience from Agnes Scott College, Clark Atlanta University, Emory University, Freedom University, the Georgia Institute of Technology, Georgia State University, Morehouse College, Spelman College, and the University of Georgia, take courage and inspiration from their legacy as we continue the struggle for human rights. Today, more than 57 years after the publication of the original Appeal for Human Rights, communities of color continue to bear the most severe violations of human rights here in the Deep South. In 1960, black people faced more overt forms of racial discrimination. But racism did not disappear - it evolved. Today, a powerful force underlying the intersecting forms of discrimination young people of color face is the assumption that they are criminals. This assumption takes on structural forms as prisons and immigrant detention centers, where racism is masked as law and order. -

Georgetown University Ryan A.Sakamoto Washington, D.C

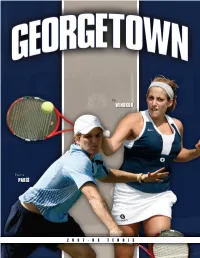

2007-08 SCHEDULE MEN’S TENNIS Jan. 18 VCU 4+1 Tournament & .................................all day Jan. 25 at Old Dominion ............................................... 1 p.m. Jan. 26 at Navy .................................................................. noon Feb. 1 at Penn ............................................................... 2 p.m. Feb. 2 at Maryland .......................................................... noon Feb. 9 at DePaul * .......................................................... noon Feb. 10 at Marquette * .................................................10 a.m. Feb. 23 YALE # ...................................................5:30 p.m. Mar. 1 BINGHAMTON # ................................5:30 p.m. Mar. 3 at Barry ................................................................. noon Mar. 4 at Lynn ..............................................................10 a.m. Mar. 7 at Florida Atlantic ............................................... noon Mar. 15 ST. JOHN’S * ................................................ noon Mar. 16 BOSTON COLLEGE ................................11 a.m. Kevin Mar. 20 at Richmond ................................................2:30 p.m. WALSHWALSH Mar. 26 UMBC ..........................................................2 p.m. Mar. 28 at George Washington ................................... 2 p.m. Apr. 4 VILLANOVA * .............................................1 p.m. Apr. 5 CONNECTICUT * ........................................ noon Liz Apr. 10 at James Madison ........................................... -

V~Vid. Social Sche

\I Vol. XLW. No. '\}g, I g GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY. WASHINGTON. D. C. Thursday. March 5. 1964 V~vid. Social Sche£!uJe HOYAMovesWithdrawal Ihghhgh~~TO!:?!ent VISIt At Picketed Council S nod The 1964 College Parents' Weekend festivities begin Y tomorrow night with registration of parents in New South Before a capacity crowd in Faculty Lounge. Registration will continue Saturday morn- Copley Lounge last Sunday ing. With the completion of registration, sample classes will night, The HOYA announced be conducted in history, philosophy, English and science. By its intentions to withdraw its attending mock classes, the parents will become acquainted representation from the Col- with academic standards ex- lege Student Council. pected of their sons. John Glavin. Associate Editor of the Campus newspaper and its cur- Politiesl Msneuverings The traditional Parents' rent delegate to the Council. pre- Weekend cocktail party is sented the decision of the 1964 Higllligllt Performsnee next on the agenda. The editorial board to resign its seat ·1 from the student body representa- cock tal party will commence tive organ at the Council's weekly Of/Re'S Fsvoretl "4" in McDonough Gymnasium imme- meeting. This past week the Inter diately after the sample classes. Glavin. a senior in the College national Relations Club sent At this event parents will have a and former Editor-in-Chief of The chance to speak with their son's HOYA, specified the reasons for a four-man delegation to the teachers and other faculty mem- the Board's decision. He said that Little United Nations As bers of the College. IN THE YARD •.• Ken Atchity withdraws HOYA from Stuoont. -

Shadow Class: College Dreamers in Trump's America APM Reports Transcript

Shadow Class: College Dreamers in Trump’s America APM Reports Transcript Stephen Smith: From American Public Media, this is an APM Reports documentary. Estefania Navarro: They don’t want people like me to dream, they just want working hands. President Trump is ending a program that allowed some undocumented young people to stay and work in the United States. For some, that may mean the end of a dream of going to college. Woman 1: I worked so hard to be here and it could be gone in like one second. Most Americans think young people brought here as children should be allowed to stay … but a vocal group wants them gone. Ruthie Hendrycks: They shouldn’t be in the country to begin with, much less in our colleges. In the coming hour, Shadow Class: College Dreamers in Trump’s America from APM Reports. Part 1 Protesters: “Immigrants Are Here to Stay! No Justice, No Peace. ” Denver high school students walked out of their classes after the Trump administration announced it would end a program that gives some undocumented young people temporary permission to stay in the United States. It was one of many protests around the country after Attorney General Jeff Sessions delivered the news: Jeff Sessions: Good morning. I am here today to announce that the program known as DACA that was effectuated under the Obama Administration is being rescinded. DACA is Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. It let young people brought to this country as children apply for temporary protection from deportation so they could work, or serve in the military, or go to college. -

A Study of the Impact of the Old Georgetown Act

BROWN_THE OLD GEORGETOWN ACT.DOCX 6/2/2014 5:06 PM Historic Districts and the Imagined Community: A Study of the Impact of the Old Georgetown Act Timothy F. Brown* INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 82 I: ZONING AND HISTORIC DISTRICTS ........................................... 84 A. The Rise of Historic Districts...................................... 85 B. Purpose of Historic Districts ....................................... 88 C. General Structure of Historic District Legislation .... 89 D. Arguments against Historic Districts ........................ 91 II: ZONING AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION WITHIN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ..................................................... 93 A. Advisory Neighborhood Commissions ........................ 93 B. Historic Preservation in the District .......................... 97 C. Zoning within the District ........................................ 100 PART III: GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY’S DEVELOPMENT AND CONFLICT WITH THE NEIGHBORHOOD ............................. 103 A. History of Conflict .................................................... 108 B. The Current Athletic Training Facility Project ....... 113 PART IV: CONCLUSION ............................................................. 117 * J.D. Candidate, 2014, Seton Hall University School of Law; Bachelor of Arts in Theology, 2009, Georgetown University. I am incredibly grateful to Professor Rachel Godsil for her support and help drafting and revising this Comment. I would also like to thank Professor -

Report of the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, And

REPORT OF THE WORKING GROUP ON SLAVERY, MEMORY, AND RECONCILIATION TO THE PRESIDENT OF GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY Washington, D.C. June 3, 2016 REPORT OF THE WORKING GROUP ON SLAVERY, MEMORY, AND RECONCILIATION TO THE PRESIDENT OF GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY Washington, D.C. June 3, 2016 Dr. John J. DeGioia, the president of Georgetown University, assembled the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation in September 2015. His charging letter outlined three tasks for the Working Group over the course of the academic year: Make recommendations on how best to acknowledge and recognize the university’s historical relationship to the institution of slavery. Examine and interpret the history of certain sites on the campus. Convene events and opportunities for dialogue on these issues. This report offers an overview of the Working Group’s activities, reflections on its mandate and work over the last academic year, and recommendations to the President on how the university community should continue its engagement with this history and its legacy. Although submission of this report concludes the Working Group’s responsibilities, the Working Group understands the report as offering direction and encouragement for the continuing efforts of the university. The report is organized in four sections. The first section sketches the Working Group’s activities over the seven months between its charging meeting on September 24, 2016, and the transmission of this report to the President. The second section offers the Working Group’s reflections on its seven months of consultation and deliberation, organized around the three concepts in the Working Group’s name: slavery, memory, and reconciliation. -

The President's Interfaith and Community Service Campus

THE PRESIDENT’S INTERFAITH AND COMMUNITY SERVICE CAMPUS CHALLENGE INSTITUTION LEAD STAFF GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY Christina Ciocca [email protected] Melody Fox Ahmed [email protected] 37th & O Streets, NW Lisa Pannucci [email protected] Ray Shiu [email protected] Washington, DC 20057 INSTITUTION LEAD STUDENT President John J. DeGioia Aamir Hussein, Student Interfaith Council President [email protected] http://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/projects/presidents-interfaith-challenge/ 1 UNIVERSITY OFFICES & CENTERS: • Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs • Kalmonavitz Initiative • Catholic Studies Department • McDonough School of Business • Center for Contemporary Arab Studies • Mission and Ministry • Center for Minority Educational Affairs • Mortara Center • Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding • Office of Campus Ministry • Center for Social Justice Research, Teaching and • Office of Communications Service • Office of the President • Center for Student Programs • Philosophy Department • Chaplains and Jesuits in Residence • Program for Jewish Civilization • The College • Program in Education, Inquiry and Justice • Faith in Action DC • Program on Justice and Peace • Faith Leaders for Community Change • Psychology Department • Film Studies Department • Residence Life • The Gelardin New Media Center • School of Continuing Studies • Government Department • School of Foreign Service • Georgetown Public Policy Institute • School of Nursing and Health Studies • GUWellness • Theology Department • History Department -

The Cardinal Newman Society

OPPOSITION NOTES AN INVESTIGATIVE SERIES ON THOSE WHO OPPOSE WOMEN’S RIGHTS AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH TABLE OF CONTENTS The Cardinal Newman Introduction . 1. Key Findings . 2 Origins . .2 . .Society Notre Dame: A Controversy . 2 without Consensus “ The most unhappily and inappropriately named society Issues . 3 on the planet” Finances . 6 Catholic Higher Education . .7 . in the United States INTRODUCTION Catholic Identity on Campus: . 8. In Decline? Holding on to Religious . .8 . he Cardinal Newman Society (CNS) claims that its mission is “to help renew and Exemptions strengthen Catholic identity in Catholic higher education,” but there are many Ex corde Ecclesiae . 9. Tclergy, staff at Catholic universities, students and laypeople who don’t recognize Tactics: Tricks of Perspective . 10 themselves in the organization’s vision of Catholic identity. Some, like the National Catholic Criticism . 13 Reporter, have pointed out the striking contrast between Cardinal Newman the man and Conclusion . .17 . the society that bears his name: “the most unhappily and inappropriately named society on the planet.”1 The Cardinal Newman Society devotes its energy to pointing out supposed breaches of dogma within Catholic universities, engineering negative publicity primarily by instigating letter-writing campaigns and posting online petitions. America magazine criticized the society’s “watchdog tactics” for employing a negative rather than positive definition of Catholicism — that is, it aims to prune away The Cardinal Newman Society is “destructive and perceived deviations from orthodoxy, rather than cultivating a Catholicism that is something antithetical to a spirit of unity in our commitment to more than mere conformism.2 serve society and the church.” Catholic academia has not always welcomed guidance from the CNS. -

Civil Rights Milestones WEDNESDAY, JUNE 3, 2015 from the Program Chairs

Celebration of Civil Rights Milestones WEDNESDAY, JUNE 3, 2015 From the Program Chairs “Someday they will have to open up that ballot box, and that will be our day of reckoning.” James Forman, SNCC, Executive Secretary Dear Program Attendee, We thank you for joining us as we revisit the indelible campaign for civil and voting rights in this country. After the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, it was apparent that there was still work to do for African- Americans to have full rights afforded as citizens of the United States. A fearless group of young people known as the Students Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) came to the city of Selma in Dallas County, Alabama, to organize and work with local leadership to push for the right to vote. Citizens of that community—parents and their children, young adults and seniors—were relentless in their efforts on non-violent resistance and activism. With the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, their efforts are now legend. We thank Charles S. Johnson III and Leland Ware for their informative CLE presentations, and pay homage to the 129 Georgia attorneys who were on the frontlines advancing civil rights and equal treatment for all, often at their peril. We are grateful for the leaders of the Selma to Montgomery March and for the work of members of our Selma panel: Joanne Bland, Sheyann Webb-Christburg, Dr. Bernard Lafayette, Charles Mauldin and Dr. Frederick Douglas 2 Celebration of Civil Rights Milestones PERKINS-HOOKER RICHARDSON Reese, for their commitment to take a stand and their courage in spite of the potential for personal harm. -

Welcome Home Alumni

Welcome Home Alumni Vol. LlI, No.8 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D.C. Thursday, October 31, 1968 Humphrey, Democrats Beat Opposition In Hilltop Voting Hubert Humphrey won The nine votes. Kennedy received 13 to-one margin. In the Pennsylvania HOYA's mock election last Friday write-ins and McCarthy received contest, incumbent Sen. Joseph with 41 percent of the vote. Rich- seven. Clark, a Democrat, won over Re ard Nixon trailed with 29.5 per- Only 33 Nursing School students publican Rep. Richard Schweiker, " cent and George Wallace with 3.9 -out of 256-participated in the again by a two-to-one margin. percent. Write-ins for Sen. Edward election. Nineteen cast their vote Sen. Wayne Morse beat Robert i Kennedy and Sen. Eugene McCar- for Nixon, eight for Humphrey, Packwood by a better than two-to thy surpassed the Wallace vote, four for Kennedy, and two for Mc one margin in the Oregon race. Kennedy obtaining approximately Carthy. None voted for Wallace. Democrat John Gilligan in Ohio, 11 percent and McCarthy six per- In the California senatorial race, topped Republican William Saxbe cent. Democrat Alan Cranston beat Re by slightly less than a two-to-one publican Max Rafferty by \l. two- margin. Some 1,273 students-about a quarter of the undergraduate stu dent body, participated in the elec tion. As far as a mock election is able to indicate, the Georgetown Directorship Goes campus is not as conservative as is commonly held. In four of the , ' five senatorial contests on the bal \ lot, liberal Democrats won by wide To Fordham Jesuit margins. -

For '64 Fall Semester the HOYA Has Recently Elected Its Editorial Board for Death Unexpectedly Ended Dr

Vol. XLl~, No. ~ 15 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D. C. Thursday, February 13, 1964 Dr. Ruby's Demise New Editors, Columns From Heart Attack Luxury Halls Slated Ends Long Service Vivify Expanded HOYA On February 1, sudden For '64 Fall Semester The HOYA has recently elected its editorial board for death unexpectedly ended Dr. the 175th Anniversary Year, 1964. The announcement of James S. Ruby's 26 years of ! the new board is made in conjunction with the expansion service to Georgetown. The of The HOYA to the status of an all-undergraduate news Executive Secretary of the paper. In the future, beginning with this issue, The HOYA Alumni Association suc will be distributed to and written by the undergraduate cumbed in his home, 4461 Green I wich Parkway, at the age of 58. students - College, Foreign Born in Helena, Montana, Ruby I Curley Science Series Service, Institute of Lan earned his Bachelor of Arts, Mas guages & Linguistics, Busi ters, and Doctoral degrees at Features MIT General Georgetown. During his tenure as ness Administration, and chairman of the GU English De I! On Science Socialism Nursing - of Georgetown partment he edited a collection of ! University. verse with Philip Kane, George i by Dick Conroy town Anthology. The fifth lecture of the At the outbreak of World War I New Columns II, Ruby was a lieutenant colonel I James Curley Science Series in the United States Army. He will be delivered in Gaston The 1964 editorial board includes was promoted to chief of the liaison NO MORE RUBBISH .•. will be filed behind New North when Hall next Tuesday by General one senior, nine juniors, five soph branch of the War Department.