The Truth Norm Account of Justification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nature of Moral Understanding Course Guide 2018-19

PHIL10099: Nature of Moral Understanding 2018/19 Course Guide Course Lecturer: David Levy ([email protected]) Office Location: Dugald Stewart 5.10 Office Hour: Tuesday 4.10-5.10pm Course Secretary: Ann-Marie Cowe ([email protected]) Contents 1. Course Aims and Objectives 2. Intended Learning Outcomes 3. Seminar Times and Locations 4. Seminar Content 5. Readings 6. Assessment 7. Useful Information Department of Philosophy School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences University of Edinburgh 1. Course Aims and Objectives There is a distinctive experience that humans have when they think about situations that seem to involve moral considerations. While these experiences may be amenable to theoretical formalisation, there is important philosophical reflection to be done without theory. What do people understand when they understand a situation as demanding moral consideration, reflection or decision? This course aims to make progress with this and related questions and in the process complement our other courses in ethics and ethical theory. The central question with which this course is concerned is: what is the nature of the understanding someone has when they engage with their moral concerns? These moral concerns are considered to arise in relatively ordinary situations of the kinds presented in life, literature and film. These situations include decisions about what to do in a situation; wondering about one’s life; questions of whether one is under a moral obligation; contemplation of shame or guilt. In this sense, this course is a philosophical examination of various phenomena—moral phenomena—about which philosophical theories are constructed. The main goals will be to focus on the nature of the understanding we have of these phenomena with a view to clarifying which are their essential features and which do not distinguish them. -

Aristotelian Virtue Ethics and the Self-Absorption Objection

ARISTOTELIAN VIRTUE ETHICS AND THE SELF-ABSORPTION OBJECTION ARISTOTELIAN VIRTUE ETHICS AND THE SELF-ABSORPTION OBJECTION BY JEFFREY D’SOUZA, M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright Jeffrey D’Souza, March 2017 McMaster University DOCTOR OF ARTS (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (Philosophy) TITLE: Aristotelian Virtue Ethics and the Self-Absorption Objection AUTHOR: Jeffrey D’Souza, M.A. (Ryerson University); H.B.A. (University of Toronto) SUPERVISOR: Professor Mark Johnstone NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 155 ii Lay Abstract: In this dissertation, I advance a neo-Aristotelian account of moral motivation that is immune from what I call the “self-absorption objection.” Roughly, proponents of this objection state that the main problem with neo- Aristotelian accounts of moral motivation is that they wrongly prescribe that our ultimate reason for acting virtuously is the fact that doing so is good for us. In an attempt to sidestep this objection, I offer what I call the altruistic account of motivation. On this account, the virtuous agent’s main reason for acting virtuously is based on her desire to act in accordance with a particular conception of the good life, where what makes such a conception good is not that it is good for her, but rather good, qua human goodness. iii Abstract: Aristotelian eudaimonism – as Daniel Russell puts it – is understood as two things at once: it is the final end for practical reasoning, and it is a good human life for the one living it. -

Nature of Moral Understanding 2016/17 Course Guide

PHIL10099: Nature of Moral Understanding 2016/17 Course Guide Course Lecturer: David Levy ([email protected]) Office Location: Dugald Stewart 5.10 Office Hour: Tuesday 4-5 Course Secretary: Ann-Marie Cowe ([email protected]) Contents 1. Course Aims and Objectives 2. Intended Learning Outcomes 3. Seminar Times and Locations 4. Seminar Content 5. Readings 6. Assessment 7. Useful Information Department of Philosophy School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences University of Edinburgh 1. Course Aims and Objectives There is a distinctive experience that humans have when they think about situations that seem to involve moral considerations. While these experiences may be amenable to theoretical formalisation, there is important philosophical reflection to be done without theory. What do people understand when they understand a situation as demanding moral consideration, reflection or decision? This course aims to make progress with this and related questions and in the process complement our other, more formal, courses in moral philosophy. The central question with which this course is concerned is: what is the nature of the understanding someone has when they engage with their moral concerns? These moral concerns are considered to arise in relatively ordinary situations of the kinds presented in life, literature and film. These situations include decisions about what to do; wondering how to live; questions of whether one is under a moral obligation; contemplation of shame or guilt. In this sense, this course is a philosophical examination of various phenomena—moral phenomena—about which philosophical theories are constructed. The main goals will be to focus on the nature of the understanding we have of these phenomena with a view to clarifying which are their essential features and which do not distinguish them. -

The Truth Norm Account of Justification

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo THE TRUTH NORM ACCOUNT OF JUSTIFICATION Alexander Greenberg Trinity Hall University of Cambridge 6th July 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE TRUTH NORM ACCOUNT OF JUSTIFICATION ABSTRACT This thesis is about the relationship between a belief being justified and it being true. It defends a version of the view that the fundamental point of having a justified belief is to have a true one. The particular version of that view it defends is the claim that belief is subject to a truth norm – i.e. a norm or standard that says that one should believe something if and only if it’s true. It claims that belief being subject to such a truth norm can explain which beliefs count as justified and which do not. After introducing the idea of a truth norm (Ch. 1), the argument of my thesis involves two main stages. Part One of the thesis (Chs. 2-3) contains the first stage, in which I argue that my way of arguing for a truth norm, on the basis of its explanatory role in epistemology, is much more likely to be successful than a more popular way of arguing for a truth norm, on the basis of its explanatory role in the philosophy of mind. Part Two (Chs. 4-7) contains the second stage, in which I argue that the truth norm can indeed explain justification in the way I’ve outlined. -

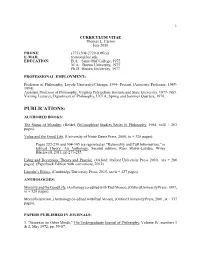

Tom Carson CV

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Thomas L. Carson July 2018 PHONE: (773) 508-2729 (Office) E-MAIL [email protected] EDUCATION: B.A. Saint Olaf College, 1972 M.A. Brown University, 1975 Ph.D. Brown University, 1977 PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT: Professor of Philosophy, Loyola University/Chicago, 1994- Present (Associate Professor, 1985- 1994). Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 1977-1985. Visiting Lecturer, Department of Philosophy, UCLA, Spring and Summer Quarters, 1976. PUBLICATIONS: AUTHORED BOOKS: The Status of Morality, (Reidel, Philosophical Studies Series in Philosophy, 1984, xxiii + 203 pages). Value and the Good Life, (University of Notre Dame Press, 2000, ix + 328 pages). Pages 222-239 and 304-305 are reprinted as “Rationality and Full Information,” in Ethical Theory: An Anthology, Second edition, Russ Shafer-Landau, Wiley Blackwell. 2013, pp 277-285. Lying and Deception: Theory and Practice, (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2010, xix + 280 pages) (Paperback Edition with corrections, 2012) Lincoln’s Ethics, (Cambridge University Press, 2015, xxvii + 427 pages). ANTHOLOGIES: Morality and the Good Life, (Anthology co-edited with Paul Moser), (Oxford University Press: 1997, vi + 528 pages). Moral Relativism ,(Anthology co-edited with Paul Moser), (Oxford University Press, 2001, ix + 337 pages). PAPERS PUBLISHED IN JOURNALS: 1. "Strawson on Other Minds," The Undergraduate Journal of Philosophy, Volume IV, numbers 1 & 2, May 1972, pp. 59-67. 2 2. "Happiness and Contentment: A Reply to Benditt," The Personalist, Volume 59, Number 1, January 1978, pp. 101-107. 3. "Happiness and the Good Life," Southwestern Journal of Philosophy, Volume IX, Number 3, November 1978, pp. 73-88. 4. "Happiness and the Good Life: A Reply to Mele," Southwestern Journal of Philosophy, Volume X, Number 2, Summer 1979, pp.