SID LVO 1Lign? (Revised January

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing the Role of Scale Economies and Imperfect Competition in the Context of Agricultural Trade Liberalisation: a Canadian Case Study

ASSESSING THE ROLE OF SCALE ECONOMIES AND IMPERFECT COMPETITION IN THE CONTEXT OF AGRICULTURAL TRADE LIBERALISATION: A CANADIAN CASE STUDY Franqois Delorme and Dominique van der Mensbrugghe CONTENTS Introduction .............................................. 206 I. The implementation of scale economies in WALRAS ............ 207 A. Scale-economy parameters ............................ 209 B. Pricing strategies ................................... 21 1 II. Empirical results ....................................... 218 A. Perfect competition ................................. 220 B. Scale economies and oligopolistic behaviour ............... 222 111. Concluding remarks.. ................................... 225 Technical Annex ........................................... 230 Bibliography .............................................. 233 FranCois Delorme is an Administrator with the Growth Studies Division and Dominique van der Mensbrugghe was a Trainee with the Growth Studies Division. The authors are grateful to John P. Martin, Val Koromzay and Peter Sturm for many perceptive suggestions and substantial comments on an earlier draft. They are also indebted to Kym Anderson, Jean-Marc Burniaux, Avinash Dixit, Robert Ford, Richard Harris, lan Lienert, James Markusen, Victor Norman, J. David Richardson, Benoit Robidoux, Jeff Shafer and Anthony J. Venables for valuable discussions and comments during the course of this work. 205 INTRODUCTION One of the key characteristics of the WALRAS model [as described in Burniaux et a/. (1989)l is that it assumes that all markets are perfectly competi- tive and production takes place under constant returns to scale. In this case, supply curves are flat', although they shift as input prices change. Until recently, this modelling strategy was adopted by most applied general equilibrium (AGE) modellers, since such models are relatively easy to build and their properties are well understood. Simulations of trade liberalisation with such models tend to show rather "small" welfare gains, typically of the order of 1 per cent of GNP or less. -

Excess Capacity.Pdf

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Todorova, Tamara Preprint Is There Excess Capacity Really? Theoretical and Practical Research in Economic Fields Suggested Citation: Todorova, Tamara (2015) : Is There Excess Capacity Really?, Theoretical and Practical Research in Economic Fields, ISSN 2068–7710, ASERS Publishing, s.l., Vol. 6, Iss. 2 (12) (Winter), pp. 127-143 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/157217 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Is There Excess Capacity Really? Tamara Todorova American University in Bulgaria Excess capacity is viewed as a distinctive feature and an essential inefficiency of monopolistic competition as the large-group case of imperfect competition. -

ECO 610: Lecture 4 Horizontal Boundaries of the Firm Horizontal Boundaries of the Firm: Outline

ECO 610: Lecture 4 Horizontal Boundaries of the Firm Horizontal Boundaries of the Firm: Outline • Long-run average cost (LRAC) curve • Shape of the LRAC: economies and diseconomies of scale • Optimal plant size: minimum efficient scale (MES) • MES, market demand, and market structure • Horizontal boundaries vs. vertical boundaries • Reasons why economies of scale might occur Product-level economies Plant-level economies Firm-level economies • Economies of scope Choosing a plant size: Long-run average costs and the firm’s planning curve • Now let’s get serious about opening up a fast-food restaurant near the UK campus. You find a location and choose a franchise chain. You set up a meeting with company representatives, at which they open a briefcase and pull out some spreadsheets and blueprints which contain the following information: • [see next slide] • Then they ask you: How many customers do you envision yourself wanting to serve each day? • Answer #1: Duh? • Answer #2: Well, I’ve done some demand forecasting and I envision serving roughly X meals per day. The LRAC curve and economies of scale • Given sufficient time to plan and execute, firms can vary all inputs optimally for whatever scale of operation they desire. • So in reality, firms can choose from many different plant sizes. The LRAC curve is the envelope of all the SRATC curves associated with each different plant size. • The LRAC curve tells us the minimum possible average total cost for producing each output level. • The shape of the LRAC curve tells us how per unit costs change as the firm changes the scale of its operations. -

The Estimation of Minimum Efficient Scale of the Port Industry Abstract Terminal Scale Has Been the Subject of Discrete Episodes of Hotly Contested Policy Debates

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Plymouth Electronic Archive and Research Library The estimation of minimum efficient scale of the port industry Abstract Terminal scale has been the subject of discrete episodes of hotly contested policy debates. From the perspective of port authorities or governments, knowing the Minimum Efficient Scale (MES) is salient, because they sometimes determine the port development or expansion based on the port capacity or the existing size of the terminal. Notwithstanding the importance of knowing the exact MES, extant literature has not managed to estimate MES in the port industry. This study aims to estimate the MES in the port industry in South Korea in order to identify whether Container Terminal Operators (CTOs) are under economies of scale, constant economies of scale or diseconomies of scale; we explore a bottom point of the average cost curve in order to suggest an adequate scale for the port industry in Korea. The finding demonstrates that undercapacity may be a strong issue in Korean container ports. However, CTOs in Busan port are in an overcapacity area given the market demand of container throughput in 2013, which is approximately 25 times larger than the estimated MES; in fact, all CTOs in Busan port operate at more than 20% of MES. This study then can provide port policy makers with a helpful tool to derive ex-ante MES level at the terminal designing stage and to adjust ex-post port investment decisions at the additional port capacity designing stage, which may contribute to avoiding overcapacity. -

Advertising As a Barrier to Entry?

\\ WORKING PAPERS ADVERTISING AS A BARRIER TO ENTRY? Carl Shapiro WORKING PAPER NO. 7 4 July 1982 nc Bore� ofEcooomics working papers are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical commenl All data cootained in them are in the publicooaD. This includes informatiou obtainedby theCommioo which has become part ofpublic record. The analyses and concltmollS set forthare those of the111d aJ6Irs do not necessarily reflect the viewsother of membersof the Bureau of Economics, other Comm issioo orstaff, theCommissi on itself. Upon uest,siBgle copies ofthe paper will be provided. References in pubUcatioos to FfCBureau ofEcooomics working papers by FfCecon Oill&s (other than acknowledgement by a writer that he h access to such uopubUshed materials) should be cleared with theauthor to protect the tentative character of these papers. BUREAUOF ECONOMICS FEDERALTRADE COMMISSION WASHINGTON,DC 20580 Advertising as a Barrier to Entry? Carl Shapiro* June, 1982 This paper has been prepared for the F.T.C. 's Product Differentiation study. I thank David Scheffman for his advice and support. The views presented here are those oi the author alone, and not necessarily those of the F.T.C. staff nor the Commission members themselves. I. Introduction: The Importance of Entry Barriers Economists are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of the conditions of entry into a market in determining the performance of that market. It is fast becoming conventional wisdom that a firm with a large market share may have quite limited market power if there are no barr iers to entry into its market. The absence of barr iers to entry implies that any attempt by the dominant firm (or firms) to raise prices and earn monopoly prof its will be met (rapidly) by new entry and the erosion of market share. -

Nrr196-05 Economies of Scale and Vertical Integration In

NRR196-05 ECONOMIES OF SCALE AND VERTICAL INTEGRATION IN THE INVESTOR-OWNED ELECTRIC UTILITY INDUSTRY by Herbert G. Thompson, Ph.D. David Alan Hovde Louis Irwin Christensen Associates with Mufakharul Islam Graduate Research Associate, NRRI and Project Manager Kenneth Rose, Ph.D. Senior Institute Economist, NRRI The National Regulatory Research Institute The Ohio State University 1 080 Carmack Road Columbus, Ohio 43221-1002 614/292-9404 January 1996 This report was prepared by Christensen Associates for The National Regulatory Research Institute (NRRI) with funding provided by participating member commissions of the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC). The views and opinions of the authors do not necessarily state or reflect the views, opinions, or policies of the NRRI, the NARUC, or NARUC member commissions. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report analyzes the nature of costs in a vertically-integrated electric utility. The major findings of this study provide new insights into the operations of the vertically-integrated electric utility and support a number of results and trends reported in earlier research on economies of scale and density. The results also provide insights for policy makers dealing with electric industry restructuring issues such as competitive structure and mergers. Overall, the results indicate that for a majority of firms in the industry, average costs would not be reduced through the expansion of generation, numbers of customers, or the delivery system. Evidently, the combination of the benefits from large-scale technologies, managerial experience, coordination, or load diversity have been exhausted by the larger firms in the industry. However, the evidence strongly supports the notion that many firms would benefit from reducing their generation-to-sales ratio and by increasing sales to their existing customer base. -

Weighing Operating Efficiency When Enforcing Antitrust Law

Fordham Law Review Volume 49 Issue 5 Article 13 1981 Note: Economies of Scale: Weighing Operating Efficiency when Enforcing Antitrust Law Laraine L. Laudati Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Laraine L. Laudati, Note: Economies of Scale: Weighing Operating Efficiency when Enforcing Antitrust Law, 49 Fordham L. Rev. 771 (1981). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol49/iss5/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECONOMIES OF SCALE: WEIGHING OPERATING EFFICIENCY WHEN ENFORCING ANTITRUST LAW "[I]t has been the law for centuries that a [person] may set up a business in a country town too small to support more than one, although thereby ... [intending] to ruin some one already there and [succeeding in that] intent. In such a case [the competitor] is not held to act 'unlawfully and without justifiable cause .... The reason, of course, is that the doctrine generally has been accepted that free competi- tion is worth more to society than it costs, and that on this ground the infliction of the damage is privileged." * INMODUCION Economists have long recognized the antitrust dilemma that it is impossible to promote perfect competitionI when large economies of scale are present.' Because economists generally believe that anti- trust policy should reinforce the achievement of scale economies,3 they encourage only workable competition when large scale econo- mies exist.4 Courts, although traditionally emphasizing populist goals in antitrust enforcement, such as protecting small business,' recently * Vegelaln v. -

Basic Market Structure Slides the Structure-Conduct-Performance Model

Networks, Telecommunications Economics and Strategic Issues in Digital Convergence Prof. Nicholas Economides Spring 2005 Basic Market Structure Slides The Structure-Conduct-Performance Model • Basic conditions: technology, economies of scale, economies of scope, location, unionization, raw materials, substitutability of the product, own elasticity, cross elasticities, complementary goods, location, demand growth • Structure: number and size of buyers and sellers, barriers to entry, product differentiation, horizontal integration, vertical integration, diversification • Conduct: pricing behavior, research and development, advertising, product choice, collusion, legal tactics, long term contracts, mergers • Performance: profits, productive efficiency, allocative efficiency, equity, product quality, technical progress • Government Policy: antitrust, regulation, taxes, investment incentives, employment incentives, macro policies 2 Costs Total costs: C(q) or TC(q) Variable costs: V(q) Fixed costs: F(q) = F, constant C(q) = F + V(q) Average total cost: ATC(q) = C(q)/q Average variable cost: AVC(q) = V(q)/q Average fixed cost: ATC(q) = F/q. ATC(q) = F/q + AVC(q) Marginal cost: MC(q) = C′(q) = dC/dq = V′(q) = dV/dq 3 The marginal cost curve MC intersects the average cost curves ATC and AVC at their minimums. Remember, MC is the cost of the last unit. When MC is below average cost (ATC or AVC), it tends to drive the average cost down, i.e. the slope of ATC (or AVC) is negative. When MC is above average cost (ATC or AVC), it tends to drive the average cost up, i.e. the slope of ATC (or AVC) is positive. AC and MC are equal at the minimum of AC. -

Industrial Organization Entry Costs, Market Structure and Welfare

ECON 312: Determinants of Firm & Market Size 1 Industrial Organization Entry Costs, Market Structure and Welfare Your economics courses has thus far examined how firms behave under differing market structures, while Industrial Organization has examined their interaction strate- gically with respect to one another. But a good question to ask at this juncture is how was the market structure arrived at, and what is the consequent size of the constituent firm(s). Why does a market have only one, two, three, ... firms? Why not more or less? We will now examine how technology and market size influence the firm size and industry concentration within a market. Let us first refresh our memory of some measures of market power, and industry concentration. The most typical and natural way of measuring market power is the Lerner Index which is a weighted average of each firm’s margin, and where the weights are defined by each firm’s respective market share, that is, n X pi − MCi L = s i p i=1 i where each firm is indexed by i, and market share is si. Note that I have assumed that each firm can have a different price, and marginal cost. For concentration, the most typical measure is to measure the sum of the market shares of the largest of n firms, that is, m X Cm = si i=1 where as before, market share for firm i is si, and where m is the number of larger firms or those that commands the largest market share. But another measure is the Herfindahl Index which square the market share before summing it. -

The Estimation of Minimum Efficient Scale of the Port Industry

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Arts and Humanities Plymouth Business School 2016-07 The estimation of minimum efficient scale of the port industry Seo, Y-J http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/4592 10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.04.012 Transport Policy All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. The estimation of minimum efficient scale of the port industry Abstract Terminal scale has been the subject of discrete episodes of hotly contested policy debates. From the perspective of port authorities or governments, knowing the Minimum Efficient Scale (MES) is salient, because they sometimes determine the port development or expansion based on the port capacity or the existing size of the terminal. Notwithstanding the importance of knowing the exact MES, extant literature has not managed to estimate MES in the port industry. This study aims to estimate the MES in the port industry in South Korea in order to identify whether Container Terminal Operators (CTOs) are under economies of scale, constant economies of scale or diseconomies of scale; we explore a bottom point of the average cost curve in order to suggest an adequate scale for the port industry in Korea. The finding demonstrates that undercapacity may be a strong issue in Korean container ports. -

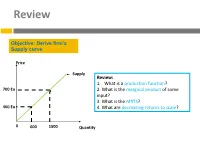

Review: 1. What Is a Production Function? 700 Eu • 2

Review Objective: Derive firm’s Supply curve Price Supply Review: 1. What is a production function? 700 Eu • 2. What is the marginal product of some input? 3. What is the MRTS? 400 Eu • 4. What are decreasing returns to scale? 0 600 1500 Quantity Review How much does it cost the firm to produce q units? The firm’s cost function specifies the cost to produce q units Total costs are determined by the production function and the costs of inputs But there are many different combinations of inputs that can produce q units. The firm’s problem is to choose the combination of inputs that minimizes costs. The Cost Function Example 1. A firm requires a single input to produce output, with production function f(L)=√L. If the wage is w=$10, how much does it cost to produce 3 units? How much does it cost to produce Q units? Example 2: A firm needs 2 workers and 1 machine to produce a single unit. The wage is w = 5 and rent is r = 10. What is the cost of producing 10 units? What is the cost function? Example 3: A firm can produce 1 unit of output with either 2 workers or with 1 machine. If the wage is w=5 and rent is r = 5. What is the cost of producing 10 units? Derive the cost function TC(Q)? The Cost Function When the firm hires L workers and K units of capital the total cost is: w = wage rate L = Quantity of Labor r = price per unit of capital services K = Quantity of Capital The total costs are: TC wL rK The Cost Function If are many different combinations of inputs that can produce Q units. -

Notes on Market Structure

Stern School of Business Fall 2003 Prof. N. Economides Notes on Market Structure 1. Taxonomy of objects of study in a market ! Basic conditions ! Structure ! Conduct ! Performance ! Government Policy Basic conditions: technology, economies of scale, economies of scope, location, unionization, raw materials, substitutability of the product, own elasticity, cross elasticities, complementary goods, location, demand growth. Structure: number and size of buyers and sellers, barriers to entry, product differentiation, horizontal integration, vertical integration, diversification. Conduct: pricing behavior, research and development, advertising, product choice, collusion, legal tactics, long term contracts, mergers. Performance: profits, productive efficiency, allocative efficiency, equity, product quality, technical progress. Government Policy: antitrust, regulation, taxes, investment incentives, employment incentives, macro policies. 2. The Structure-Conduct-Performance Model Basic Conditions Structure Government Policy Conduct Performance 2 Costs Total costs: C(q) or TC(q) Variable costs:V(q) Fixed costs: F(q) = F, constant C(q) = F + V(q) Average total cost: ATC(q) = C(q)/q Average variable cost: AVC(q) = V(q)/q Average fixed cost: ATC(q) = F/q. ATC(q) = F/q + AVC(q) Marginal cost: MC(q) = C′(q) = dC/dq = V′(q) = dV/dq The marginal cost curve MC intersects the average cost curves ATC and AVC at their minimums. See Figure 1. Remember, MC is the cost of the last unit. When MC is below average cost (ATC or AVC), it tends to drive the average cost down, i.e. the slope of ATC (or AVC) is negative. See point A. When MC is above average cost (ATC or AVC), it tends to drive the average cost up, i.e.