“Recruits and Comrades” in “A War of Ambition”: Mennonite Immigrants in Late 19Th

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6.4 Land Drainage & Ground Water

6.0 Infrastructure Development 6.4 Land Drainage & Ground Water Poor drainage has always been a major problem in the study region. It confronted and defeated some of the first settlers during the 1870s, and for many years prevented widespread settlement of the Red River Valley, despite the richness of its soil and the ease in which the open prairie grasslands could be broken and cultivated. The long-standing problem of land drainage existed for several reasons. The many creeks and rivers flowing from the highlands in the eastern part of the region regularly spilled their banks during the annual spring melt, flooding the farmland on the 'flats' in the western part of the study region. Due to the extreme flatness of the land in the Red River Valley, and the impervious nature of the clay subsoil, this water tended to remain on the surface, and only very slowly drained away or evaporated. Such waterways, which flowed into semi- permanent marshes, without outlets, were known as ‘blind creeks’ and there were a number of them in the study region. Drainage ditches and canals were constructed in the valley by the early 1880s, and these initially succeeded in draining off much of the excess surface water. The Manning Canal, in particular, constructed in 1906-08 in the area south of the Seine River, facilitated the draining of several large permanent marshes in that area. Some of the earliest drainage projects involved the Seine River and Mosquito Creek near St. Malo, and the 'flats' south of Dominion City. However, as new farms were cleared and roads constructed in the hitherto undrained territory of the eastern highland regions, more and more runoff was directed into the upstream drainage canals, overloading them and choking them with silt and vegetation. -

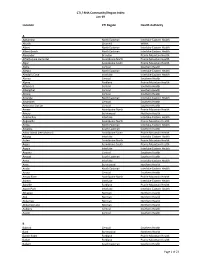

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

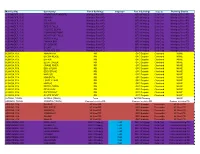

Community MUNICIPALITY ABIGAIL MUNICIPALITY of BOISSEVAIN

Community MUNICIPALITY ABIGAIL MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON ADELPHA MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON AGHAMING INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS AGNEW RM OF PIPESTONE AIKENS LAKE INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS AKUDLIK TOWN OF CHURCHILL ALBERT RM OF ALEXANDER ALBERT BEACH RM OF VICTORIA BEACH ALCESTER MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON ALCOCK RM OF REYNOLDS ALEXANDER RM OF WHITEHEAD ALFRETTA HAMIOTA MUNICIPALITY ALGAR RM OF SIFTON ALLANLEA MUNICIPALITY OF GLENELLA-LANSDOWNE ALLEGRA RM OF LAC DU BONNET ALLOWAY RIVERDALE MUNICIPALITY ALMASIPPI RM OF DUFFERIN ALPHA RM OF PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE ALPINE MUNICIPALITY OF SWAN VALLEY WEST ALTAMONT MUNICIPALITY OF LORNE ALTBERGTHAL MUNICIPALITY OF RHINELAND AMANDA RM OF ALEXANDER AMARANTH RM OF ALONSA AMBER RM OF MINTO-ODANAH AMBROISE SETTLEMENT RM OF PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE AMERY Not within a MUNICIPALITY ANAMA BAY INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS ANEDA RM OF LAC DU BONNET ANGUSVILLE RM OF RIDING MOUNTAIN WEST ANOLA RM OF SPRINGFIELD APISKO LAKE INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS ARBAKKA RM OF STUARTBURN ARBOR ISLAND MUNICIPALITY OF BOISSEVAIN-MORTON ARDEN MUNICIPALITY OF GLENELLA-LANSDOWNE ARGEVILLE RM OF COLDWELL ARGUE MUNICIPALITY OF GRASSLAND ARGYLE RM OF ROCKWOOD ARIZONA MUNICIPALITY OF NORTH NORFOLK ARMSTRONG SIDING MUNICIPALITY OF WESTLAKE-GLADSTONE ARNAUD MUNICIPALITY OF EMERSON-FRANKLIN ARNES RM OF GIMLI Community MUNICIPALITY ARNOT INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS ARONA RM OF PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE ARROW RIVER PRAIRIE VIEW MUNICIPALITY ASESSIPPI RM OF RIDING MOUNTAIN WEST ASHBURY RM OF WHITEHEAD -

Designated Reservoir Areas Regulation, M.R. 22/88 R

THE WATER RESOURCES ADMINISTRATION ACT LOI SUR L'AMÉNAGEMENT HYDRAULIQUE (C.C.S.M. c. W70) (c. W70 de la C.P.L.M.) Designated Reservoir Areas Regulation Règlement sur les zones réservoirs reconnues Regulation 22/88 R Règlement 22/88 R Registered January 15, 1988 Date d'enregistrement : le 15 janvier 1988 Definitions Définitions 1 In this regulation, 1 Les définitions qui suivent s'appliquent au présent règlement. "permit" means a permit issued under section 16 of the Act; (« permis ») « ligne de démarcation » Ligne de démarcation du bien-fonds détenu par la Couronne à des fins "severance line" means the boundary line of the d'inondation en rapport avec un réservoir. land held by the Crown for the purpose of ("severance line") flooding in connection with a reservoir. (« ligne de démarcation ») « permis » Permis délivré en vertu de l'article 16 de la Loi . ("permit") Requirements for a permit Délivrance de permis 2 The minister shall not issue a permit in 2 Le ministre ne peut délivrer de permis respect of a building or structure within a visant un bâtiment ou un ouvrage situé dans une designated reservoir area unless zone réservoir reconnue que dans les cas suivants : (a) the building or structure is for agricultural a) le bâtiment ou l'ouvrage est destiné à des fins purposes or for water control works; or agricoles ou à des ouvrages d'aménagement hydraulique; (b) the designated reservoir area, or that part thereof in which the building or structure is or b) la zone réservoir reconnue, ou la partie de la will be situated, is under a town planning zone dans laquelle le bâtiment ou l'ouvrage est ou scheme, a planning scheme, or a development sera situé, est visée par le schéma plan. -

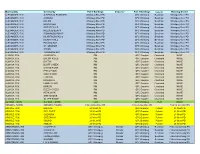

(ALEXANDER) Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M

Municipality Community Part 9 Buildings Inspector Part 3 Buildings Inspector Planning District ALEXANDER, R.M. ALBERT (ALEXANDER) Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. AMANDA Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. BELAIR Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. BIRD RIVER Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. GREAT FALLS Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. HILLSIDE BEACH Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. IRONWOOD POINT Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. MCARTHUR FALLS Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. MURRAY HILL Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. PINAWA BAY Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. ST. GEORGE Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. STEAD Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. TRAVERSE BAY Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Beacham Winnipeg River PD ALONSA, R.M. AMARANTH RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. BACON RIDGE RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. BAFFIN RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. BLUFF CREEK RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. CRANE RIVER RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. EBB & FLOW RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. EDDYSTONE RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. -

Municipality Community Part 9 Buildings Inspector Part 3 Buildings Inspector Planning District ALEXANDER, R.M

Municipality Community Part 9 Buildings Inspector Part 3 Buildings Inspector Planning District ALEXANDER, R.M. ALBERT (ALEXANDER) Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. AMANDA Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. BELAIR Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. BIRD RIVER Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. GREAT FALLS Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. HILLSIDE BEACH Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. IRONWOOD POINT Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. MCARTHUR FALLS Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. MURRAY HILL Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. PINAWA BAY Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. ST. GEORGE Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. STEAD Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALEXANDER, R.M. TRAVERSE BAY Winnipeg River PD OFC Winnipeg Dela Cruz Winnipeg River PD ALONSA, R.M. AMARANTH RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. BACON RIDGE RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. BAFFIN RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. BLUFF CREEK RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. CRANE RIVER RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. EBB & FLOW RM OFC Dauphin Chartrand NONE ALONSA, R.M. -

DIRECTORY of SERVICES the Carillon

Section B Thursday August 11, 2016 www.thecarillon.com Let ME help YOU Let ME help YOU grow your business in The grow your business in Steinbach and the Southeast Steinbach and the Southeast Multi-media Advertising Options Multi-media Advertising Options • PRINT • ONLINE • MOBILE • PRINT • ONLINE • MOBILE • FLYER DISTRIBUTIONS Carillon Classifi eds • FLYER DISTRIBUTIONS JANET KEHLER PROFESSIONAL SERVICES • PROPERTY • EMPLOYMENT • MISCELLANEOUS MICHELLE LAJOIE The Carillon DIRECTORY OF SERVICES The Carillon 01 7-2 2 3 www.friesendrillers.com 9 1 PERCHUK R.V. TRAILER SITES 75 and RENTALS We Meet By Accident GRANITE LAKE ONTARIO Hail damage? Hyy 17 30 km East of Manitoba/Ontario border 2013 Chev Silverado 4x4 We can help! Fire Road #27 95,000 Kms. Call for price! JOSH LOEWEN Ph. 1-807-733-2287 204-346-9047 Ph 204-326-3491 204-326-2485 56 Hwy 12 N 1-32 Email: [email protected] Cel 1 807-467-1737 Join us for our annual Back to School Tune up Employment Employment Employment for the kids - August 29th to September 2nd. Hanover Screw Pile Opportunities Opportunities Opportunities No charge Helical Screw Pile Intallation for kids Foundation Repair 0 - 18 Trouble www.hanoverscrewpile.ca with foul 204-326-3400 balls? Foundation Water Proofing RECEPTIONIST We can Mobile Welding Loewen Chiropractic Clinic Kevin Druet Excavations The Town of Sainte-Anne is currently accepting applications for the position www.loewenchiropracticclinic.com help! JESSE LOEWEN of full-time Receptionist to enter into function as soon as possible. Xrays on site. Ph 204-326-4005 204-388-9037 Open Monday to Saturday The receptionist will be responsible for providing front desk and Email: [email protected] [email protected] administrative support for the Town of Sainte-Anne. -

Province of Manitoba

PART V. Province of Manitoba (Entered Confederation July 15, 1870) Minister of Public Works—Hon. Geo. A. Lieutenant-Governor—Sir James Aikins. Grierson. Private Secretary—E. Herbert Coleman. Provincial Treasurer — Hon. Edward SENATORS IN DOMINION PARLIA- MENT Brown. Hon. R. Watson, Portage la Prairie; Hon. Minister of Education—Hon. Dr. R. S. W. H. Sharpe, Manitou; Hon. Aime Thornton. Benard, Winnipeg, and Hon. L. Mc- Means, Winnipeg; Hon. G. H. Bradbury, Attorney-General, Minister of Telephones Winnipeg; Hon. F. L. Shaffner. Boisse- vain. and Telegraphs—Hon. T. H. Johnson. MEMBERS IN HOUSE OF COMMONS Minister of Agriculture and Immigra- PROVINCIAL EXECUTIVE tion—Hon. Valentine Winkler. Hon. T. C. Norris (Premier), President of Council, Provincial Land Commis- Provincial Secretary and Municipal Com- sioner, Railway Commissioner. missioner—Hon. Dr. J. W. Armstrong. CONSTITUENCIES, MEMBERS AND ADDRESSES (Fifteenth Legislature) First Session) Hon. J. B. Baird, Speaker; A. W. Morley, Clerk Legislative Assembly; John Macdougall, ,Sergeant-at-Arms LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY, 1919 Elected August 6, 1915 Constituencies Members P. O. Address (1 Arthur John Williams Melita 2 Assiniboia John W. Wilton Winnipeg: 3 Beautiful Plains Wm. R. Wood Franklin 4 Birtle G. H. J. Malcolm Birtle 5 Brandon Stephen Clement Brandon 6 Carillon Albert Prefontaine St. Pierre 7 Cypress Andrew W. Myles Treherne 8 Dauphin Wm. J. Harrington... Dauphin 9 Deloraine Hon. R. S. Thornton Deloraine 10' Dufferin E. A. August Carman 11 Elmwood Thos. G. Hamilton Elmwood 1/2 Emerson J. D. Baskerville Dominion City 1)3 Gilbert Plains Wm. £>. Findlater Gilbert Plains 14 Gimli T. D. Perley Winnipeg 15 Gladstone Hon. J. W. -

Gazette GDU Manitoba Vol

THEManitoba azette Gazette GDU Manitoba Vol. 147 No. 3 January 20, 2018 ● Winnipeg ● le 20 janvier 2018 Vol. 147 no 3 Table of Contents GOVERNMENT NOTICES HALCROW to THORDARSON ................................... 13 HALCROW to THORDARSON ................................... 13 Under The Change of Name Act: HAMPSON to BEATTIE ............................................... 13 ALCHAIBIN to ALCHAIBIN ....................................... 13 HONGORO to HONGORO .......................................... 13 ALHANSHOUL to AL MATAR AL HANSHOUL ....... 13 JACOBSEN to JACOBSEN .......................................... 13 ALLAN to ALLEN ........................................................ 13 LAMBERT to ZABOLOTNY ....................................... 13 BALFOUR to HART ..................................................... 13 LUCIER to LUCIER ...................................................... 13 BAYVA to BAYYA ........................................................ 13 MARTENS WIEBE to FALK ........................................ 13 BEILIS to BAILEYS ..................................................... 13 MOHAMMED to MOHAMMED ................................. 13 BEILIS to BAILEYS ..................................................... 13 MOHAMMED to YOUNG ........................................... 13 BEILIS to BAILEYS ..................................................... 13 PARNELL to JOHNSON ............................................... 13 BEILIS to BAILEYS ..................................................... 13 PAULENKO to PAULENKO -

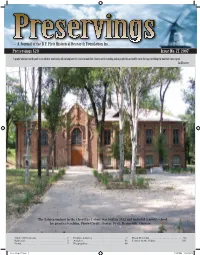

Preservings $20 Issue No. 27, 2007

~ A Journal of the D. F. Plett Historical Research Foundation Inc. Preservings $20 Issue No. 27, 2007 “A people who have not the pride to record their own history will not long have the virtues to make their history worth recording; and no people who are indifferent to their past need hope to make their future great.” — Jan Gleysteen The Lehrerseminar in the Chortitza Colony was built in 1912 and included a model school for practice teaching. Photo Credit: George Dyck, Beamsville, Ontario. Table Of Contents .......................................... 2 Feature Articles .............................................. 4 Book Reviews .............................................. 96 Editorial .......................................................... 3 Articles ......................................................... 34 Letters to the Editor ................................... 104 News............................................................... 3 Biographies .................................................. 80 Preservings 27.indd 1 2/15/2008 2:16:09 PM In this Issue Preservings 2007 In this issue we are taken the length and breadth Table of Contents of the Dutch-North German-Russian Mennonite scattering across the world and over time. Sjouke Voolstra’s article about early Dutch conservatives RUSSIAN MENNONITES IN THE DIASPORA offers rare and interesting insights that point to some conservative ways still practiced that have their Editorial .............................................................................................................3 -

Lettersofrusticu00curr.Pdf

THE LETTERS OF RUSTICUS INVESTIGATIONS IN MANITOBA AND THE NORTH-WEST, FOR THE BENEFIT OF INTENDING EMIGRANTS. A SERIES OF LETTERS FROM THE SPECIAL COMMISSIONER OF THE "MONTREAL WITNESS." i • 1 1 $ ^ John Dougall & Son, 33 to 37 St. Bonaventure Street, at r. INTRODUCTION. Two or three years ago the Montreal Witness who, from the nature of things, cannot be all devoted much attention to the question of finding speculators. work for the unemployed in agricultural pursuits, Having been born and brought up on a and opened its columns to descriptions of the backwoods farm, and having afterwards cleared attractions of different parts of the country. It one for myself, the proprietors of the Witness was s on found that the hope and interest of the thought I would be a suitable person to send to people centered largely in the prairies of the the North- West to glean information among the North-West, and numerous were the letters of settlers there, which might be of use to many of enquiry with regard to tbat land of promise. In the readers of that paper, as some of them or the published accounts within reach there was their friends might be thinking of removing to much evidence of one-sidedness and some con- that land of promise. It was their desire that I tradiction. Another defect which was too ap- should avoid as much as possible the beaten parent in almost all North-Western literature paths in which others had sought for information, was the fact that the writers were not practical and strike out afresh for myself, and to this end agriculturists themselves, and it might be as I was given carte blanche both as to time and wise to send a doctor to examine and test a steam means to be used. -

Environmental Pollutants - Sources

ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTANTS - SOURCES In this section: 1.0 EMISSIONS INVENTORIES .............................................................1 2. AGRICULTURE ................................................................................9 3. FORESTRY .................................................................................... 18 4. LARGE INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL EMITTERS ........................ 25 5. CONTAMINATED SITES AND MINE TAILINGS .................................. 54 6.0 COMMON CONTAMINANTS ASSOCIATED WITH VARIOUS ACTIVITIES ............................................................................... 100 EMISSIONS INVENTORIES 1.0 EMISSIONS INVENTORIES An emissions inventory is a database that lists, by source, estimated amounts of air pollutants discharged into the atmosphere of a community during a given time period. 1 Environment Canada estimates emissions to air of some common known or suspected carcinogens from a wide range of sources in Manitoba every year:2 • Fine particulates (PM 2.5 ). PM 2.5 is produced by many different sources, but mostly from those burning fossil fuels. It is a known carcinogen – there is very strong evidence that breathing in PM 2.5 increases your chance of getting cancer. • Volatile organic compounds (VOCs). VOCs are produced by human activities like industrial processes, burning fossil fuels or wood, or off-gassing from fuels, paints, solvents and cleaning products. There are many natural sources as well, including odors produced by trees and plants, forest fires, animal waste and even microbes. Environment Canada’s estimate is for VOCs as a group, but only some of these are linked to cancer, for example, benzene, ethylbenzene, formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, butadiene, and others. • Lead and cadmium. Lead and cadmium are heavy metals that remain in the environment for a long time and can be transported long distances when emitted to the air. They can occur naturally, but most of the lead and cadmium pollution comes from burning fossil fuels and metal mining and refinery processes.