Calypsos of Decolonization Ray Funk [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hrh : So Many Thoughts on Royal Style Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HRH : SO MANY THOUGHTS ON ROYAL STYLE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Elizabeth Holmes | 336 pages | 07 Dec 2020 | St Martins Press | 9781250625083 | English | New York, United States HRH : So Many Thoughts on Royal Style PDF Book With all eyes on them, the duchesses select clothes that send a message about their values, interests, and priorities. Dec 7, By Chloe Foussianes. I see hints of the Queen in Kate, too, with her very sensible approach to clothing. Tell Us Where You Are:. July 14, The Swedish princess celebrated Princess Victoria of Sweden's 41st birthday in a casual-chic floral print dress. But for that engagement photocall, she was still very much figuring it out. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano. By Megan Harney and Charlotte Chilton. She went shopping by herself and picked out the off-the-rack suit at Harrods that matched her ring and her eyes. By Katie Frost. Product Reviews. When you add that extra layer of meaning, it becomes so important, and I hope people see that in this book. Holmes: I spent a decade on staff at The Wall Street Journal covering the business of fashion, exploring the messaging and the power of clothes. Check out this adorable ruffled party dress she wore at just three years old. The Prince and the Queen rocked fantastic vacation style during their tour of the South Pacific. As royal fans know, Princess Diana eventually found her sartorial footing around the same time her marriage began to dissolve. November 13, Looking beautifully regal, the brunette royal wore a purple gown with lace detailing on the skirt and sequin pumps that sparkled as much as her tiara. -

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected]

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] ARTIST Various TITLE Calypso Craze 1956-57 And Beyond LABEL Bear Family Productions CATALOG # BCD 16947 PRICE-CODE GK EAN-CODE ÇxDTRBAMy169472z FORMAT 6-CD/1-DVD Box-Set (LP-size) with 176-page hardcover book GENRE Calypso CD 173 tracks, 484:23 min. DVD 14 chapters, ca 86 min. INFORMATION In the standard history of American pop music, the 1950s are a parade of rock icons: Bill Haley, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Little Richard, Elvis Presley. But after the demise of the great dance bands of the 1940s, rock 'n' roll didn't actually secure its position as the Next Big Thing until quite late in the day. For a few short months, in fact, it seemed that rock might be just another pas- sing fad – and that calypso was here to stay. From late 1956 through mid-1957, calypso was everywhere: not just on the Hit Parade, but on the dance floor and the TV, in movie theaters and magazines, in college student unions and high school glee clubs. There were calypso card games, clothing lines, and children's toys. Calypso was the stuff of commercials and comedy routines, news reports and detective novels. Nightclubs across the country hastily tacked up fishnets and palm fronds and remade themselves as calypso rooms. Singers donned straw hats and tattered trousers and affected mock-West Indian 'ahk-cents.' And it was Harry Belafonte – not Elvis Presley – who with his 1956 album 'Calypso' had the first million-selling LP in the history of the record industry. -

Calypso, Education and Community in Trinidad and Tobago: from the 1940S to 2011 1

Tout Moun Caribbean Journal of Cultural Studies http://journals.sta.uwi.edu/toutmoun/index.asp © The University of the West Indies, Department of Literary Cultural & Communication Studies Calypso, Education and Community in Trinidad and Tobago: From the 1940s to 2011 1 Calypso, Education and Community in Trinidad and Tobago from the 1940s to 2011 GORDON ROHLEHR I Introduction This essay has grown out of an address delivered on Wednesday January 28, 2009, at a seminar on the theme “Education through Community Issues and Possibilities for Development.” It explores the foundational ideas of Dr. Eric Williams about education as a vehicle for decolonization through nation-building, most of which he outlined in Education in the British West Indies,(1) a report that he prepared under the auspices of the Caribbean Research Council of the Caribbean Commission between 1945 and 1947, and published in 1950 in partnership with the Teachers’ Economic and Cultural Association [TECA] of Trinidad and Tobago. Drawing heavily upon De Wilton Rogers’s The Rise of the People’s National Movement,(2) this essay will detail Williams’s association with the TECA and its education arm, The People’s Education Movement [PEM] between 1950 and 1955 when Williams made the transition from research to politics via lectures, first at the Port-of-Spain library, then before massive crowds in Woodford Square. It will also explore the issues of education, community, and nation-building during the early Tout Moun ▪ Vol. 2 No. 1 ▪ October 2013 2 Gordon Rohlehr years of the PNM’s first term in office, when Williams struggled to sell his ideas(2) about educational reform and development to a skeptical and sometimes hostile hierarchy of entrenched interests. -

Symbolism of the Longest Reigning Queen Elizabeth II From1952 To2017

الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطية الشعبية Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Symbolism of the Longest Reigning Queen Elizabeth II from1952 to2017 Dissertation submitted to the Department of English as a partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in (LC) Literature and Civilization Presented by Supervised by Ms. Leila BASSAID Mrs. Souad HAMIDI BOARD OF EXAMINERS Dr. Assia BENTAYEB Chairperson Mrs. Souad HAMIDI Supervisor Dr. Yahia ZEGHOUDI examiner Academic Year: 2016-2017 Dedication First of all thanks to Allah the most Merciful. Every challenging work needs self efforts as well as guidance of older especially those who were very close to our heart, my humble efforts and dedications to my sweet and loving parents: Ali and Soumya whose affection, love and prayers have made me able to get such success and honor, and their words of encouragement, support and push for tenacity ring in my ears. My two lovely sisters Manar and Ibtihel have never left my side and are very special, without forgetting my dearest Grandparents for their prayers, my aunts and my uncle. I also dedicate this dissertation to my many friends and colleagues who have supported me throughout the process. I will always appreciate all they have done, especially my closest friends Wassila Boudouaya, for helping me, Fatima Zahra Benarbia, Aisha Derouich, Fatima Bentahar and many other friends who kept supporting and encouraging me in everything for the many hours of proofreading. I Acknowledgements Today is the day that writing this note of thanks is the finishing touch on my dissertation. -

Big Steve's Grill to Close After 12 Years

VOLUME 24 NUMBER 6 PLAINVILLE’S HOMETOWN CONNECTION MARCH 2021 When Aunt Jemima Came to Plainville Big Steve’s Grill To Close After 12 Years Big Steve’s Grill has been a town fixture for 12 years. Customers could dine in, a take out window or dining outside when weather permits. With a heavy heart to announce, we will be forced to close on March 8th. The landlord will demolish the building to build apartments and commercial space. Owner Steve Andrikis said, “We would like to take this time to thank all our loyal customers for their support and patronage over the past 12 years, especially throughout this pandemic in which we remained open to make sure we were able to provide our dedicated customers with a hot meal and a blazing smile. “All the best to you guys and thank you for all the wonderful food cooked and Read the fascinating story on page 26 of hospitality given over the years,” Marc Ouellette wrote. Aunt Jemima’s visit to Plainville 65 years ago... Is This the Biggest Snowman in Town? I am located on Williams Street and growing bigger every time we have another snow storm! Call 860-747-4119 and let us know if you have a bigger snowman. Hometown Connection’s Items of interest department. PAGE 2 PLAINVILLE’S HOMETOWN CONNECTION MARCH 2021 Worth the DANCINGLY YOURS trip from Dressing Dancers since 1989! Dance Supplies anywhere! 125 East Street, Rt. 10 Plainville, CT 860-793-1077 Dance Shoes & www.dancinglyyours.com Shoes & Tights Papa Pizza Apparel [email protected] **1st Anniversary** Pointe shoe fittings are always 10% by appointment only. -

Celebrating Our Calypso Monarchs 1939- 1980

Celebrating our Calypso Monarchs 1939-1980 T&T History through the eyes of Calypso Early History Trinidad and Tobago as most other Caribbean islands, was colonized by the Europeans. What makes Trinidad’s colonial past unique is that it was colonized by the Spanish and later by the English, with Tobago being occupied by the Dutch, Britain and France several times. Eventually there was a large influx of French immigrants into Trinidad creating a heavy French influence. As a result, the earliest calypso songs were not sung in English but in French-Creole, sometimes called patois. African slaves were brought to Trinidad to work on the sugar plantations and were forbidden to communicate with one another. As a result, they began to sing songs that originated from West African Griot tradition, kaiso (West African kaito), as well as from drumming and stick-fighting songs. The song lyrics were used to make fun of the upper class and the slave owners, and the rhythms of calypso centered on the African drum, which rival groups used to beat out rhythms. Calypso tunes were sung during competitions each year at Carnival, led by chantwells. These characters led masquerade bands in call and response singing. The chantwells eventually became known as calypsonians, and the first calypso record was produced in 1914 by Lovey’s String Band. Calypso music began to move away from the call and response method to more of a ballad style and the lyrics were used to make sometimes humorous, sometimes stinging, social and political commentaries. During the mid and late 1930’s several standout figures in calypso emerged such as Atilla the Hun, Roaring Lion, and Lord Invader and calypso music moved onto the international scene. -

Table of Contents

National Discourse on Carnival Arts Report by Ansel Wong, October 2009 1 2 © Carnival Village, Tabernacle 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. Contact details for further information: Shabaka Thompson CEO Carnival Village, Tabernacle Powis Square London W11 2AY Tel: +44 (0) 20 7286 1656 [email protected] www.Carnivalvillage.org.uk 3 This report is dedicated to the memory of David Roussel-Milner (Kwesi Bachra) 18 February 1938 – 28 October 2009 4 Executive Summary Introduction The Carnival Village, The ELIMU Paddington Arts Carnival Band, the Victoria and Albert Museum and HISTORYtalk hosted the National Discourse on Carnival from Friday 2 October to Sunday 4 October 2009 with a number of post-conference events lasting for the duration of the month of October. The programme was delivered through two strands – ROOTS (a historical review and critical analysis of Carnival in London from 1969) and ROUTES (mapping the journey to artistic and performance excellence for Carnival and its related industries) - to achieve the following objectives: Inform Carnival Village‟s development plans Formulate an approach to and build a consensus on Carnival Arts Identify and develop a strategic forum of stakeholders, performers and artists Recognise and celebrate artistic excellence in Carnival Arts Build on the legacies of Claudia Jones and other Carnival Pioneers The Programme For the duration of the event, there were two keynote presentations; the first was the inaugural Claudia Jones Carnival Memorial Lecture delivered by Dr Pat Bishop and the second was delivered by Pax Nindi on the future of Carnival. -

Chapter 2 Defining Calypso

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/45260 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Charles, Clarence Title: Calypso music : identity and social influence : the Trinidadian experience Issue Date: 2016-11-22 71 Chapter 2 Defining Calypso In the absence of conclusive evidence that points to a singular ethnic source of origin, analysis is launched from the premise that calypso music is a product of the ethno-cultural mosaics found within the boundaries in which it emerged, was developed, and exists as various strains with features that are characteristic, sometimes unique to its host mosaic. Etymology and Anthropology So far efforts by researchers to establish the origin of calypso music as a definite song type have been inconclusive. The etymology of the term ‘calypso’ in reference to that song type has proven to be as equally mysterious and speculation remains divided among contributors. This chapter of the study will touch upon literature that speculates about these issues relative to the emergence and development of the song type on the island of Trinidad. At one end of the discussion about origin Lamson (1957, p. 60) has reported the use of French melodic material in calypso, and Raphael De Leon aka The Roaring Lion (1987) has argued in Calypsos from France to Trinidad: 800 Years of History, that the genre was given the pseudonym ‘calypso’ some time in 1900, and derives from French ‘ballade’ created in 1295. He has also publicly asserted that, there is no evidence to support the claim that it is either a variant of African folk songs or that it was invented by African slaves in Trinidad. -

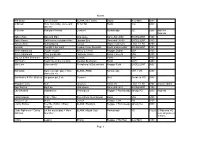

Sheet1 Page 1 809 Band Jam Session BLANK (Hit

Sheet1 809 Band Jam Session BLANK (Hit Factor) Digital Near Mint $200 Al Brown Here I Am baby, come and Tit for Tat Roots VG+ $200 take me Al Senior Bonopart Retreat Coxsone Rocksteady VG $200 Old time Repress Baby Cham Man and Man Xtra Large Dancehall 2000 EXCELLENT $100 Baby Wayne Gal fi come in a dance free Upstairs Ent. Dancehall 95-99 EXCELLENT $100 Banana Man Ruling Sound Taurus Digital clash tune EXCELLENT $250 Benaiah Tonight is the night Cosmic Force Records Roots instrumental EXCELLENT $150 Beres Hammond Double trouble Steely & Clevie Reggae Digital VG+ $150 Beres Hammond They gonna talk Harmony House Roots // Lovers VG+ $150 Big Joe & Bim Sherman Natty cale Scorpio Roots VG+ $400 Big Youth Touch me in the morning Agustus Buchanan Roots VG++ $200 Billy Cole Extra careful Recrational & Educational Reggae Funk EXCELLENT $600 Bob Andy Games people play // Sun BLANK (FRM) Rocksteady VG+ // VG $400 shines for me Bob Marley & The Wailers I'm gonna put it on Coxsone SKA Good+ to VG- $350 Brigadier Jerry Pain Jwyanza Roots DJ EXCELLENT $200 answer riddim Buju Banton Big it up Mad House Dancehall 90's EXCELLENT $100 Carl Dawkins Satisfaction Techniques Reggae // Rocksteady Strong VG $200 Repress Carol Kalphat Peace Time Roots Rock International Roots VG+ $300 Chosen Few Shaft Crystal Reggae Funk VG $250 Clancy Eccles Feel the rhythm // Easy BLANK (Randy's) Reggae // Rocksteady Strong VG $500 snappin Clyde Alphonso // Carey Let the music play // More BLANK (Muzik City) Rocksteady VG $1200 El Flip toca VG Johnson Scorcher pero sin peso -

The Swell and Crash of Ska's First Wave : a Historical Analysis of Reggae's Predecessors in the Evolution of Jamaican Music

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2014 The swell and crash of ska's first wave : a historical analysis of reggae's predecessors in the evolution of Jamaican music Erik R. Lobo-Gilbert California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Lobo-Gilbert, Erik R., "The swell and crash of ska's first wave : a historical analysis of reggae's predecessors in the evolution of Jamaican music" (2014). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 366. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/366 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Erik R. Lobo-Gilbert CSU Monterey Bay MPA Recording Technology Spring 2014 THE SWELL AND CRASH OF SKA’S FIRST WAVE: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF REGGAE'S PREDECESSORS IN THE EVOLUTION OF JAMAICAN MUSIC INTRODUCTION Ska music has always been a truly extraordinary genre. With a unique musical construct, the genre carries with it a deeply cultural, sociological, and historical livelihood which, unlike any other style, has adapted and changed through three clearly-defined regional and stylistic reigns of prominence. The music its self may have changed throughout the three “waves,” but its meaning, its message, and its themes have transcended its creation and two revivals with an unmatched adaptiveness to thrive in wildly varying regional and sociocultural climates. -

Chapter 4 Calypso’S Function in Trinidadian Society

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/45260 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Charles, Clarence Title: Calypso music : identity and social influence : the Trinidadian experience Issue Date: 2016-11-22 137 Chapter 4 Calypso’s Function in Trinidadian Society In this chapter, the potential of calypso music and its associated institutions to construct and maintain identity, and to instigate social reform will be discussed. I will argue that affiliation with those institutions and participation in their related activities, many of which have already been outlined, have fostered the development and transmission of an ingrained tradition. I will also attempt to show that the ingrained tradition has been part of an independent arm of the rigid socio-cultural, socio-psychological and socio-political machinery that rose up to repudiate and deconstruct colonial ideology. In order to accomplish these goals, functions of calypso music within Trinidadian, West Indian and global communities at home and abroad will be examined and correlated to concepts upheld by identity theory, and with posits about social influence explored in the previous chapter. Such examination and correlation will be supported by the following paradigms or models for identity construction and social influence. These paradigms have been reiterated in the works of several scholars who posit within the realm of cultural and social identity: • Socialization processes; • The notion of social text; • Positioning through performer and audience relationships; • Cultural practice and performance as part of ritual; and • Globalization. Processes of Socialization Empirical evidence to support claims that calypso music has contributed to social change may well be generated from historical accounts and from the fact that the structuralist proposition that “performance simply reflects ‘underlying’ cultural patterns and social structures is no longer plausible among ethnomusicologists and anthropologists” (Stokes, 1994, p. -

Jamaican Dancehall in the 21St Century

Pon de Dancefloor: Jamaican Dancehall in the 21st Century Stephanie R. Espie University of Delaware [email protected] Abstract The history of Jamaican music includes Roots, Mento, Ska, Rocksteady and Reggae styles - setting the stage for the origination of the Dancehall genre in the early 1980s. While a wide range of ethnographic literature has been published on these musical foundations, few publications exist on the evolution of Dancehall in Jamaica. Dancehall has expanded in the past 10-15 years due to increasing effects of collaboration between American and Jamaican artists and DJs along with the ease of musical transmission through technology. In this ethnographic research, I have studied the evolution of Dancehall to create a portrayal of musical trends leading to the predominance of Dancehall in Jamaica. I collected data over 10 days of fieldwork in Portland, Jamaica in June of 2015. The music played by four club DJs was chosen as the focus of study because of its influence on Portland’s musical culture. Data consisted of observational field notes and 10 hours of audio recordings of local DJs in club settings. Audio recordings were analyzed for traditional beats, song length, production year, language choice, and added effects. Field notes were used as a secondary source to confirm/disconfirm the emerging musical themes from across these DJs. Findings have been compared to the existing literature to create an updated trajectory of musical trends within Dancehall. Along with contributions to the field of ethnomusicology, this research can be used in music education in informal music learning on a domestic and international level.