Birding June 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica Photo Journey: July 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica Photo Journey: July 2017 Costa Rica Photo Journey 16-25 July 2017 Tour Leader: Jay Packer Many thanks to Deepak Ramineedi for allowing us to include his photos in this trip report. This Yellow-throated Toucan at Laguna del Lagarto wasn’t bothered at all by the rain. Note: Except where noted otherwise, all photos in this trip report were taken by Jay Packer. www.tropicalbirding.com +1- 409-515-9110 [email protected] Page 1 Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica Photo Journey: July 2017 Introduction This Costa Rican photo journey featured visits to five regions of this small Central American country. We covered the moist Caribbean slope, Caribbean lowlands, dry forests on the Pacific slope, a large tropical river, and cloud forests of the volcanic highlands. The clients on the tour were a young couple and their 8-month old son. Given the considerations of traveling with an infant, the pace of the tour was relaxed and much of the photography was done at feeders or from the car. Even so, the diversity of Costa Rica was impressive as we encountered almost 200 species, photographing most of the targets that we hoped to see. Photographic highlights of the trip included stunning shots of toucan species in the rain, great hummingbird multiflash photography, a nesting pair of Turquoise-browed Motmots, Spectacled Owl, King Vultures, Resplendent Quetzal, very cooperative Great Green and Scarlet Macaws, Costa Rican Pygmy-Owl, and more. 16 July 2017 We began the tour with a drive out of San Jose to the well known Casa de Cope, west of Guápiles. -

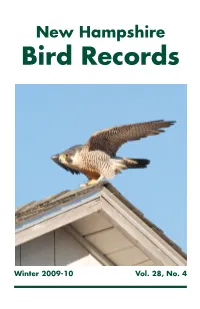

NH Bird Records

V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Winter 2009-10 Vol. 28, No. 4 V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page ii AUDUBON SOCIETY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 28, Number 4 Winter 2009-10 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Text Editor: Dan Hubbard Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; Tony Vazzano, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Assistants: Jeannine Ayer, Lynn Edwards, Margot Johnson, Susan MacLeod, Marie Nickerson, Carol Plato, William Taffe, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano Photo Quiz: David Donsker Photo Editor: Jon Woolf Web Master: Len Medlock Editorial Team: Phil Brown, Hank Chary, David Deifik, David Donsker, Dan Hubbard, Pam Hunt, Iain MacLeod, Len Medlock, Stephen Mirick, Robert Quinn, Rebecca Suomala, William Taffe, Lance Tanino, Tony Vazzano, Jon Woolf Cover Photo: Peregrine Falcon by Jon Woolf, 12/1/09, Hampton Beach State Park, Hampton, NH. New Hampshire Bird Records is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department. Bird sight- ings are submitted to NH eBird (www.ebird.org/nh) by many different observers. Records are selected for publication and not all species reported will appear in the issue. The published sightings typically represent the highlights of the season. All records are subject to review by the NH Rare Birds Committee and publication of reports here does not imply future acceptance by the Committee. Please contact the Managing Editor if you would like to report your sightings but are unable to use NH eBird. -

January 2020.Indd

BROWN PELICAN Photo by Rob Swindell at Melbourne, Florida JANUARY 2020 Editors: Jim Jablonski, Marty Ackermann, Tammy Martin, Cathy Priebe Webmistress: Arlene Lengyel January 2020 Program Tuesday, January 7, 2020, 7 p.m. Carlisle Reservation Visitor Center Gulls 101 Chuck Slusarczyk, Jr. "I'm happy to be presenting my program Gulls 101 to the good people of Black River Audubon. Gulls are notoriously difficult to identify, but I hope to at least get you looking at them a little closer. Even though I know a bit about them, I'm far from an expert in the field and there is always more to learn. The challenge is to know the particular field marks that are most important, and familiarization with the many plumage cycles helps a lot too. No one will come out of this presentation an expert, but I hope that I can at least give you an idea what to look for. At the very least, I hope you enjoy the photos. Looking forward to seeing everyone there!” Chuck Slusarczyk is an avid member of the Ohio birding community, and his efforts to assist and educate novice birders via social media are well known, yet he is the first to admit that one never stops learning. He has presented a number of programs to Black River Audubon, always drawing a large, appreciative gathering. 2019 Wellington Area Christmas Bird Count The Wellington-area CBC will take place Saturday, December 28, 2019. Meet at the McDonald’s on Rt. 58 at 8:00 a.m. The leader is Paul Sherwood. -

Bird List Column A: 1 = 70-90% Chance Column B: 2 = 30-70% Chance Column C: 3 = 10-30% Chance

Colombia: Chocó Prospective Bird List Column A: 1 = 70-90% chance Column B: 2 = 30-70% chance Column C: 3 = 10-30% chance A B C Tawny-breasted Tinamou 2 Nothocercus julius Highland Tinamou 3 Nothocercus bonapartei Great Tinamou 2 Tinamus major Berlepsch's Tinamou 3 Crypturellus berlepschi Little Tinamou 1 Crypturellus soui Choco Tinamou 3 Crypturellus kerriae Horned Screamer 2 Anhima cornuta Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 1 Dendrocygna autumnalis Fulvous Whistling-Duck 1 Dendrocygna bicolor Comb Duck 3 Sarkidiornis melanotos Muscovy Duck 3 Cairina moschata Torrent Duck 3 Merganetta armata Blue-winged Teal 3 Spatula discors Cinnamon Teal 2 Spatula cyanoptera Masked Duck 3 Nomonyx dominicus Gray-headed Chachalaca 1 Ortalis cinereiceps Colombian Chachalaca 1 Ortalis columbiana Baudo Guan 2 Penelope ortoni Crested Guan 3 Penelope purpurascens Cauca Guan 2 Penelope perspicax Wattled Guan 2 Aburria aburri Sickle-winged Guan 1 Chamaepetes goudotii Great Curassow 3 Crax rubra Tawny-faced Quail 3 Rhynchortyx cinctus Crested Bobwhite 2 Colinus cristatus Rufous-fronted Wood-Quail 2 Odontophorus erythrops Chestnut Wood-Quail 1 Odontophorus hyperythrus Least Grebe 2 Tachybaptus dominicus Pied-billed Grebe 1 Podilymbus podiceps Magnificent Frigatebird 1 Fregata magnificens Brown Booby 2 Sula leucogaster ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com (866) 547 9868 Toll free US + Canada ● Tel (520) 320-9868 ● Fax (520) -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

i procp:edings of uxited states national :\[uset7m. 359 23498 g. D. 13 5 A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; 0. 31 ; B. S. Leiigtli ICT millime- ters. GGGl. 17 specimeus. St. Michaels, Alaslai. II. M. Bannister. a. Length 210 millimeters. D. 13; A. 14; V. 3; P. 33; C— ; B. 8. h. Length 200 millimeters. D. 14: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C— ; B. 8. e. Length 135 millimeters. D. 12: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C. 30; B. 8. The remaining fourteen specimens vary in length from 110 to 180 mil- limeters. United States National Museum, WasJiingtoiij January 5, 1880. FOURTBI III\.STAI.:HEIVT OF ©R!VBTBIOI.O«ICAI. BIBI.IOCiRAPHV r BE:INC} a Jf.ffJ^T ©F FAUIVA!. I»l.TjBf.S«'ATI©.\S REff,ATIIV« T© BRIT- I!§H RIRD!^. My BR. ELS^IOTT COUES, U. S. A. The zlppendix to the "Birds of the Colorado Yalley- (pp. 507 [lJ-784 [218]), which gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to North American Birds, is to be considered as the first instalment of a "Uni- versal Bibliography of Ornithology''. The second instalment occupies pp. 230-330 of the " Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories 'V Yol. Y, No. 2, Sept. G, 1879, and similarly gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to the Birds of the rest of America.. The.third instalment, which occnpies the same "Bulletin", same Yol.,, No. 4 (in press), consists of an entirely different set of titles, being those belonging to the "systematic" department of the whole Bibliography^ in so far as America is concerned. -

Hungary & Transylvania

Although we had many exciting birds, the ‘Bird of the trip’ was Wallcreeper in 2015. (János Oláh) HUNGARY & TRANSYLVANIA 14 – 23 MAY 2015 LEADER: JÁNOS OLÁH Central and Eastern Europe has a great variety of bird species including lots of special ones but at the same time also offers a fantastic variety of different habitats and scenery as well as the long and exciting history of the area. Birdquest has operated tours to Hungary since 1991, being one of the few pioneers to enter the eastern block. The tour itinerary has been changed a few times but nowadays the combination of Hungary and Transylvania seems to be a settled and well established one and offers an amazing list of European birds. This tour is a very good introduction to birders visiting Europe for the first time but also offers some difficult-to-see birds for those who birded the continent before. We had several tour highlights on this recent tour but certainly the displaying Great Bustards, a majestic pair of Eastern Imperial Eagle, the mighty Saker, the handsome Red-footed Falcon, a hunting Peregrine, the shy Capercaillie, the elusive Little Crake and Corncrake, the enigmatic Ural Owl, the declining White-backed Woodpecker, the skulking River and Barred Warblers, a rare Sombre Tit, which was a write-in, the fluty Red-breasted and Collared Flycatchers and the stunning Wallcreeper will be long remembered. We recorded a total of 214 species on this short tour, which is a respectable tally for Europe. Amongst these we had 18 species of raptors, 6 species of owls, 9 species of woodpeckers and 15 species of warblers seen! Our mammal highlight was undoubtedly the superb views of Carpathian Brown Bears of which we saw ten on a single afternoon! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Hungary & Transylvania 2015 www.birdquest-tours.com We also had a nice overview of the different habitats of a Carpathian transect from the Great Hungarian Plain through the deciduous woodlands of the Carpathian foothills to the higher conifer-covered mountains. -

N° English Name Scientific Name Status Day 1

1 FUNDACIÓN JOCOTOCO CHECK-LIST OF THE BIRDS OF YANACOCHA N° English Name Scientific Name Status Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 1 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius R 2 Curve-billed Tinamou Nothoprocta curvirostris U 3 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata 4 Andean Teal Anas andium 5 Andean Guan Penelope montagnii U 6 Sickle-winged Guan Chamaepetes goudotii 7 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 8 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus 9 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 10 Andean Condor Vultur gryphus R Sharp-shinned Hawk (Plain- 11 breasted Hawk) Accipiter striatus U 12 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus 13 Black-and-chestnut Eagle Spizaetus isidori 14 Cinereous Harrier Circus cinereus 15 Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris 16 White-rumped Hawk Parabuteo leucorrhous 17 Black-chested Buzzard-Eagle Geranoaetus melanoleucus U 18 White-throated Hawk Buteo albigula R 19 Variable Hawk Geranoaetus polyosoma U 20 Andean Lapwing Vanellus resplendens VR 21 Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe Attagis gayi 22 Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda R 23 Baird's Sandpiper Calidris bairdii VR 24 Andean Snipe Gallinago jamesoni FC 25 Imperial Snipe Gallinago imperialis U 26 Noble Snipe Gallinago nobilis 27 Jameson's Snipe Gallinago jamesoni 28 Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius 29 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagoienas fasciata FC 30 Plumbeous Pigeon Patagioenas plumbea 31 Common Ground-Dove Columbina passerina 32 White-tipped Dove Leptotila verreauxi R 33 White-throated Quail-Dove Zentrygon frenata U 34 Eared Dove Zenaida auriculata U 35 Barn Owl Tyto alba 36 White-throated Screech-Owl Megascops -

Checklistccamp2016.Pdf

2 3 Participant’s Name: Tour Company: Date#1: / / Tour locations Date #2: / / Tour locations Date #3: / / Tour locations Date #4: / / Tour locations Date #5: / / Tour locations Date #6: / / Tour locations Date #7: / / Tour locations Date #8: / / Tour locations Codes used in Column A Codes Sample Species a = Abundant Red-lored Parrot c = Common White-headed Wren u = Uncommon Gray-cheeked Nunlet r = Rare Sapayoa vr = Very rare Wing-banded Antbird m = Migrant Bay-breasted Warbler x = Accidental Dwarf Cuckoo (E) = Endemic Stripe-cheeked Woodpecker Species marked with an asterisk (*) can be found in the birding areas visited on the tour outside of the immediate Canopy Camp property such as Nusagandi, San Francisco Reserve, El Real and Darien National Park/Cerro Pirre. Of course, 4with incredible biodiversity and changing environments, there is always the possibility to see species not listed here. If you have a sighting not on this list, please let us know! No. Bird Species 1A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tinamous Great Tinamou u 1 Tinamus major Little Tinamou c 2 Crypturellus soui Ducks Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 3 Dendrocygna autumnalis u Muscovy Duck 4 Cairina moschata r Blue-winged Teal 5 Anas discors m Curassows, Guans & Chachalacas Gray-headed Chachalaca 6 Ortalis cinereiceps c Crested Guan 7 Penelope purpurascens u Great Curassow 8 Crax rubra r New World Quails Tawny-faced Quail 9 Rhynchortyx cinctus r* Marbled Wood-Quail 10 Odontophorus gujanensis r* Black-eared Wood-Quail 11 Odontophorus melanotis u Grebes Least Grebe 12 Tachybaptus dominicus u www.canopytower.com 3 BirdChecklist No. -

Birding Madagascar 1-22 November 2018

Birding Madagascar 1-22 November 2018. Trip report compiled by Tomas Carlberg. 1 Front cover Daily log Red-capped Coua, sunbathing in Ankarafantsika National Park. Photo: Tomas Carlberg November 1st Some of us (TC, JN, and RN) flew Air France from Photos Arlanda, Stockholm at 06:00 to Paris, where we © All photos in this report: Tomas Carlberg. met OP (who flew from Gothenburg) and IF (flew For additional photos, see p. 30 ff. from Manchester). An 11 hrs flight took us to Antananarivo, where we landed just before Participants midnight. Once through after visa and passport control we met Zina at the airport. We stayed at IC Tomas Carlberg (Tour leader), Jonas Nordin, Hotel and fell asleep at 01:30. Sweden; Rolf Nordin, Sweden; Olof Persson, Sweden; Jesper Hornskov, Denmark; Eric November 2nd Schaumburg, Denmark; Hans Harrestrup Andersen, Woke up at 6, met the Danes (JH, ES, HW, and Denmark; Hans Wulffsberg, Denmark; Ian Fryer, UK HHA), and had breakfast. Changed c. 400 Euro each Serge “Zina” Raheritsiferana (organizer and driver), and got 1 540 000 ariary… Departure at 7:30 Fidson “Fidy” Albert Alberto (guide), and Lala. heading north towards Ankarafantsika NP. Saw a male Malagasy Harrier c. 16 km south of Ankazobe Correspondence (-18.45915, 47.160156), so stopped for birding [email protected] (Tomas Carlberg) there 9:45-10:05. Stop at 11:40 to buy sandwiches for lunch. Lunch with birding 12:55-13:15. Long Tour organizers transport today… Stopped for birding at bridge Serge “Zina” Raheritsiferana (Zina-Go Travel), over Betsiboka River 16:30-17:30; highlight here Stig Holmstedt. -

Trip Report February 12 – 21, 2020 | Written by Dodie Logue

Southern Belize: Pristine & Wild | Trip Report February 12 – 21, 2020 | Written by Dodie Logue With Guide Dodie Logue, and participants Dennis, Helen, Kay, Hayden, Judy, Tony, Christine, Larry, Carol, Jamie, Ellen, Naturalist Journeys, LLC | Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 | 866.900.1146 Fax 650.471.7667 naturalistjourneys.com | caligo.com [email protected] | [email protected] Wed., Feb. 12 Early arrivals | Transfer to Crooked Tree | Pre-extension Today most of the group arrived; some had come in a day or two earlier on their own. There were airport shuttles and getting situated in the two lodges, Crooked Tree and Beck’s, which were just over a mile apart. Some of the earlier arrivals had a little time to bird the grounds of their lodge. Crooked Tree Village is a small area, NW of Belize City, about 45 minutes by car. The residents rely on tourism, as well as fishing and farming, for their livelihood. Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary was established in 1984 and is run by Audubon. It encompasses around 25 square miles of government-sanctioned land, including freshwater lagoons, savannah, and broadleaf and pine woods. Some of the birds seen right on the grounds for the early arrivals were Black- cowled Oriole, Red-lored Parrot, and Lineated Woodpecker. There were two airport shuttles to pick up the various arrivals, and at 6:30 PM we all met as a group in the dining room at Beck’s for a meal of coconut curry fish, herbed chicken, and rice and beans. Hearty and delicious! Most were tired from a long travel day and, knowing about the early departure the next morning, we all went off to our lodges and were soon tucked in. -

ON 1196 NEW.Fm

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 25: 237–243, 2014 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society NON-RANDOM ORIENTATION IN WOODPECKER CAVITY ENTRANCES IN A TROPICAL RAIN FOREST Daniel Rico1 & Luis Sandoval2,3 1The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska. 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Windsor, 401 Sunset Avenue, Windsor, ON, Canada, N9B3P4. 3Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, San José, Costa Rica, CP 2090. E-mail: [email protected] Orientación no al azar de las entradas de las cavidades de carpinteros en un bosque tropical. Key words: Pale-billed Woodpecker, Campephilus guatemalensis, Chestnut-colored Woodpecker, Celeus castaneus, Lineated Woodpecker, Dryocopus lineatus, Black-cheeked Woodpecker, Melanerpes pucherani, Costa Rica, Picidae. INTRODUCTION tics such as vegetation coverage of the nesting substrate, surrounding vegetation, and forest Nest site selection play’s one of the main roles age (Aitken et al. 2002, Adkins Giese & Cuth- in the breeding success of birds, because this bert 2003, Sandoval & Barrantes 2006). Nest selection influences the survival of eggs, orientation also plays an important role in the chicks, and adults by inducing variables such breeding success of woodpeckers, because the as the microclimatic conditions of the nest orientation positively influences the microcli- and probability of being detected by preda- mate conditions inside the nest cavity (Hooge tors (Viñuela & Sunyer 1992). Although et al. 1999, Wiebe 2001), by reducing the woodpecker nest site selections are well estab- exposure to direct wind currents, rainfalls, lished, the majority of this information is and/or extreme temperatures (Ardia et al. based on temperate forest species and com- 2006). Cavity entrance orientation showed munities (Newton 1998, Cornelius et al. -

Mexico Chiapas 15Th April to 27Th April 2021 (13 Days)

Mexico Chiapas 15th April to 27th April 2021 (13 days) Horned Guan by Adam Riley Chiapas is the southernmost state of Mexico, located on the border of Guatemala. Our 13 day tour of Chiapas takes in the very best of the areas birding sites such as San Cristobal de las Casas, Comitan, the Sumidero Canyon, Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Tapachula and Volcan Tacana. A myriad of beautiful and sought after species includes the amazing Giant Wren, localized Nava’s Wren, dainty Pink-headed Warbler, Rufous-collared Thrush, Garnet-throated and Amethyst-throated Hummingbird, Rufous-browed Wren, Blue-and-white Mockingbird, Bearded Screech Owl, Slender Sheartail, Belted Flycatcher, Red-breasted Chat, Bar-winged Oriole, Lesser Ground Cuckoo, Lesser Roadrunner, Cabanis’s Wren, Mayan Antthrush, Orange-breasted and Rose-bellied Bunting, West Mexican Chachalaca, Citreoline Trogon, Yellow-eyed Junco, Unspotted Saw-whet Owl and Long- tailed Sabrewing. Without doubt, the tour highlight is liable to be the incredible Horned Guan. While searching for this incomparable species, we can expect to come across a host of other highlights such as Emerald-chinned, Wine-throated and Azure-crowned Hummingbird, Cabanis’s Tanager and at night the haunting Fulvous Owl! RBL Mexico – Chiapas Itinerary 2 THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Tuxtla Gutierrez, transfer to San Cristobal del las Casas Day 2 San Cristobal to Comitan Day 3 Comitan to Tuxtla Gutierrez Days 4, 5 & 6 Sumidero Canyon and Eastern Sierra tropical forests Day 7 Arriaga to Mapastepec via the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Day 8 Mapastepec to Tapachula Day 9 Benito Juarez el Plan to Chiquihuites Day 10 Chiquihuites to Volcan Tacana high camp & Horned Guan Day 11 Volcan Tacana high camp to Union Juarez Day 12 Union Juarez to Tapachula Day 13 Final departures from Tapachula TOUR MAP… RBL Mexico – Chiapas Itinerary 3 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1: Arrival in Tuxtla Gutierrez, transfer to San Cristobal del las Casas.