Automatic Library Tracking Database

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design and Implementation of Generics for the .NET Common Language Runtime

Design and Implementation of Generics for the .NET Common Language Runtime Andrew Kennedy Don Syme Microsoft Research, Cambridge, U.K. fakeÒÒ¸d×ÝÑeg@ÑicÖÓ×ÓfغcÓÑ Abstract cally through an interface definition language, or IDL) that is nec- essary for language interoperation. The Microsoft .NET Common Language Runtime provides a This paper describes the design and implementation of support shared type system, intermediate language and dynamic execution for parametric polymorphism in the CLR. In its initial release, the environment for the implementation and inter-operation of multiple CLR has no support for polymorphism, an omission shared by the source languages. In this paper we extend it with direct support for JVM. Of course, it is always possible to “compile away” polymor- parametric polymorphism (also known as generics), describing the phism by translation, as has been demonstrated in a number of ex- design through examples written in an extended version of the C# tensions to Java [14, 4, 6, 13, 2, 16] that require no change to the programming language, and explaining aspects of implementation JVM, and in compilers for polymorphic languages that target the by reference to a prototype extension to the runtime. JVM or CLR (MLj [3], Haskell, Eiffel, Mercury). However, such Our design is very expressive, supporting parameterized types, systems inevitably suffer drawbacks of some kind, whether through polymorphic static, instance and virtual methods, “F-bounded” source language restrictions (disallowing primitive type instanti- type parameters, instantiation at pointer and value types, polymor- ations to enable a simple erasure-based translation, as in GJ and phic recursion, and exact run-time types. -

Architectural Support for Dynamic Linking Varun Agrawal, Abhiroop Dabral, Tapti Palit, Yongming Shen, Michael Ferdman COMPAS Stony Brook University

Architectural Support for Dynamic Linking Varun Agrawal, Abhiroop Dabral, Tapti Palit, Yongming Shen, Michael Ferdman COMPAS Stony Brook University Abstract 1 Introduction All software in use today relies on libraries, including All computer programs in use today rely on software standard libraries (e.g., C, C++) and application-specific libraries. Libraries can be linked dynamically, deferring libraries (e.g., libxml, libpng). Most libraries are loaded in much of the linking process to the launch of the program. memory and dynamically linked when programs are Dynamically linked libraries offer numerous benefits over launched, resolving symbol addresses across the applica- static linking: they allow code reuse between applications, tions and libraries. Dynamic linking has many benefits: It conserve memory (because only one copy of a library is kept allows code to be reused between applications, conserves in memory for all applications that share it), allow libraries memory (because only one copy of a library is kept in mem- to be patched and updated without modifying programs, ory for all the applications that share it), and allows enable effective address space layout randomization for libraries to be patched and updated without modifying pro- security [21], and many others. As a result, dynamic linking grams, among numerous other benefits. However, these is the predominant choice in all systems today [7]. benefits come at the cost of performance. For every call To facilitate dynamic linking of libraries, compiled pro- made to a function in a dynamically linked library, a trampo- grams include function call trampolines in their binaries. line is used to read the function address from a lookup table When a program is launched, the dynamic linker maps the and branch to the function, incurring memory load and libraries into the process address space and resolves external branch operations. -

CS429: Computer Organization and Architecture Linking I & II

CS429: Computer Organization and Architecture Linking I & II Dr. Bill Young Department of Computer Sciences University of Texas at Austin Last updated: April 5, 2018 at 09:23 CS429 Slideset 23: 1 Linking I A Simplistic Translation Scheme m.c ASCII source file Problems: Efficiency: small change Compiler requires complete re-compilation. m.s Modularity: hard to share common functions (e.g., printf). Assembler Solution: Static linker (or Binary executable object file linker). p (memory image on disk) CS429 Slideset 23: 2 Linking I Better Scheme Using a Linker Linking is the process of m.c a.c ASCII source files combining various pieces of code and data into a Compiler Compiler single file that can be loaded (copied) into m.s a.s memory and executed. Linking could happen at: Assembler Assembler compile time; Separately compiled m.o a.o load time; relocatable object files run time. Linker (ld) Must somehow tell a Executable object file module about symbols p (code and data for all functions defined in m.c and a.c) from other modules. CS429 Slideset 23: 3 Linking I Linking A linker takes representations of separate program modules and combines them into a single executable. This involves two primary steps: 1 Symbol resolution: associate each symbol reference throughout the set of modules with a single symbol definition. 2 Relocation: associate a memory location with each symbol definition, and modify each reference to point to that location. CS429 Slideset 23: 4 Linking I Translating the Example Program A compiler driver coordinates all steps in the translation and linking process. -

Tricore Architecture Manual for a Detailed Discussion of Instruction Set Encoding and Semantics

User’s Manual, v2.3, Feb. 2007 TriCore 32-bit Unified Processor Core Embedded Applications Binary Interface (EABI) Microcontrollers Edition 2007-02 Published by Infineon Technologies AG 81726 München, Germany © Infineon Technologies AG 2007. All Rights Reserved. Legal Disclaimer The information given in this document shall in no event be regarded as a guarantee of conditions or characteristics (“Beschaffenheitsgarantie”). With respect to any examples or hints given herein, any typical values stated herein and/or any information regarding the application of the device, Infineon Technologies hereby disclaims any and all warranties and liabilities of any kind, including without limitation warranties of non- infringement of intellectual property rights of any third party. Information For further information on technology, delivery terms and conditions and prices please contact your nearest Infineon Technologies Office (www.infineon.com). Warnings Due to technical requirements components may contain dangerous substances. For information on the types in question please contact your nearest Infineon Technologies Office. Infineon Technologies Components may only be used in life-support devices or systems with the express written approval of Infineon Technologies, if a failure of such components can reasonably be expected to cause the failure of that life-support device or system, or to affect the safety or effectiveness of that device or system. Life support devices or systems are intended to be implanted in the human body, or to support and/or maintain and sustain and/or protect human life. If they fail, it is reasonable to assume that the health of the user or other persons may be endangered. User’s Manual, v2.3, Feb. -

Protecting Against Unexpected System Calls

Protecting Against Unexpected System Calls C. M. Linn, M. Rajagopalan, S. Baker, C. Collberg, S. K. Debray, J. H. Hartman Department of Computer Science University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721 {linnc,mohan,bakers,collberg,debray,jhh}@cs.arizona.edu Abstract writing the return address on the stack with the address of the attack code). This then causes the various actions This paper proposes a comprehensive set of techniques relating to the attack to be carried out. which limit the scope of remote code injection attacks. These techniques prevent any injected code from mak- In order to do any real damage, e.g., create a root ing system calls and thus restrict the capabilities of an shell, change permissions on a file, or access proscribed attacker. In defending against the traditional ways of data, the attack code needs to execute one or more sys- harming a system these techniques significantly raise the tem calls. Because of this, and the well-defined system bar for compromising the host system forcing the attack call interface between application code and the underly- code to take extraordinary steps that may be impractical ing operating system kernel, many researchers have fo- in the context of a remote code injection attack. There cused on the system call interface as a convenient point are two main aspects to our approach. The first is to for detecting and disrupting such attacks (see, for exam- embed semantic information into executables identify- ple, [5, 13, 17, 19, 29, 32, 35, 38]; Section 7 gives a more ing the locations of legitimate system call instructions; extensive discussion). -

Cray XT Programming Environment's Implementation of Dynamic Shared Libraries

Cray XT Programming Environment’s Implementation of Dynamic Shared Libraries Geir Johansen, Cray Inc. Barb Mauzy, Cray Inc. ABSTRACT: The Cray XT Programming Environment will support the implementation of dynamic shared libraries in future Cray XT CLE releases. The Cray XT implementation will provide the flexibility to allow specific library versions to be chosen at both link and run times. The implementation of dynamic shared libraries allows dynamically linked executables built with software other than the Cray Programming Environment to be run on the Cray XT. KEYWORDS: Cray XT, Programming Environment CUG 2009 Proceedings 1 of 10 information in physical memory that can be shared among 1.0 Introduction multiple processes. This feature potentially reduces the memory allocated for a program on a compute node. This The goal of this paper is provide application analysts advantage becomes more important as the number of a description of Cray XT Programming Environment‟s available cores increases. implementation of dynamic shared libraries. Topics Another advantage of dynamically linked executables covered include the building of dynamic shared library is that the system libraries can be upgraded and take effect programs, configuring the version of dynamic shared without the need to relink applications. The ability to libraries to be used at execution time, and the execution of install library changes without having to rebuild a program a dynamically linked program not built with the Cray XT is a significant advantage in quickly addressing problems, Programming Environment. While a brief description of such as a security issue with a library code. The the Cray XT system implementation of dynamic shared experiences of system administrators have shown that libraries will be given, the Cray XT system architecture codes using dynamic shared libraries are more resilient to and system administration issues of dynamic shared system upgrades than codes using static libraries [1]. -

Tribits Lifecycle Model Version

SANDIA REPORT SAND2012-0561 Unlimited Release Printed February 2012 TriBITS Lifecycle Model Version 1.0 A Lean/Agile Software Lifecycle Model for Research-based Computational Science and Engineering and Applied Mathematical Software Roscoe A. Bartlett Michael A. Heroux James M. Willenbring Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia National Laboratories is a multi-program laboratory managed and operated by Sandia Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lockheed Martin Corporation, for the U.S. Department of Energys National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or rep- resent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. -

Dynamic Linking Considered Harmful

DYNAMIC LINKING CONSIDERED HARMFUL 1 WHY WE NEED LINKING ¡ Want to access code/data defined somewhere else (another file in our project, a library, etc) ¡ In compiler-speak, “we want symbols with external linkage” § I only really care about functions here ¡ Need a mechanism by which we can reference symbols whose location we don’t know ¡ A linker solves this problem. Takes symbols annotated by the compiler (unresolved symbols) and patches them 2 DYNAMIC LINKING ¡ We want to: ¡ use code defined somewhere else, but we don’t want to have to recompile/link when it’s updated ¡ be able to link only those symbols used as runtime (deferred/lazy linking) ¡ be more efficient with resources (may get to this later) 3 CAVEATS ¡ Applies to UNIX, particularly Linux, x86 architecture, ELF Relevant files: -glibcX.X/elf/rtld.c -linux-X.X.X/fs/exec.c, binfmt_elf.c -/usr/include/linux/elf.h ¡ (I think) Windows linking operates similarly 4 THE BIRTH OF A PROCESS 5 THE COMPILER ¡ Compiles your code into a relocatable object file (in the ELF format, which we’ll get to see more of later) ¡ One of the chunks in the .o is a symbol table ¡ This table contains the names of symbols referenced and defined in the file ¡ Unresolved symbols will have relocation entries (in a relocation table) 6 THE LINKER ¡ Patches up the unresolved symbols it can. If we’re linking statically, it has to fix all of them. Otherwise, at runtime ¡ Relocation stage. Will not go into detail here. § Basically, prepares program segments and symbol references for load time 7 THE SHELL fork(), exec() 8 THE KERNEL (LOADER) ¡ Loaders are typically kernel modules. -

Lecture 2 — Software Correctness

Lecture 2 — Software Correctness David J. Pearce School of Engineering and Computer Science Victoria University of Wellington Software Correctness RECOMMENDATIONS To Builders and Users of Software Make the most of effective software development technologies and formal methods. A variety of modern technologies — in particular, safe programming languages, static analysis, and formal methods — are likely to reduce the cost and difficulty of producing dependable software. Elementary best practices, such as source code control and systematic defect tracking, should be universally adopted, . –Software for Dependable Systems Patriot Missle 1991, Dhahran - Iraqi Scud missile hits barracks killing 28 soldiers - Patriot system was activated, but missed target by over 600m - Floating point representation of 0.1 was cause (rounding error over time, required 100 hours of continuous operation) See: “Engineering Disasters” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EMVBLg2MrLs (Image by Darkone - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5) Unintended Acceleration? (Overview) Braking Problems (Toyota Prius) Drivers reported “sudden acceleration” when braking By 2010, over seven million cars recalled NASA experts called into investigate Specialists in static analysis Their report had significant redactions though Bookout vs Toyota, 2013 Victim’s awarded $1.5million each Barr provided expert testimony See “Unintended Acceleration and Other Embedded Software bugs”, Michael Barr, 2011 See “An Update on Toyota and Unintended acceleration” Unintended Acceleration? (NASA Analysis) Throttle -

Linker Script Guide Emprog

Linker Script Guide Emprog Emprog ThunderBench™ Linker Script Guide Version 1.2 ©May 2013 Page | 1 Linker Script Guide Emprog 1 - Linker Script guide 2 -Arm Specific Options Page | 2 Linker Script Guide Emprog 1 The Linker Scripts Every link is controlled by a linker script. This script is written in the linker command language. The main purpose of the linker script is to describe how the sections in the input files should be mapped into the output file, and to control the memory layout of the output file. Most linker scripts do nothing more than this. However, when necessary, the linker script can also direct the linker to perform many other operations, using the commands described below. The linker always uses a linker script. If you do not supply one yourself, the linker will use a default script that is compiled into the linker executable. You can use the ‘--verbose’ command line option to display the default linker script. Certain command line options, such as ‘-r’ or ‘-N’, will affect the default linker script. You may supply your own linker script by using the ‘-T’ command line option. When you do this, your linker script will replace the default linker script. You may also use linker scripts implicitly by naming them as input files to the linker, as though they were files to be linked. 1.1 Basic Linker Script Concepts We need to define some basic concepts and vocabulary in order to describe the linker script language. The linker combines input files into a single output file. The output file and each input file are in a special data format known as an object file format. -

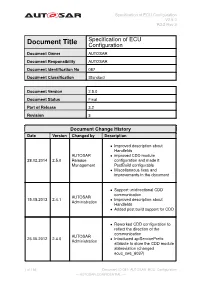

Configuration Description (And the Resulting ECU Ex- Tract of the System Configuration for the Individual Ecus)

Specification of ECU Configuration V2.5.0 R3.2 Rev 3 Specification of ECU Document Title Configuration Document Owner AUTOSAR Document Responsibility AUTOSAR Document Identification No 087 Document Classification Standard Document Version 2.5.0 Document Status Final Part of Release 3.2 Revision 3 Document Change History Date Version Changed by Description • Improved description about HandleIds AUTOSAR • improved CDD module 28.02.2014 2.5.0 Release configuration and made it Management PostBuild configurable • Miscellaneous fixes and improvements in the document • Support unidirectional CDD communication AUTOSAR 15.05.2013 2.4.1 • Improved description about Administration HandleIds • Added post build support for CDD • Reworked CDD configuration to reflect the direction of the communication AUTOSAR 25.05.2012 2.4.0 • Introduced apiServicePrefix Administration attribute to store the CDD module abbreviation (changed ecuc_sws_6037) 1 of 156 Document ID 087: AUTOSAR_ECU_Configuration — AUTOSAR CONFIDENTIAL — Specification of ECU Configuration V2.5.0 R3.2 Rev 3 • Added section on Complex Device Driver (section 4.4) • Clarification of PostBuildSelectable, PostBuildLoadable in VSMD AUTOSAR 31.03.2011 2.3.0 (added ecuc_sws_6046, Administration ecuc_sws_6047, ecuc_sws_6048, ecuc_sws_6049) • set configuration class affection support to deprecated AUTOSAR Updated definition how symbolic 14.10.2009 2.2.0 Administration names are generated from the EcuC. AUTOSAR Fixed foreign reference to 15.09.2008 2.1.0 Administration PduToFrameMapping AUTOSAR 01.07.2008 2.0.2 Legal -

Sta C Linking

Carnegie Mellon Linking 15-213: Introduc;on to Computer Systems 13th Lecture, Oct. 13, 2015 Instructors: Randal E. Bryant and David R. O’Hallaron Bryant and O’Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspec;ve, Third Edi;on 1 Carnegie Mellon Today ¢ Linking ¢ Case study: Library interposioning Bryant and O’Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspec;ve, Third Edi;on 2 Carnegie Mellon Example C Program int sum(int *a, int n);! int sum(int *a, int n)! ! {! int array[2] = {1, 2};! int i, s = 0;! ! ! int main()! for (i = 0; i < n; i++) {! {! s += a[i];! int val = sum(array, 2);! }! return val;! return s;! }! }! main.c ! sum.c Bryant and O’Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspec;ve, Third Edi;on 3 Carnegie Mellon Sta7c Linking ¢ Programs are translated and linked using a compiler driver: § linux> gcc -Og -o prog main.c sum.c § linux> ./prog main.c sum.c Source files Translators Translators (cpp, cc1, as) (cpp, cc1, as) main.o sum.o Separately compiled relocatable object files Linker (ld) Fully linked executable object file prog (contains code and data for all func;ons defined in main.c and sum.c) Bryant and O’Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspec;ve, Third Edi;on 4 Carnegie Mellon Why Linkers? ¢ Reason 1: Modularity § Program can be wriNen as a collec;on of smaller source files, rather than one monolithic mass. § Can build libraries of common func;ons (more on this later) § e.g., Math library, standard C library Bryant and O’Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspec;ve, Third Edi;on 5 Carnegie Mellon Why Linkers? (cont) ¢ Reason 2: Efficiency § Time: Separate compilaon § Change one source file, compile, and then relink.