The Revelation· Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review and Updated Checklist of Freshwater Fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, Distribution and Conservation Status

Iran. J. Ichthyol. (March 2017), 4(Suppl. 1): 1–114 Received: October 18, 2016 © 2017 Iranian Society of Ichthyology Accepted: February 30, 2017 P-ISSN: 2383-1561; E-ISSN: 2383-0964 doi: 10.7508/iji.2017 http://www.ijichthyol.org Review and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, distribution and conservation status Hamid Reza ESMAEILI1*, Hamidreza MEHRABAN1, Keivan ABBASI2, Yazdan KEIVANY3, Brian W. COAD4 1Ichthyology and Molecular Systematics Research Laboratory, Zoology Section, Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran 2Inland Waters Aquaculture Research Center. Iranian Fisheries Sciences Research Institute. Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization, Bandar Anzali, Iran 3Department of Natural Resources (Fisheries Division), Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan 84156-83111, Iran 4Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 6P4 Canada *Email: [email protected] Abstract: This checklist aims to reviews and summarize the results of the systematic and zoogeographical research on the Iranian inland ichthyofauna that has been carried out for more than 200 years. Since the work of J.J. Heckel (1846-1849), the number of valid species has increased significantly and the systematic status of many of the species has changed, and reorganization and updating of the published information has become essential. Here we take the opportunity to provide a new and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran based on literature and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history and new fish collections. This article lists 288 species in 107 genera, 28 families, 22 orders and 3 classes reported from different Iranian basins. However, presence of 23 reported species in Iranian waters needs confirmation by specimens. -

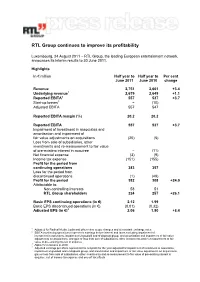

RTL Group Continues to Improve Its Profitability

RTL Group continues to improve its profitability Luxembourg, 24 August 2011 − RTL Group, the leading European entertainment network, announces its interim results to 30 June 2011. Highlights In € million Half year to Half year to Per cent June 2011 June 2010 change Revenue 2,751 2,661 +3.4 Underlying revenue1 2,679 2,649 +1.1 Reported EBITA2 557 537 +3.7 Start-up losses3 − (10) Adjusted EBITA 557 547 Reported EBITA margin (%) 20.2 20.2 Reported EBITA 557 537 +3.7 Impairment of investment in associates and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions (20) (5) Loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments and re-measurement to fair value of pre-existing interest in acquiree − (11) Net financial expense (3) (9) Income tax expense (151) (155) Profit for the period from continuing operations 383 357 Loss for the period from discontinued operations (1) (49) Profit for the period 382 308 +24.0 Attributable to: Non-controlling interests 58 51 RTL Group shareholders 324 257 +26.1 Basic EPS continuing operations (in €) 2.12 1.99 Basic EPS discontinued operations (in €) (0.01) (0.32) Adjusted EPS (in €)4 2.06 1.90 +8.4 1 Adjusted for Radical Media, Ludia and other minor scope changes and at constant exchange rates 2 EBITA (continuing operations) represents earnings before interest and taxes excluding impairment of investment in associates, impairment of goodwill and of disposal group, and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions, and gain or loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments -

Fl Begiltlteri Fiuide Tu

flBegiltlteri fiuidetu Iullrtru rtln g Ifl |jll lve rre Iheffiuthemuticul flrchetgpBrnfllnttlre, frt,rlld Icience [|lrttnrrI ftttnn[tR HARPTFI NEW Y ORK LO NDON TORONTO SYDNEY Tomy parents, SaIIyand Leonard, for theirendless loae, guidance,snd encouragement. A universal beauty showed its face; T'heinvisible deep-fraught significances, F1eresheltered behind form's insensible screen, t]ncovered to him their deathless harmony And the key to the wonder-book of common things. In their uniting law stood up revealed T'hemultiple measures of the uplifting force, T'helines of tl'reWorld-Geometer's technique, J'he enchantments that uphold the cosmic rveb And the magic underlving simple shapes. -Sri AurobitrdoGhose (7872-1950, Irrdinnspiritunl {uide, pttet ) Number is the within of all things. -Attributctl to Ptlfltngorus(c. 580-500s.c., Gre ek Tililosopther nrr d rtuttI rc nut t ic inn ) f'he earth is rude, silent, incomprehensibie at first, nature is incomprehensible at first, Be not discouraged, keep on, there are dir.ine things well errvelop'd, I swear to vou there are dirrine beings more beautiful than words can tell. -Wnlt Whitmm fl819-1892,Americnn noet) Flducation is the irrstruction of the intellect in the laws of Nature, under which name I include not merely things and their forces,but men and their ways; and the fashioning of the affections and of the r,t'ill into an earnest and loving desire to move in harmony with those laws. -Thomas Henry Huxley (1 B 25-1 Bg 5, Ett glislth iolo gis t) Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi GEOMETRY AND THE QUEST FOR REALITY BY JOHN MICHELL xiii INTRODUCTION xvii MONAD WHOLLY ONE 2 DYAD IT TAKES TWO TO TANGO 21 3 TRIAD THREE-PART HARMONY 38 4 TETRAD MOTHER SUBSTANCE 60 5 PENTAD REGENERATION 96 6 HEXAD STRUCTURE-FUNCTION-ORDER 178 7 HEPTAD ENCHANTING VIRGIN 221 8 OCTAD PERIODIC RENEWAL 267 9 ENNE AD THE HORIZON 301 10 DECAD BEYOND NUMBER 323 EPILOGUE NOW THAT YOU'VE CONSTRUCTED THE UNIVERSE .. -

Green Belt Slowly Coming Together

Kemano, Kemano, Kemano She loved the outdoors 1 I Bountiful harvest Reaction to the death of the ~ Vicki Kryklywyj, the heart and soul / /Northern B.C, Winter Games project keeps rolling in by,fax, mail of local hikers, is / / athletes cleaned up in Williams,, and personal delivery/NEWS A5 : remembered/COMMUNITY B1 j /Lake this year/SPORTS Cl I • i! ':i % WEDNESDAY FEBROARY 151 1995 I'ANDAR. /iiii ¸ :¸!ilii if!// 0 re n d a t i p of u n kn own ice b e rg" LIKE ALL deals in the world of tion Corp. effective April 30, the That title is still held by original "They've phoned us and have and the majority of its services, lulose for its Prince Rupert pulp high finance, the proposed amal- transfer of Orenda's forest licorice owners Avenor Inc. of Montreal requested a meeting but there's induding steam and effluent mill for the next two years. gamation of Orenda Forest Pro- must be approved by the provin- and a group of American newspa- been no confirmation of a time treaUnent, are tied to the latter. Even should all of the Orenda duels with a mostly American cial government. per companies. for that meeting," said Archer Avenor also owns and controls pulp fibre end up at Gold River, it company is more complicated There's growing opposition to The partuership built the mill in official Norman Lord from docking facilities and a chipper at still will fall short of the 5130,000 than it first seems. the move to take wood from the the late 1980s but dosed it in the Montreal last week. -

Catalog INTERNATIONAL

اﻟﻤﺆﺗﻤﺮ اﻟﻌﺎﻟﻤﻲ اﻟﻌﺸﺮون ﻟﺪﻋﻢ اﻻﺑﺘﻜﺎر ﻓﻲ ﻣﺠﺎل اﻟﻔﻨﻮن واﻟﺘﻜﻨﻮﻟﻮﺟﻴﺎ The 20th International Symposium on Electronic Art Ras al-Khaimah 25.7833° North 55.9500° East Umm al-Quwain 25.9864° North 55.9400° East Ajman 25.4167° North 55.5000° East Sharjah 25.4333 ° North 55.3833 ° East Fujairah 25.2667° North 56.3333° East Dubai 24.9500° North 55.3333° East Abu Dhabi 24.4667° North 54.3667° East SE ISEA2014 Catalog INTERNATIONAL Under the Patronage of H.E. Sheikha Lubna Bint Khalid Al Qasimi Minister of International Cooperation and Development, President of Zayed University 30 October — 8 November, 2014 SE INTERNATIONAL ISEA2014, where Art, Science, and Technology Come Together vi Richard Wheeler - Dubai On land and in the sea, our forefathers lived and survived in this environment. They were able to do so only because they recognized the need to conserve it, to take from it only what they needed to live, and to preserve it for succeeding generations. Late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan viii ZAYED UNIVERSITY Ed unt optur, tet pla dessi dis molore optatiist vendae pro eaqui que doluptae. Num am dis magnimus deliti od estem quam qui si di re aut qui offic tem facca- tiur alicatia veliqui conet labo. Andae expeliam ima doluptatem. Estis sandaepti dolor a quodite mporempe doluptatus. Ustiis et ium haritatur ad quaectaes autemoluptas reiundae endae explaboriae at. Simenis elliquide repe nestotae sincipitat etur sum niminctur molupta tisimpor mossusa piendem ulparch illupicat fugiaep edipsam, conecum eos dio corese- qui sitat et, autatum enimolu ptatur aut autenecus eaqui aut volupiet quas quid qui sandaeptatem sum il in cum sitam re dolupti onsent raeceperion re dolorum inis si consequ assequi quiatur sa nos natat etusam fuga. -

The Book of Revelation: Introduction by Jim Seghers

The Book of Revelation: Introduction by Jim Seghers Authorship It has been traditionally believed that the author of the Book of Revelation, also called the Apocalypse, was St. John the Apostle, the author of the Gospel and Epistles that bears his name. This understanding is supported by the near unanimous agreement of the Church Fathers. However, what we learn from the text itself is that the author is a man named John (Rev 1:1). Arguing against John the evangelist’s authorship is the fact that the Greek used in the Book of Revelation is strikingly different from the Greek John used in the fourth gospel. This argument is countered by those scholars who believe that the Book of Revelation was originally written in Hebrew of which our Greek text is a literal translation. The Greek text does bear the stamp of Hebrew thought and composition. In addition there are many expressions and ideas found in the Book of Revelation which only find a parallel in John’s gospel. Many modern scholars have the tendency to focus almost exclusively on the literary aspects of the sacred books along with a predisposition to reject the testimony of the Church Fathers. Therefore, many hold that another John, John the Elder or John the Presbyter [Papias refers to a John the Presbyter who lived in Ephesus], is the author of the Apocalypse. One scholar, J. Massyngberde Ford, provides the unique suggestion that John the Baptist is the author of the Book of Revelation ( Revelation: The Anchor Bible , pp. 28-37). Until there is persuasive evidence to the contrary, it is safe to conclude that St. -

“Temple of My Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal's

“Temple of my Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal’s Hindu Bangladeshi Community Aditya N. Bhattacharjee School of Religious Studies McGill University Montréal, Canada A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2017 © 2017 Aditya Bhattacharjee Bhattacharjee 2 Abstract In this thesis, I offer new insight into the Hindu Bangladeshi community of Montreal, Quebec, and its relationship to community religious space. The thesis centers on the role of the Montreal Sanatan Dharma Temple (MSDT), formally inaugurated in 2014, as a community locus for Montreal’s Hindu Bangladeshis. I contend that owning temple space is deeply tied to the community’s mission to preserve what its leaders term “cultural authenticity” while at the same time allowing this emerging community to emplace itself in innovative ways in Canada. I document how the acquisition of community space in Montreal has emerged as a central strategy to emplace and renew Hindu Bangladeshi culture in Canada. Paradoxically, the creation of a distinct Hindu Bangladeshi temple and the ‘traditional’ rites enacted there promote the integration and belonging of Bangladeshi Hindus in Canada. The relationship of Hindu- Bangladeshi migrants to community religious space offers useful insight on a contemporary vision of Hindu authenticity in a transnational context. Bhattacharjee 3 Résumé Dans cette thèse, je présente un aperçu de la communauté hindoue bangladaise de Montréal, au Québec, et surtout sa relation avec l'espace religieux communautaire. La thèse s'appuie sur le rôle du temple Sanatan Dharma de Montréal (MSDT), inauguré officiellement en 2014, en tant que point focal communautaire pour les Bangladeshis hindous de Montréal. -

Biblical Spirituality

THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM Ascertaining the literary dependence of the Synoptic Gospels constitutes what is commonly termed the Synoptic Problem. Site to compare Gospels: http://sites.utoronto.ca/religion/synopsis/ A. Similarities between the Synoptic Gospels 1. Common Material: Matthew Mark Luke Total Verses: 1,068 661 1,149 Triple Tradition (verses): 330 330 330 Double Tradition: 235 235 Note the similarity of the following pericopes: Matt 19:13-15/Mark 10:13-16/Luke 18:15-17 Matt 24:15-18/Mark 13:14-16/Luke 21:20-22 Matt 3:3; Mark 1:3; Luke 3:4 (Note the text of Isa 40:3 reads in the Septuagint: “Make straight the paths of our God,” and in the Hebrew “Make straight in the wilderness a highway for our God.”). Matthew 22:37; Mark 12:30; Luke 10:27 (This biblical quotation does not agree with the Hebrew text, which mentions heart and not mind, nor the Greek which never combines both heart and mind).1 2. Basic Agreement in Structure: Mark Matthew Luke a. Introduction to Ministry: 1:1-13 3:1-4, 11 3:1-4, 13 b. Galilean Ministry: 1:14-19, 50 4:12-18, 35 4:14-19, 50 c. Journey to Jerusalem: 10:1-52 19:1-20, 34 9:51-19:41 d. Death and Resurrection: chs. 11-16 chs. 21-28 chs. 19-24 3. Triple Tradition: An examination of “triple tradition,” reveals that while there is much material which is similar to all three Gospels, there is a good amount of material that show agreements between Matthew and Mark, and also Mark and Luke, but there is almost no material in the triple tradition that is common to Matthew and Luke (Matt 9:1-2; Mark 2:1-5; Luke 5:17-20). -

The Apocalypse of John;

BS 2825.4 .B39 c.l Beckwith, Isbon T. The apocalypse of John THE APOCALYPSE OF JOHN ^ '^^ o *^ ^ THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO ■DALLAS ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO /-<v\'( or p;i/;v22>> FEL3 :■) 1932 ^ .^ THE ^ ""^^ APOCALYPSE OF JOH]^ STUDIES IN INTRODUCTION WITH A CRITICAL AND EXEGETICAL COMMENTARY / BY ISBON T. BECKWITH, Ph.D., D.D. FORMERLY PROFESSOR OF THE INTERPRETATION OF THE NEW TESTAMENT IN THE GENERAL THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, NEW YORK, AND OF GREEK IN TRINITY COLLEGE, HARTFORD THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1919 All rights reserved COPTEIQHT. 1919, By the MACMILLAN COMPANY. Set up and electrotyped. Published November, 1915, NortoooU ^rc28 J. S. Gushing Co. — Berwick <fe Smith Co. Norwood, Mass., U.S.A. PREFACE For the understanding of the Revelation of John it is essen- tial to put one's self, as far as is possible, into the world of its author and of those to whom it was first addressed. Its mean- ing must be sought for in the light thrown upon it by the con- dition and circumstances of its readers, by the author's inspired purpose, and by those current beliefs and traditions that not only influenced the fashion which his visions themselves took, but also and especially determined the form of this literary composition in which he has given a record of his visions. These facts will explain what might seem the disproportionate space which I have given to some topics in the following Intro- ductory Studies. -

Hosseini, Mahrokhsadat.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Iranian Women’s Poetry from the Constitutional Revolution to the Post-Revolution by Mahrokhsadat Hosseini Submitted for Examination for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Gender Studies University of Sussex November 2017 2 Submission Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Mahrokhsadat Hosseini Signature: . Date: . 3 University of Sussex Mahrokhsadat Hosseini For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Gender Studies Iranian Women’s Poetry from the Constitutional Revolution to the Post- Revolution Summary This thesis challenges the silenced voices of women in the Iranian written literary tradition and proposes a fresh evaluation of contemporary Iranian women’s poetry. Because the presence of female poets in Iranian literature is a relatively recent phenomenon, there are few published studies describing and analysing Iranian women’s poetry; most of the critical studies that do exist were completed in the last three decades after the Revolution in 1979. -

COMMENTARY on REVELATION by Adam Clarke

THE WESLEYAN HERITAGE LIBRARY COMMENTARY COMMENTARY ON REVELATION by Adam Clarke. “Follow peace with all men, and holiness, without which no man shall see the Lord” Heb 12:14 Spreading Scriptural Holiness to the World Wesleyan Heritage Publications © 2002 2 A COMMENTARY AND CRITICAL NOTES ON THE HOLY BIBLE OLD AND NEW TESTAMENTS DESIGNED AS A HELP TO A BETTER UNDERSTANDING OF THE SACRED WRITINGS BY ADAM CLARKE, LL.D., F.S.A., &c. A NEW EDITION, WITH THE AUTHOR’S FINAL CORRECTIONS For whatsoever things were written aforetime were written for our learning, that we through patience and comfort of the Scriptures might have hope.—Rom. 15:4. Adam Clarke’s Commentary on the Old and New Testaments A derivative of Adam Clarke’s Commentary for the Online Bible produced by Sulu D. Kelley 1690 Old Harmony Dr. Concord, NC 28027-8031 (704) 782-4377 © 1994, 1995, 1997 © 1997 Registered U.S. Copyright Office 3 INTRODUCTION TO THE REVELATION OF ST. JOHN THE DIVINE AS there has been much controversy concerning the authenticity of this book; and as it was rejected by many for a considerable time, and, when generally acknowledged, was received cautiously by the Church; it will be well to examine the testimony by which its authenticity is supported, and the arguments by which its claim to a place in the sacred canon is vindicated. Before, therefore, I produce my own sentiments, I shall beg leave to lay before the reader those of Dr. Lardner, who has treated the subject with much judgment. “We are now come to the last book of the New Testament, the Revelation; about which there have been different sentiments among Christians; many receiving it as the writing of John the apostle and evangelist, others ascribing it to John a presbyter, others to Cerinthus, and some rejecting it, without knowing to whom it should be ascribed. -

Current Issues in Christology Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary Pastors Institute, 1993 by Wilbert R

Current Issues In Christology Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary Pastors Institute, 1993 By Wilbert R. Gawrisch I. The Contemporary Christological Scene It was the summer of 1978. Five professors of Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary were conducting the first Summer Quarter in Israel involving an archaeological dig at Tel Michal on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and a study tour of the country. In the far north of Palestine at the foot of snow-capped Mount Hermon rising more than 9000 feet above sea level, the professors and their tour group stopped at ancient Panias, now called Banias, to dangle their feet in the cold, crystal-clear waters of the Springs of Pan. The waters pour from a sheer, rocky cliff and combine to create the Banias River. Tumbling over picturesque falls, the Banias then merges with the white water of the Dan and Hazbani Rivers to form the famed Jordan River. This beautiful area was the site of ancient Caesarea Philippi. Here Herod the Great had built a temple of fine marble for the idol Pan and dedicated it to the Roman emperor Caesar Augustus. Herod’s son Philip the Tetrarch enlarged and beautified the city and changed its name to Caesarea Philippi to honor Tiberias Caesar, the stepson of Caesar Augustus, and himself. It was to this scenic region, about 30 miles north of the Sea of Galilee, that Jesus withdrew with his disciples before he went to Judea to suffer and die. The inhabitants of this area were for the most part Gentiles. Here Jesus sought escape from the crowds that dogged his steps in his Galilean ministry.