The Foreign Composer in Britain After World War II Ivan Moody1 Како Живети У Туђини

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium Programme

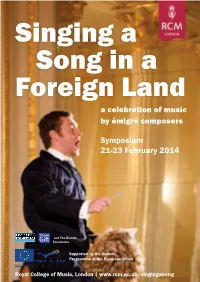

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

Hercules: Celebrity Strongman Or Kindly Deliverer?

Hercules: Celebrity Strongman or Kindly Deliverer? BY J. LARAE FERGUSON When Christoph Willibald Gluck’s French Alceste premiered in Paris on 23 April 1776, the work met with mixed responses. Although the French audience loved the first and second acts for their masterful staging and thrilling presentation, to them the third act seemed unappealing, a mere tedious extension of what had come before it. Consequently, Gluck and his French librettist Lebland Du Roullet returned to the drawing board. Within a mere two weeks, however, their alterations were complete. The introduction of the character Hercules, a move which Gluck had previously contemplated but never actualized, transformed the denouement and eventually brought the opera to its final popular acclaim. Despite Gluck’s sagacious wager that adding the character of Hercules would give to his opera the variety demanded by his French audience, many of his followers then and now admit that something about the character does not fit, something of the essential nature of the drama is lost by Hercules’ abrupt insertion. Further, although many of Gluck’s supporters maintain that his encouragement of Du Roullet to reinstate Hercules points to his acknowledged desire to adhere to the original Greek tragedy from which his opera takes its inspiration1, a close examination of the relationship between Gluck’s Hercules and Euripides’ Heracles brings to light marked differences in the actions, the purpose, and the characterization of the two heroes. 1 Patricia Howard, for instance, writes that “the difference between Du Roullet’s libretto and Calzabigi’s suggests that Gluck might have been genuinely dissatisfied at the butchery Calzabigi effected on Euripides, and his second version was an attempt not so much at a more French drama as at a more classically Greek one.” Patricia Howard, “Gluck’s Two Alcestes: A Comparison,” Musical Times 115 (1974): 642. -

Perceptual Interactions of Pitch and Timbre: an Experimental Study on Pitch-Interval Recognition with Analytical Applications

Perceptual interactions of pitch and timbre: An experimental study on pitch-interval recognition with analytical applications SARAH GATES Music Theory Area Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University Montréal • Quebec • Canada August 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. Copyright © 2015 • Sarah Gates Contents List of Figures v List of Tables vi List of Examples vii Abstract ix Résumé xi Acknowledgements xiii Author Contributions xiv Introduction 1 Pitch, Timbre and their Interaction • Klangfarbenmelodie • Goals of the Current Project 1 Literature Review 7 Pitch-Timbre Interactions • Unanswered Questions • Resulting Goals and Hypotheses • Pitch-Interval Recognition 2 Experimental Investigation 19 2.1 Aims and Hypotheses of Current Experiment 19 2.2 Experiment 1: Timbre Selection on the Basis of Dissimilarity 20 A. Rationale 20 B. Methods 21 Participants • Stimuli • Apparatus • Procedure C. Results 23 2.3 Experiment 2: Interval Identification 26 A. Rationale 26 i B. Method 26 Participants • Stimuli • Apparatus • Procedure • Evaluation of Trials • Speech Errors and Evaluation Method C. Results 37 Accuracy • Response Time D. Discussion 51 2.4 Conclusions and Future Directions 55 3 Theoretical Investigation 58 3.1 Introduction 58 3.2 Auditory Scene Analysis 59 3.3 Carter Duets and Klangfarbenmelodie 62 Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux • Carter and Klangfarbenmelodie: Examples with Timbral Dissimilarity • Conclusions about Carter 3.4 Webern and Klangfarbenmelodie in Quartet op. 22 and Concerto op 24 83 Quartet op. 22 • Klangfarbenmelodie in Webern’s Concerto op. 24, mvt II: Timbre’s effect on Motivic and Formal Boundaries 3.5 Closing Remarks 110 4 Conclusions and Future Directions 112 Appendix 117 A.1,3,5,7,9,11,13 Confusion Matrices for each Timbre Pair A.2,4,6,8,10,12,14 Confusion Matrices by Direction for each Timbre Pair B.1 Response Times for Unisons by Timbre Pair References 122 ii List of Figures Fig. -

Grieg Piano Concerto in a Minor Shee

Grieg piano concerto in a minor shee Continue Piano Concerto in the minor is directing here. See the piano concerto (Schumann) for the Robert Schumann concert. Music scores are temporarily disabled. Famously a flourishing introduction to concerts. Piano Concerto in Underage Op. 16, composed by Edvard Grieg in 1868, was the only concert Grieg finished. It is one of his most popular works[1] and is one of the most popular piano concertoes. Structure Musical scores are temporarily disabled. The main topic of allegro molto moderato. The concert is in three movements:[2] Allegro molto moderato (minor) The first movement is in sonata form and is known as timpani roll in its first bar, which leads to a dramatic piano bloom, which leads to the main theme. Then the key becomes a C large, secondary theme. Later the secondary theme appears again recapitulation, but this time the key major. The movement ends with virtuosic cadenza and bloom similar to that at the beginning of the movement. Adagio (D♭) The second movement is the lyrical movement D♭ large, leading directly to the third movement. The movement is in three-set form (A-B-A). Part B is D♭ and E large, then returns to D♭ a large reprise piano. Allegro moderato molto e marcato - Quasi presto - Andante maestoso (minor → F large → minor → large) the third movement opens a minor 24 times energetic theme (Theme 1), followed by a lyrical theme F large (Theme 2). The move will return to the theme on 1 January 2017. After this total cepteption is 34 main Quasi presto section, consisting of a variation of theme 1. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

I Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity Through the Oeuvre of Strauss And

Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity through the Oeuvre of Strauss and Hofmannsthal by Solveig M. Heinz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Germanic Languages and Literatures) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Vanessa H. Agnew, Chair Associate Professor Naomi A. André Associate Professor Andreas Gailus Professor Julia C. Hell i For John ii Acknowledgements Writing this dissertation was an intensive journey. Many people have helped along the way. Vanessa Agnew was the most wonderful Doktormutter a graduate student could have. Her kindness, wit, and support were matched only by her knowledge, resourcefulness, and incisive critique. She took my work seriously, carefully reading and weighing everything I wrote. It was because of this that I knew my work and ideas were in good hands. Thank you Vannessa, for taking me on as a doctoral rookie, for our countless conversations, your smile during Skype sessions, coffee in Berlin, dinners in Ann Arbor, and the encouragement to make choices that felt right. Many thanks to my committee members, Naomi André, Andreas Gailus, and Julia Hell, who supported the decision to work with the challenging field of opera and gave me the necessary tools to succeed. Their open doors, email accounts, good mood, and guiding feedback made this process a joy. Mostly, I thank them for their faith that I would continue to work and explore as I wrote remotely. Not on my committee, but just as important was Hartmut. So many students have written countless praises of this man. I can only concur, he is simply the best. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

View Becomes New." Anton Webern to Arnold Schoenberg, November, 25, 1927

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Catalogue 74 The Collection of Jacob Lateiner Part VI ARNOLD SCHOENBERG 1874-1951 ALBAN BERG 1885-1935 ANTON WEBERN 1883-1945 6 Waterford Way, Syosset NY 11791 USA Telephone 561-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). To avoid disappointment, we suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper left of our homepage. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. An 8.625% sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. International customers are asked to kindly remit in U.S. funds (drawn on a U.S. bank), by international money order, by electronic funds transfer (EFT) or automated clearing house (ACH) payment, inclusive of all bank charges. If remitting by EFT, please send payment to: TD Bank, N.A., Wilmington, DE ABA 0311-0126-6, SWIFT NRTHUS33, Account 4282381923 If remitting by ACH, please send payment to: TD Bank, 6340 Northern Boulevard, East Norwich, NY 11732 USA ABA 026013673, Account 4282381923 All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. Fine Items & Collections Purchased Please visit our website at www.lubranomusic.com where you will find full descriptions and illustrations of all items Members Antiquarians Booksellers’ Association of America International League of Antiquarian Booksellers Professional Autograph Dealers’ Association Music Library Association American Musicological Society Society of Dance History Scholars &c. -

The Early Works of Roberto Gerhard

9 ‘Un Català Mundial’: The early works of Roberto Gerhard Mark E. Perry ABSTRACT In the evaluation of the Catalan-born composer’s total oeuvre, the early works of Roberto Gerhard reflect the shifting cultural discourse within Catalan nationalism at the beginning of the twentieth century. As a means of fostering cultural independence from the rest of Spain, Catalan national sentiment gradually switched to the promotion of modernist ideologies, which were previously fended off in the defense and preservation of traditional culture. During this period under investigation, Gerhard was 'un català mundial' (an international Catalan), longing to participate in the greater musical world of the avant-garde. His musical activities in composition, research, and criticism echoed the shifting cultural discourse within Catalonia—Barcelona in particular. Active in nearly all aspects of musical life in the Catalan capital, Gerhard composed works that exhibited an intricate reconciliation of traditional Catalan elements with modern Central European musical aesthetics. Alongside painter Joan Miró, architect Josep Luís Sert, and arts promoter Joan Prats i Vallès, Gerhard established the Amics de l’Art Nou (ADLAN), promoting Catalan avant-garde art. Gerhard, with the assistance of cellist and conductor Pau Casals, brought Arnold Schoenberg to Catalonia for multiple performances of the Viennese master’s music. Gerhard further introduced modern music to the Catalan public with the ISCM festival held in Barcelona in 1936. This paper is informed by critical examination of period documents and contextualizes many of his early works within the escalating cultural movement that promoted modernization in the arts as a manifestation of Catalan national sentiment. -

Emigremusicianspdf.Pdf

Short biographies and sources for further information About the sources: Extensive biographies and information about compositions, recordings, careers and families of émigré musicians can be found in German in the excellent LexM online encyclopedia of musicians persecuted by the Nazis, hosted by the University of Hamburg. English-language information about many émigrés can be found on Wikipedia. I am indebted for many details to Jutta Raab Hansen, author of NS-verfolgte Musiker in England (Hamburg: Bockel Verlag, 1996), who interviewed many émigré musicians in London during the 1990s and published nearly 300 short biographies in her book. Norbert Meyn Bing, Rudolf Born 9.1.1902 in Vienna, died 2.9.1997 in New York From 1928 opera manager Darmstadt, then Städtische Oper Berlin 1930-33 Emigration to UK in 1934 1936-1949 general manager of Glyndebourne opera Founding director of the Edinburgh Festival 1947 General manager of Metropolitain Opera New York 1950-1972 Raab Hansen, p. 397 Brainin, Norbert Born 12.3.1923 in Vienna, died April 10, 2005 in London Emigration to UK in 1938 Violin studies with Carl Flesch and Max Rostal in London 1940 internment Isle of Man concerts with Ferdinand Rauter and Paul Hamburger Work as a metal worker duringt he war 1948-1987 1st violin in Amadeus Quartet with Sigmund Nissel, Peter Schidlof (both also émigrés) and Marin Lovett, over 4000 concerts http://www.lexm.uni-hamburg.de/object/lexm_lexmperson_00002549 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l06wDJIjQ2M Raab Hansen, p. 399 Busch, Fritz Born 13.3.1890 in Siegen, died 14.9.1951 in London Started as opera conductor in Riga, Aachen and Stuttgart 1922-1934 music director of Dresden Opera Nazi persecution for political reasons, Busch was not Jewish 1934-1939 music director of Glyndebourne Festival Opera, international conducting career, Teatro Colon Buenos Aires, Metropolitain Opera New York, Chicago, Copenhagen, Stockholm http://www.lexm.uni-hamburg.de/object/lexm_lexmperson_00001742 Raab Hansen, p. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Bitstream 46447.Pdf

I/2021 Музичка критика у Русији и Источној Европи У знак сећања на Стјуарта Кембела (1949–2018) Music Criticism in Russia and Eastern Europe In memoriam Stuart Campbell (1949–2018) Гост уредник Ивана Медић Guest Editor Ivana Medić Музикологија Часопис Музиколошког института САНУ Musicology Jоurnal of the Institute of Musicology SASA ~ 30 (I/2021) ~ ГЛАВНИ И ОДГОВОРНИ УРЕДНИК / EDITOR-IN-CHIЕF Александар Васић / Aleksandar Vasić РЕДАКЦИЈА / ЕDITORIAL BOARD Ивана Весић, Јелена Јовановић, Данка Лајић Михајловић, Ивана Медић, Биљана Милановић, Весна Пено, Катарина Томашевић / Ivana Vesić, Jelena Jovanović, Danka Lajić Mihajlović, Ivana Medić, Biljana Milanović, Vesna Peno, Katarina Tomašević СЕКРЕТАР РЕДАКЦИЈЕ / ЕDITORIAL ASSISTANT Милош Браловић / Miloš Bralović МЕЂУНАРОДНИ УРЕЂИВАЧКИ САВЕТ / INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL COUNCIL Светислав Божић (САНУ), Џим Семсон (Лондон), Алберт ван дер Схоут (Амстердам), Јармила Габријелова (Праг), Разија Султанова (Лондон), Денис Колинс (Квинсленд), Сванибор Петан (Љубљана), Здравко Блажековић (Њујорк), Дејв Вилсон (Велингтон), Данијела Ш. Берд (Кардиф) / Svetislav Božić (SASA), Jim Samson (London), Albert van der Schoot (Amsterdam), Jarmila Gabrijelova (Prague), Razia Sultanova (Cambridge), Denis Collins (Queensland), Svanibor Pettan (Ljubljana), Zdravko Blažeković (New York), Dave Wilson (Wellington), Danijela S. Beard (Cardiff) Музикологија је рецензирани научни часопис у издању Музиколошког института САНУ. Посвећен је проучавању музике као естетског, културног, историјског и друштвеног феномена и примарно усмерен на музиколошка и етномузиколошка истраживања. Редакција такође прихвата интердисциплинарне радове у чијем је фокусу музика. Часопис излази два пута годишње. Упутства за ауторе се могу преузети овде: https://music.sanu.ac.rs/en/instructions-for-authors/ Musicology is a peer-reviewed journal published by the Institute of Musicology SASA (Belgrade). It is dedicated to the research of music as an aesthetical, cultural, historical and social phenomenon and primarily focused on musicological and ethnomusicological research.