Download Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

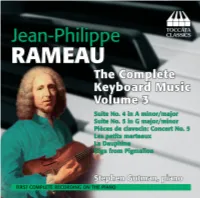

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

MOZARTEUM BAROQUE MASTERCLASSES Concerto Degli

International Festival & Summer Academy 2021 60 CONCERTI, FOCUS SU STEVE REICH con Salvatore Accardo · Antonio Pappano · Lilya Zilberstein · Ilya Gringolts Patrick Gallois · Alessandro Carbonare · David Krakauer · Antonio Meneses DavidSABATO Geringas · Bruno 4 SETTEMBRE Giuranna · Ivo Nilsson - ORE· Mathilde 21,15 Barthélémy AntonioCHIESA Caggiano ·DI Christian S. AGOSTINO, Schmitt · Clive Greensmith SIENA · Quartetto Prometeo Marcello Gatti · Florian Birsak · Alfredo Bernardini · Vittorio Ghielmi Roberto Prosseda · Eliot Fisk · Andreas Scholl e tanti altri e con Orchestra dell’Accademia di Santa Cecilia · Orchestra della Toscana Coro Della Cattedrale Di SienaCHIGIANA “Guido Chigi Saracini - MOZARTEUM” . BAROQUE MASTERCLASSES 28 CORSI E SEMINARI NUOVA COLLABORAZIONEConcerto CON degli Allievi CHIGIANA-MOZARTEUM BAROQUE MASTERCLASSES docenti ANDREAS SCHOLL canto barocco MARCELLO GATTI flauto traversiere ALFREDO BERNARDINI oboe barocco VITTORIO GHIELMI viola da gamba FLORIAN BIRSAK clavicembalo e basso continuo maestri collaboratori al clavicembalo Alexandra Filatova Andreas Gilger Gabriele Levi François Couperin Parigi 1668 - Parigi 1733 da Les Nations (1726) Quatrième Ordre “La Piemontoise” Martino Arosio flauto traversiere (Italia) Micaela Baldwin flauto traversiere (Italia / Perù) Laura Alvarado Diaz oboe (Colombia) Amadeo Castille oboe (Francia) Alice Trocellier viola da gamba (Francia) Raimondo Mazzon clavicembalo (Italia) Georg Friedrich Händel Halle 1685 - Londra 1759 da Orlando (1733) Amore è qual vento Rui Hoshina soprano (Giappone) -

Download Booklet

95779 The viola da gamba (or ‘leg-viol’) is so named because it is held between the legs. All the members of the 17th century, that the capabilities of the gamba as a solo instrument were most fully realised, of the viol family were similarly played in an upright position. The viola da gamba seems to especially in the works of Marin Marais and Antoine Forqueray (see below, CD7–13). have descended more directly from the medieval fiddle (known during the Middle Ages and early Born in London, John Dowland (1563–1626) became one of the most celebrated English Renaissance by such names as ffythele, ffidil, fiele or fithele) than the violin, but it is clear that composers of his day. His Lachrimæ, or Seaven Teares figured in Seaven Passionate Pavans were both violin and gamba families became established at about the same time, in the 16th century. published in London in 1604 when he was employed as lutenist at the court of the Danish King The differences in the gamba’s proportions, when compared with the violin family, may be Christian IV. These seven pavans are variations on a theme, the Lachrimae pavan, derived from summarised thus – a shorter sound box in relation to the length of the strings, wider ribs and a flat Dowland’s song Flow my tears. In his dedication Dowland observes that ‘The teares which Musicke back. Other ways in which the gamba differs from the violin include its six strings (later a seventh weeps [are not] always in sorrow but sometime in joy and gladnesse’. -

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano

Five Late Baroque Works for String Instruments Transcribed for Clarinet and Piano A Performance Edition with Commentary D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of the The Ohio State University By Antoine Terrell Clark, M. M. Music Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Approved By James Pyne, Co-Advisor ______________________ Co-Advisor Lois Rosow, Co-Advisor ______________________ Paul Robinson Co-Advisor Copyright by Antoine Terrell Clark 2009 Abstract Late Baroque works for string instruments are presented in performing editions for clarinet and piano: Giuseppe Tartini, Sonata in G Minor for Violin, and Violoncello or Harpsichord, op.1, no. 10, “Didone abbandonata”; Georg Philipp Telemann, Sonata in G Minor for Violin and Harpsichord, Twv 41:g1, and Sonata in D Major for Solo Viola da Gamba, Twv 40:1; Marin Marais, Les Folies d’ Espagne from Pièces de viole , Book 2; and Johann Sebastian Bach, Violoncello Suite No.1, BWV 1007. Understanding the capabilities of the string instruments is essential for sensitively translating the music to a clarinet idiom. Transcription issues confronted in creating this edition include matters of performance practice, range, notational inconsistencies in the sources, and instrumental idiom. ii Acknowledgements Special thanks is given to the following people for their assistance with my document: my doctoral committee members, Professors James Pyne, whose excellent clarinet instruction and knowledge enhanced my performance and interpretation of these works; Lois Rosow, whose patience, knowledge, and editorial wonders guided me in the creation of this document; and Paul Robinson and Robert Sorton, for helpful conversations about baroque music; Professor Kia-Hui Tan, for providing insight into baroque violin performance practice; David F. -

| 216.302.8404 “An Early Music Group with an Avant-Garde Appetite.” — the New York Times

“CONCERTS AND RECORDINGS“ BY LES DÉLICES ARE JOURNEYS OF DISCOVERY.” — NEW YORK TIMES www.lesdelices.org | 216.302.8404 “AN EARLY MUSIC GROUP WITH AN AVANT-GARDE APPETITE.” — THE NEW YORK TIMES “FOR SHEER STYLE AND TECHNIQUE, LES DÉLICES REMAINS ONE OF THE FINEST BAROQUE ENSEMBLES AROUND TODAY.” — FANFARE “THE MEMBERS OF LES DÉLICES ARE FIRST CLASS MUSICIANS, THE ENSEMBLE Les Délices (pronounced Lay day-lease) explores the dramatic potential PLAYING IS IRREPROACHABLE, AND THE and emotional resonance of long-forgotten music. Founded by QUALITY OF THE PIECES IS THE VERY baroque oboist Debra Nagy in 2009, Les Délices has established a FINEST.” reputation for their unique programs that are “thematically concise, — EARLY MUSIC AMERICA MAGAZINE richly expressive, and featuring composers few people have heard of ” (NYTimes). The group’s debut CD was named one of the "Top “DARING PROGRAMMING, PRESENTED Ten Early Music Discoveries of 2009" (NPR's Harmonia), and their BOTH WITH CONVICTION AND MASTERY.” performances have been called "a beguiling experience" (Cleveland — CLEVELANDCLASSICAL.COM Plain Dealer), "astonishing" (ClevelandClassical.com), and "first class" (Early Music America Magazine). Since their sold-out New “THE CENTURIES ROLL AWAY WHEN York debut at the Frick Collection, highlights of Les Délices’ touring THE MEMBERS OF LES DÉLICES BRING activites include Music Before 1800, Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner THIS LONG-EXISTING MUSIC TO Museum, San Francisco Early Music Society, the Yale Collection of COMMUNICATIVE AND SPARKLING LIFE.” Musical Instruments, and Columbia University’s Miller Theater. Les — CLASSICAL SOURCE (UK) Délices also presents its own annual four-concert series in Cleveland art galleries and at Plymouth Church in Shaker Heights, OH, where the group is Artist in Residence. -

Forqueray Atsushi Sakai Christophe Rousset Marion Martineau Antoine Forqueray (1672-1745) Pièces De Viole

Forqueray Atsushi Sakai Christophe Rousset Marion Martineau Antoine Forqueray (1672-1745) Pièces de viole Enregistré au Temple Bon Secours à Paris du 6 au 9 juillet, puis du 22 au 25 septembre 2015 Atsushi Sakai Production exécutive et enregistrement : Little Tribeca Christophe Rousset Prise de son et direction artistique : Ken Yoshida Montage : Ignace Hauville, Atsushi Sakai et Ken Yoshida Mixage : Ken Yoshida et Nicolas Bartholomée Marion Martineau Clavecin d’après Ioannes Ruckers Anvers 1624 (collection du Musée Unterlinden de Colmar) – Marc Ducornet & Emmanuel Danset à Paris 1993 Basse de viole d'après Nicolas Bertrand Paris 1705 – François Bodart à Chastre 1988 (Atsushi Sakai) Basse de viole d'après Michel Collichon Paris 1693 (Collection du Musée d'Art et d'Histoire de Genève) – Judith Kraft à Paris 2008 (Marion Martineau) Photos © Sofia Albaric English translation by John Tyler Tuttle Aparté · Little Tribeca 1, rue Paul Bert 93500 Pantin, France AP122 © ℗ Little Tribeca 2015 Fabriqué en Europe apartemusic.com CD1 CD2 Quatrième Suite : Troisième Suite : 1. La Marella 4’21 1. La Ferrand 4’23 2. La Clément 9’27 2. La Régente 7’16 3. Sarabande. La D’Aubonne 7’22 3. La Tronchin 4’28 4. La Bournonville 3’29 4. La Angrave 4’18 5. La Sainscy 11’ 36 5. La Du Vaucel 7’15 6. Le Carillon de Passy - La Latour 12’40 6. La Eynaud 3’49 7. Chaconne. La Morangis ou La Plissay 8’26 Deuxième Suite : 7. La Bouron 5’14 Première Suite : 8. La Mandoline 8’07 8. Allemande. La La Borde 7’32 9. -

Aya Hamada Program

MUSIC BEFORE 1800 Louise Basbas, director Aya Hamada, harpsichord Portraits et Caractères Couperin, Rameau, Duphly Prélude non mesuré en mi mineur Louis Couperin (c. 1626 - 1661) La Superbe ou la Forqueray, fièrement, sans lenteur François Couperin (1668 - 1733) Troisième livre de pièces de clavecin, 17ème ordre (1722) Allemande La Couperin François D'Agincourt (1683 - 1759) Pièces de clavecin, dédiées à la Reine (1733) La Couperin, d'une vivacité modérée François Couperin Troisième livre de pièces de clavecin, 21ème ordre Quatre Suites de Pièces de clavecin, Op.59 (1736) Joseph Bodin de Boismortier (1689 - 1755) La Veloutée (pièce en rondeau) La Frénétique (pièce en rondeau) La Caverneuse, gracieusement (pièce en rondeau) La Rustique (pièce en rondeau) Pièces de clavessin (1724) Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683 - 1764) Les Tendres Plaintes (rondeau) Les Tourbillons (rondeau) L’Entretien des Muses Les Cyclopes (rondeau) Pièces de viole mises en pièces de clavecin, cinquième suite (1747) Antoine Forqueray (1671 - 1745) / La Rameau, majestueusement Jean-Baptiste Forqueray (1699 - 1782) La Silva, très tendrement Jupiter, modérément Troisième livre de pièces de clavecin (1756) Jacques Duphly (1715 - 1789) La Forqueray (rondeau) Les Grâces, tendrement Chaconne Tis program is followed by an interactive Q and A with Aya Hamada. Te program will be available to online subscribers/ticket holders until July 15. Te video production is supported, in part, by a generous gif from Roger and Whitney Bagnall. Tis program is sponsored, in part, by Nancy Hager. Tis program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. -

Aya Hamada Program Notes

PROGRAM NOTES J’ai toujours eu un objet en composant toutes ces pièces. Des occasions différentes me l'ont fourni, ainsi les titres répondent aux idées que j'en ai eues; on me dispensera d'en rendre compte . il est bon d'avertir que les pièces qui le portent sont des espèces de portraits, qu'on a trouvé quelquefois assez ressemblants sous mes doigts. I have always had an objective in mind when composing these pieces—objects that stood out to me on various occasions. Tus, the titles reflect ideas which I have had; please exempt me from explaining them further…. I should point out that the pieces which bear them are a type of portraits which, under my fingers, have on occasion been found to have a fair enough likeness. François Couperin, preface to the Premier livre de pièces de clavecin (1713) —translated by Aya Hamada In the 18th century during the reign of Louis XV, the harpsichord enjoyed its greatest popularity in France. A wealth of music for harpsichord was composed and ofen printed, which reflected the popularity of the instrument among professionals and amateurs. While the music of the previous Grand Siècle is full of majestic grandeur and solemn grace, the period of Louis XV tends to favor a refined elegance and lightness. In the early 18th century French harpsichord music that had developed from the dance suites of the 17th century had added many character pieces and dedicatory portraits. Bearing enigmatic and evocative titles taken from life’s experiences, the character pieces evoke moods, emotions, events, objects, natural phenomena, or specific situations. -

Paolo Pandolfo, Viola Da Gamba [Nicolas Bertrand, Late 17Th Century]

Paolo Pandolfo, viola da gamba [Nicolas Bertrand, late 17th century] Guido Balestracci, viola da gamba Rolf Lislevand, theorbo & Baroque guitar Eduardo Egüez, theorbo & Baroque guitar Guido Morini, harpsichord 5 Recorded in Montevarchi di Arezzo, Italy, in February 1994 and April 1995 Engineered by Luciano Contini and Valter Neri Digital editing: Carlos Céster Produced by Paolo Pandolfo and Luciano Contini Executive producer & editorial director: Carlos Céster Editorial assistance: María Díaz Design: Valentín Iglesias On the cover: Jean-Martial Frédou (1710-1795), after Louis-Michel Van Loo (1707-1771), Louis xv roi de France et de Navarre, en grand manteau royal (detail). Versailles, châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. Photo Gérard Blot © rmn Booklet essays: Edmond Lemaître, Pierre Jaquier Translations: Ivan Moody ( eng ), Bernd Neureuther ( deu ), Pedro Elías (Lemaître, esp ), Emilio Moreno ( Jaquier, esp ) © 2011 MusiContact GmbH Forqueray cd ii [71:06] Pièces de viole avec la basse continuë Troisième Suite Cinquième Suite (Paris, 1747) 1 La Ferrand 6:10 8 La Rameau 4:43 2 La Regente 6:31 9 La Guignon 4:00 Antoine Forqueray, le père (1672-1745) 3 La Tronchin 4:09 10 La Léon. Sarabande 4:09 4 La Angrave* 2:54 11 La Boisson 4:11 Jean-Baptiste Forqueray, le fils (1699-1782)* 5 La Du Vaucel* 4:13 12 La Montigni 6:25 6 La Eynaud 3:44 13 La Silva 4:14 7 Chaconne. La Morangis ou 14 Jupiter 7:40 La Plissay* 7:55 cd 1 [75:30] Première Suite Quatrième Suite 1 Allemande. La La Borde 6:24 12 La Marella 3:20 2 La Forqueray 2:15 13 La Clement 6:13 3 La Cottin 2:49 14 Sarabande. -

Programa De Mà Festival Llums D'antiga

MÚSICA ANTIGA 2018_2019 FESTIVAL LLUMS D’ANTIGA del 5 al 16 de febrer auditori.cat L’Auditori inicia enguany el Festival Llums d’Antiga amb UNA NIT AMB EL REI SOL DIMARTS, 5 FEBRER 2019 Església dels Sants Just LLETRA I MÚSICA D’UNA VETLLADA → 20 h i Pastor l’esperit d’apropar al públic repertoris, formacions, intèrprets i tipologies de concert poc habituals a les sales de concerts. ALS JARDINS DE VERSALLES AMB 29 € Pàg. 4 LLUÍS XIV Llums d’Antiga aposta per propostes arriscades i maneres NÚRIA RIAL DIJOUS, 7 FEBRER 2019 L’Auditori, innovadores de construir-les, les quals parteixen d’elements & ACCADEMIA DEL PIACERE → 20 h Sala 2 Oriol Martorell mínims per bastir programes sòlids i amb contingut. El festival SEBASTIÁN DURÓN: 29 € Pàg. 6 es construeix a través de dues línies principals, que cadascun MUERA CUPIDO dels concerts desenvolupa en diferents direccions. D’una banda, la figura de Lluís XIV, que va promoure generosament JEAN RONDEAU DIVENDRES, 8 FEBRER 2019 Capella de Santa Àgata PIÈCES DE CLAVECIN, → 20 h les arts a la seva cort com a mostra del seu poder absolut. Pàg. 12 De l’altra, Martí Luter, la reforma del qual ressona, cinc-cents DE COUPERIN 29 € CALENDARI DE CONCERTS CALENDARI CALENDARI DE CONCERTS DE CALENDARI anys més tard, amb més força que mai sobre un sistema FESTIVAL LLUMS D’ANTIGA LLUMS FESTIVAL socioeconòmic en fallida. Es convida el públic a filtrar-se per JUSTIN TAYLOR: DIUMENGE, 10 FEBRER 2019 Capella de Santa Àgata aquests escenaris, que un dia van ser tan reals com tot el que LA FAMILLE FORQUERAY → 19 h Pàg. -

Article Michaelstein

e baroque guitar in France, and its two main figures: Robert de Visée & François Campion by Gérard Rebours An article published in the Michaelsteiner Konferenzeberichte, band 66, following the lecture given in Nov. 2001 at the 22.Musikinstrumentenbau-Symposium, "Gitarre und Zister - Bauweuse, Spieltechnik und Geschichte bis 1800". Revised and completed in 2013. The baroque guitar in France is a wide-ranging subject, and although theses and dissertations have already been written about it, much still remains to be said. The following is merely a synthesis of what seems to have been the course of the instrument in France, from the 1600s to the end of the eighteenth century. The four-course "Renaissance guitar" was quite well developed in France in the mid-sixteenth century, where it had reached a very high musical level, often requiring quite a skilled playing technique. But, astonishingly enough, there does not seem to be a link, in France, between this fourcourse guitar and the five-course instrument, the so called "baroque guitar". In fact the latter does not appear to be a continuation of its predecessor: it is like an entirely new guitar, which continued to survive for around two centuries. And although this instrument's construction, stringing, technique and musical style often changed throughout these 180 or 200 years, it remained basically an instrument with five courses tuned: 4th-4th-3rd-4th. Below are the main points that will be developed during this article: some are peculiar to France, whereas some can also be observed in other countries. 1 - As far as we can rely on theorists, surviving music and tutors, literature and iconography, the five-course guitar was initially used only for strumming chords and, at the end of its life, was purely a plucked string instrument - therefore having a restricted technique at both ends, we could say. -

Rameau Program Notes

PROGRAM NOTES Jean-Philippe Rameau wrote his first operatic work, the “tragédie en musique” Hippolyte et Aricie, in 1733 at age fifty. By 1741, the year that he published the Pièces de clavecin en concerts, he had composed five operas altogether: two more tragédies en musique, Castor et Pollux in 1737 and Dardanus in 1739, and two opéra-ballets, Les Indes galantes in 1735 and Les fêtes d’Hébé in 1739. Although his Pièces de clavecin en concerts hark back to the solo harpsichord works of his earlier career, it is hardly surprising that the world of the theater is never far from them . In fact, several of the movements were later reworked for inclusion into his operas. Rameau’s carefully arranged textures for the three instruments—violin, viola da gamba, and harpsichord—fill the Pièces with all the imagination, passion, and drama that enliven his stage works. One can almost sense choreographic images in these stylistically mature pieces filled with operatic allusions, ravishing sonorities, and elevated nobleness. The practice of adding a violin to harpsichord works was well established in France by the middle of the century. Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre’s Pièces de clavecin qui peuvent se jouer sur le violon was published in 1707, and so was Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville’s Pièces de clavecin en sonates, Op.3, in 1734. Without mentioning Mondonville’s name, Rameau intimated the influence of his predecessor’s works in the preface to his Pièces de clavecin en concerts: “The success of recently published sonatas, which have come out