“And I Think to Myself – What a Marvel-Ous World” An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

Cornell Alumni News Volume 49, Number 7 November 15, 1946 Price 20 Cents

Cornell Alumni News Volume 49, Number 7 November 15, 1946 Price 20 Cents Dawson Catches a Pass from Burns in Yale Game on Schoellkopf Field "It is not the finding of a thing, but the making something out of it after it is found, that is of consequence ' —JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL Why some things get better all the time TAKE THE MODERN ELECTRIC LIGHT BULB, for ex- Producing better materials for the use of industry ample. Its parts were born in heat as high as 6,000° F. and the benefit of mankind is the work of Union ... in cold as low as 300° below zero . under crush- Carbide. ing pressure as great as 3,000 pounds per square inch. Basic knowledge and persistent research are re- Only in these extremes of heat, cold and pressure quired, particularly in the fields of science and en- did nature yield the metal tungsten for the shining gineering. Working with extremes of heat and cold, filament. argon, the colorless gas that fills the bulb and with vacuums and great pressures, Units of UCC . and the plastic that permanently seals the glass now separate or combine nearly one-half of the many to the metal stem. And it is because elements of the earth. of such materials that light bulbs today are better than ever before. The steady improvement of the TTNION CARBIDE V-/ AND CARBON CORPORATION electric light bulb is another in- stance of history repeating itself. For man has always Products of Divisions and Units include— had to have better materials before he could make ALLOYS AND METALS CHEMICALS PLASTICS ELECTRODES, CARBONS, AND BATTERIES better things. -

Oktober 1968 CM # 005 (20 Seiten) Autor: Arnold Drake, Zeichner: Don Heck, Inker: John Tartaglione Hit Comics Nr. 203 , 1970 Rä

CAPTAIN MARVEL Checkliste (klassische Deutsche Ausgaben 1967-1977) Marvel Super-Heroes (Vol. 1) # 12-13 Oktober 1968 (Dezember 1967 - März 1968) CM # 005“The Mark Of The Metazoid!” (20 Seiten) Captain Marvel (Vol. 1) # 1-14 Autor: Arnold Drake, Zeichner: Don Heck, (Mai 1968 - Juli 1969) Inker: John Tartaglione Hit Comics Nr. 203 Dezember 1967 „Der Angriff des Metazoids“, 1970 MSH # 12“The Coming Of Captain Marvel!” (15 Seiten) Autor: Stan Lee, Zeichner: Gene Colan, Inker: Frank Giacoia Rächer Nr. 12-15„Das Los des Metazoiden!“ , (keine deutsche Veröffentlichung) Dezember 1974-März 1975 Übersetzung: Hartmut Huff, März 1968 Lettering: C. Raschke/U. Mordek/ MSH # 13“Where Stalks The Sentry!” (20 Seiten) M. Gerson/U. Mordek Autor: Roy Thomas, Zeichner: Gene Colan, Inker: Paul Reinman November 1968 (keine deutsche Veröffentlichung) CM # 006“In The Path Of Solam!” (20 Seiten) Autor: Arnold Drake, Zeichner: Don Heck, Mai 1968 Inker: John Tartaglione CM # 001“Out Of The Holocaust - - A Hero!” (21 Seiten) Hit Comics Nr. 203 Autor: Roy Thomas, Zeichner: Gene Colan, „Die Macht des Solams“, 1970 Inker: Vince Colletta Hit Comics Nr. 121 Rächer Nr. 16-18„Auf Solams Spur!“ , „Ein Sieger ohnegleichen“, 1969 April-Juni 1975 Übersetzung: Hartmut Huff, Rächer Nr. 1-3„Der Kampf der Titanen!“ , Lettering: Marlies Gerson, Januar-März 1974 Ursula Mordek (Rächer 16) Lettering: Ursula Mordek (nur Seite 1-7) (Originalseite 15 fehlt) Juli 1968 CM # 002 “From The Void Of Space Comes-- The Super Skrull!” (20 Seiten) Autor: Roy Thomas, Zeichner: Gene Colan, Inker: Vince Colletta Hit Comics Nr. 121 „Der Angriff des Super-Skrull“, 1969 Rächer Nr. -

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

Blade II" (Luke Goss), the Reapers Feed Quickly

J.antie Lissow- knocks Starbucks, offers funny anecdotes By Jessica Besack has been steadily rising. stuff. If you take out a whole said, you might find "Daddy's bright !)ink T -shirt with the Staff Writer He is now signed under the shelf, it will only cost you $20." Little Princess" upon closer sparkly words "Daddy's Little Gersh Agency, which handles Starbucks' coffee was another reading. Princess" emblazoned across the Comedian Jamie Lissow other comics such as Dave object of Lissow's humor. He In conclusion to his routine, front. entertained a small audience in Chappele, Jim Breuer and The warned the audience to be cau Lissow removed his hooded You can read more about the Wolves' Den this past Friday Kids in the Hall. tious when ordering coffee there, sweatshirt to reveal a muscular Jamie Lissow at evening joking about Starbucks Lissow amused the audience since he has experienced torso bulging out of a tight, http://www.jamielissow.com. coffee, workout buffs, dollar with anecdotes of his experi mishaps in the process. stores and The University itself. ences while touring other col "I once asked 'Could I get a Lissow, who has appeared on leges during the past few weeks. triple caramel frappuccino "The Tonight Show with Jay At one college, he performed pocus-mocha?"' Lissow said, Leno" and NBC's "Late Friday," on a stage with no microphone "and the coffee lady turned into a opened his act with a comment after an awkward introduction, newt. I think I said it wrong." about the size of the audience, only to notice that halfway Lissow asked audience what saying that when he booked The through his act, students began the popular bars were for University show, he presented approaching the stage carrying University students. -

Aliens of Marvel Universe

Index DEM's Foreword: 2 GUNA 42 RIGELLIANS 26 AJM’s Foreword: 2 HERMS 42 R'MALK'I 26 TO THE STARS: 4 HIBERS 16 ROCLITES 26 Building a Starship: 5 HORUSIANS 17 R'ZAHNIANS 27 The Milky Way Galaxy: 8 HUJAH 17 SAGITTARIANS 27 The Races of the Milky Way: 9 INTERDITES 17 SARKS 27 The Andromeda Galaxy: 35 JUDANS 17 Saurids 47 Races of the Skrull Empire: 36 KALLUSIANS 39 sidri 47 Races Opposing the Skrulls: 39 KAMADO 18 SIRIANS 27 Neutral/Noncombatant Races: 41 KAWA 42 SIRIS 28 Races from Other Galaxies 45 KLKLX 18 SIRUSITES 28 Reference points on the net 50 KODABAKS 18 SKRULLS 36 AAKON 9 Korbinites 45 SLIGS 28 A'ASKAVARII 9 KOSMOSIANS 18 S'MGGANI 28 ACHERNONIANS 9 KRONANS 19 SNEEPERS 29 A-CHILTARIANS 9 KRYLORIANS 43 SOLONS 29 ALPHA CENTAURIANS 10 KT'KN 19 SSSTH 29 ARCTURANS 10 KYMELLIANS 19 stenth 29 ASTRANS 10 LANDLAKS 20 STONIANS 30 AUTOCRONS 11 LAXIDAZIANS 20 TAURIANS 30 axi-tun 45 LEM 20 technarchy 30 BA-BANI 11 LEVIANS 20 TEKTONS 38 BADOON 11 LUMINA 21 THUVRIANS 31 BETANS 11 MAKLUANS 21 TRIBBITES 31 CENTAURIANS 12 MANDOS 43 tribunals 48 CENTURII 12 MEGANS 21 TSILN 31 CIEGRIMITES 41 MEKKANS 21 tsyrani 48 CHR’YLITES 45 mephitisoids 46 UL'LULA'NS 32 CLAVIANS 12 m'ndavians 22 VEGANS 32 CONTRAXIANS 12 MOBIANS 43 vorms 49 COURGA 13 MORANI 36 VRELLNEXIANS 32 DAKKAMITES 13 MYNDAI 22 WILAMEANIS 40 DEONISTS 13 nanda 22 WOBBS 44 DIRE WRAITHS 39 NYMENIANS 44 XANDARIANS 40 DRUFFS 41 OVOIDS 23 XANTAREANS 33 ELAN 13 PEGASUSIANS 23 XANTHA 33 ENTEMEN 14 PHANTOMS 23 Xartans 49 ERGONS 14 PHERAGOTS 44 XERONIANS 33 FLB'DBI 14 plodex 46 XIXIX 33 FOMALHAUTI 14 POPPUPIANS 24 YIRBEK 38 FONABI 15 PROCYONITES 24 YRDS 49 FORTESQUIANS 15 QUEEGA 36 ZENN-LAVIANS 34 FROMA 15 QUISTS 24 Z'NOX 38 GEGKU 39 QUONS 25 ZN'RX (Snarks) 34 GLX 16 rajaks 47 ZUNDAMITES 34 GRAMOSIANS 16 REPTOIDS 25 Races Reference Table 51 GRUNDS 16 Rhunians 25 Blank Alien Race Sheet 54 1 The Universe of Marvel: Spacecraft and Aliens for the Marvel Super Heroes Game By David Edward Martin & Andrew James McFayden With help by TY_STATES , Aunt P and the crowd from www.classicmarvel.com . -

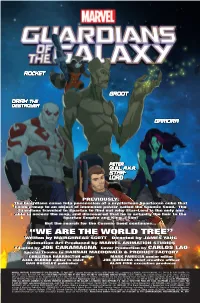

“We Are the World Tree”

PREVIOUSLY: The Guardians came into possession of a mysterious Spartaxan cube that holds a map to an object of immense power called the Cosmic Seed. The Guardians traveled to Spartax to fi nd out why Star-Lord is the only one able to access the map, and discovered that he is actually the heir to the Spartax Empire and King J’Son! But the search for the Cosmic Seed continues... “WE ARE THE WORLD TREE” Written by MAIRGHREAD SCOTT Directed by JAMES YANG Animation Art Produced by MARVEL ANIMATION STUDIOS Adapted by JOE CARAMAGNA Cover Production by CARLOS LAO Special Thanks to HANNAH MACDONALD & PRODUCT FACTORY CHRISTINA HARRINGTON editor MARK PANICCIA senior editor AXEL ALONSO editor in chief JOE QUESADA chief creative offi cer DAN BUCKLEY publisher ALAN FINE executive producer MARVEL UNIVERSE GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY No. 17, April 2017. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2017 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. $2.99 per copy in the U.S. (GST #R127032852) in the direct market; Canadian Agreement #40668537. Printed in the USA. Subscription rate (U.S. dollars) for 12 issues: U.S. $26.99; Canada $42.99; Foreign $42.99. POSTMASTER: SEND ALL ADDRESS CHANGES TO MARVEL UNIVERSE GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY, C/O MARVEL SUBSCRIPTIONS P.O. -

Writer Charles Soule Layouts Reilly Brown

BLINDED IN A FREAK ACCIDENT AS A CHILD, ATTORNEY MATT MURDOCK GAINED HEIGHTENED SENSES, ALLOWING HIM TO FIGHT CRIME AS DAREDEVIL. WHEN HIS FAMILY WAS MURDERED BY THE MOB, FORMER SOLDIER FRANK CASTLE RENOUNCED EVERYTHING EXCEPT VENGEANCE, BECOMING THE VIGILANTE KNOWN AS THE PUNISHER. PROSECUTOR MATT MURDOCK ARRANGED FOR GANGSTER SERGEY ANTONOV’S TRANSFER TO TEXAS, AS THE ACCUSED COULDN’T GET A FAIR TRIAL IN NEW YORK CITY. BUT A FAIR TRIAL BECAME THE LEAST OF THE GANGSTER’S WORRIES WHEN THE PUNISHER ATTACKED HIS PRISON TRANSPORT! DAREDEVIL AND HIS NEW PROTÉGÉ BLINDSPOT DISPENSED WITH PUNISHER AND GOT THE ACCUSED SAFELY TO QUEENS, ONLY TO BE AMBUSHED BY ANTONOV’S GOONS! TO MAKE MATTERS WORSE, FRANK CASTLE’S CAUGHT UP AND HE’S OUT FOR BLOOD… WRITER CHARLES SOULE LAYOUTS REILLY BROWN PENCILS & INKS SZYMON KUDRANSKI COLORS JIM CHARALAMPIDIS LETTERER VC’S CLAYTON COWLES PRODUCTION ANNIE CHENG PRODUCTION MANAGER TIM SMITH 3 ASSISTANT EDITOR CHARLES BEACHAM EDITOR JAKE THOMAS EDITOR IN CHIEF AXEL ALONSO CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER JOE QUESADA PUBLISHER DAN BUCKLEY EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALAN FINE DAREDEVIL/PUNISHER: SEVENTH CIRCLE No. 2, August 2016. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2016 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. -

Super Ticket Student Edition.Pdf

THE NATION’S NEWSPAPER Math TODAY™ Student Edition Super Ticket Sales Focus Questions: h What are the values of the mean, median, and mode for opening weekend ticket sales and total ticket sales of this group of Super ticket sales movies? Marvel Studio’s Avi Arad is on a hot streak, having pro- duced six consecutive No. 1 hits at the box office. h For each data set, determine the difference between the mean and Blade (1998) median values. Opening Total ticket $17.1 $70.1 weekend sales X-Men (2000) (in millions) h How do opening weekend ticket $54.5 $157.3 sales compare as a percent of Blade 2 (2002) total ticket sales? $32.5 $81.7 Spider-Man (2002) $114.8 $403.7 Daredevil (2003) $45 $102.2 X2: X-Men United (2003) 1 $85.6 $200.3 1 – Still in theaters Source: Nielsen EDI By Julie Snider, USA TODAY Activity Overview: In this activity, you will create two box and whisker plots of the data in the USA TODAY Snapshot® "Super ticket sales." You will calculate mean, median and mode values for both sets of data. You will then compare the two sets of data by analyzing the differences graphically in the box and whisker plots, and numerically as percents of ticket sales. ©COPYRIGHT 2004 USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co., Inc. This activity was created for use with Texas Instruments handheld technology. MATH TODAY STUDENT EDITION Super Ticket Sales Conquering comic heroes LIFE SECTION - FRIDAY - APRIL 26, 2002 - PAGE 1D By Susan Wloszczyna USA TODAY Behind nearly every timeless comic- Man comic books the way an English generations weaned on cowls and book hero, there's a deceptively unas- scholar loves Macbeth," he confess- capes.