How Regions Adjust to Base Closings: the Case of Loring AFB Ten Years After Closure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M1:Litlqry Law Review

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY PAMPHLET 27-1 00-22 M1:LITLQRY LAW REVIEW GOVER?;\IEST C.41 SED IIEL.4TS I\ THE PERFORhIANCE OF FEDERXI, COSTRICT.5 THE I>IPr\CT OF THE COSTRACT CLAL‘S E 5 Ifajor Robert B. Clarke PL-BLIC POLICt- .4TD PHIV.ITE PEACE-THE FINALITY OF .4 JLDICI 4L DETER>IIS.ITION Caprain .li’attheu B. O’Donnell, Jr. THE DEVIL‘S ARTICLE Wing Commander D. R. .i’zchols IIILTT>iRY LA%- 13 SP.4IN Brigadier General Eduardo De IVO Louis THE IAK OF THE SF-4: A P.4RALLEL FOR SPACE LAW Captain lack H. Pilltanas FIVE -YE A R C KvIL LXT I V E IN DES PREFACE The Military Law Review is designed to provide a medium for those interested in the field of military law to share the product of their experience and research with their fellow lawyers. Articles should be of direct concern and import in this area of scholarship, and preference will be given to those articles having lasting value as reference material for the military lawyer. The Militury Law Review does not purport to promulgate De- partment of the Army policy or to be in any sense directory. The opinions reflected in each article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Judge Advocate General or the Department of the Army. Articles, comments, and notes should be submitted in duplicate, triple spaced, to the Editor, Military Law Review, The Judge Ad- vocate General’s School, U. s. Army, Charlottesville, Virginia. Footnotes should be triple spaced, set out on pages separate from the text and follow the manner of citation in the Harvurd Blue Book. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Economics of Logistic Support: an Analysis of Policy and the Cost and Pre Paredness Contributions of Premium Transport of Military Cargoes

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received. Mic 60-6379 JONES, Douglas Norin. ECONOMICS OF LOGISTIC SUPPORT: AN ANALYSIS OF POLICY AND THE COST AND PRE PAREDNESS CONTRIBUTIONS OF PREMIUM TRANSPORT OF MILITARY CARGOES. University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan JONES, Douglas Norin. Mic 60-6379 The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1960 Economics, commerce-business University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan ECONOMICS OF LOGISTIC SUPPORT t AN ANALYSIS OF POLICY AND THE COST AND PREPAREDNESS CONTRIBUTIONS OF PREMIUM TRANSPORT OF MILITARY CARGOES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University B y Douglas Norin Jones, B. A., M. A. * * * * * * * The Ohio State University 1960 Approved by: Adviser Department of Economics CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION . .......................... 1 A. The Setting ....... '.............. 1 B. The Hypotheses .......... 5 C. Scope, Method, and Sources .... 8 II. TIME AND LOGISTIC SUPPORT — A DERIVED RESPONSE TO THE MILITARY THREAT .... 12 A. The Image ............. 12 B. Time in Transport ............ 17 C. Defense Air Commitment Equation . 25 III. COST AND LOGISTIC SUPPORT ....... 27 A. Cost P r e s s u r e s ................... 27 B. Practice ................. 31 C. Implications .......... 42 IV. THE ORGANIZATION FOR TRANSPORT SUPPORT . 49 A. Philosophy and Goals ....... 49 B. Single Manager Concept and Assignments . * ............ 33 C. Practice .......... 61 V. THE BUNDING FOR TRANSPORT ....... 65 A. Concept and Application ........... 65 B* Practice and A p p r a i s a l ........... 75 VI. PUBLIC POLICY TOWARD THE MILITARY USE OF TRANSPORT RESOURCES ....... 80 A. Paradox in P o l i c y ................ -

Financial Statements for the Year Ended June 30, 2006

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) 2007 ANNUAL REPORT LO!R]9{{j Vt£o/ELOPJvft£fJ\[T .9LV.TJiO!RJPY 0 :r !Jvf.9U !l\Lf£ LORING COMMERCE CENTRE To the Citizens of the State of Maine: As set forth in our enabling legislation, the Loring Development Authority's (LDA) mission is to redevelop the Loring properties for the purpose of creating jobs and economic activity to replace the economic losses associated with Loring's closure. The Air Force left us with over three million square feet of building space in 150 major buildings ranging in size from 2,000 square feet to 194,000 square feet. Many of these buildings have gone back into use supporting new and different activities. As our development work began, the replacement of 1,100 civilian jobs lost when the Air Force left, became our first priority. Outlined below are examples of how former Air Force buildings have been reused in novel ways by businesses that together employ over 1,400 people. The Former Base Hospital. This 145,000 square foot state-of-the-art building was constructed in 1988 at a cost of$28 million and within months after Loring closed in 1994 it was occupied by the Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DF AS). DFAS is the newly created centralized accounting and processing center for the Department of Defense. -

94 Stat. 1782 Public Law 96-418—Oct

PUBLIC LAW 96-418—OCT. 10, 1980 94 STAT. 1749 Public Law 96-418 96th Congress An Act To authorize certain construction at military installations for fiscal year 1981, and Oct. 10, 1980 for other purposes. [H.R. 7301] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That this Act may be Military cited as the "MiUtary Construction Authorization Act, 1981". Au'thSdon Act, 1981. TITLE I—ARMY AUTHORIZED ARMY CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army may establish or develop military installations and facilities by acquiring, constructing, con verting, rehabilitating, or installing permanent or temporary public works, including land acquisition, site preparation, appurtenances, utilities, and equipment, for the following acquisition and construc tion: INSIDE THE UNITED STATES UNITED STATES ARMY FORCES COMMAND Fort Bragg, North Carolina, $16,350,000. Fort Campbell, Kentucky, $14,200,000. Fort Carson, Colorado, $129,960,000. Fort Devens, Massachusetts, $1,000,000. Fort Drum, New York, $5,900,000. Fort Gillem, Georgia, $2,600,000. Fort Hood, Texas, $24,420,000. Fort Hunter-Liggett, California, $5,100,000. Fort Lewis, Washington, $16,000,000. Fort Ord, California, $4,700,000. Fort Polk, Louisiana, $14,800,000. Fort Riley, Kansas, $890,000. Fort Sam Houston, Texas, $3,750,000. Fort Stewart/Hunter Army Air Field, Georgia, $31,700,000. Presidio of San Francisco, California, $750,000. UNITED STATES ARMY WESTERN COMMAND Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, $12,220,000. Tripler Army Medical Center, Hawaii, $84,500,000. UNITED STATES ARMY TRAINING AND DOCTRINE COMMAND Fort A. -

Public Law 85-325-Feb

72 ST AT. ] PUBLIC LAW 85-325-FEB. 12, 1958 11 Public Law 85-325 AN ACT February 12, 1958 To authorize the Secretary of the Air Force to establish and develop certain [H. R. 9739] installations for'the national security, and to confer certain authority on the Secretary of Defense, and for other purposes. Be it enacted Ify the Senate and House of Representatives of the Air Force instal United States of America in Congress assembled^ That the Secretary lations. of the Air Force may establish or develop military installations and facilities by acquiring, constructing, converting, rehabilitating, or installing permanent or temporary public works, including site prep aration, appurtenances, utilities, and equipment, for the following projects: Provided^ That with respect to the authorizations pertaining to the dispersal of the Strategic Air Command Forces, no authoriza tion for any individual location shall be utilized unless the Secretary of the Air Force or his designee has first obtained, from the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, approval of such location for dispersal purposes. SEMIAUTOMATIC GROUND ENVIRONMENT SYSTEM (SAGE) Grand Forks Air Force Base, Grand Forks, North Dakota: Admin Post, p. 659. istrative facilities, $270,000. K. I. Sawyer Airport, Marquette, Michigan: Administrative facili ties, $277,000. Larson Air Force Base, Moses Lake, Washington: Utilities, $50,000. Luke Air Force Base, Phoenix, Arizona: Operational and training facilities, and utilities, $11,582,000. Malmstrom Air Force Base, Great Falls, Montana: Operational and training facilities, and utilities, $6,901,000. Minot Air Force Base, Minot, North Dakota: Operational and training facilities, and utilities, $10,338,000. -

Before, During and After Sandy Air Mobility Forces Support Superstorm Sandy Relief Efforts Pages 8-13

AIRLIFT/TANKER QUARTERLY Volume 21 • Number 1 • Winter 2013 Before, During and After Sandy Air Mobility Forces Support Superstorm Sandy Relief Efforts Pages 8-13 In Review: 44th Annual A/TA Convention and the 2012 AMC and A/TA Air Mobility Symposium & Technology Exposition Pages 16-17 CONTENTS… Association News Chairman’s Comments ........................................................................2 President’s Message ...............................................................................3 Secretary’s Notes ...................................................................................3 Association Round-Up ..........................................................................4 AIRLIFT/TANKER QUARTERLY Volume 21 • Number 1 • Winter 2013 Cover Story Airlift/Tanker Quarterly is published four times a year by the Airlift/Tanker Association, Before, During and After Sandy 9312 Convento Terrace, Fairfax, Virginia 22031. Postage paid at Belleville, Illinois. Air Mobility Forces Support Superstorm Sandy Relief Efforts ...8-13 Subscription rate: $40.00 per year. Change of address requires four weeks notice. The Airlift/Tanker Association is a non-profit Features professional organization dedicated to providing a forum for people interested in improving the capability of U.S. air mobility forces. Membership CHANGES AT THE TOP in the Airlift/Tanker Association is $40 annually or $110 for three years. Full-time student Air Mobility Command and membership is $15 per year. Life membership is 18th Air Force Get New Commanders ..........................................6-7 $500. Industry Partner membership includes five individual memberships and is $1500 per year. Membership dues include a subscription to Airlift/ An Interview with Lt Gen Darren McDew, 18AF/CC ...............14-15 Tanker Quarterly, and are subject to change. by Colonel Greg Cook, USAF (Ret) Airlift/Tanker Quarterly is published for the use of subscribers, officers, advisors and members of the Airlift/Tanker Association. -

Transfer Agreement Between Us Air

BK3233PG 157 DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE SDMS DocID 260760 AIR FORCE BASE CONVERSION AGENCY 0011G4 Srpprfnnd Records Center svrE-.Jjt BREAK: OTHER: DEC 1 4 1998 AFBCA/DR 1700 North Moore Street, Suite 2300 Arlington, VA 22209-2802 Mr. Stanley A. Burger Chief, Division of Administrative Services Employment and Training Administration U.S. Department of Labor 200 Constitution Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20210 Dear Mr. Burger On April 6,1994, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) submitted a request for the transfer of eight (8) parcels referred to as Parcels B, and B-l through B-7, consisting of 42 acres and containing eleven (11) buildings located on Loring Air Force Base, for the establishment of a Job Corps Center. This property was part of the property at Loring that was declared excess to the needs of the Department of the Air Force on October 14,1991. Accordingly, pursuant to the Authority vested in the Secretary of the Air Force, acting under and pursuant to the FPASA of 1949, as amended, 40 U.S.C. § 471 et seq., and the delegation of authority to the Secretary of Defense from the Administrator of the General Services Administration, dated March 1, 1989, pursuant to Title II, Section 204, of Defense Authorization Amendments and Base Closure and Realignment Act, and in line with the Air Force Record of Decision (ROD) signed on April:! 1,1996, (Attachment 2), I hereby.transfer the above described property to the Secretary of Labor subject to the terms, conditions, reservations, and restrictions set forth below. In accordance with Section 4467(f)(l) of the National Defense Authorization Act for 1993, the transfer is at no cost; In compliance with CERCLA Section 120 (h) and in order to document the environmental condition of the property, a Basewide Environmental Baseline Survey (Basewide BBS) was prepared for Loring AFB, which is provided as Attachment 6, along with a Supplemental Environmental Baseline Survey (Supplemental BBS) as Attachment 4Kwhich address the property that is the subject of this transfer. -

State of Maine

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) LEGISLATIVE RECORD OF THE One Hundred And Fourteenth Legislature OF THE State Of Maine VOLUME V SECOND REGULAR SESSION March 20, 1990 to April 14, 1990 Index HOUSE & SENATE LEGISLATIVE SENTIMENTS December 7, 1988 to April 14, 1990 LEGISLATIVE SENTIMENTS OF THE One Hundred And Fourteenth Legislature OFTHE House of Representatives HOUSE LEGISLATIVE SENTIMENTS - DECEMBER 7, 1988 - DECEMBER 4, 1990 APPENDIX TO THE LEGISLATIVE RECORD Ray Lund and Jennifer Merry, art educators at 114TH MAINE LEGISLATURE Thornton Academy, whose art program has been selected by the National Art Education Association to receive the Program Standards Award for excellence in the The following expressions of Legislative area of art education; (HLS 15) Sentiment appeared in the House Calendar between December 7, 1988 and Apri 1 14, 1990 pursuant to Joi nt Rocco Deluca, of Thornton Academy, on being named Rule 34: (These sentiments are dated December 7, to the 1988 Telegram All-State Class A Second-team 1988, through December 4, 1990.) Defense Football Team; (HLS 16) Todd Mauri ce, of Thornton Academy, who has been Bob and Barbara Cormier, a well-liked couple in named to the 1988 All-State Telegram Class A First the Kennebec Vall ey, on the occas i on of thei r 35th team Offense Football Team; (HLS 17) wedding anniversary; (HLS 1) John Douzepis, of Thornton Academy, who has been University of Maine student Sharon M. -

The Impact of Base Redevelopment for New England Bernd F

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 5-2012 From Tank Trails to Technology Parks: the Impact of Base Redevelopment for New England Bernd F. Schliemann University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Schliemann, Bernd F., "From Tank Trails to Technology Parks: the Impact of Base Redevelopment for New England" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 594. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/594 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM TANK TRAILS TO TECHNOLOGY PARKS: THE IMPACT OF BASE REDEVELOPMENT FOR NEW ENGLAND A Dissertation Presented by BERND F. SCHLIEMANN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY MAY 2012 Regional Planning © Copyright by Bernd F. Schliemann 2012 All Rights Reserved FROM TANK TRAILS TO TECHNOLOGY PARKS: THE IMPACT OF BASE REDEVELOPMENT FOR NEW ENGLAND A Dissertation Presented by BERND F. SCHLIEMANN Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Henry C. Renski, Chair _______________________________________ John R. Mullin, Member _______________________________________ Michael A. Ash, Member ____________________________________ Elizabeth A. Brabec Department Head Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my beautiful wife Bianca for her endearing support of each of my professional and personal endeavors. -

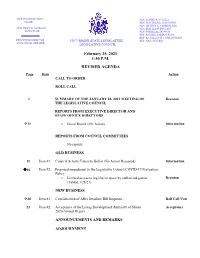

February 25, 2021 1:30 P.M. REVISED AGENDA Page Item Action CALL to ORDER

REP. RYAN FECTEAU SEN. ELOISE A. VITELLI CHAIR SEN. MATTHEA E. DAUGHTRY SEN. JEFFREY L. TIMBERLAKE SEN. TROY D. JACKSON SEN. MATTHEW POULIOT VICE-CHAIR REP. MICHELLE DUNPHY REP. RACHEL TALBOT ROSS REP. KATHLEEN R.J. DILLINGHAM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 130TH MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE REP. JOEL STETKIS SUZANNE M. GRESSER LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL February 25, 2021 1:30 P.M. REVISED AGENDA Page Item Action CALL TO ORDER ROLL CALL 1 SUMMARY OF THE JANUARY 28, 2021 MEETING OF Decision THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL REPORTS FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AND STAFF OFFICE DIRECTORS 11 • Fiscal Report (Mr. Nolan) Information REPORTS FROM COUNCIL COMMITTEES No reports OLD BUSINESS 15 Item #1: Council Actions Taken by Ballot (No Action Required) Information 16 Item #2: Proposed amendment to the Legislative Council COVID-19 Prevention Policy • Limited access to legislative space by authorized guests. Decision (Tabled 1/28/21) NEW BUSINESS 20 Item #1: Consideration of After Deadline Bill Requests Roll Call Vote 23 Item #2: Acceptance of the Loring Development Authority of Maine Acceptance 2020 Annual Report ANNOUNCEMENTS AND REMARKS ADJOURNMENT REP. RYAN FECTEAU SEN. NATHAN L. LIBBY CHAIR SEN. ELOISE A. VITELLI SEN. JEFFREY L. TIMBERLAKE SEN. TROY JACKSON SEN. MATTHEW POULIOT VICE-CHAIR REP. MICHELLE DUNPHY REP. RACHEL TALBOT ROSS REP. KATHLEEN R.J. DILLINGHAM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR REP. JOEL STETKIS SUZANNE M. GRESSER 130TH MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL MEETING SUMMARY January 28, 2021 CALL TO ORDER Speaker Fecteau called the January 28, 2021 -

LORING DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY of Lvlaine

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) 2014 ANNUAL REPORT LORING DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY OF lvlAINE 1.0" IN G DIVILO,MINT AUTHO,UTY 0' MAINI • LAW and LEGISLATNE Rt~FERENCE LIBRARY 43 STArE HOUSE STATION Paragraph 13080-L AUGUSTA, ME 04333-0043 Fiscal Year 2014 Annual Report July 1, 2013- June 30, 2014 Page Paragraph 1A: Description of the Authority's Operations .............................. 2 Paragraph 1B: Authority's Audited Financial Statements for the Year Ended June 30, 2014 .......................................... 9 Paragraph lC: Property Transactions ............................................................... lO Paragraph 1D: An accounting of all activities of any special utility ................ 11 district formed under Section 13080-G (None) Paragraph 1E: A listing of any property acquired by eminent domain.......... 11 under Section 13080-G (None) Paragraph 1F: A listing of any bonds issued (None) ...................................... 11 Paragraph 1G: Subsequent Events and Proposed Activities ............................ 12 Paragraph 1H: Further Actions Suitable for Achieving the Purposes ............ 15 of this Article Addendums: 1) Loring Development Authority Board of Trustees .......................................... 17 2) Loring Development