Computer Chess and Search

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spacewarduino

1 SPACEWARDUINO Kaivan Wadia (Department of EECS) – Massachusetts Institute of Technology Advisor: Prof. Philip Tan ABSTRACT Spacewar! was one of the first ever computer games developed in the early 1960s. Steve Russell, Martin Graetz and Wayne Witaenem of the fictitious "Hingham Institute" conceived of the game in 1961, with the intent of implementing it on a DEC PDP-1 computer at MIT. Alan Kotok obtained some sine and cosine routines from DEC following which Steve Russell started coding and the first version was produced by February 1962. Spacewar! was the first computer game written at MIT. In the duration of this project we hope to implement the same game on an Arduino Microcontroller with a Gameduino shield while examining the original assembly code and staying as true to the original version of the game as possible. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. UNDERSTANDING THE SOURCE CODE 4 3. VECTOR GRAPHICS AND SPACESHIPS 7 4. SPACEWAR! NIGHT SKY 9 5. THE ARDUINO/GAMEDUINO IMPLEMENTATION 11 6. CONCLUSION 13 7. REFERENCES 14 3 1. INTRODUCTION The major aim of this project is to replicate the first computer game written at MIT, Spacewar!. In the process we aim to learn a lot about the way video games were written for the machines in the pioneering days of computing. Spacewar! is game of space combat created for the DEC PDP-1 by hackers at MIT, including Steve Russell, Martin Graetz, Wayne Witaenem, Alan Kotok, Dan Edwards, and Peter Samson. The game can be played on a Java emulator at http://spacewar.oversigma.com/. -

Virginia Chess Federation 2010 - #4

VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter The bimonthly publication of the Virginia Chess Federation 2010 - #4 -------- Inside... / + + + +\ Charlottesville Open /+ + + + \ Virginia Senior Championship / N L O O\ Tim Rogalski - King of the Open Sicilian 2010 State Championship announcement/+p+pO Op\ and more, including... / Pk+p+p+\ Larry Larkins revisits/+ + +p+ \ the Yeager-Perelshteyn ending/ + + + +\ /+ + + + \ ________ VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter 2010 - Issue #4 Editor: Circulation: Macon Shibut Ernie Schlich 8234 Citadel Place 1370 South Braden Crescent Vienna VA 22180 Norfolk VA 23502 [email protected] [email protected] k w r Virginia Chess is published six times per year by the Virginia Chess Federation. Membership benefits (dues: $10/yr adult; $5/yr junior under 18) include a subscription to Virginia Chess. Send material for publication to the editor. Send dues, address changes, etc to Circulation. The Virginia Chess Federation (VCF) is a non-profit organization for the use of its members. Dues for regular adult membership are $10/yr. Junior memberships are $5/yr. President: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, mhoffpauir@ aol.com Treasurer: Ernie Schlich, 1370 South Braden Crescent, Norfolk VA 23502, [email protected] Secretary: Helen Hinshaw, 3430 Musket Dr, Midlothian VA 23113, [email protected] Tournaments: Mike Atkins, PO Box 6138, Alexandria VA, [email protected] Scholastics Coordinator: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, [email protected] VCF Inc Directors: Helen Hinshaw (Chairman), Rob Getty, John Farrell, Mike Hoffpauir, Ernie Schlich. otjnwlkqbhrp 2010 - #4 1 otjnwlkqbhrp Charlottesville Open by David Long INTERNATIONAL MASTER OLADAPO ADU overpowered a field of 54 Iplayers to win the Charlottesville Open over the July 10-11 weekend. -

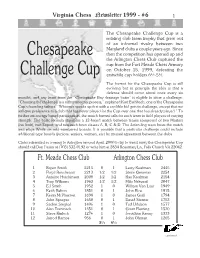

1999/6 Layout

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

100 Years of Shannon: Chess, Computing and Botvinik Iryna Andriyanova

100 Years of Shannon: Chess, Computing and Botvinik Iryna Andriyanova To cite this version: Iryna Andriyanova. 100 Years of Shannon: Chess, Computing and Botvinik. Doctoral. United States. 2016. cel-01709767 HAL Id: cel-01709767 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/cel-01709767 Submitted on 15 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CLAUDE E. SHANNON 1916—2001 • 1936 : Bachelor in EE and Mathematics from U.Michigan • 1937 : Master in EE from MIT • 1940 : PhD in EE from MIT • 1940 : Research fellow at Princeton • 1940-1956 : Researcher at Bell Labs • 1948 : “A Mathematical Theory of Communication”, Bell System Technical Journal • 1956-1978 : Professor at MIT 100 YEARS OF SHANNON SHANNON, BOTVINNIK AND COMPUTER CHESS Iryna Andriyanova ETIS Lab, UMR 8051, ENSEA/Université de Cergy-Pontoise/CNRS 54TH ALLERTON CONFERENCE SHORT HISTORY OF CHESS/COMPUTER CHESS CHESS AND COMPUTER CHESS TWO PARALLELS W. Steinitz M. Botvinnik A. Karpov 1886 1894 1921 1948 1963 1975 1985 2006* E. Lasker G. Kasparov W. Steinitz: simplicity and rationality E. Lasker: more risky play M. Botvinnik: complicated, very original positions A. Karpov, G. Kasparov: Botvinnik’s school CHESS AND COMPUTER CHESS TWO PARALLELS W. -

ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1.1 Eadweard Muybridge, Descending

APPENDIX: ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1.1 Eadweard Muybridge, Descending Stairs and Turning Around, photographs from series Animal Locomotion, 1884-1885. 236 237 Figure 1.2 Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 oil on canvas, 1912. Philadelphia Museum of Art. 238 Figure 1.3 Giacomo Balla, Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, oil on canvas, 1912. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. 239 Figure 1.4 A. Michael Noll, Gaussian Quadratic, computer-generated image, 1963. 240 Figure 1.5 Stephen Rusell with Peter Samson, Martin Graetz,Wayne Witanen, Alan Kotok, and Dan Edwards, Spacewar!, computer game, designed at MIT on DEC PDP-1 assembler, 1962. Above: view of screen. Below: console. 241 Figure 1.6 Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait, photograph of image created on Commodore Amiga 1000 computer using Graphicraft software, 1986. 242 Figure 1.7 Nam June Paik, Magnet TV, black and white television with magnet, 1965. 243 Figure 1.8 Nam June Paik, Zen for TV, black and white television, 1963-1975. 244 Figure 1.9 Vito Acconci, Centers, performance on video, 20 minutes, 1971. 245 Figure 1.10 Joan Jonas, Left Side, Right Side, performance on video, 1972. Pat Hearn Gallery, New York. 246 Figure 1.11 Dan Graham, Present Continuous Past, installation view, 1974. 247 Figure 1.12 Gary Hill, Hole in the Wall, installation at the Woodstock Artists Association, Woodstock, NY, 1974. 248 Figure 1.13 Nam June Paik, TV Buddha, mixed-media video sculpture, installed at Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1974. 249 Figure 2.1 jodi (Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans), wwwwwwwww.jodi.org, screenshot. -

Scenarios for Using the ARPANET at the International Conference On

VAlirc NIC 11863 SCENARIOS for using the ARPANET at the INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPUTER COMMUNICATION Washington, D.C. October 24—26, 1972 ARPA Network Information Center Stanford Research Institute Menlo Park, California 94025 , 11?>o - 3 £: 3c? - 16 $<}0-l!:}o 3 - & i 3o iW |{: 3 cp - 3 NIC 11863 SCENARIOS for using the ARPANET at the INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPUTER COMMUNICATION Washington, D.C. October 24—26, 1972 ARPA Network Information Center Stanford Research Institute Menlo Park, California 94025 SCENARIOS FOR USING THE ARPANET AT THE ICCC We intend that the following scenarios be used by individuals to browse the ARPA Computer Network (ARPANET) in its current early stage of development and thereby to introduce themselves to some possibilities in computer communication. The scenarios include only a few of the existing ARPANET resources. They were chosen for this booklet (somewhat haphazardly) to exhibit variety and sophistication, while retaining simplicity. The scenarios are by no means complete or perfect. We have tried to make them accurate, but are certain that they contain errors. The scenarios are, therefore, only one kind of tool for experiencing computer communication. We assume that you will attend the various showings of film and videotape, pay close attention at the several scheduled demonstrations of specific resources, approach the ARPANET aggressively yourself using these scenarios, and unhesitatingly call upon the ICCC Special Project People for the advice and encouragement you are sure to need. The account numbers and passwords provided in these scenarios were generated spe cifically for the ICCC. It is hoped that some of them will remain available after the ICCC for continued browsing. -

Virginia Chess Federation 2008 - #6

VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter The bimonthly publication of the Virginia Chess Federation 2008 - #6 Grandmaster Larry Kaufman See page 1 VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter 2008 - Issue #6 Editor: Circulation: Macon Shibut Ernie Schlich 8234 Citadel Place 1370 South Braden Crescent Vienna VA 22180 Norfolk VA 23502 [email protected] [email protected] k w r Virginia Chess is published six times per year by the Virginia Chess Federation. Membership benefits (dues: $10/yr adult; $5/yr junior under 18) include a subscription to Virginia Chess. Send material for publication to the editor. Send dues, address changes, etc to Circulation. The Virginia Chess Federation (VCF) is a non-profit organization for the use of its members. Dues for regular adult membership are $10/yr. Junior memberships are $5/yr. President: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, mhoffpauir@ aol.com Treasurer: Ernie Schlich, 1370 South Braden Crescent, Norfolk VA 23502, [email protected] Secretary: Helen Hinshaw, 3430 Musket Dr, Midlothian VA 23113, jallenhinshaw@comcast. net Scholastics Coordinator: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, [email protected] VCF Inc. Directors: Helen Hinshaw (Chairman), Rob Getty, John Farrell, Mike Hoffpauir, Ernie Schlich. otjnwlkqbhrp 2008 - #6 1 otjnwlkqbhrp Larry Kaufman, of Maryland, is a familiar face at Virginia tournaments. Among others he won the Virginia Open in 1969, 1998, 2000, 2006 and 2007! Recently Larry achieved a lifelong goal by attaining the title of International Grandmaster, and agreed to tell VIRGINIA CHESS readers how it happened. -ed World Senior Chess Championship by Larry Kaufman URING THE LAST FIVE YEARS OR SO, whenever someone asked me Dif I still hoped to become a GM, I would reply something like this: “I’m too old now to try to do it the normal way, but perhaps when I reach 60 I will try to win the World Senior, which carries an automatic GM title. -

Robert Alan Saunders

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LEMELSON CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF INVENTION AND INNOVATION Robert Alan Saunders Transcript of an interview conducted by Christopher Weaver at National Museum of American History Washington, D.C., USA on 29 November 2018 with subsequent additions and corrections For additional information, contact the Archives Center at 202-633-3270 or [email protected] All uses of this manuscript are covered by an agreement between the Smithsonian Institution and Robert Alan Saunders dated November 29, 2018. For additional information about rights and reproductions, please contact: Archives Center National Museum of American History Smithsonian Institution MRC 601 P.O. Box 37012 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 Phone: 202-633-3270 TDD: 202-357-1729 Email: [email protected] Web: http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives/rights-and-reproductions Preferred citation: Robert Alan Saunders, “Interview with Robert Alan Saunders,” conducted by Christopher Weaver, November 29, 2018, Video Game Pioneers Oral History Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Acknowledgement: The Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Entertainment Software Association and Coastal Bridge Advisors for this oral history project. For additional information, contact the Archives Center at 202-633-3270 or [email protected] Abstract Robert Saunders begins discussing his early family life, education, and early exposure to electrical engineering. He next recounts his time at MIT, recalling members of the Tech Model Railroad Club and his work with the TX-0 and PDP-1 computers. Saunders discusses the contributions of Spacewar! team members to the project and his development of the original PDP-1 game controllers. -

Chapter 15, New Pieces

Chapter 15 New pieces (2) : Pieces with limited range [This chapter covers pieces whose range of movement is limited, in the same way that the moves of the king and knight are limited in orthochess.] 15.1 Pieces which can move only one square [The only such piece in orthochess is the king, but the ‘wazir’ (one square orthogonally in any direction), ‘fers’ or ‘firzan’ (one square diagonally in any direction), ‘gold general’ (as wazir and also one square diagonally forward), and ‘silver general’ (as fers and also one square orthogonally forward), have been widely used and will be found in many of the games in the chapters devoted to historical and regional versions of chess. Some other flavours will be found below. In general, games which involve both a one-square mover and ‘something more powerful’ will be found in the section devoted to ‘something more powerful’, but the two later developments of ‘Le Jeu de la Guerre’ are included in this first section for convenience. One-square movers are slow and may seem to be weak, but even the lowly fers can be a potent attacking weapon. ‘Knight for two pawns’ is rarely a good swap, but ‘fers for two pawns’ is a different matter, and a sound tactic, when unobservant defence permits it, is to use the piece with a fers move to smash a hole in the enemy pawn structure so that other men can pour through. In xiangqi (Chinese chess) this piece is confined to a defensive role by the rules of the game, but to restrict it to such a role in other forms of chess may well be a losing strategy.] Le Jeu de la Guerre [M.M.] (‘M.M.’, ranks 1/11, CaHDCuGCaGCuDHCa on ranks perhaps J. -

Computer Chess Methods

COMPUTER CHESS METHODS T.A. Marsland Computing Science Department, University of Alberta, EDMONTON, Canada T6G 2H1 ABSTRACT Article prepared for the ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, S. Shapiro (editor), D. Eckroth (Managing Editor) to be published by John Wiley, 1987. Final draft; DO NOT REPRODUCE OR CIRCULATE. This copy is for review only. Please do not cite or copy. Acknowledgements Don Beal of London, Jaap van den Herik of Amsterdam and Hermann Kaindl of Vienna provided helpful responses to my request for de®nitions of technical terms. They and Peter Frey of Evanston also read and offered constructive criticism of the ®rst draft, thus helping improve the basic organization of the work. In addition, my many friends and colleagues, too numerous to mention individually, offered perceptive observations. To all these people, and to Ken Thompson for typesetting the chess diagrams, I offer my sincere thanks. The experimental work to support results in this article was possible through Canadian Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Grant A7902. December 15, 1990 COMPUTER CHESS METHODS T.A. Marsland Computing Science Department, University of Alberta, EDMONTON, Canada T6G 2H1 1. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Of the early chess-playing machines the best known was exhibited by Baron von Kempelen of Vienna in 1769. Like its relations it was a conjurer's box and a grand hoax [1, 2]. In contrast, about 1890 a Spanish engineer, Torres y Quevedo, designed a true mechanical player for king-and-rook against king endgames. A later version of that machine was displayed at the Paris Exhibition of 1914 and now resides in a museum at Madrid's Polytechnic University [2]. -

Alan Kotok & David R.R. Webber

JAi^ E F! N E T: ALAN KOTOK & DAVID R.R. WEBBER www.newriders.cirm 201 West 103rd Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46290 ~ — An Imprint of Pearson Education . Boston • Indianapolis • London • Munich • New York • San Francisco vi ebXML: The New Global Standard for Doing Business over the Internet Table of Contents PART I Executive Overview of ebXML 1 There's No Business Like E-Business 3 In Case You Hadn't Noticed, Doing Business Is Different Now 6 Business Isn't So Simple Anymore 11 From Just-in-Case to Just-in-Time Inventories 16 Investors Want to See Your Internet Strategy 22 Higher Volumes, Larger Scale, Bigger Numbers 23 Can Your Company's Systems Keep Pace? 26 Direct to Consumer 28 Disintermediation 28 Business to Business 29 Distributors 29 References and Affiliates 29 Muki-Vendor Malls 30 Standardizing Information Systems 30 Electronic Data Interchange (EDI): E-Business as We (Used to) Know It 31 Aim to Improve the Business Process 40 Sweat the Details 40 Aim for Interoperability 40 Link to Other Technologies 41 Endnotes 42 2 ebXML in a Nutshell 47 Vision and Scope 47 Software Processes, Puzzles, and Pyramids 49 ebXML Process Flow ,• 53 A Look at the ebXML Technical Architecture 55 Business Processes and Objects 57 Core Components 58 Trading Partner Profiles and Agreements 62 Registries and Repositories 64 Messaging Functions 68 Messaging Specifications 69 ebXML Message Package 69 Reliable Message Flow 11 Getting Started with ebXML 71 Endnotes 74 Table of Contents vii 3 ebXML at Work 77 Case 1: Go-Go Travel, in Search of a New Business -

The Real Inventors of Arcade Videogames Copy

1. The “real” Inventors of Arcade Videogames? As more and more of the early history of videogames comes to light, perceptions of who did what and when keep changing. For example: In a recent paper written by Professor Henry Lowood (Curator for History of Science & Technology Collections; Germanic Collections; Film & Media Collections, Stanford University) entitled “Meditations about Pong from different perspectives”, he reminds us of the story of the summer project of a “recently” (1970) graduated SAIL (Stanford University) student, Bill Pitts, and his friend, Hugh Tuck, as follows: “ The Galaxy Game was a coin-operated computer game for the newly released PDP 11/20, DEC's first 16-bit computer. DEC had fit the PDP 11 into a relatively small box and listed it for a mere $20,000, hoping thereby to open "new markets and new applications." Pitts and Tuck formed a company called Computer Recreations, bought the low-end version of the PDP-11 for only $13,000 and converted the PDP-10 version Spacewar! for this machine, including a Hewlett-Packard vector display, wooden cabinet, and other parts, their expenses came to roughly $20,000. In September 1971, they installed it in Stanford’s student union, where a later version that supported up to four monitors (eight players) could be found until 1979. The Galaxy Game was faithful not only to Spacewar!, but also to the player community (university students and computer engineers) and technical configuration (software code, vector displays, timesharing, etc.) that produced it” Is this not still another story describing the invention of the arcade videogame? So who was really “first”...as if it mattered if they did it independently.