Singers of Songs, Weavers of Dreams” by David Baker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

94 DOWNBEAT JUNE 2019 42Nd ANNUAL

94 DOWNBEAT JUNE 2019 42nd ANNUAL JUNE 2019 DOWNBEAT 95 JeJenna McLean, from the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, is the Graduate College Wininner in the Vocal Jazz Soloist category. She is also the recipient of an Outstanding Arrangement honor. 42nd Student Music Awards WELCOME TO THE 42nd ANNUAL DOWNBEAT STUDENT MUSIC AWARDS The UNT Jazz Singers from the University of North Texas in Denton are a winner in the Graduate College division of the Large Vocal Jazz Ensemble category. WELCOME TO THE FUTURE. WE’RE PROUD after year. (The same is true for certain junior to present the results of the 42nd Annual high schools, high schools and after-school DownBeat Student Music Awards (SMAs). In programs.) Such sustained success cannot be this section of the magazine, you will read the attributed to the work of one visionary pro- 102 | JAZZ INSTRUMENTAL SOLOIST names and see the photos of some of the finest gram director or one great teacher. Ongoing young musicians on the planet. success on this scale results from the collec- 108 | LARGE JAZZ ENSEMBLE Some of these youngsters are on the path tive efforts of faculty members who perpetu- to becoming the jazz stars and/or jazz edu- ally nurture a culture of excellence. 116 | VOCAL JAZZ SOLOIST cators of tomorrow. (New music I’m cur- DownBeat reached out to Dana Landry, rently enjoying includes the 2019 albums by director of jazz studies at the University of 124 | BLUES/POP/ROCK GROUP Norah Jones, Brad Mehldau, Chris Potter and Northern Colorado, to inquire about the keys 132 | JAZZ ARRANGEMENT Kendrick Scott—all former SMA competitors.) to building an atmosphere of excellence. -

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Jazz History and Research Graduate Program in Arts written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and Dr. Henry Martin And approved by Newark, New Jersey May 2016 ©2016 Zachary Streeter ALL RIGHT RESERVED ABSTRACT Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zach Streeter Thesis Director: Dr. Lewis Porter Despite the institutionalization of jazz music, and the large output of academic activity surrounding the music’s history, one is hard pressed to discover any information on the late jazz guitarist Jimmy Raney or the legacy Jimmy Raney left on the instrument. Guitar, often times, in the history of jazz has been regulated to the role of the rhythm section, if the guitar is involved at all. While the scope of the guitar throughout the history of jazz is not the subject matter of this thesis, the aim is to present, or bring to light Jimmy Raney, a jazz guitarist who I believe, while not the first, may have been among the first to pioneer and challenge these conventions. I have researched Jimmy Raney’s background, and interviewed two people who knew Jimmy Raney: his son, Jon Raney, and record producer Don Schlitten. These two individuals provide a beneficial contrast as one knew Jimmy Raney quite personally, and the other knew Jimmy Raney from a business perspective, creating a greater frame of reference when attempting to piece together Jimmy Raney. -

Cedille Records CDR 90000 066 DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 066 AFRICAN HERITAGE SYMPHONIC SERIES • VOLUME III WORLD PREMIERE RECORDINGS 1 MICHAEL ABELS (B

Cedille Records CDR 90000 066 DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 066 AFRICAN HERITAGE SYMPHONIC SERIES • VOLUME III WORLD PREMIERE RECORDINGS 1 MICHAEL ABELS (b. 1962): Global Warming (1990) (8:18) DAVID BAKER (b. 1931): Cello Concerto (1975) (19:56) 2 I. Fast (6:22) 3 II. Slow à la recitative (7:17) 4 III. Fast (6:09) Katinka Kleijn, cello soloist 5 WILLIAM BANFIELD (b. 1961): Essay for Orchestra (1994) (10:33) COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON (b. 1932) Generations: Sinfonietta No. 2 for Strings (1996) (19:31) 6 I. Misterioso — Allegro (6:13) 8 III. Alla Burletta (2:04) 7 II. Alla sarabande (5:35) 9 IV. Allegro vivace (5:28) CHICAGO SINFONIETTA / PAUL FREEMAN, CONDUCTOR TT: (58:45) Sara Lee Foundation is the exclusive corporate sponsor for African Heritage Symphonic Series, Volume III This recording is also made possible in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts & The Aaron Copland Fund for Music Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are supported in part by contributions and grants from individuals, foundations, corporations, and government agencies including the Alpha- wood Foundation, the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs (CityArts III Grant), and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. DDD Absolutely Digital™ CDR 90000 066 PROGRAM NOTES by dominique-rené de lerma The quartet of composers represented here have a par- cultures, and decided to write a piece that celebrates ticular distinction in common: Each displays remarkable these common threads as well as the sudden improve- stylistic versatility, working not just in concert idioms, but ment in international relations that was occurring.” The also in film music, gospel music, and jazz. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic “When Johnny Cash comes on the radio, no one changes the station. It’s a voice, a name with a soul that cuts across all boundaries and it’s a voice we all believe. Yours is a voice that speaks for the saints and the sinners – it’s like branch water for the soul. Long may you sing out. Loud.” – Tom Waits audio int‘l p. o. box 560 229 60407 frankfurt/m. germany www.audio-intl.com Catalog: IMP 6008 Format: 180-gram LP tel: 49-69-503570 mobile: 49-170-8565465 Available Spring 2011 fax: 49-69-504733 To order/preorder, please contact your favorite audiophile dealer. Jennifer Warnes, Famous Blue Raincoat. Shout-Cisco (three 200g 45rpm LPs). Joan Baez, In Concert. Vanguard-Cisco (180g LP). The 20th Anniversary reissue of Warnes’ stunning Now-iconic performances, recorded live at college renditions from the songbook of Leonard Cohen. concerts throughout 1961-62. The Cisco 45 rpm LPs define the state of the art in vinyl playback. Holly Cole, Temptation. Classic Records (LP). The distinctive Canadian songstress and her loyal Jennifer Warnes, The Hunter. combo in smoky, jazz-fired takes on the songs of Private-Cisco (200g LP). Tom Waits. Warnes’ post-Famous Blue Raincoat release that also showcases her own vivid songwriting talents in an Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Déjá Vu. exquisite performance and recording. Atlantic-Classic (200g LP). A classic: Great songs, great performances, Doc Watson, Home Again. Vanguard-Cisco great sound. The best country guitar-picker of his day plays folk ballads, bluegrass, and gospel classics. -

Dave Burrell, Pianist Composer Arranger Recordings As Leader from 1966 to Present Compiled by Monika Larsson

Dave Burrell, Pianist Composer Arranger Recordings as Leader From 1966 to present Compiled by Monika Larsson. All Rights Reserved (2017) Please Note: Duplication of this document is not permitted without authorization. HIGH Dave Burrell, leader, piano Norris Jones, bass Bobby Kapp, drums, side 1 and 2: b Sunny Murray, drums, side 2: a Pharoah Sanders, tambourine, side . Recording dates: February 6, 1968 and September 6, 1968, New York City, New York. Produced By: Alan Douglas. Douglas, USA #SD798, 1968-LP Side 1:West Side Story (L. Bernstein) 19:35 Side 2: a. East Side Colors (D. Burrell) 15:15 b. Margy Pargy (D. Burrell 2:58 HIGH TWO Dave Burrell, leader, arranger, piano Norris Jones, bass Sunny Murray, drums, side 1 Bobby Kapp, drums side 2. Recording Dates: February 6 and September 9, 1968, New York City, New York. Produced By: Alan Douglas. Additional production: Michael Cuscuna. Trio Freedom, Japan #PA6077 1969-LP. Side: 1: East Side Colors (D. Burrell) 15:15 Side: 2: Theme Stream Medley (D.Burrell) 15:23 a.Dave Blue b.Bittersweet Reminiscence c.Bobby and Si d.Margie Pargie (A.M. Rag) e.Oozi Oozi f.Inside Ouch Re-issues: High Two - Freedom, Japan TKCB-70327 CD Lions Abroad - Black Lion, UK Vol. 2: Piano Trios. # BLCD 7621-2 2-1996CD HIGH WON HIGH TWO Dave Burrell, leader, arranger, piano Sirone (Norris Jones) bass Bobby Kapp, drums, side 1, 2 and 4 Sunny Murray, drums, side 3 Pharoah Sanders, tambourine, side 1, 2, 4. Recording dates: February 6, 1968 and September 6, 1968, New York City, New York. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

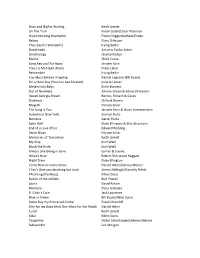

Days and Nights Waiting Keith Jarrett on the Trail Ferde Grofe/Oscar

Days and Nights Waiting Keith Jarrett On The Trail Ferde Grofe/Oscar Peterson Good Morning Heartache Fisher/Higgenbotham/Drake Bebop Dizzy Gillespie They Say It's Wonderful Irving Berlin Desafinado Antonio Carlos Jobim Ornithology Charlie Parker Matrix Chick Corea Long Ago and Far Away Jerome Kern Yours is My Heart Alone Franz Lehar Remember Irving Berlin You Must Believe in Spring Michel Legrand (Bill Evans) On a Clear Day (You Can See Forever) Lane & Lerner Melancholy Baby Ernie Burnett Out of Nowhere Johnny Green & Edward Heyman Sweet Georgia Brown Bernie, Finkard & Casey Daahoud Clifford Brown Mayreh Horace Silver The Song is You Jerome Kern & Oscar Hammerstein Autumn in New York Vernon Duke Nemesis Aaron Parks Satin Doll Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn End of a Love Affair Edward Redding Senor Blues Horace Silver Memories of Tomorrow Keith Jarrett My Ship Kurt Weill Mack the Knife Kurt Weill Almost Like Being in Love Lerner & Loewe What's New Robert Sherwood Haggart Night Train Duke Ellington Come Rain or Come Shine Harold Arlen/Johnny Mercer I Can't Give you Anything but Love Jimmy McHugh/Dorothy Fields Pfrancing (No Blues) Miles Davis Dance of the Infidels Bud Powell Laura David Raksin Manteca Dizzy Gillespie If I Didn't Care Jack Lawrence Blue in Green Bill Evans/Miles Davis Some Day my Prince will Come Frank Churchill One for my Baby (And One More for the Road) Harold Arlen Coral Keith Jarrett Solar Miles Davis Tangerine Victor Schertzinger/Johnny Mercer Sidewinder Lee Morgan Dexterity Charlie Parker Cantaloupe Island Herbie -

Rachel Barker and Alison Bracker

Tate Papers - Beuys is Dead: Long Live Beuys! Characterising Volition,... http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/05autumn/barker.htm ISSN 1753-9854 TATE’S ONLINE RESEARCH JOURNAL Beuys is Dead: Long Live Beuys! Characterising Volition, Longevity, and Decision-Making in the Work of Joseph Beuys Rachel Barker and Alison Bracker Fig.1 Joseph Beuys Felt Suit 1970 (photographed on acquisition, 1981) Felt Edition 27, no. 45 Tate Archive. Purchased by Tate 1981, de-accessioned 1995 © DACS 2005 View in Tate Collection For over four decades, artists have used organic or fugitive materials in order to instigate and interrogate processes of stasis, action, permanence, and mortality. Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), along with his contemporary, Dieter Roth (1930 –1998), pioneered this practice, probing concepts of energy, warmth, and transformation through the intelligent use of organic materials such as fat. But unlike Roth, who consistently advocated the unconstrained decomposition of his work, Beuys’ position on decay, change, and damage varied from statement to statement, and from piece to piece. As one conservator familiar with the artist’s work noted, in order to understand Beuys’ personal philosophy regarding conservation, ‘it would be necessary to read all his interviews and statements ... and even after this, one still might be restricted to speculation as to what he ... meant in this special case.’1 Unsurprisingly, museums housing Beuys sculptures and installations generally lack consistent counsel from the artist pertaining to preventive conservation, intervention, and restoration of his work. Together with codified conservation principles, artists’ statements and documentation (ideally, recorded at the time of acquisition, and at vital points in the work’s lifespan) greatly inform conservation decision- making. -

VJM 189 Hugo Van Der Laan

103 Early Blues/ In the Mornin', Session 10-006 E+ 104 Policy Blues/ I don't Know, Session 10-014 E- looks E+ but spots of light swish Hugo van der Laan 105 The Mississippi Mudder Sweet Jelly Rollin' Baker Man, De 7207 EE+/E 106 Alice Moore Too Many Men/ Don't Deny Me Baby Decca 7369 E- Van Beuningenstraat 53 D 107 Hand in Hand Women/ Doggin' Man Blues Decca 7380 EE+ 2582 KK Den Haag 108 Red Nelson Black Gal Stomp/ Jailhouse Blues the Netherlands BB 7918 E/EE+ 109 Joe Pullum Black Gal No. 4/ Robert Cooper, West Dallas Drag No. 2, buff Bluebird 5947 E- [email protected] light label damage sA/ large lipstick trace sB 105 J.H. Shayne Mr Freddy's Rag/ Chestnut Street Boogie Circle 1011 E-E 106 Pine Top Smith Brunswick album B-1102 E- Pinetop's Blues/ Boogie Woogie, Br 80008 E- Piano Blues 78’s for auction. Packing and air mail is 15 Euro, anywhere, for any I'm Sober Now/ Jump steady Blues amount of records. Payments by Eurotransfer, Bank transfer and Paypal. Br 80009 E- second masters Grading is aural, how they play with a ‘0028 stylus. E+ is the highest grade. 106 Speckled Red with Mandoline, Guitar, Try Me One More Time/ Louise Baltimore Blues, BB 8012E+ 107 Johnny Temple New Vicksburg Blues/ Louise Louise Blues 100 Albert Ammons' Rhytm Kings, Jammin' the Boogie/ Bottom Blues Decca 7244 E-/V+E- pdig restored audible 5' 12" Commodore 1516 E 108 Jinks Lee Blues/ Sundown Blues, BB 8913 E- 101 Leroy Carr with Scrapper Blackwell, My Woman's Gone Wrong/ looks V I Ain't Got No Money Now, Vo 02950 E- 106 Hociel Thomas with Mutt Carey sA, Go Down -

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2012 Studio Magazine Board of Trustees This Issue of Studio Is Underwritten, Editor-In-Chief Raymond J

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2012 Studio Magazine Board Of Trustees This issue of Studio is underwritten, Editor-in-Chief Raymond J. McGuire, Chairman in part, with support from Bloomberg Elizabeth Gwinn Carol Sutton Lewis, Vice-Chair Creative Director Rodney M. Miller, Treasurer The Studio Museum in Harlem is supported, Thelma Golden in part, with public funds provided by Teri Trotter, Secretary Managing Editor the following government agencies and elected representatives: Dominic Hackley Jacqueline L. Bradley Valentino D. Carlotti Contributing Editors The New York City Department of Kathryn C. Chenault Lauren Haynes, Thomas J. Lax, Cultural A"airs; New York State Council Joan Davidson Naima J. Keith on the Arts, a state agency; National Gordon J. Davis Endowment for the Arts; Assemblyman Copy Editor Reginald E. Davis Keith L. T. Wright, 70th A.D. ; The City Samir Patel Susan Fales-Hill of New York; Council Member Inez E. Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Dickens, 9th Council District, Speaker Design Sandra Grymes Christine Quinn and the New York City Pentagram Joyce K. Haupt Council; and Manhattan Borough Printing Arthur J. Humphrey, Jr. President Scott M. Stringer. Finlay Printing George L. Knox !inlay.com Nancy L. Lane Dr. Michael L. Lomax The Studio Museum in Harlem is deeply Original Design Concept Tracy Maitland grateful to the following institutional 2X4, Inc. Dr. Amelia Ogunlesi donors for their leadership support: Corine Pettey Studio is published two times a year Bloomberg Philanthropies Ann Tenenbaum by The Studio Museum in Harlem, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation John T. Thompson 144 W. 125th St., New York, NY 10027.