Lhasa, the Open City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTEMPORARY CHINA: a BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R Margins 0.9") by Lynn White

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R margins 0.9") by Lynn White This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of the seminars WWS 576a/Pol. 536 on "Chinese Development" and Pol. 535 on "Chinese Politics," as well as the undergraduate lecture course, Pol. 362; --to provide graduate students with a list that can help their study for comprehensive exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not too much should be made of this, because some such books may be too old for students' purposes or the subjects may not be central to present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan. Students with specific research topics should definitely meet Laird Klingler, who is WWS Librarian and the world's most constructive wizard. This list cannot cover articles, but computer databases can. Rosemary Little and Mary George at Firestone are also enormously helpful. Especially for materials in Chinese, so is Martin Heijdra in Gest Library (Palmer Hall; enter up the staircase near the "hyphen" with Jones Hall). Other local resources are at institutes run by Chen Yizi and Liu Binyan (for current numbers, ask at EAS, 8-4276). Professional bibliographers are the most neglected major academic resource at Princeton. -

Oppression, Dialogue, Body and Emotion – Reading a Many-Splendoured Thing

Linköping university - Department of Culture and Society (IKOS) Master´s Thesis, 30 Credits – MA in Ethnic and Migration Studies (EMS) ISRN: LiU-IKOS/EMS-A--21/02--SE Oppression, Dialogue, Body and Emotion – Reading A Many-Splendoured Thing Yulin Jin Supervisor: Stefan Jonsson Table of Contents 1.Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 1.1 Background……………………………………………………………………………………1 1.2 Research significance and research questions…………………………………………………4 1.3 Literature review………………………………………………………………………………4 1.3.1 Western research on Han Suyin’s life and works and A Many-Splendoured Thing……….5 1.3.2 Domestic research on Han Suyin’s life and works……………………………………….5 1.3.3 Domestic research on A Many-Splendoured Thing……………………………………………7 1.4 Research methods…………………………………………………………………………….9 1.5 Theoretical framework……………………………………………………………………….10 1.5.1 Identity process theory…………………………………………………….……………10 1.5.2 Intersectional theory and multilayered theory …………………………….……………10 1.5.3 Hybridity and the third space theory…………………………………………………….11 1.5.4 Polyphony theory………………………………………………………………………..11 1.5.5 Femininity and admittance………………………………………………………………12 1.5.6 Spatial theories…………………………………………………………………………..13 1.5.7 Body phenomenology……………………………………………………………………14 1.5.8 Hierarchy of needs……………………………………………………………………….15 2. Racial Angle……………………………………………………………………..16 2.1 Economic and emotional oppression…………………………………………………………16 2.2 Eurasian voices and native Chinese consciousnesses……………….………………………20 2.3 Personal solution……………………………………………………….……………………23 2.4 Cultural -

The Non-Western World: an Annotated Pibliograrhy for Flementary and Secondary 'Rchools

DOCIIMENT RESTIME ED 047 039 UD 011 172 AUTHOR Probandt, Puth TITLE The Non-Western World: An Annotated Pibliograrhy for Flementary and Secondary 'Rchools. INSTITIPION Massachusetts Univ., Amherst. School of rducatior. PUP FATF, May /0 NOTE g9P. AVAILABLE FFO!,! Center for International Tducation, School oc rlucation, University of Massachusets, Amherst, Mass. 01002 ($1.00) 'TOPS PRIC7 7:4RS Price MT-$.0.55 Fc-$1.20 DFSCRIPTORS African Culture, African History, African tit?rature, *AnnoiAtel Bibliographies, *Asian History, Elementary School Students, 1.atin American Culture, *Non Westerr Civilization, Resource Materials, Secondary School Students, *Social Stvaies, Spanish Culture ?lack Africa, China, India, Japan, Mexico, south America, Southeast Asia, Vietnam ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography on Asia, Africa, and Latin America contains sources primarily for elementary and secondary school students; also included are hooks for libraries and teachers. The bibliography on Asia is divided into curriculum materials and information bcoks. Some of the countries covered are: Burma; Cambodia; China; India; Japan; Korea; and Vietnam. The section on Black Africa includes a social studies curriculum for secondary students. The books on Iatin America cover Mexico as ve71. Appended are lists of audio-visual ail companies ani book publishers. (CV) S DEPARTMENT 0f NE A-TH. EDUCATION S WELFARE. OFFICE Of EDUCATION prN TNiS DOCUMENT NAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVES FROM TN E PERSON CS ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT POiNTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED 00 NOT NECES SARILV REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF ECU CATION POSITION OR POLICY THE NON-WESTERN WORLD AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY for ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS by Ruth Probandt CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION SCHOOL OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS Published May 1970 Copies may be obtained from the Center for International Education, School of Education, University of Katiew3husette, Amherst, Massachusetts 01002. -

"Thought Reform" in China| Political Education for Political Change

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1979 "Thought reform" in China| Political education for political change Mary Herak The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Herak, Mary, ""Thought reform" in China| Political education for political change" (1979). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1449. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1449 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUB SISTS, ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE: 19 7 9 "THOUGHT REFORM" IN CHINA: POLITICAL EDUCATION FOR POLITICAL CHANGE By Mary HeraJc B.A. University of Montana, 1972 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OP MONTANA 1979 Approved by: Graduat e **#cho o1 /- 7^ Date UMI Number: EP34293 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

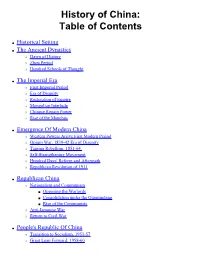

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

Epistemological Checkpoint: Reading Fiction As a Translation of History1

Postcolonial Text, Vol 9, No 1 (2014) Epistemological Checkpoint: Reading Fiction as a Translation of History1 Fiona Lee National University of Singapore, Asia Research Institute The Malayan Emergency, a war between the British colonial government and the communists, is cited as a rare model of success in the 2007 Counterinsurgency Field Manual published by the United States Army and Marine Corps (Dixon). During the Emergency, which lasted from 1948 to 1960, the colonial government embarked on a large-scale forced resettlement program that displaced up to half a million rural dwellers, 85 percent of whom were ethnic Chinese, from the jungle periphery into heavily patrolled camps (Ramakrishna 126). Masterminded by the British General Sir Harold Briggs, the resettlement plan was designed to sever the contact between the guerrilla troops hiding in the interior jungles and their civilian support network, the Min Yuen or People’s Movement, on which the former relied for intelligence and food supplies. In addition, the British implemented a national registration system, issuing identity cards to anyone above the age of 12, to regulate civilian movement and weed out communists; food-restricted areas were also designated to curb civilians from smuggling food to the communists. Although initially beset with setbacks, the counter-insurgency eventually forced the communists’ retreat and facilitated the 1957 transition of power to a postcolonial government, helmed by the conservative National Alliance (Barisan Nasional) sympathetic to British economic interests. Described by the British High Commissioner, Sir Gerald Templer, as an effort at winning “hearts and minds,” the Emergency measures were effectively presented as a primarily political activity that appealed to the people’s emotions and reason, and required minimal military force to win the people’s loyalty to the government (qtd in Dixon 7). -

Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966 Xianmin Shen University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966 Xianmin Shen University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Shen, X.(2015). Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3190 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DESTINATION HONG KONG: NEGOTIATING LOCALITY IN HONG KONG NOVELS 1945-1966 by Xianmin Shen Bachelor of Arts Tsinghua University, 2007 Master of Philosophy of Arts Hong Kong Baptist University, 2010 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Jie Guo, Major Professor Michael Gibbs Hill, Committee Member Krista Van Fleit Hang, Committee Member Katherine Adams, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Xianmin Shen, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Several institutes and individuals have provided financial, physical, and academic supports that contributed to the completion of this dissertation. First the Department of Literatures, Languages, and Cultures at the University of South Carolina have supported this study by providing graduate assistantship. The Carroll T. and Edward B. Cantey, Jr. Bicentennial Fellowship in Liberal Arts and the Ceny Fellowship have also provided financial support for my research in Hong Kong in July 2013. -

Interracial Experience Across Colonial Hong Kong and Foreign Enclaves in China from the Late 1800S to the 1980S

Volume 14, Number 2 • Spring 2017 Erasure, Solidarity, Duplicity: Interracial Experience across Colonial Hong Kong and Foreign Enclaves in China from the late 1800s to the 1980s By Vicky Lee, Ph.D., Hong Kong Baptist University Abstract: How were Eurasians perceived and classified in Hong Kong and China during this hundred-year period? Blood admixture was only one of many ways: others included patrilineal descent, choice of family name, and socio-economic background. Family-imposed silence on one’s Eurasian background remained strong, and individual attempts to erase one’s Eurasian identity were common for survival reasons. It is no wonder that government authorities often had difficulty quantifying their Eurasian population. What experiences of erasure of Eurasianness were shared both collectively and individually? A strong sense of Eurasian solidarity was manifested in different forms, such as intermarriage and community cemeteries. Duplicity was another common element in their experience: Name-changing practices and submission to the new Japanese government during the Occupation sometimes rendered Eurasians suspect during and after wartime. Memoirs reflect the constant psychological harassment of Eurasians in patriotic Chinese schools during 1940s Peking and in Tsingdao, and Eurasians became frequent targets for criticism during the Maoist Era. Many Eurasians experienced psychological and physical torment as their very faces were evidence enough to subject them to criticism and punishments. Permalink: Citation: Lee, Vicky. “Erasure, Solidarity, Duplicity: usfca.edu/center-asia-pacific/perspectives/v14n2/Lee Interracial Experience across Colonial Hong Kong and Keywords: Foreign Enclaves in China from the late 1800s to the Chinese Eurasian, Mixed Identities, Colonial 1980s,” Asia Pacific Perspectives, Vol. -

Han Suyin Family Doctor, Author, and a Bridge Between China and the West

OBITUARIES Han Suyin Family doctor, author, and a bridge between China and the West Han Suyin, family doctor (b circa 1917, received a scholarship to continue studies q University of London 1948), died after in Brussels. Returning to China by ship in a lengthy illness at home in Lausanne, 1938, she met Tang Pao-Huang, a young Switzerland, on 2 November 2012. military officer aligned with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist party. They married in Wuhan days During the 1950s in Malaysia her patients before it fell to the Japanese military and fled addressed her as either Dr Chow, her Chinese with Chiang Kai-shek inland to Chongqing, surname, or as Dr Comber, her British where she worked as a midwife in a US husband’s surname. In literary circles and in missionary hospital. Hollywood she was known by the pen name Encouraged by a missionary doctor, she Han Suyin, author of the 1952 bestselling wrote the story of her perilous journeys with novel A Many-Splendoured Thing, adapted in Pao, which was published in 1942 as the 1955 into an Oscar winning tearjerker and love novel Destination Chungking. That same year story starring William Holden. she travelled with her husband to London, where he was posted as military attaché. When Novels and family medicine he moved on to Washington, she remained Despite her literary fame and financial success, in London with her daughter and resumed Han continued through the 1950s to practise medical training at the Royal Free Hospital. family medicine in the Malaysian city of Johor GERARDFOUET/AFP/GETTY IMAGES Pao died in 1947, fighting communist forces Bahru, part of the Singapore metropolitan in China. -

List of Total Books T.S.Chanakya

LIST OF BOOKS (T.S.CHANAKYA) Sr. No. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR 1 SOCIAL STUDIES VINCENT G HUTCHINSON 2 2001 A SPACE ODYSSEY ARTHUR CLARKE 3 A HISTORY OF INDIA - VOL -1 ROMILA THAPAR 4 TRANISISTOR AMPLIPHIERS FOR AUDIO FRIQUENCIES THOMAS RUDDEN 5 THE BOOK OF FLAGS 5th REVED CAMPELL & EVANS 6 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -1 PUBLICATION DIVISION 7 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -2 PUBLICATION DIVISION 8 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -3 PUBLICATION DIVISION 9 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -4 PUBLICATION DIVISION 10 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -5 PUBLICATION DIVISION 11 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -6 6 PUBLICATION DIVISION 12 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -7 PUBLICATION DIVISION 13 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -8 PUBLICATION DIVISION 14 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -9 PUBLICATION DIVISION 15 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -10 PUBLICATION DIVISION 16 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -11 PUBLICATION DIVISION 17 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -12 PUBLICATION DIVISION 18 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -13 PUBLICATION DIVISION 19 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -14 PUBLICATION DIVISION 20 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -15 PUBLICATION DIVISION 21 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL - 16 PUBLICATION DIVISION 22 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -17 PUBLICATION DIVISION 23 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -18 PUBLICATION DIVISION 24 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - -

Catalogo Libri

1 Il * terzo gemello / Ken Follett; traduzione di Annamaria Raffo. 2 Il *giardiniere tenace / John Le Carrè ; traduzione di Annamaria Biavasco e Valentina Guani. 3 Nord e sud / John Jakes ; traduzione di Tullio Dobner. 4 Seminario sulla gioventù / Aldo Busi. 5 *Vedrò Singapore? / Piero Chiara. 6 L' *uomo di Pietroburgo / Ken Follett ; traduzione di Patrizia Bonimi. 7 *Postmortem / Patricia Cornwell ; traduzione di Marco Amante. 8 Star / Danielle Steel ; traduzione di Maria Grazia Griffini. 9 *Onda D'urto / Clive Cussler ; Traduzione di Linda Pierra. 10 *Morte in seminario / P.D. James ; traduzione di Annamaria Raffo. 11 *Tre camere a Manhattan / Georges Simenon ; traduzione di Laura Frausin Guarino. 12 *Saluti notturni dal passo della Cisa / Piero Chiara. 13 *Lunga è la notte / Enzo Biagi. 14 *Op - Center Giochi di Stato / Tom Clancy e Steve Pieczenik ; traduzione di Andrea Zucchetti. 15 *Fuga dal Natale / John Grisham ; Traduzione di Tullio Dobner. 16 *Scontro fatale / Danielle Steel ; traduzione di Grazia Maria Griffini. 17 *Sorelle / Helen Van Slyke ; traduzione di Tilde Arcelli Riva. 18 *Havana / Martin Cruz Smith ; traduzione di Valentina Guani. 19 *Gotico Americano / Robert Bloch ; traduzione di Annita Biasi Conte. 20 La *semplice verità / David Baldacci Ford ; traduzione di Tullio Dobner. 21 Il *giudice / Steve Martin ; traduzione di Anna Maria Raffo. 22 *Gente senza storia / Judith Guest ; traduzione di Masolino D'Amico. 23 *Notizia di un sequestro / Gabriel Garcia Màrquez ; traduzione di Angelo Morino. 24 I *segreti della seduzione / Susan Dalmer ; traduzione Angela Boschi. 25 L'*altra faccia di mezzanotte / Sidney Sheldon ; traduzione di Bruno Oddera. 26 *Così parlò Bellavista / Luciano De Crescenzo. 27 *Parallelo Russia / Tom Clancy ; traduzione di Andrea Zucchetti. -

Edgar Parks Snow Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

July 5, 1994 revised April 19, 2010 UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI-KANSAS CITY Edgar Parks Snow (1905-1972) Papers KC:19/1/00, 4, 8, 9, 11, 12, 16, 18 1928-1972 (includes posthumous materials, 1972-1982) 718 folders, 4 scrapbooks, audio tapes, motion picture film, and photographs (173 folders) PROVENANCE The main body of the Edgar Snow Papers was donated by his widow, Lois Wheeler Snow, to the University of Missouri in 1986. Ownership of the collection passed to the University Archives in increments over several years with the last installment transferred in 1989. Additional materials from Mrs. Snow have been received as recently as 1994. BIOGRAPHY Edgar Parks Snow was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on July 19, 1905. He received his education locally and briefly attended the University of Missouri School of Journalism in Columbia. At 19, he left college and moved to New York City to embark on a career in advertising. In 1928, after making a little money in the stock market, he left to travel and write of his journeys around the world. He arrived in Shanghai July 6, 1928, and was to remain in China for the next thirteen years. His first job was with The China Weekly Review in Shanghai. Working as a foreign correspondent, he wrote numerous articles for many leading American and English newspapers and periodicals. In 1932, he married Helen (Peg) Foster, (also known as Nym Wales). The following year, the couple settled in Beijing where Snow taught at Yenching University. © University of Missouri-Kansas City Archives 5100 Rockhill Road, Kansas City, MO 64110-2499 Edgar Parks Snow Papers Inventory 04/19/2010 Page ii Edgar Snow spent part of the early 1930’s traveling over much of China on assignment for the Ministry of Railways of the National Government.