FULL CIRCLE Rajendra S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application No First Name Last Name Dob Domicile

ONLINE DOMICILE_ HSE_PE ONLINE HSE_50 GEND _ASS_5 MERIT_ APPLICATION_NO FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME DOB DISTRICT_ CASTE RCENTA _ASS_S _WEIGH ER 0_WEIG MARKS NAME GE CORE TAGE HTAGE 030412054771 AMIT TRIPATHI 31/07/1979 Jabalpur UR M 78.22 83 39.11 41.5 80.61 030412090866 NEERAJ KURARIYA 10/11/1988 Jabalpur UR M 84.22 76 42.11 38 80.11 030412050851 AMIT KURARIA 18/07/1979 Jabalpur UR M 73.78 85 36.89 42.5 79.39 030412033902 NITESH YADAV 20/04/1990 Jabalpur OBC M 75.78 79 37.89 39.5 77.39 030412003591 PIYUSH KANT VISHWAKARMA 17/06/1987 Jabalpur OBC M 85.11 67 42.56 33.5 76.06 030412017892 SHALINI SONI 21/07/1989 Jabalpur OBC F 79.78 72 39.89 36 75.89 030412067488 RUCHI KOSHTA 25/05/1988 Jabalpur OBC F 87.78 62 43.89 31 74.89 030412004013 PRABHAT PAROHA 01/08/1987 Jabalpur UR M 83.33 66 41.67 33 74.67 030412042225 SUDHANSU KUMAR 17/06/1989 Jabalpur UR M 77.11 72 38.56 36 74.56 030412077856 AARTI AGRAWAL 21/10/1989 Jabalpur UR F 90.67 58 45.34 29 74.34 030412074769 AJEET SINGH RAGHUWANSHI 01/07/1989 Jabalpur UR M 82.67 65 41.34 32.5 73.84 030412104573 POOJA AHUJA 09/05/1988 Jabalpur UR F 80.67 66 40.34 33 73.34 030412060585 UPENDRA MISHRA 10/03/1987 Jabalpur UR M 78.44 68 39.22 34 73.22 030412073393 ASHUTOSH MOGHE 28/10/1979 Jabalpur UR M 78.22 68 39.11 34 73.11 030412060496 SWATI AGRAHARI 06/08/1989 Jabalpur UR F 86 60 43 30 73 030412064398 MANISH KUMAR RAI 20/10/1986 Jabalpur OBC M 78.89 67 39.45 33.5 72.95 030412082906 ASHISH KUMAR JAIN 12/03/1986 Jabalpur UR M 86.67 59 43.34 29.5 72.84 030412084151 RATAN CHAKRAWARTI 28/04/1988 Jabalpur OBC M -

Full Circle Full Circle

FULL CIRCLE FULL CIRCLE the aboriginal healing WAYNE foundation & the K SPEAR unfinished work of hope, healing & reconciliation AHF WAYNE K SPEAR i full circle FULL CIRCLE the aboriginal healing foundation & the unfinished work of hope, healing & reconciliation WAYNE K SPEAR AHF 2014 © 2014 Aboriginal Healing Foundation Published by Aboriginal Healing Foundation Aboriginal Healing Foundation 275 Slater Street, Suite 900, Ottawa, ON, K1P 5H9 Phone: (613) 237-4441 / Fax: (613) 237-4442 Website: www.ahf.ca Art Direction and Design Alex Hass & Glen Lowry Design & Production Glen Lowry for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation Printed by Metropolitan Printing, Vancouver BC ISBN 978-1-77215-003-2 English book ISBN 978-1-77215-004-9 Electronic book Unauthorized use of the name “Aboriginal Healing Foundation” and of the Foundation’s logo is prohibited. Non-commercial reproduction of this docu- ment is, however, encouraged. This project was funded by the Aboriginal Healing Foundation but the views expressed in this report are the personal views of the author(s). contents vi acknowledgments xi a preface by Phil Fontaine 1 introduction 7 chapter one the creation of the aboriginal healing foundation 69 chapter two the healing begins 123 chapter three long-term visions & short-term politics 173 chapter four Canada closes the chapter 239 chapter five an approaching storm by Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm 281 chapter six coming full circle 287 notes 303 appendices 319 index acknowledgments “Writing a book,” said George Orwell, “is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout with some painful illness.” In the writing of this book, the usual drudgery was offset by the pleasure of interviewing a good many interesting, thoughtful and extraordinary people. -

Crime Story Collection

Crime Story Collection Level 4 Retold by John and Celia Turvey Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN 0 582 419190 This compilation first published in Longman Fiction 1998 This edition first published 1999 NEW EDITION 5 7 9 10 8 6 The story “Three is a Lucky Number” © Margery Allingham is reproduced by permission of Curtis Brown, London on behalf of P. & M.Youngman Carter Ltd. The story “Full Circle” by Sue Grafton is reprinted with the permission of Abner Stein, London. The story “How’s Your Mother?” © Simon Brett 1980 is from A Box of Tricks, published by Victor Gollancz Ltd. The story “At the Old Swimming Hole” © 1986 Sara Paretsky was first published in Mean Streets: The Second Private Eye Writers of America Anthology, edited by Robert J. Randisi, published by Mysterious Press. All rights reserved. First published in the UK by Hamish Hamilton Limited. The Patricia Highsmith story “Slowly, Slowly in the Wind” was first published in Ellery Queens Mystery Magazine 1976. Copyright © 1993 Diogenes Verlag AG, Zurich. The Patricia Highsmith story “Woodrow Wilsons Neck Tie” was first published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine 1972. Copyright © 1993 Diogenes Verlag AG, Zurich. The story “The Absence of Emily” by Jack Ritchie is reprinted with kind permission of the Larry Sterring & Jack Byrne Literary Agency, Milwaukee, United States of America. The story “The Inside Story” © 1993 Colin Dexter. This abridgement and simplification © Addison Wesley Longman Limited 1997. This edition copyright © Penguin Books Ltd 1999 Illustrations by Les Edwards Cover design by Bender Richardson White Set in 11/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/05 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. -

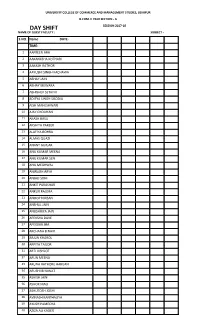

Day Shift Session 2017-18 Name of Guest Faculty : Subject - S.No

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. II YEAR SECTION - A DAY SHIFT SESSION 2017-18 NAME OF GUEST FACULTY : SUBJECT - S.NO. Name DATE- TIME- 1 AAFREEN ARA 2 AAKANKSHA KOTHARI 3 AAKASH RATHOR 4 AAYUSHI SINGH KACHAWA 5 ABHAY JAIN 6 ABHAY MEWARA 7 ABHISHEK SETHIYA 8 ADITYA SINGH SISODIA 9 AISH MAHESHWARI 10 AJAY CHOUHAN 11 AKASH BASU 12 AKSHITA PAREEK 13 ALAFIYA BOHRA 14 ALMAS QUAZI 15 ANANT GURJAR 16 ANIL KUMAR MEENA 17 ANIL KUMAR SEN 18 ANIL MEGHWAL 19 ANIRUDH ARYA 20 ANJALI SONI 21 ANKIT PARASHAR 22 ANKUR RAJORA 23 ANOOP NIRBAN 24 ANSHUL JAIN 25 ANUSHRIYA JAIN 26 APEKSHA DAVE 27 APEKSHA JHA 28 ARCHANA B NAIR 29 ARJUN KHAROL 30 ARPITA TAILOR 31 ARTI VISHLOT 32 ARUN MEENA 33 ARUNA RATHORE HARIJAN 34 ARUSHI BIYAWAT 35 ASHISH JAIN 36 ASHOK MALI 37 ASHUTOSH JOSHI 38 AVINASH KANTHALIYA 39 AYUSH PAMECHA 40 AZIZA ALI KADER 41 BATUL 42 BHARAT LOHAR 43 BHARAT MEENA 44 BHARAT PURI GOSWAMI 45 BHAVIN JAIN 46 BHAWANA SOLANKI 47 BHUMIKA JAIN 48 BHUMIKA PALIYA 49 BHUMIT SEVAK 50 BHUPENDRA JAIN 51 BINISH KHAN 52 BURHANUDDIN MOOMIN 53 CHANCHAL SOLANKI 54 CHETAN KOTIA 55 DAKSH VYAS 56 DANISH KHAN 57 DARSHIT DOSHI 58 DEEPAK NAGDA 59 DEEPAK SHRIMALI 60 DEEPIKA SAHU 61 DEEPIKA SINGH KHARWAR 62 DEEPIKA YADAV 63 DEEPTI KUMAWAT 64 DHRUVIT KUMAWAT 65 DIKSHANT VAIRAGI 66 DINESH KUMAR MEENA 67 DINESH NAGDA 68 DINESH RAJPUROHIT 69 DIPESH JAIN 70 DIVYA GUPTA 71 DIVYA JAIN 72 DIVYA MALI 73 DIVYA NAKWAL 74 DIVYA SONI 75 DURGA BHATT 76 DURGA SHANKAR MALI 77 FATEMA BOHRA 78 FIRDOSH MANSURI 79 GAJENDRA MENARIA 80 GAJENDRA PUSHKARNA Signature of Guest Faculty DEAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. -

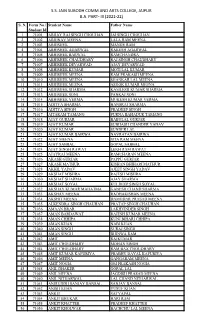

Ss Jain Subodh Comm and Arts College, Jaipur Ba Part

S.S. JAIN SUBODH COMM AND ARTS COLLEGE, JAIPUR B.A. PART- III (2021-22) S. N. Form No./ Student Name Father Name Student Id 1 71001 ABHAY RAJ SINGH CHOUHAN JAI SINGH CHOUHAN 2 71002 ABHINAV MEENA LALA RAM MEENA 3 71003 ABHISHEK MANGE RAM 4 71004 ABHISHEK AGARWAL RAKESH AGARWAL 5 71005 ABHISHEK BARWAL RAMCHANDRA 6 71006 ABHISHEK CHAUDHARY RAJ SINGH CHAUDHARY 7 71007 ABHISHEK DEVARWAD AJAY DEVARWAD 8 71008 ABHISHEK KUMAR MOTI LAL KUMAR 9 71009 ABHISHEK MEENA RAM PRAKASH MEENA 10 71010 ABHISHEK MEENA SHANKAR LAL MEENA 11 71011 ABHISHEK MEENA ASHOK KUMAR MEENA 12 71012 ABHISHEK SHARMA KAMLESH KUMAR SHARMA 13 71013 ABHISHEK SONI PANKAJ SONI 14 71014 ABHISHEK VERMA MUKESH KUMAR VERMA 15 71015 ADITYA SHARMA HANSRAJ SHARMA 16 71016 ADITYA SINGH PRADEEP SINGH 17 71017 AITARAM TAMANG PURNA BAHADUR TAMANG 18 71018 AJAY GURJAR BABULAL GURJAR 19 71019 AJAY KUMAR SUBHASH CHANDER YADAV 20 71020 AJAY KUMAR SUNDER LAL 21 71021 AJAY KUMAR BAIRWA NAVRATAN BAIRWA 22 71022 AJAY MEENA SITA RAM MEENA 23 71023 AJAY SABBAL GOPAL SABBAL 24 71024 AJAY SINGH RAWAT LEKH RAM RAWAT 25 71025 AJAYRAJ MEENA RAMCHARAN MEENA 26 71026 AKASH GURJAR PAPPU GURJAR 27 71027 AKASH MATHUR KISHAN BHIHARI MATHUR 28 71028 AKHIL YADAV AJEET SINGH YADAV 29 71029 AKSHAT MISHRA RAJESH MISHRA 30 71030 AKSHAT SHARMA AJAY SHARMA 31 71031 AKSHAT SOYAL KULDEEP SINGH SOYAL 32 71032 AKSHAY KUMAR MAHATMA GANESH CHAND SHARMA 33 71033 AKSHAY MEENA RADHAKISHAN MEENA 34 71034 AKSHIT MEENA DAMODAR PRASAD MEENA 35 71035 ALKENDRA SINGH CHAUHAN PRATAP SINGH CHAUHAN 36 71036 AMAAN BRAR LAKHVINDER SINGH -

The Rajputs: a Fighting Race

JHR1 JEvSSRAJSINGHJI SEESODIA MLJ^.A.S. GIFT OF HORACE W. CARPENTER THE RAJPUTS: A FIGHTING RACE THEIR IMPERIAL MAJESTIES KING-EMPEROR GEORGE V. AND QUEEN-EMPRESS MARY OF INDIA KHARATA KE SAMRAT SRT PANCHME JARJ AI.4ftF.SH. SARVE BHAUMA KK RAJAHO JKVOH LAKH VARESH. Photographs by IV. &* D, Downey, London, S.W. ITS A SHORT ACCOUNT OF THE , RAJPUT. ,RAC^ WARLIKE PAST, ITS EARLY CONNEC^tofe WITH., GREAT BRITAIN, AND ITS GALLANT SERVICES AT THE PRESENT MOMENT AT THE FRONT BY THAKUR SHRI JESSRAJSINGHJI SEESODIA " M.R.A.S. BEAUTIFULLY ILLUSTRATED WITH NUMEROUS COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS A FOREWORD BY GENERAL SIR O'MOORE CREAGH V.C., G.C.B., G.C.S.I. EX-COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF, INDIA LONDON EAST AND WEST, LTD. 3, VICTORIA STREET, S.W. 1915 H.H. RANA SHRI RANJITSINGHJI BAHADUR, OF BARWANI THE RAJA OF BARWANI TO HIS HIGHNESS MAHARANA SHRI RANJITSINGHJI BAHADUR MAHARAJA OF BARWANI AS A TRIBUTE OF RESPECT FOR YOUR HIGHNESS'S MANY ADMIRABLE QUALITIES THIS HUMBLE EFFORT HAS BEEN WITH KIND PERMISSION Dedicates BY YOUR HIGHNESS'S MOST OBEDIENT SERVANT AND CLANSMAN JESSRAJSINGH SEESODIA 440872 FOREWORD THAKUR SHRI JESSRAJ SINGHJI has asked me, as one who has passed most of his life in India, to write a Foreword to this little book to speed it on its way. The object the Thakur Sahib has in writing it is to benefit the fund for the widows and orphans of those Indian soldiers killed in the present war. To this fund he intends to give 50 per cent, of any profits that may accrue from its sale. -

Molecular Insight Into the Genesis of Ranked Caste Populations Of

This information has not been peer-reviewed. Responsibility for the findings rests solely with the author(s). comment Deposited research article Molecular insight into the genesis of ranked caste populations of western India based upon polymorphisms across non-recombinant and recombinant regions in genome Sonali Gaikwad1 and VK Kashyap1,2* reviews Addresses: 1National DNA Analysis Center, Central Forensic Science Laboratory, Kolkata -700014, India. 2National Institute of Biologicals, Noida-201307, India. Correspondence: VK Kasyap. E-mail: [email protected] reports Posted: 19 July 2005 Received: 18 July 2005 Genome Biology 2005, 6:P10 The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be This is the first version of this article to be made available publicly and no found online at http://genomebiology.com/2005/6/8/P10 other version is available at present. © 2005 BioMed Central Ltd deposited research refereed research .deposited research AS A SERVICE TO THE RESEARCH COMMUNITY, GENOME BIOLOGY PROVIDES A 'PREPRINT' DEPOSITORY TO WHICH ANY ORIGINAL RESEARCH CAN BE SUBMITTED AND WHICH ALL INDIVIDUALS CAN ACCESS interactions FREE OF CHARGE. ANY ARTICLE CAN BE SUBMITTED BY AUTHORS, WHO HAVE SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ARTICLE'S CONTENT. THE ONLY SCREENING IS TO ENSURE RELEVANCE OF THE PREPRINT TO GENOME BIOLOGY'S SCOPE AND TO AVOID ABUSIVE, LIBELLOUS OR INDECENT ARTICLES. ARTICLES IN THIS SECTION OF THE JOURNAL HAVE NOT BEEN PEER-REVIEWED. EACH PREPRINT HAS A PERMANENT URL, BY WHICH IT CAN BE CITED. RESEARCH SUBMITTED TO THE PREPRINT DEPOSITORY MAY BE SIMULTANEOUSLY OR SUBSEQUENTLY SUBMITTED TO information GENOME BIOLOGY OR ANY OTHER PUBLICATION FOR PEER REVIEW; THE ONLY REQUIREMENT IS AN EXPLICIT CITATION OF, AND LINK TO, THE PREPRINT IN ANY VERSION OF THE ARTICLE THAT IS EVENTUALLY PUBLISHED. -

Origin of the Rajputs : ______

ORIGIN OF THE RAJPUTS : __________________________ There is no agreement among the scholars regarding the origin of the Rajputs. It has been opined by many scholars that the Rajputs are the descendants of foreign invaders like Sakas, Kushana, white- Hunas etc. All these foreigners, who permanently settled in India, were absorbed within the Hindu society and were accorded the status of the Kshatriyas. It was only afterwards that they claimed their lineage from the ancient Kshatriya families. The other view is that the Rajputs are the descendants of the ancient Brahamana or Kshatriya families and it is only because of certain circumstances that they have been called the Rajputs. Earliest and much debated opinion concerning the origin of the Rajputs is that all Rajput families were the descendants of the Gurjaras and the Gurjaras were of foreign origin. Therefore, all Rajput families were of foreign origin and only, later on, were placed among Indian Kshatriyas and were called the Rajputs. The adherents of this view argue that we find references to the Guijaras only after the 6th century when foreigners had penetrated in India. So, they were not of Indian origin but foreigners. Cunningham described them as the descendants of the Kushanas. A.M.T. Jackson described that one race called Khajara lived in Arminia in the 4th century. When the Hunas attacked India, Khajaras also entered India and both of them settled themselves here by the beginning of the 6th century. These Khajaras were called Gurjaras by the Indians. Kalhana has narrated the events of the reign of Gurjara king, Alkhana who ruled in Punjab in the 9th century. -

Application No First Name Last Name Dob Domicil

DOMICIL ONLINE HSE_P ONLINE HSE_50 E_DISTR _ASS_5 MERIT_MA APPLICATION_NO FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME DOB CASTE GENDER ERCEN _ASS_S _WEIG ICT_NAM 0_WEIG RKS TAGE CORE HTAGE E HTAGE 030812056209 INDER SINGH KACHHWAY 09/05/1986 Ujjain SC M 89.56 67 44.78 33.5 78.28 030812023062 SHALINI TIWARI 29/04/1987 Ujjain UR F 85.78 69 42.89 34.5 77.39 030812013389 VIRENDRA MISHRA 13/07/1984 Ujjain UR M 90.22 64 45.11 32 77.11 030812093079 DHEERAJ SHARMA 08/06/1990 Ujjain UR M 84.67 66 42.34 33 75.34 030812032174 NITIN AGRAWAL 26/09/1989 Ujjain UR M 80.44 69 40.22 34.5 74.72 030812068283 RAHUL ANJANA 02/11/1989 Ujjain OBC M 81.33 67 40.67 33.5 74.17 030812001012 AJAY VISHWAKARMA 11/07/1986 Ujjain OBC M 84.89 63 42.45 31.5 73.95 030812061800 AARTI SHARMA 22/01/1991 Ujjain UR F 83.2 64 41.6 32 73.6 030812053051 HIMANSHU JAIN 31/10/1988 Ujjain UR M 80.89 65 40.45 32.5 72.95 030312081427 NAGESHWAR PANCHAL 17/12/1989 Ujjain OBC M 74.67 71 37.34 35.5 72.84 030312041110 SURESH RATHORE 01/07/1991 Ujjain SC M 88 57 44 28.5 72.5 030812014630 HEMENDRA RAWAL 31/07/1987 Ujjain UR M 74.67 70 37.34 35 72.34 030812055427 LEELADHAR PANCHAL 21/11/1991 Ujjain OBC M 85.6 59 42.8 29.5 72.3 030812086499 VIJAY DHAKITE 21/01/1986 Ujjain SC M 81.56 62 40.78 31 71.78 030812115790 GAURAV SHRIVASTAVA 08/06/1986 Ujjain UR M 75.56 68 37.78 34 71.78 030812020950 ANKIT BIHANI 25/05/1988 Ujjain UR M 77.56 66 38.78 33 71.78 030812069570 PUSHPENDRA SINGH YADAV 02/03/1987 Ujjain OBC M 85.33 58 42.67 29 71.67 030812041960 YOGENDRA CHAUHAN 09/10/1986 Ujjain UR M 75.11 68 37.56 34 71.56 030812013862 -

Amazing Grace: the Near-Death Experience As a Compensatory Gift

Amazing Grace: The Near-Death Experience as a Compensatory Gift Kenneth Ring, Ph.D. University of Connecticut ABSTRACT: This paper illustrates the apparently providential timing and the healing character of near-death experiences (NDEs) and NDE-like epi sodes, through four case histories of persons whose lives, prior to their experi ences, were marked by deep anguish and a sense of hopelessness. Spiritually, such case histories suggest the intervention of a guiding intelligence that confers a form of "amazing grace" on the recipient. Methodologically, these reports point to the importance of taking into account the person's life history as a context for understanding the full significance of NDEs and similar awakening experiences. The article ends with a retrospective account of a childhood NDE in which "the big secret" of these experiences is disclosed. "We who are about to die demand a miracle." W. H. Auden (cited in Grosso, 1985) During the past fourteen years of my research on near-death experi ences (NDEs), I have often been struck by the seemingly providential character and timing of these experiences. An individual whose life is spinning out of control and heading on a clearly self-destructive course has an accident and experiences the healing balm of absolute love and unconditional acceptance in the light, and returns to life knowing he has been set right again. A man, after several previous suicidal ges tures, takes a massive overdose of barbiturates that would ordinarily guarantee his demise, but for some unknown reason an NDE super Kenneth Ring, Ph.D., is Professor of Psychology at the University of Connecticut. -

Application No First Name Last Name Dob Domici Le Dis Trict Name Caste Gender Hse Pe Rcenta Ge Online Ass Sc Ore Hse 50 Weigh

DOMICI ONLINE_ HSE_PE ONLINE_ HSE_50_ LE_DIS ASS_50_ MERIT_ APPLICATION_NO FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME DOB CASTE GENDER RCENTA ASS_SC WEIGHTA TRICT_ WEIGHTA MARKS GE ORE GE NAME GE 030112018300 JAVED KHAN 13/08/1987 Bhopal OBC M 85.56 75 42.78 37.5 80.28 030112005050 ALKA GUPTA 31/05/1990 Bhopal UR F 79.78 70 39.89 35 74.89 030112049019 UPADHYAY SEEMA 12/04/1989 Bhopal UR F 80.67 68 40.34 34 74.34 030112075099 RITESH SHRIVASTAVA 31/10/1983 Bhopal UR M 76.44 72 38.22 36 74.22 030112080269 RACHANA SINGH 29/12/1985 Bhopal UR F 81.78 65 40.89 32.5 73.39 030112088665 NITIN YADAV 23/07/1990 Bhopal UR M 79.11 67 39.56 33.5 73.06 030112005757 SURENDRA SINGH DANGI 04/08/1979 Bhopal OBC M 60.67 85 30.34 42.5 72.84 030112016415 SHAILENDRA SINGH 10/12/1974 Bhopal OBC M 74.13 71 37.07 35.5 72.57 030112067261 PRADEEP CHOUHAN 08/05/1989 Bhopal OBC M 88 56 44 28 72 030112057789 AVINASH TIWARI 06/05/1989 Bhopal UR M 74.67 69 37.34 34.5 71.84 030112068616 HITESH MANVANI 03/06/1987 Bhopal UR M 78.22 65 39.11 32.5 71.61 030112072663 SACHIN JAIN 16/12/1986 Bhopal UR M 79.11 64 39.56 32 71.56 030112117333 AMAR SHUKLA 01/01/1989 Bhopal UR M 81.33 61 40.67 30.5 71.17 030112092140 PRITESH SINGH RAJPUT 10/09/1990 Bhopal UR M 79.33 63 39.67 31.5 71.17 030112043920 DEEPESHWAR PAWAR 19/11/1991 Bhopal UR M 80 62 40 31 71 030112056725 ANAS KHAN 03/08/1985 Bhopal UR M 75.78 66 37.89 33 70.89 030112105607 MADHU BALA SHARMA 14/02/1987 Bhopal UR F 85.56 56 42.78 28 70.78 030112058068 TANMAY JAIN 17/10/1988 Bhopal UR M 72.44 68 36.22 34 70.22 030112057398 PANKAJ PRAJAPATI 20/12/1991 -

![NCERT Notes: the Rajputs [Medieval History of India Notes for UPSC]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4956/ncert-notes-the-rajputs-medieval-history-of-india-notes-for-upsc-1674956.webp)

NCERT Notes: the Rajputs [Medieval History of India Notes for UPSC]

NCERT Notes: The Rajputs [Medieval History Of India Notes For UPSC] The North Indian Kingdoms - The Rajputs The Medieval Indian History period lies between the 8th and the 18th century A.D. Ancient Indian history came to an end with the rule of Harsha and Pulakesin II. The medieval period can be divided into two stages: • Early medieval period: 8th – 12th century A.D. • Later Medieval period: 12th-18th century. About the Rajputs • They are the descendants of Lord Rama (Surya vamsa) or Lord Krishna (Chandra vamsa) or the Hero who sprang from the sacrificial fire (Agni Kula theory). • Rajputs belonged to the early medieval period. • The Rajput Period (647A.D- 1200 A.D.) • From the death of Harsha to the 12th century, the destiny of India was mostly in the hands of various Rajput dynasties. • They belong to the ancient Kshatriya families. There were nearly 36 Rajput’ clans. The major clans were: 1. The Pratiharas of Avanti 2. The Palas of Bengal 3. The Chauhans of Delhi and Ajmer 4. The Rathors of Kanauj 5. The Guhilas or Sisodiyas of Mewar 6. The Chandellas of Bundelkhand 7. The Paramaras of Malwa 8. The Senas of Bengal 9. The Solankis of Gujarat The Pratiharas 8th-11th Century A.D • The Pratiharas were also called Gurjara. • They ruled between 8th and 11th century A.D. over northern and western India. • Pratiharas: A fortification- The Pratiharas stood as a fortification of India’s defence against the hostility of the Muslims from the days of Junaid of Sind (725.A.D.) to Mahmud of Ghazni.