Efficacy of ESHAP Regimen in Transplant Ineligible Patients with Relapsed/Refractory T-Cell Lymphoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment Regimens

HODGKIN LYMPHOMA TREATMENT REGIMENS (Part 1 of 5) Clinical Trials: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends cancer patient participation in clinical trials as the gold standard for treatment. Cancer therapy selection, dosing, administration, and the management of related adverse events can be a complex process that should be handled by an experienced health care team. Clinicians must choose and verify treatment options based on the individual patient; drug dose modifications and supportive care interventions should be administered accordingly. The cancer treatment regimens below may include both U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved and unapproved indications/regimens. These regimens are provided only to supplement the latest treatment strategies. These Guidelines are a work in progress that may be refined as often as new significant data become available. The NCCN Guidelines® are a consensus statement of its authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult any NCCN Guidelines® is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way. Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma1 Note: All recommendations are Category 2A unless otherwise indicated. Primary Treatment Stage IA, IIA Favorable (No Bulky Disease, <3 Sites of Disease, ESR <50, and No E-lesions) REGIMEN DOSING Doxorubicin + Bleomycin + Days 1 and 15: Doxorubicin 25mg/m2 IV push + bleomycin 10units/m2 IV push + Vinblastine + Dacarbazine vinblastine 6mg/m2 IV over 5–10 minutes + dacarbazine 375mg/m2 IV over (ABVD) (Category 1)2-5 60 minutes. -

R-Eshap Patient Information Leaflet Keep All Medicine

R-ESHAP PATIENT HE-I- INFORMATION 049 LEAFLET KEEP ALL MEDICINE OUT OF THE SIGHT AND REACH OF CHILDREN R-ESHAP What is R-ESHAP? R-ESHAP is the name of a combination of cancer drugs used to treat non Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). R-ESHAP is ESHAP chemotherapy with the drug rituximab. Rituximab is a type of biological therapy called a monoclonal antibody. R-ESHAP is made up of the drugs • R = Rituximab (Mabthera) • E = Etoposide - a chemotherapy drug • SH = Methylprednisolone, which is a steroid • A = Cytarabine (also known as Ara C) – a chemotherapy drug • P = Cisplatin – a chemotherapy drug How you have R-ESHAP • All the R-ESHAP drugs are clear colourless fluids. You have them into your bloodstream (intravenously). You can have them through a central line, a portacath. These are long, plastic tubes that give the drugs directly into a large vein in your chest. You have the tube put in just before your course of treatment starts and it stays in place as long as you need it. • You usually have R-ESHAP as cycles of treatment. Each cycle lasts 4 weeks. You usually have between 2 and 8 cycles. • Each cycle of treatment is given in the following way. o On the first day you have ▪ Rituximab as a slow drip (infusion) before all the other drugs – see details below ▪ Etoposide as a drip for 1 hour ▪ Methylprednisolone (steroid) as a drip for 15 to 30 minutes ▪ Cytarabine as a drip for 2 hours – this may be on the fifth day instead ▪ Cisplatin as a drip that lasts for 96 hours (4 days) o On the second, third and fourth days you ▪ Continue with your cisplatin ▪ Repeat the etoposide and methylprednisolone drips ▪ On the fifth day the cisplatin finishes and you have ▪ Another dose of methylprednisolone ▪ Another dose of cytarabine • You have no treatment for just over 3 weeks. -

Approved Amendment 2 07 May 2019 Confidentiality Notice This Document Contains Confidential Information of Amgen Inc

Product: Blinatumomab Protocol Number: 20150292 Date: 07 May 2019 Page 1 of 115 Title: A Phase 2/3 Multi-center Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Blinatumomab in Subjects With Relapsed/Refractory Aggressive B-Cell Non Hodgkin Lymphoma Amgen Protocol Number (Product Name: Blinatumomab) 20150292 EudraCT number 2016‐002044‐16 Clinical Study Sponsor: Amgen Inc. One Amgen Center Drive Thousand Oaks, California 91320 United States Phone: +1-805-447-1000 Fax: +1-805-480-4978 Key Sponsor Contact(s): Clinical Research Medical Director Email: Global Clinical Trial Manager Phone: Email: Date: 27 June 2016 Amendment 1 16 March 2017 Superseding Amendment 1: 27 April 2017 Approved Amendment 2 07 May 2019 Confidentiality Notice This document contains confidential information of Amgen Inc. This document must not be disclosed to anyone other than the site study staff and members of the institutional review board/independent ethics committee/institutional scientific review board or equivalent. The information in this document cannot be used for any purpose other than the evaluation or conduct of the clinical investigation without the prior written consent of Amgen Inc. If you have questions regarding how this document may be used or shared, call the Amgen Medical Information number: US sites, 1- 800-77-AMGEN, Canadian sites, 1-866-50-AMGEN; <<for all other countries, insert the local toll-free Medical Information number>> Amgen’s general number in the US (1-805-447-1000). NCT Number: NCT02910063 This NCT number has been applied to the document for purposes of posting on Clinical trials.gov CONFIDENTIAL Product: Blinatumomab Protocol Number: 20150292 Date: 07 May 2019 Page 2 of 115 Investigator’s Agreement I have read the attached protocol entitled “A Phase 2/3 Multi-center Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Blinatumomab in Subjects with Relapsed/Refractory Aggressive B-Cell Non Hodgkin Lymphoma,” dated 07 May 2019 and agree to abide by all provisions set forth therein. -

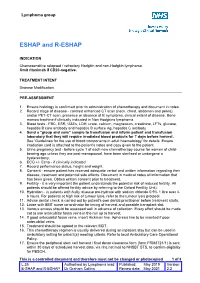

ESHAP and R-ESHAP

Lymphoma group ESHAP and R-ESHAP INDICATION Chemosensitive relapsed / refractory Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Omit rituximab if CD20-negative. TREATMENT INTENT Disease Modification. PRE-ASSESSMENT 1. Ensure histology is confirmed prior to administration of chemotherapy and document in notes. 2. Record stage of disease - contrast enhanced CT scan (neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis), and/or PET-CT scan, presence or absence of B symptoms, clinical extent of disease. Bone marrow trephine if clinically indicated in Non Hodgkins lymphoma. 3. Blood tests - FBC, ESR, U&Es, LDH, urate, calcium, magnesium, creatinine, LFTs, glucose, hepatitis B core antibody and hepatitis B surface Ag, hepatitis C antibody 4. Send a "group and save" sample to transfusion and inform patient and transfusion laboratory that they will require irradiated blood products for 7 days before harvest. See ‘Guidelines for the use of blood components in adult haematology' for details. Ensure irradiation card is attached to the patient's notes and copy given to the patient. 5. Urine pregnancy test • before cycle 1 of each new chemotherapy course for women of child- bearing age unless they are post-menopausal, have been sterilised or undergone a hysterectomy. 6. ECG +/- Echo - if clinically indicated. 7. Record performance status, height and weight. 8. Consent - ensure patient has received adequate verbal and written information regarding their disease, treatment and potential side effects. Document in medical notes all information that has been given. Obtain written consent prior to treatment. 9. Fertility - it is very important the patient understands the potential risk of reduced fertility. All patients should be offered fertility advice by referring to the Oxford Fertility Unit). -

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (Part 1 of 5)

NON-HODGKIN LYMPHOMA TREATMENT REGIMENS: Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (Part 1 of 5) Clinical Trials: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends cancer patient participation in clinical trials as the gold standard for treatment. Cancer therapy selection, dosing, administration, and the management of related adverse events can be a complex process that should be handled by an experienced health care team. Clinicians must choose and verify treatment options based on the individual patient; drug dose modifications and supportive care interventions should be administered accordingly. The cancer treatment regimens below may include both U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved and unapproved indications/regimens. These regimens are provided only to supplement the latest treatment strategies. These Guidelines are a work in progress that may be refined as often as new significant data become available. The NCCN Guidelines® are a consensus statement of its authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult any NCCN Guidelines® is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way. Systemic Therapy for Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma1 Note: All recommendations are Category 2A unless otherwise indicated. First-line Therapy REGIMEN DOSING R-CHOP (Category 1)2–7 Days 1, 22, and 43: Rituximab 375mg/m2 IV 7 days prior to beginning CHOP regimen Day 1: Cyclophosphamide 750mg/m2 IV + doxorubicin 50mg/m2 IV bolus + vincristine 1.4mg/m2 IV bolus (max dose 2mg) Days 3, 24, and 45: Prednisone 100mg orally 5 days. -

Therapy-Related Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Patients with Lymphoma: a Report of Four Cases and Review of the Literature

ONCOLOGY LETTERS 10: 3261-3265, 2015 Therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia in patients with lymphoma: A report of four cases and review of the literature DAN YANG1*, XIAORUI FU1*, XUDONG ZHANG1, WENCAI LI2 and MINGZHI ZHANG1 1Lymphoma Diagnosis and Treatment Center, Department of Oncology; 2Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China Received November 20, 2014; Accepted July 30, 2015 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2015.3703 Abstract. Due to advances in the treatment of lymphoma, of immunotherapy for the treatment of cancer, particularly the remission and overall survival rates for this disease for cases of relapsed and refractory lymphoma or leukemia. have improved in recent years. However, the incidence of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid Introduction leukemia (t-MDS/AML) has increased. In order to further the understanding of the mechanisms of t-MDS/AML and reduce It is well known that chemotherapeutic agents and ionizing its incidence, the present study reports 4 cases of t-AML radiation are carcinogens, and may cause DNA damage following treatment for lymphoma. The 4 patients presented through double-strand breaks and loss of elements of the DNA aggressive forms of lymphoma in stage III/IV, and 3 were mismatch repair system, resulting in genomic instability (1,2). diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. All patients had The development of hematopoietic neoplasms in patients who previously undergone chemotherapy containing alkylating had received chemotherapy/radiation was first identified by agents and/or topoisomerase II inhibitors. The latency period Crosby et al in 1969 (3). In the 2008 World Health Organiza- between the time of primary diagnosis and occurrence of tion (WHO) Classification of Hematopoietic Neoplasms (4), t-AML ranged from 15 to 42 months. -

Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy of Human Cancers

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author J Cancer Manuscript Author Sci Ther. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2020 March 06. Published in final edited form as: J Cancer Sci Ther. 2019 ; 11(4): . Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy of Human Cancers Andrea Brown, Sanjay Kumar, Paul B Tchounwou* Cellomics and Toxicogenomics Research Laboratory, NIH/NIMHD-RCMI Center for Environmental Health, College of Science, Engineering and Technology, Jackson State University, 1400 Lynch Street, Box18750, Jackson, Mississippi, MS 39217, USA Abstract Cisplatin (cis-diammine-dichloro-platinum II) was initially discovered to prevent the growth of Escherichia coli and was further recognized for its anti-neoplastic and cytotoxic effects on cancer cells. Administered intravenously to humans, cisplatin is used as first-line chemotherapy treatment for patients diagnosed with various types of malignancies, such as leukemia, lymphomas, breast, testicular, ovarian, head and neck, and cervical cancers, and sarcomas. Once cisplatin enters the cell it exerts its cytotoxic effect by losing one chloride ligand, binding to DNA to form intra-strand DNA adducts, and inhibiting DNA synthesis and cell growth. The DNA lesions formed from cisplatin-induced DNA damage activate DNA repair response via NER (nuclear excision repair system) by halting cisplatin-induced cell death by activation of ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) pathway. Although treatment has been shown to be effective, many patients experience relapse due to drug resistance. As a result, other platinum compounds such as oxaliplatin and carboplatin have since been used and have shown some levels of effectiveness. In this review, the clinical applications of cisplatin are discussed with a special emphasis on its use in cancer chemotherapy. -

Study Design

Phase I/II Study of Bendamustine in Combination with Ofatumumab, Carboplatin and Etoposide for Refractory or Relapsed Aggressive B-cell Lymphomas. AUTHORS Principal Investigator Joanne Filicko-O’Hara, MD Co-Investigators S. Onder Alpdogan, MD Matthew Carabasi, MD Jerald Gong, MD Margaret Kasner, MD Neal Flomenberg, MD Ubaldo Martinez, MD John L.Wagner, MD Dolores Grosso, DNP, CRNP Avnish Bhatia, MD Andrew Chapman, DO Michael Ramirez, MD Lewis Rose, MD Atrayee Basu-Mallick, MD Allison Zibelli, MD Christina Brus, MD Sameh Gaballa, MD Pierluigi Porcu, MD Neil Palmisiano, MD Lindsay Wilde, MD Biostatistician Inna Chervoneva, PhD Division of Hematologic Malignancies and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Department of Medical Oncology Kimmel Cancer Center Thomas Jefferson University 834 Chestnut Street, Suite # 320, Philadelphia, Pa 19107 Phone (215) 503-5894 Original Date: 7.19.11 (Version 1.0) Updated Protocol 1.12.12 (Version 1.2) Versions 7.31.12 (Version 1.3) 10.4.11 (Version 1.1) 1 Protocol Version 6.3 1.7.13 (Version 2.0) 4.2.13 (Version 2.1) 6.5.13 (Version 2.2) 3.12.14 (Version 3.0) 12.31.14 (Version 3.1) 2.4.15 (Version 3.2) 8.12.15 (Version 4.0) 9.10.15 (Version 5.0) 11.13.15 (Version 5.1) 02.11.16 (Version 5.2) 05.27.16 (Version 6.0) 03.10.17 (Version 6.1) 11.16.17 (Version 6.2) 09.17.18 (Version 6.3) 2 Protocol Version 6.3 INDEX STUDY SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 1.1 BACKGROUND …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 1.2 INVESTIGATIONAL AGENT-OFATUMUMAB………………………………………………………………………………….13 -

Zevalin Clinical Trial Protocol

PHASE II TRIAL OF YTTRIUM-90-IBRITUMOMAB TIUXETAN (ZEVALIN®) RADIOIMMUNOTHERAPY AFTER CYTOREDUCTION WITH ESHAP CHEMOTHERAPY IN PATIENTS WITH RELAPSED FOLLICULAR NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA (PROTOCOL # 106-P158; 009-004-ZEV) The University of Arizona Cancer Center 1515 N. Campbell Ave. Tucson, AZ 85724 PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Daniel O. Persky, MD PROTOCOL DATE: Amendment #9: 28 August 2017 • Amendment #8: 19 April 2017 • Amendment #7: 7 January 2013 • Amendment #6: 28 June 2010 • Amendment #5: 21 May 2010 • Amendment #4: 1 April 2010 • Amendment #3: 15 January 2009 • Amendment #2: 27 April 2007 • Amendment #1: 1 March 2006 • Initial Protocol: 15 April 2005 Amendment #9: 08/28/2017 [1] Protocol Signature Page Protocol Title: PHASE II TRIAL OF YTTRIUM-90-IBRITUMOMAB TIUXETAN (ZEVALIN®) RADIOIMMUNOTHERAPY AFTER CYTOREDUCTION WITH ESHAP CHEMOTHERAPY IN PATIENTS WITH RELAPSED FOLLICULAR NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA Protocol Version/Date: 28 August 2017 I agree to conduct the study as outlined in the protocol and to comply with all the terms and conditions set out therein. I confirm that I will conduct the study in accordance with FDA and ICH GCP guidelines and all other applicable regulatory requirements. I also will ensure that sub-investigator(s) and other relevant members of my staff have access to copies of this protocol. ______________________________________ ______________________ Signature of Principal Investigator Date of Signature Daniel O. Persky, MD Printed Name of Principal Investigator The University of Arizona Cancer Center Institution 1515 N. Campbell Ave. Address Tucson, AZ 85724 City, State, Zip Amendment #9: 08/28/2017 [2] TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page…………………………………………………………………………... 01 Protocol Signature Page……………………………………………………………. -

The Role of Glucocorticoids in the Treatment of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Open Access Annals of Hematology & Oncology Review Article The Role of Glucocorticoids in the Treatment of Non- Hodgkin Lymphoma Lamar ZS1,2* 1Department of Internal Medicine, Section on Abstract Hematology and Oncology, Wake Forest School of First line chemotherapy for aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) Medicine, USA typically involves high doses of glucocorticoids (GCs) over several days. The 2Comprehensive Cancer Center, Wake Forest Baptist most commonly used combination chemotherapy regimen for NHL includes Medical Center, Winston Salem, USA cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) or given *Corresponding author: Zanetta S. Lamar, with rituximab (R-CHOP). The dose of prednisone used in the R-CHOP Department of Internal Medicine, Section on Hematology regimen varies in historical studies and in current clinical trials. There is a and Oncology, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medical paucity of prospective data outlining the management of hyperglycemia during Center Blvd, Winston Salem, NC 27157, USA chemotherapy in diabetics or the risk of hyperglycemia or steroid-induced hyperglycemia during or following chemotherapy. Often, the adverse short and Received: June 18, 2016; Accepted: August 22, 2016; long-term effects of high doses of GCs are not reported in clinical trials. We Published: August 24, 2016 will discuss the history of GC incorporation into combination chemotherapy for lymphoma, the potential implications of liberal GC use in this population, and the opportunities for further research. Keywords: Glucocorticoid; Steroid; Non-Hodgkin lymphoma; Diabetes; Cancer; Hyperglycemia Introduction apoptosis is dependent on adequate levels of the GCR, the mechanism of GC-induced apoptosis is complex and involves multiple signaling Glucocorticoids (GCs) are a class of steroid hormones produced pathways [10,11]. -

Response and Toxicity to Cytarabine Therapy in Leukemia and Lymphoma: from Dose Puzzle to Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers

cancers Review Response and Toxicity to Cytarabine Therapy in Leukemia and Lymphoma: From Dose Puzzle to Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers Raffaele Di Francia 1 , Stefania Crisci 2 , Angela De Monaco 3, Concetta Cafiero 4,*, Agnese Re 5, Giancarla Iaccarino 2, Rosaria De Filippi 2,6, Ferdinando Frigeri 7, Gaetano Corazzelli 2, Alessandra Micera 8,* and Antonio Pinto 2 1 Italian Association of Pharmacogenomics and Molecular Diagnostics, 60126 Ancona, Italy; [email protected] 2 Hematology-Oncology and Stem Cell transplantation Unit, National Cancer Institute, Fondazione “G. Pascale” IRCCS, 80131 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (G.I.); rdefi[email protected] (R.D.F.); [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (A.P.) 3 Clinical Patology, ASL Napoli 2 Nord, “S.M. delle Grazie Hospital”, 80078 Pozzuoli, Italy; [email protected] 4 Medical Oncology, S.G. Moscati, Statte, 74010 Taranto, Italy 5 Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, 00168 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 6 Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Federico II University, 80131 Naples, Italy 7 UOC Onco-Hematology, AORN SS Anna e Sebastiano, 81100 Caserta, Italy; [email protected] 8 Research and Development Laboratory for Biochemical, Molecular and Cellular Applications in Ophthalmological Sciences, IRCCS—Fondazione Bietti, 00184 Rome, Italy * Correspondence: concetta.cafi[email protected] or concettacafi[email protected] (C.C.); Citation: Di Francia, R.; Crisci, S.; De [email protected] (A.M.); Tel.:+39-34-0101-2002 (C.C.); +39-06-4554-1191 (A.M.) Monaco, A.; Cafiero, C.; Re, A.; Iaccarino, G.; De Filippi, R.; Frigeri, F.; Simple Summary: In this review, the authors propose a crosswise examination of cytarabine-related Corazzelli, G.; Micera, A.; et al. -

Rapid Infusion of Rituximab with Or Without Steroid-Containing Chemotherapy: 1-Yr Experience in a Single Institution

Eur J Haematol 2006: 77: 338–340 Ó 2006 The Authors doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2006.00713.x Journal compilation Ó 2006 Blackwell Munksgaard All rights reserved EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF HAEMATOLOGY Rapid infusion of rituximab with or without steroid-containing chemotherapy: 1-yr experience in a single institution Salar A, Casao D, Cervera M, Pedro C, Calafell M, Abella E, Alvarez- Antonio Salar, Dolors Casao, Marta Larra´n A, Besses C. Rapid infusion of rituximab with or without Cervera, Carmen Pedro, Montserrat steroid-containing chemotherapy: 1-yr experience in a single institution. Calafell, Eugenia Abella, Alberto Alvarez-Larrn, Carlos Besses Department of Clinical Hematology, Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Spain Abstract: We assessed the feasibility of a rapid infusion of rituximab with or without steroid-containing chemotherapy. Inclusion criteria: Key words: rituximab; lymphoma; drug administration; previous infusion of rituximab without grade 3 or 4 toxicity, lymphoid monoclonal antibody cells <5 · 109/L and rituximab dose of 375 mg/m2. Seventy patients Correspondence: Antonio Salar, MD, PhD, Department were treated with a total of 319 rapid rituximab infusions [126 (40%) of Clinical Hematology, Hospital del Mar, Passeig with and 193 (60%) without steroids]. Overall, rapid infusion of ritux- Maritim 25-29, 08003 Barcelona, Spain imab was well tolerated – there were no grade 3 or 4 adverse events. Tel: +34-9324-83341 Only, three patients developed symptoms, all grade 1. In conclusion, Fax: +34-9324-83254 rituximab administration in a 90-min infusion schedule is well tolerated e-mail: [email protected] and safe, both in patients who are administered steroids and in patients who are not.