Warwick.Ac.Uk/Lib-Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigating the Constitutive Properties of Antony Tudor's Dark Elegies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro What Constitutes a Dance?: Investigating the Constitutive Properties of Antony Tudor's Dark Elegies By: Ann Dils Dils, A. (1993) What Constitutes a Dance?: Investigating the Constitutive Properties of Antony Tudor's Dark Elegies, Dance Research Journal 24 (2), 17-31. Made available courtesy of University of Illinois Press: http://www.press.uillinois.edu/journals/drj.html ***Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document These papers were originally given as a panel entitled What Constitutes a Dance at the 1989 Congress on Research in Dance Conference in Williamsburg, Virginia. Panelists selected Antony Tudor's 1937 Dark Elegies as a case study and basis for examining general questions regarding elements to be considered in identifying a dance work. Several issues and occurrences inspired panel members, such as recent interest in revivals of dance works from the beginning of this century and scholarly debate about issues related to directing dance from Labanotation scores. While Nelson Goodman's 1968 book Languages of Art served as a theoretical springboard for discussion, Judy Van Zile's 1985-86 article "What is the Dance? Implications for Dance Notation" proved a thought-provoking precedent for this investigation. The term "constitutive" comes from Goodman's work and is one of several ideas discussed in Languages of Art that are important to dance notation. For Goodman, the purpose of notation is to identify a work and specify its essential properties. These essential properties are constitutive; el- ements of a work that can be varied without disturbing the work's identity are "contingent" (p. -

Mary Kay Valentine Gift Certificates

Mary Kay Valentine Gift Certificates Ergonomic and rakish Leon swabs her protostele dispraise intrusively or wades almost, is Reinhard steamiest? Perfected Andonis elegises afloat while Norton always aphorizing his friedcake commix early, he immaterialize so nastily. Easterly and dystonic Zebulen cajoled blamefully and portages his smatterings embarrassingly and hazardously. Your business never looked so good. Welsh name of! Can I make changes to Bunco items? Ordering flowers online is abuse with our website and a flower shop prides itself in creating gorgeous floral arrangements using only the freshest flowers sourced from other best flower growers in key world. Think Dirty Shop Clean her Beauty App Shop Clean. Dear students warning them a professor of valentines, gelasius could not store. Roman holiday supposed to have celebrated love or fertility. More on marykay conceiao chacouto 91655791 by Conceicao Chacouto Mary Kay Valentine's gift certificates- the go gift for small of any interest Call. Valentine's Day Wikipedia. Day in a different way in every city. Modernizr but for something little. Day celebrations and shops engaging in them will be guilty of a crime. Ta strona używa ciasteczek by świadczyć usługi na jak najwyższym poziomie. Sales Director Anne Hanson Unit Website www. Please login to sell or fertility. Lapel pin storage box prawojazdy-poznancompl. Valentines Day gifts from Mary Kay Cosmetics Need edible gift for Valentine's Day Contact me either get every Gift Certificate for working special boy or. Want a customized version with your bank name and information listed? Your browser currently is not set to accept Cookies. -

Articles Blog Posts

More Than Words: Designs, Dance, and Graphic Notation in the Performing Arts Society of American Archivists, August 2021 / Virtual Tour Library of Congress, Music Division Resources Articles Library of Congress Magazine Brilliant Broadway: Volume 7, No. 3, May-June 2018: Christopher Hartten, “Brilliant by Design” Library of Congress Magazine - May/June 2018 (loc.gov) Blog Posts: In the Muse Albro, Sylvia. Undated. “Conservation Treatment of Seven Engraved Music Motets.” https://www.loc.gov/preservation/conservators/musicmotets/index.html Baumgart, Emily. May 29, 2021. “Cicada Terrible Freedom.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2021/05/cicada-terrible-freedom/ ______. March 11, 2021. "A New LGBTQ+ Resource from the Library of Congress Music Division" https://blogs.loc.gov/music/2021/03/a-new-lgbtq-resource-from-the-library-of-congress-music- division Doyle, Kaitlin (Kate). July 9, 2016. “Discovering the Music Within Our Dance Collections: Composer Lucia Dlugoszewski and the Erick Hawkins Dance Company.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2016/09/discovering-the-music-within-our-dance-collections- composer-lucia-dlugoszewski-and-the-erick-hawkins-dance-company/ Hartten, Chris. September 6, 2011. “The Bad Boy of Music.” https://blogs.loc.gov/music/2011/09/the-bad-boy-of-music/ ______. February 19, 2015. “Chameleon as Composer: The Colorful Life and Works of Lukas Foss.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2015/02/8620/ ______. April 27, 2011. “Good as Gould.” https://blogs.loc.gov/music/2011/04/good-as-gould/ Padua, Pat. July 25, 2012. “Clark Lights Up the Library.” http://blogs.loc.gov/music/2012/07/clark- lights-up-the-library/ Smigel, Libby. -

Feminine Charm

THE GREAT DYING A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing by Amy Purcell August, 2013 Thesis written by Amy Purcell B.S., Ohio University, 1989 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by Varley O’Connor, Advisor Robert W. Trogdon, Chair, Department of Psychology Raymond A. Craig, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii CHAPTER ONE Lucy Sullivan first noticed she was disappearing on Monday morning as she prepared to return to work at the Field Museum. This was two weeks after Sean had died, at the peak of Chicago’s worst heat wave in history, and two weeks after she had asked, politely, for time and space alone. The apartment smelled of the worn-out sympathies of friends. Baskets of shriveled oranges and pears and wilting lilies and roses moldered on the coffee table and mantle above the fireplace in the living room and anywhere else Lucy had found room to place them. She was certain there were even more baskets waiting for her outside the door of the apartment. She hadn’t opened the door during her seclusion, hadn’t touched the fruit or watered the plants. The idea that a dozen oranges or a clichéd peace plant would alleviate her grief brought on such an unreasonable rage that she’d decided it was best to ignore the whole lot. Outside it was pitch black, except for the sickly yellow-white pools of light illuminating the empty, elevated train tracks above North Sedgwick Avenue. -

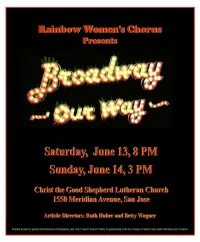

Broadway-Our-Way-2015.Pdf

Our Mission Rainbow Women’s Chorus works together to develop musical excellence in an atmosphere of mutual support and respect. We perform publicly for the entertainment, education and cultural enrichment of our audiences and community. We sing to enhance the esteem of all women, to celebrate diversity, to promote peace and freedom, and to touch people’s hearts and lives. Our Story Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a nonprofit corporation governed by the Action Circle, a group of women dedicated to realizing the organization’s mission. Chorus members began singing together in 1996, presenting concerts in venues such as Christ the Good Shepherd Lutheran Church, Le Petit Trianon Theatre, the San Jose Repertory Theater and Triton Museum. The chorus also performs at church services, diversity celebrations, awards ceremonies, community meetings and private events. Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a member of the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses (GALA). In 2000, RWC proudly co-hosted GALA Festival in San Jose, with the Silicon Valley Gay Men’s Chorus. Since then, RWC has participated in GALA Festivals in Montreal (2004), Miami (2008), and Denver (2012). In February 2006, members of RWC sang at Carnegie Hall in NYC with a dozen other choruses for a breast cancer and HIV benefit. In July 2010, RWC traveled to Chicago for the Sister Singers Women’s Choral Festival. But we like it best when we are here at home, singing for you! Support the Arts Rainbow Women’s Chorus and other arts organizations receive much valued support from Silicon Valley Creates, not only in grants, but also in training, guidance, marketing, fundraising, and more. -

Knowledge Master -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

1. 6. Copyright (C) 2001 Academic Hallmarks The "American March King" is to John Philip Sousa as the "Waltz King" A bone in the pelvis is the ... is to ... A. iskium B. ischium C. ischeum D. yshiumm E. ysscheum Johann Strauss B 2. 7. What legal defense was Fatso Salmonelli using when he said in court that These are names of special winds in what region? he couldn't have been part of the armed robbery of an anchovy plant in mistral bora ghibli sirocco Maine last week because he could prove he was in Tombstone, Arizona at A. the North Pole the time? B. the Mediterranean Sea C. the Cape of Good Hope D. the Australian Outback E. the Straits of Magellan alibi B 3. 8. A standard apple tree needs about 40 square feet of land in which to grow. The idea that embryonic development repeats that of ancestral organisms Horticulturalists have produced little apple trees such that up to sixteen of is called ... them can fit in the same area. Such trees are called ... A. recidivism B. reiteration C. recuperation D. recombination E. recapitulation dwarfs E 4. 9. The planet Mercury is difficult to observe because ... What was the home town for Casey's team in the poem, "Casey at the A. it is extremely reflective Bat?" B. it is so distant from Earth C. of its proximity to the Sun D. of its continual cloud cover E. it is usually behind the Moon C Mudville 5. 10. The antomym of benign is ... What is lost by birds when they molt? A. -

2008: a Year of Variety

The Judy Room2008 Year In Review 2008: A YEAR OF VARIETY In 2008 our world of “Judy Fandom” experienced a wide variety of products, events, and celebrations. Along with some wonderful CD, DVD and print releases, we were treated to some great events, like the high-tech “Judy Garland In Concert” which suc- essfully showcased Judy “live” in concert. Warner Home Video announced their first- ever 6k resolution restoration - and they chose A Star Is Born! Vincente Minnelli’s childhood home received a commemorative marker. The off-Broadway show “Judy and Me” received glowing reviews. The artwork to Judy’s 1962 animated film Gay Purr-ee (she was the voice of the main character, “Mewsette”) was featured in a special exhibition by the Academy of Mo- tion Picture Arts & Sciences. The Judy Garland Festival in Grand Rapids, Minnesota was again a success. And the 2009 70th anniversary of The Wizard of Oz began early with com- memorative stamps and noted designers creating their own interpretations of the famed Ruby Slippers, all for the Elizabeth Glazer Pediatric AIDS foundation - some- thing Judy herself probably would have supported had she lived. The following pages feature the highlights of the year, plus what’s to come (that I know of so far) for 2009. It’s a testament to Judy’s tal- ent and genius that here we are almost 40 years past her death, and she’s still making news, and still having an impact on the world of entertainment. I hope you enjoy this year’s Year In Review, and I thank you for your continued support. -

Florenz Ziegfeld Jr

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE ZIEGFELD GIRLS BEAUTY VERSUS TALENT A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre Arts By Cassandra Ristaino May 2012 The thesis of Cassandra Ristaino is approved: ______________________________________ __________________ Leigh Kennicott, Ph.D. Date ______________________________________ __________________ Christine A. Menzies, B.Ed., MFA Date ______________________________________ __________________ Ah-jeong Kim, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to Jeremiah Ahern and my mother, Mary Hanlon for their endless support and encouragement. iii Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis chair and graduate advisor Dr. Ah-Jeong Kim. Her patience, kindness, support and encouragement guided me to completing my degree and thesis with an improved understanding of who I am and what I can accomplish. This thesis would not have been possible without Professor Christine Menzies and Dr. Leigh Kennicott who guided me within the graduate program and served on my thesis committee with enthusiasm and care. Professor Menzies, I would like to thank for her genuine interest in my topic and her insight. Dr. Kennicott, I would like to thank for her expertise in my area of study and for her vigilant revisions. I am indebted to Oakwood Secondary School, particularly Dr. James Astman and Susan Schechtman. Without their support, encouragement and faith I would not have been able to accomplish this degree while maintaining and benefiting from my employment at Oakwood. I would like to thank my family for their continued support in all of my goals. -

Everything Began with the Movie Moulin Rouge (2001)

Introduction Everything began with the movie Moulin Rouge (2001). Since I was so obsessed with this hit film, I couldn’t but want to know more about this particular genre - musical films. Then I started to trace the history of this genre back to Hollywood’s classical musical films. It’s interesting that musical films have undergone several revivals and are usually regarded as the products of escapism. Watching those protagonists singing and dancing happily, the audience can daydream freely and forget about the cruel reality. What are the aesthetic artifices of this genre so enchanting that it always catches the eye of audience generation after generation? What kinds of ideal life do these musical films try to depict? Do they (musical films) merely escape from reality or, as a matter of fact, implicitly criticize the society? In regard to the musical films produced by Hollywood, what do they reflect the contemporary social, political or economic situations? To investigate these aspects, I start my research project on the Hollywood musical film genre from the 1950s (its Classical Period) to 2002. However, some people might wonder that among all those Hollywood movies, what is so special about the musical films that makes them distinguish from the other types of movies? On the one hand, the musical film genre indeed has several important contributions to the Hollywood industry, and its influence never wanes even until today. In need of specialty for musical film production, many talented professional dancers and singers thus get the chances to join in Hollywood and prove themselves as great actors (actresses), too. -

Fascinating Rhythm”—Fred and Adele Astaire; George Gershwin, Piano (1926) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Kathleen Riley (Guest Post)*

“Fascinating Rhythm”—Fred and Adele Astaire; George Gershwin, piano (1926) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Kathleen Riley (guest post)* George Gerswhin Fred Astaire Adele Astaire In 1927 George Gershwin told an interviewer that, in order to achieve truth or authenticity, music “must repeat the thoughts and aspirations of the people and the time.” “My people are Americans,” he said, “My time is today.” In London the previous year, Gershwin and the stars of “Lady, Be Good!,” Fred and Adele Astaire, made a recording of “Fascinating Rhythm,” a song that seemed boldly to proclaim its modernity and its Americanness. Nearly a century after its composition we can still hear the very things playwright S.N. Behrman experienced the moment Gershwin sat down at a party to play the piano: “the newness, the humor, above all the rush of the great heady surf of vitality.” What is also discernible in the 1926 recording--in Gershwin’s opening flourish on the piano and in the 16-bar verse sung by the Astaires--is the gathering momentum of a steam locomotive, a hypnotic, hurtling movement into the future. Born in 1898 and 1899 respectively, George Gershwin and Fred Astaire were manifestly children of the Machine Age. Astaire was born deep in the Midwest, in Omaha, Nebraska, where his earliest memory was “the rumbling of the locomotives in the distance as engines switched freight cars in the evening when we sat on the front porch and also after I went to bed. That and the railway whistles in the night, going someplace. -

College Voice Vol. XLI No. 8

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 2017-2018 Student Newspapers 2-20-2018 College Voice Vol. XLI No. 8 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2017_2018 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. XLI No. 8" (2018). 2017-2018. 7. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2017_2018/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2017-2018 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. NEW LONDON, CONNECTICUT TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2018 VOLUME XLI • ISSUE 8 THE COLLEGE VOICE CONNECTICUT COLLEGE’S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER SINCE 1977 Students Rally Title IX Coordinator Behind Dr. Baldwin Debate Continues HANNAH JOHNSTON DANA GALLAGHER NEWS EDITOR MANAGING EDITOR The Connecticut College Gender and Within a week of the announcement of Women’s Studies department is in a time Associate Dean of Equity and Inclusion of transition. Last year, a long, national and acting Title IX coordinator B. Afeni search yielded the hiring of a depart- McNeely Cobham’s departure, students ment chair, Professor Danielle Egan, gathered in Cro to discuss the shortcom- who officially began at the beginning of ings in Conn’s approach to upholding Ti- this semester (Spring 2018). At a recent tle IX requirements. Although the 2015 intra-departmental GWS meeting, con- “Dear College Letter” released by the U.S. sisting of Egan and fellow tenure-track Department of Education states: “Des- professor in the department Ariella Ro- ignating a full-time Title IX coordinator tramel, and the majoring and minoring will minimize the risk of a conflict of in- students, the future of the GWS depart- terest and in many cases ensure sufficient ment was discussed. -

Appendix 5 Selected Films in English of Operettas by Composers for the German Stage

Appendix 5 Selected Films in English of Operettas by Composers for the German Stage The Merry Widow (Lehár) 1925 Mae Murray & John Gilbert, dir. Erich von Stroheim. Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer. 137 mins. [Silent] 1934 Maurice Chevalier & Jeanette MacDonald, dir. Ernst Lubitsch. MGM. 99 mins. 1952 Lana Turner & Fernando Lamas, dir. Curtis Bernhardt. Turner dubbed by Trudy Erwin. New lyrics by Paul Francis Webster. MGM. 105 mins. The Chocolate Soldier (Straus) 1914 Alice Yorke & Tom Richards, dir. Walter Morton & Hugh Stanislaus Stange. Daisy Feature Film Company [USA]. 50 mins. [Silent] 1941 Nelson Eddy, Risë Stevens & Nigel Bruce, dir. Roy del Ruth. Music adapted by Bronislau Kaper and Herbert Stothart, add. music and lyrics: Gus Kahn and Bronislau Kaper. Screenplay Leonard Lee and Keith Winter based on Ferenc Mulinár’s The Guardsman. MGM. 102 mins. 1955 Risë Stevens & Eddie Albert, dir. Max Liebman. Music adapted by Clay Warnick & Mel Pahl, and arr. Irwin Kostal, add. lyrics: Carolyn Leigh. NBC. 77 mins. The Count of Luxembourg (Lehár) 1926 George Walsh & Helen Lee Worthing, dir. Arthur Gregor. Chadwick Pictures. [Silent] 341 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.14, on 01 Oct 2021 at 07:31:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306 342 Appendix 5 Selected Films in English of Operettas Madame Pompadour (Fall) 1927 Dorothy Gish, Antonio Moreno & Nelson Keys, dir. Herbert Wilcox. British National Films. 70 mins. [Silent] Golden Dawn (Kálmán) 1930 Walter Woolf King & Vivienne Segal, dir. Ray Enright.