Agenda for September 26, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speed Kills / Hannibal Production in Association with Saban Films, the Pimienta Film Company and Blue Rider Pictures

HANNIBAL CLASSICS PRESENTS A SPEED KILLS / HANNIBAL PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH SABAN FILMS, THE PIMIENTA FILM COMPANY AND BLUE RIDER PICTURES JOHN TRAVOLTA SPEED KILLS KATHERYN WINNICK JENNIFER ESPOSITO MICHAEL WESTON JORDI MOLLA AMAURY NOLASCO MATTHEW MODINE With James Remar And Kellan Lutz Directed by Jodi Scurfield Story by Paul Castro and David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Screenplay by David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Based upon the book “Speed Kills” by Arthur J. Harris Produced by RICHARD RIONDA DEL CASTRO, pga LUILLO RUIZ OSCAR GENERALE Executive Producers PATRICIA EBERLE RENE BESSON CAM CANNON MOSHE DIAMANT LUIS A. REIFKOHL WALTER JOSTEN ALASTAIR BURLINGHAM CHARLIE DOMBECK WAYNE MARC GODFREY ROBERT JONES ANSON DOWNES LINDA FAVILA LINDSEY ROTH FAROUK HADEF JOE LEMMON MARTIN J. BARAB WILLIAM V. BROMILEY JR NESS SABAN SHANAN BECKER JAMAL SANNAN VLADIMIRE FERNANDES CLAITON FERNANDES EUZEBIO MUNHOZ JR. BALAN MELARKODE RANDALL EMMETT GEORGE FURLA GRACE COLLINS GUY GRIFFITHE ROBERT A. FERRETTI SILVIO SARDI “SPEED KILLS” SYNOPSIS When he is forced to suddenly retire from the construction business in the early 1960s, Ben Aronoff immediately leaves the harsh winters of New Jersey behind and settles his family in sunny Miami Beach, Florida. Once there, he falls in love with the intense sport of off-shore powerboat racing. He not only races boats and wins multiple championship, he builds the boats and sells them to high-powered clientele. But his long-established mob ties catch up with him when Meyer Lansky forces him to build boats for his drug-running operations. Ben lives a double life, rubbing shoulders with kings and politicians while at the same time laundering money for the mob through his legitimate business. -

Daring Deceit

FINAL-1 Sun, Oct 25, 2015 11:52:55 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of November 1 - 7, 2015 Daring deceit Priyanka Chopra INSIDE stars in “Quantico” •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Hollywood Q&A Page 3 •Family Favorites Page 4 The plot thickens as Alex Parrish (Priyanka Chopra, “Fashion,” 2008) struggles to prove she wasn’t behind a terrorist attack in New York City in a new episode of “Quantico,” airing Sunday, Nov. 1, on ABC. Flashbacks recount Parrish’s time at the FBI academy, where she trained alongside a diverse group of recruits. As the flashbacks unfold, it becomes clear that no one is what they seem, and everyone has something to hide. RICHARD’S New, Used&Vintage FURNITURE 0% Reclining SALE *Sofas *Love Seats *Sectionals *Chairs NO INTEREST ON LOANS *15% off Custom Orders Only! Group Page Shell Richards 5 x 3” at 1 x 3” CASH FOR GOLD Ends Nov14th Remember TRADE INS arewelcome 527 S. Broadway,Salem, NH www.richardsfurniture.com (On the Methuen Line above Enterprise Rent-A-Car) 25 WaterStreet 603-898-2580 •OPEN 7DAYSAWEEK Lawrence,MA WWW.CASHFORGOLDINC.COM 978-686-3903 FINAL-1 Sun, Oct 25, 2015 11:52:56 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights Kingston CHANNEL Atkinson Countdown to Green Live NESN Bruins Face-Off Live Sunday 8:00 p.m. (25) Baseball MLB World (7) Salem Londonderry Series Live (25) College Football Pre-game Live 7:00 p.m. ESPN Football NCAA Live Windham 9:00 a.m. (25) Fox NFL Sunday Live Sandown ESPN Basketball NBA New York Knicks ESPN College Football Scoreboard NESN Hockey NHL Boston Bruins at Pelham, 9:30 a.m. -

Student Data Leak Plugged

THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF MERCYHURST COLLEGE SINCE 1929 CAMPUS LIVING SPORTS “Love throughout the Women’s Hockey classes” one step closer to hosting playoffs Page 5 Page 12 Vol. 80 No. 15 Mercyhurst College 501 E. 38th St. Erie Pa. 16546 February 14, 2007 Student data leak plugged and personal information relating to The letter provides students with By Joshua Wilwohl Editor-in-chief you and several other students inad- phone numbers to three credit report- vertently was accessible via the Internet ing agencies and urges sophomores to to individuals inside and outside of the take the appropriate measures if suspi- Mercyhurst College administrators college.” cious activity is found. advised sophomores last week to file Director of Public Relations Meghan “If you do find suspicious activity on identity theft forms after their personal Corbin said the document containing your credit reports, call your local police information was discovered on a pub- the information could not be found by or sheriff ’s office and file a report of licly available section of the Mercyhurst a simple search on a public domain such identity theft,” states the letter. Web site. as Google or Yahoo. Some sophomores have mixed opin- According to Associate Vice President The letter says that a person would ions about the matter, but plan to take of Academic Service Mary Schultz, the have to search thoroughly to find the the steps to make sure their information information was accessible for almost information. is not compromised. two years until its discovery on Feb. 2 “Your information was not sent by e- Sophomore Kayla Lincoln says she by a nonstudent. -

Network Telivision

NETWORK TELIVISION NETWORK SHOWS: ABC AMERICAN HOUSEWIFE Comedy ABC Studios Kapital Entertainment Wednesdays, 9:30 - 10:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Katy Mixon as Katie Otto, Meg Donnelly as Taylor Otto, Diedrich Bader as Jeff Otto, Ali Wong as Doris, Julia Butters as Anna-Kat Otto, Daniel DiMaggio as Harrison Otto, Carly Hughes as Angela Executive producers: Sarah Dunn, Aaron Kaplan, Rick Weiner, Kenny Schwartz, Ruben Fleischer Casting: Brett Greenstein, Collin Daniel, Greenstein/Daniel Casting, 1030 Cole Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90038 Shoots in Los Angeles. BLACK-ISH Comedy ABC Studios Tuesdays, 9:00 - 9:30 p.m., returns Oct. 3 Cast: Anthony Anderson as Andre “Dre” Johnson, Tracee Ellis Ross as Rainbow Johnson, Yara Shahidi as Zoey Johnson, Marcus Scribner as Andre Johnson, Jr., Miles Brown as Jack Johnson, Marsai Martin as Diane Johnson, Laurence Fishburne as Pops, and Peter Mackenzie as Mr. Stevens Executive producers: Kenya Barris, Stacy Traub, Anthony Anderson, Laurence Fishburne, Helen Sugland, E. Brian Dobbins, Corey Nickerson Casting: Alexis Frank Koczaraand Christine Smith Shevchenko, Koczara/Shevchenko Casting, Disney Lot, 500 S. Buena Vista St., Shorts Bldg. 147, Burbank, CA 91521 Shoots in Los Angeles DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Drama ABC Studios The Mark Gordon Company Wednesdays, 10:00 - 11:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Kiefer Sutherland as Tom Kirkman, Natascha McElhone as Alex Kirkman, Adan Canto as Aaron Shore, Italia Ricci as Emily Rhodes, LaMonica Garrett as Mike Ritter, Kal Pennas Seth Wright, Maggie Q as Hannah Wells, Zoe McLellan as Kendra Daynes, Ben Lawson as Damian Rennett, and Paulo Costanzo as Lyor Boone Executive producers: David Guggenheim, Simon Kinberg, Mark Gordon, Keith Eisner, Jeff Melvoin, Nick Pepper, Suzan Bymel, Aditya Sood, Kiefer Sutherland Casting: Liz Dean, Ulrich/Dawson/Kritzer Casting, 4705 Laurel Canyon Blvd., Ste. -

The Disciples Divinity House of the University of Chicago

The Disciples Divinity House of the University of Chicago Vol. 89, No. 1 DDH Bulletin 125th Anniversary Edition Summer 2019 ture,” he explained. “Yet what is com- Celebrating 125 years ing is unknown…. Especially in days of such local and global crisis, anxiety, and suffering, how do we discern the future, not only with hope, but in- deed with gratitude? How can we now be grateful for what is to come?” (His remarks are published in this Bulletin.) Highlights of the weekend in- cluded a gala dinner at the Quadran- gle Club, with Masters of Ceremony Gaylord Yu and Drew Powell, film and television actor (Gotham, Pon- derosa, and Malcolm in the Middle). Chad Martin, Trustee Chair of the 125th Anniversary, Board of Trustees President April Lewton, and Dean Kris Culp spoke. Bringing greetings Over 250 alumni/ae, friends, and The theme for the weekend, were Divinity Dean David Nirenberg, current students gathered May 24-26 “Grateful for what is to come,” was Disciples General Minister and Presi- to celebrate DDH’s 125th anniver- enunciated by Larry Bouchard in a dent Teresa Hord Owens, Bill Blake- sary. Alums spanning six decades and keynote address. “We should be grate- more and Jory B. Johnson, and Heike friends from near and far traveled to ful for the Disciples House’s inspiring Springhart for the Theologisches Stu- Chicago for the celebration. history; but let our focus be the fu- (continued on page 4) Grateful for what is to come: $4M campaign for scholarships, internships, and accessibility As the Disciples Divinity House cel- “Plans for the 125th anniversary ebrates an historic 125th anniversary, have been in the works for five years,” we give thanks for its remarkable lega- explained Trustee Chad H. -

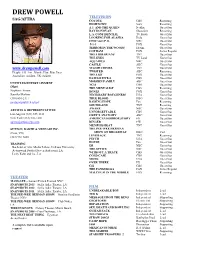

DREW POWELL TELEVISION SAG/AFTRA COYOTE CBS Recurring HIGHTOWN Starz Recurring A.J

DREW POWELL TELEVISION SAG/AFTRA COYOTE CBS Recurring HIGHTOWN Starz Recurring A.J. AND THE QUEEN Netflix Guest Star RAY DONOVAN Showtime Recurring L.A. CONFIDENTIAL TV Movie Guest Star LOOKING FOR ALASKA Hulu Guest Star CHICAGO P.D. NBC Guest Star 9-1-1 FOX Guest Star TERROR IN THE WOODS lifetime Guest Star GOTHAM FOX Series Regular THE LIBRARIANS TNT Guest Star THE EXES TV Land Guest Star AQUARIUS NBC Guest Star CASTLE ABC Guest Star www.drewpowell.com MAJOR CRIMES TNT Guest Star Height: 6 ft. 3 in., Blonde Hair, Blue Eyes TWISTED ABC Recurring Australian resident, UK resident THE LIST FOX Guest Star HAWAII FIVE-0 CBS Guest Star MODERN FAMILY ABC Guest Star UNTITLED ENTERTAINMENT NCIS CBS Guest Star (Mgr) THE MENTALIST CBS Recurring Stephanie Simon BONES FOX Guest Star Jennifer Merlino WIDOW DETECTIVE ABC Guest Star (310) 601-2111 NECESSARY ROUGHNESS USA Guest Star [email protected] TRUE BLOOD HBO Guest Star RAISING HOPE Fox Recurring SOUTHLAND TNT Recurring ARTISTS & REPRESENTATIVES AWAKE NBC Guest Star Los Angeles (323) 655-1313 UNFORGETTABLE CBS Guest Star New York (212) 505-1400 GREY’S ANATOMY ABC Guest Star [email protected] AMERICAN HORROR STORY FX Guest Star RINGER CW Guest Star SUTTON, BARTH & VENNARI INC. MENPHIS BEAT TNT Guest Star (Com, VO) THE PEE-WEE HERMAN SHOW ON BROADWAY HBO Cast (323) 938-6000 IN PLAIN SIGHT USA Guest Star LEVERAGE TNT Recurring TRAINING PSYCH USA Guest Star Bachelor of Arts, Media Fellow, DePauw University HOUSE Fox Guest Star Actorswork Studio (Steven Anderson), LA ER NBC Guest Star Lesly -

Review Copycopy

From Grave to Cradle Now A father’s fi rst-person account From Grave to Using the collaterally damaged family as a lifesaving and healing instrument. Cradle to Now Ian Powell has been CEO of various enterprises, A father’s first hand account entrepreneur, assistant to a federal cabinet minister, management consultant and president of a national practice group for a major international accounting and consulting rm. He has given numerous addresses For Doctors, Nurses, Therapists, including to industry, investment and human resources conferences, law and business schools, as well as addressing Educators, Patients, Families, committees of both Houses of the US Congress. Friends, Human Resources … “… it is captured as a whole lived experience, including the explainable, the frightening, the joyful and the mysterious. It is the story before analysis, before explanation and before the extraction of "useful" guidance for professionals that captures the heart. Read the words, see his family and yours and marvel at your good fortune to have this account. Learning will follow.” The Health Care Professional Edition David A. Gass, MD, CCFP, FCFP , Professor, Department of Family Medicine Dalhousie University “… book of compelling nature, capturing attention, giving goose bumps at times…. We can all identify with it. e anguish and struggle of its characters to be better, to do better, to reach higher is a recipe for ongoing spiritual growth of everyone who is intent on growing and a reminder to those who are missing the opportunity.” Dr. J. N. Vanek, MD, Psychotherapist REVIEWREVIEW COPYCOPY Publishing Marrette The Health Care Professional Edition Marrette Publishing www.facebook.com/FromGraveToCradle www.marrette.cc/publishing.html REVIEW COPY “Your loved one has just suffered a traumatic brain injury” - these are words that are certain to cause dread and tremendous anxiety for any family. -

Gstar-072807-A-01.Qxd

NORTHEAST FLORIDA’S OLDEST, LARGEST, MOST READ AFRICAN AMERICAN OWNED NEWSPAPER The Florida Star Presorted Standard CRIME and The Florida Star, P. O. Box 40629 U.S. Postage Paid INSIDE FREE TICKETS Jacksonville, FL 32203 Jacksonville, FL JUSTICE The Georgia Star! Permit No. 3617 Women’s (904) 766-8834 Can’t Get to the Store Conference Still Number One! Striving to make Have The Star Delivered Vickie Winans a difference An Award Read The Florida Winning and Georgia Star Publication, Newspapers. Listen to IMPACT serving you Radio Talk Show. since 1951. WWW.thefloridastar.com Rated “A” by The people’s choice the Better Business Bureau www.thefloridastar.com SEPTEMBER 22 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2012 VOL. 62 NO. 23 50 CENTS Her Quick Death, His Slow Arrest WHY VOTE? Rinetta McLaughlin Fefie For the Jacksonville, the 137,000 Names Removed from arrest of Ismet for the death of the beautiful teenager, Florida’s Voter Roll -10,000 Pages JaNay Jackson, while she slept, was far too long. Floridians, you should be concerned, wake up! There are 137,000 names removed Det. R.D. Peck, who has since the 2008 election from Duval County’s Voter Roll. been with the Jacksonville Congresswoman Corrine Brown has scheduled registration on National Sheriff's Office for ten Registration Day at the Duval County Supervisor of Election office, located at 105 years, and a traffic homi- East Monroe Street on Tuesday, September 25, 2012 so all who do or do not under- cide detective for five stand the serious situation we are about to face. Presidential candidate, Mitt Romney said on March 13, 2012 (it was recorded), Ismet Sijamphodzic years, investigated the crash involving a fatality. -

Parachute G I R L S

PARACHUTE G I R L S THE PILSEN NATION PRESENTS PARACHUTE GIRLS A HEADFOOT PRODUCTION DIRECTOR OF PHOTORAPHY ALEJANDRO WILKINS EDITOR TODD ZELIN PRODUCED BY PRADEEPA JEEVA EXECUTIVE PRODUCER EMILY C. CHANG CO-PRODUCED BY MAITELY WEISMANN AND MURTAZA AKBAR ASSOCIATE PRODUCERS HAYDEN SCHOLASSBERG, CHI-KAI KING, ABIGAIL BRADEN MATT SWAIN, KARTHIK SELVAKUMAR, JUSTIN SEVAKIS PRODUCTION DESIGNER DAVID HARRY YOON MUSIC BY GOH NAKAMURA WRITTEN BY EMILY C. CHANG DIRECTED BY ALEX RUBENS CONTACT ~ Emily C. Chang :: www.parachutegirlsfilm.com :: [email protected] 646.373.2443 PARACHUTE G I R L S Genre Drama Logline A woman shows up at her sister's dinner party after years of no contact and threatens to reveal family secrets to the guests. Synopsis (short) Two estranged sisters essentially abandoned as children by their parents are reunited when Ellie, the younger sister, crashes older sis Evelyn's dinner party and begins to destroy Evelyn's suburban illusion of the perfect family. Social Media Links Official Twitter: @paragirlsfilm Official Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/paragirlsfilm Producer/Writer/Actress Emily C. Chang: Twitter: @chihuac Director Alex Rubens: Twitter: @atrubens Co-star Lynn Chen: Twitter: @mslynnchen CONTACT ~ Emily C. Chang :: www.parachutegirlsfilm.com :: [email protected] 646.373.2443 PARACHUTE G I R L S Bios Emily C. Chang :: Actress/Writer/Producer Emily C. Chang is an Emmy Award-winning performer and writer who was born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and grew up in New Jersey. She most recently recurred as Ivy on the CW's Vampire Diaries, as well as other guest starring roles on Community, How I Met Your Mother, Bones, Intelligence, Days of Our Lives, NCIS, The Young & The Restless, 90210, and Brothers and Sisters, and the recent remake of the classic sci-fi movie, Total Recall. -

Published Bi-Monthly Volume 29 • No. 4 August/September 2018

PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY VOLUME 29 • NO. 4 AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2018 NON-SPORT UPDATE Aug.-Sept. 2018 • u.S. $5.99 • CAN. $6.49 Issue Code: 2018-08 • Display until 10/16/18 PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. 08 0 71486 02957 1 VOLUME 29 • NO. 4 AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2018 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS OUR STAFF 4 CARDBOARD CONVERSATION: 6 PROMO PICKS EDITORIAL DIRECTOR - Mike Payne ROLLING IN DʼOH! “Whatever, Iʼll be at Moeʼs.” 8 NON-SPORT NEIGHBORHOOD: EDITOR-IN-CHIEF - Alan Biegel MEET MICHAEL BEAM 10 TRUE LOVE IS NEVER LOST Time to Beam up with this PRODUCTION MANAGER - Harris Toser What if your future was the past? experienced card collector. Find out with Outlander Season 3. ART DIRECTOR - Lindsey Jones 26 NEW & NOTEWORTHY GRAPHIC DESIGN - Eric Knagg, Chris Duncan 16 VINTAGE SPOTLIGHT: LOVE ME DO Classic Mythology III: Goddesses, COLLECTIBLES DATA PUBLISHING Get a ticket to ride with this Beatles beauty. Topps Star Wars Archives Signatures, Manager, Senior Market Analyst - Brian Fleischer 22 STAR TREK: THE ORIGINAL DC Bombshells Trading Cards II. SERIES CAPTAINʼS COLLECTION 28 DATELINE PRICE GUIDE STAFF: Jeff Camay, Arsenio Tan, Captain on the bridge for this new Lloyd Almonguera, Kristian Redulla, Justin Grunert, Matt 30 NON-SPORT NEWS compilation from Rittenhouse. Bible, Eric Norton, Irish Desiree Serida, Paul Wirth, Ian 32 DANGER, WILL ROBINSON! 38 THE HOT LIST McDaries, Sam Zimmer, Steve Dalton Jump aboard the Jupiter 2 for a 41 HOW TO USE THE PRICE GUIDE WRITERS: Arnold Bailey, Matt Bible, Alan Biegel, wild non-sport ride. 42 PRICE GUIDE Ryan Cracknell, Don Norton, Charlie Novinskie, Rudy Panucci, Harris Toser, Chick Veditz Non-Sport Update (ISSN: 10598383) is Beckett Collectibles Inc. -

SCC Grant to Connect Unemployed with Jobs

rSCHS blanks Eagles to advance to Eastern 2A fnals. r7JLJOHTUPPQFOIPPQTTFBTPOUPOJHIU Sports 4FFQBHF# ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Tursday forReporter the County of Columbus and her people. Monday, November 21, 2011 Ofcials Furloughs, pay Volume 121, Number 41 cite need cuts for aging Whiteville, North Carolina for fu shots considered 75 Cents By RAY WYCHE Staff Writer By NICOLE CARTRETTE Staff Writer The week of Dec. 4-10 has Inside Today been declared National In- Curbing financial losses at the Columbus fluenza Vaccination Week, County Department of Aging may come in 4-A according to information re- the form of furloughs for full-time employees r8PNBOêSFTTIPU ceived by the local county but nurse aides still face significant pay cuts. health department. In his latest recommendation to reduce the BUCVSHMBS Columbus County Health shortfall at the department, County Manager Department Director Kim Bill Clark in an email Friday to commissioners Smith emphasized the need for and others recommends a 15-hour per month residents to receive the immu- furlough for all full-time employees at the de- DIDYOB? nization and issued a reminder partment for the remainder of the fiscal year. Did you observe ... to people that “we are in the Those brief unpaid leaves of absence paired beginning of the season when with an 8 percent cut to all nurse aides will influenza cases are most likely still leave the department with a shortfall for Jubilant South Co- to occur. the second consecutive fiscal year but a much lumbus football “We will give flu vaccina- smaller one than last year. -

DREW POWELL TELEVISION SAG/AFTRA COYOTE CBS Recurring HIGHTOWN Starz Recurring A.J

DREW POWELL TELEVISION SAG/AFTRA COYOTE CBS Recurring HIGHTOWN Starz Recurring A.J. AND THE QUEEN Netflix Guest Star RAY DONOVAN Showtime Recurring L.A. CONFIDENTIAL TV Movie Guest Star LOOKING FOR ALASKA Hulu Guest Star CHICAGO P.D. NBC Guest Star 9-1-1 FOX Guest Star TERROR IN THE WOODS lifetime Guest Star GOTHAM FOX Series Regular THE LIBRARIANS TNT Guest Star THE EXES TV Land Guest Star AQUARIUS NBC Guest Star CASTLE ABC Guest Star www.drewpowell.com MAJOR CRIMES TNT Guest Star Height: 6 ft. 3 in., Blonde Hair, Blue Eyes TWISTED ABC Recurring Australian resident, UK resident THE LIST FOX Guest Star HAWAII FIVE-0 CBS Guest Star MODERN FAMILY ABC Guest Star UNTITLED ENTERTAINMENT NCIS CBS Guest Star (Mgr) THE MENTALIST CBS Recurring Stephanie Simon BONES FOX Guest Star Jennifer Merlino NECESSARY ROUGHNESS USA Guest Star (310) 601-2111 TRUE BLOOD HBO Guest Star [email protected] RAISING HOPE Fox Recurring SOUTHLAND TNT Recurring AWAKE NBC Guest Star ARTISTS & REPRESENTATIVES UNFORGETTABLE CBS Guest Star Los Angeles (323) 655-1313 GREY’S ANATOMY ABC Guest Star New York (212) 505-1400 AMERICAN HORROR STORY FX Guest Star [email protected] RINGER CW Guest Star MEMPHIS BEAT TNT Guest Star SUTTON, BARTH & VENNARI INC. THE PEE-WEE HERMAN (Com, VO) SHOW ON BROADWAY HBO Cast LEVERAGE TNT Recurring (323) 938-6000 PSYCH USA Guest Star HOUSE Fox Guest Star TRAINING ER NBC Guest Star Bachelor of Arts, Media Fellow, DePauw University THE OFFICE NBC Guest Star Actorswork Studio (Steven Anderson), LA WITHOUT A TRACE CBS Guest Star Lesly