The Hague As the Seat of the Lockerbie Trial: Some Constraints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lockerbie "Extradition by Analogy" Agreement: "Exceptional Measure" Or Template for Transnational Criminal Justice? Donna E

American University International Law Review Volume 18 | Issue 1 Article 4 2002 The Lockerbie "Extradition by Analogy" Agreement: "Exceptional Measure" or Template for Transnational Criminal Justice? Donna E. Arzt Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Arzt, Donna E. "The Lockerbie "Extradition by Analogy" Agreement: "Exceptional Measure" or Template for Transnational Criminal Justice?" American University International Law Review 18, no. 1 (2002): 163-236. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LOCKERBIE "EXTRADITION BY ANALOGY" AGREEMENT: "EXCEPTIONAL MEASURE" OR TEMPLATE FOR TRANSNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE? DONNA E. ARZT* INTRODU CTION .............................................. 164 I. THE EXTRADITION LACUNA ............................ 172 II. THE SECRETARY-GENERAL'S INTERVENTION ........ 179 A. PRE-TRIAL DEVELOPMENTS .............................. 179 B. THE "GOOD OFFICES" FUNCTION ......................... 186 C. THE 17 FEBRUARY 1999 "LETTER OF UNDERSTANDING" .. 193 1. Context and Cover Letter ............................. 194 2. The Letter's Annex -

BUTLER LAND MANAGEMENT LTD Newhall Farm, Tundergarth, Lockerbie for Sale Privately

BUTLER LAND MANAGEMENT LTD 01461 201200 butlerlm.co.uk Newhall Farm, Tundergarth, Lockerbie A productive stock farm extending to around 111.87ha (276.41ac) For Sale Privately on the instructions of Mr E Halliday Location Newhall Farm is situated just off the B7068 along an unclassified road. Lockerbie and Langholm are easily accessible, approximately 7 and 11 miles respectively along this road. There are good transport links to both North and South via the M74 at Eaglesfield or Lockerbie. Glasgow is only 1hour and 30mins by car. Local amenities and schools are nearby in the towns of Lockerbie and Langholm. Bankshill and Eaglesfield have small primary schools. Productive Stock Farm in an accessible location Accommodation The property affords the following accommodation:- Entrance Hall Utility Room (3.9m x 1.94m) Washing Machine, Tumble dryer and sink Sitting Room (4.9m x 4.5m) LPG Gas Fireplace Kitchen (4.05m x 2.6m) Electric cooker and fitted units Bathroom (2.8m x 3m) Four piece suite in white Bedroom 1 (3.75m x 3.3m) Built in wardrobe Bedroom 2 (4.07m x 2.45m) Built in cupboard Bedroom 3 (4.07m x 2.55m) Built in cupboard Attic Garden Easily maintained gravel garden with well stocked borders on three sides. Council Tax We are informed that the property is assessed as Band C for Council Tax purposes. Steading The Steading comprises of both traditional and modern buildings. Traditional Steading Former hay shed (5.25m x 15.9m) Workshop (15.2m x 5.15m) Modern Steading Polytunnel (9.3m x 36m) o Used as former lambing shed Cattle -

Report on the Current Position of Poverty and Deprivation in Dumfries and Galloway 2020

Dumfries and Galloway Council Report on the current position of Poverty and Deprivation in Dumfries and Galloway 2020 3 December 2020 1 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. National Context 2 3. Analysis by the Geographies 5 3.1 Dumfries and Galloway – Geography and Population 5 3.2 Geographies Used for Analysis of Poverty and Deprivation Data 6 4. Overview of Poverty in Dumfries and Galloway 10 4.1 Comparisons with the Crichton Institute Report and Trends over Time 13 5. Poverty at the Local Level 16 5.1 Digital Connectivity 17 5.2 Education and Skills 23 5.3 Employment 29 5.4 Fuel Poverty 44 5.5 Food Poverty 50 5.6 Health and Wellbeing 54 5.7 Housing 57 5.8 Income 67 5.9 Travel and Access to Services 75 5.10 Financial Inclusion 82 5.11 Child Poverty 85 6. Poverty and Protected Characteristics 88 6.1 Age 88 6.2 Disability 91 6.3 Gender Reassignment 93 6.4 Marriage and Civil Partnership 93 6.5 Pregnancy and Maternity 93 6.6 Race 93 6.7 Religion or Belief 101 6.8 Sex 101 6.9 Sexual Orientation 104 6.10 Veterans 105 7. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Poverty in Scotland 107 8. Summary and Conclusions 110 8.1 Overview of Poverty in Dumfries and Galloway 110 8.2 Digital Connectivity 110 8.3 Education and Skills 111 8.4 Employment 111 8.5 Fuel Poverty 112 8.6 Food Poverty 112 8.7 Health and Wellbeing 113 8.8 Housing 113 8.9 Income 113 8.10 Travel and Access to Services 114 8.11 Financial Inclusion 114 8.12 Child Poverty 114 8.13 Change Since 2016 115 8.14 Poverty and Protected Characteristics 116 Appendix 1 – Datazones 117 2 1. -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY South West Scotland Transport Study: Initial Appraisal Case for Change

January 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY South West Scotland Transport Study: Initial Appraisal Case for Change Executive Summary Background In the 2017/18 Programme for Government, the Scottish Government committed to commence work for the second Strategic Transport Projects Review (STPR2) in the Dumfries and Galloway area. Responding to this commitment, AECOM and Stantec were commissioned to carry out the first stage in the Scottish Transport Appraisal Guidance (STAG) process, researching the case for investment in potential transport interventions in the South West of Scotland through an Initial Appraisal: Case for Change study. The key aim of the work is to consider the rationale for improvements to road, rail, public transport and active travel on key strategic corridors in the South West of Scotland, including those served by the A75 and A77, with a focus on access to the ports at Cairnryan. The study area includes Dumfries & Galloway and the southern extents of South Ayrshire and East Ayrshire and has focused on the following strategic corridors: • Gretna – Stranraer • South of Ayr – Stranraer • Dumfries – Cumnock Figure 1: South West Scotland Transport Study - Study Area • Dumfries – Lockerbie and Moffat Approach The Initial Appraisal: Case for Change constitutes the first stage of STAG and involves the following core tasks: • Analysis of Problems and Opportunities: Establish the evidence base for problems and issues linked to transport on key corridors across the South West of Scotland drawing on targeted data analysis and engagement with the public and key stakeholders; • Objective Setting: Develop initial Transport Planning Objectives to encapsulate the aims of any interventions and to guide the development of solutions; and • Option Generation, Sifting and Development: Develop a long list of multi-modal options to address the identified problems and opportunities, and undertake a process of option sifting and development leading to the identification of a short list of interventions recommended for progression towards Preliminary Appraisal. -

Lockerbie Academy Handbook (Updated for 2021)

Welcome to Lockerbie Academy Handbook (updated for 2021) Dumfries and Galloway Education Services Lockerbie Academy Handbook 2021 Welcome to our handbook for 2021, where you should find all the information required by the Education (School and Placing Information) (Scotland) Regulations 2012. A printed copy of this handbook is available from the school office. We have endeavoured to provide information that is correct and accurate at this time, but please do not hesitate to raise any queries with us. If your child is presently attending the school then you should find that the information routinely provided negates the need for this document, from your point of view. Lockerbie Academy is, however, careful to present this information, and more, to families and to our community, in an accessible fashion and scale, and at appropriate times. We find this leads to effective dialogue with our parents, which is of paramount importance to us. Another point of contact for information on our school is our website; www.lockerbieacademy.dumgal.sch.uk Dumfries and Galloway Education Services Contents 1. Letter from Director of Education 2 Welcome from the Rector 3. Authority Aims 4. School Vision, Values and Aims 5. School Ethos 6. School Information 6.1 Name/Address/Telephone No/Website /Email Address 6.2 Rector 6.3 A Brief History of the School 6.4 School Staff 6.5 Terms and Holidays 7. School Contacts 7.1 Pupil Support 7.2 If you have a complaint 8. How the School Works 8.1 School Day 8.2 School Uniform/Dress Policy 8.3 School Meals 8.4 School Transport 8.5 Class organisation 8.6 Positive Behaviour and Celebrating Success 9. -

The Beeches Corse Hill, Haugh of Urr, Castle Douglas OFFICES ACROSS SCOTLAND the Beeches Corse Hill, Haugh of Urr Castle Douglas

THE BEECHES CORSE HILL, HAUGH OF URR, CASTLE DOUGLAS OFFICES ACROSS SCOTLAND THE BEECHES CORSE HILL, HAUGH OF URR CASTLE DOUGLAS Castle Douglas 3 miles Dalbeattie 3 miles Dumfries 13 miles. A beautiful architect designed bungalow in an elevated position on the edge of a sought after village. Accommodation on a single level comprises: • Entrance Vestibule. Hallway. Open plan Sitting & Dining Room. Kitchen. Utility Room. • Bedroom /Study. Guest Bedroom. Master Bedroom Suite. Integral Garage. Family Bathroom. • Disabled Access • Security System • Garden CKD Galbraith Castle Douglas Property Department 120 King Street Castle Douglas DG7 1LU Tel: 01556 505346 Fax: 01556 503729 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ckdgalbraith.co.uk GENERAL In addition, Kirkcudbright is the local Artists town The Beeches sits on the edge of the quiet Galloway with a number of galleries offering a range of art village of Haugh of Urr, which is tucked away in exhibitions throughout the year, and individual rolling countryside, yet centrally situated between shops. Communications to the area are very good. two small towns, and within easy reach of the A75 There is a main line railway station in Dumfries and trunk road. From the house itself, circuit walks also Lockerbie providing excellent links to both around the village of either 2 miles or 4 miles can the north and south. The M74 motorway network be enjoyed, and the village has a popular pub is approximately 30 miles distant, and there are which also serves meals. A village primary school is regular flights to other parts of the UK, Ireland and available just up the hill in Hardgate, a neighbouring Continental Europe from Prestwick Airport about hamlet. -

Flood Risk Management Strategy Solway Local Plan District Section 3

Flood Risk Management Strategy Solway Local Plan District This section provides supplementary information on the characteristics and impacts of river, coastal and surface water flooding. Future impacts due to climate change, the potential for natural flood management and links to river basin management are also described within these chapters. Detailed information about the objectives and actions to manage flooding are provided in Section 2. Section 3: Supporting information 3.1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 31 1 3.2 River flooding ......................................................................................... 31 2 • Esk (Dumfriesshire) catchment group .............................................. 31 3 • Annan catchment group ................................................................... 32 1 • Nith catchment group ....................................................................... 32 7 • Dee (Galloway) catchment group ..................................................... 33 5 • Cree catchment group ...................................................................... 34 2 3.3 Coastal flooding ...................................................................................... 349 3.4 Surface water flooding ............................................................................ 359 Solway Local Plan District Section 3 310 3.1 Introduction In the Solway Local Plan District, river flooding is reported across five distinct river catchments. -

Proposed Plan

Dumfries and Galloway Council LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2 Proposed Plan JANUARY 2018 www.dumgal.gov.uk Please call 030 33 33 3000 to make arrangements for translation or to provide information in larger type or audio tape. Proposed Plan The Proposed Plan is the settled view of Dumfries and Galloway Council.Copiesof the Plan and supporting documents can be viewed at all Council planning offices, local libraries and online at www.dumgal.gov.uk/LDP2 The Plan along with its supporting documents is published on 29 January 2018 for eight weeks during which representations can be made. Representations can be made to the Plan and any of the supporting documents at any time during the representation period. The closing date for representations is 4pm on $SULO 2018. Representations received after the closing date will not be accepted. When making a representation you must tell us: • What part of the plan your representation relates to, please state the policy reference, paragraph number or site reference; • Whether or not you want to see a change; • What the change is and why. Representations made to the Proposed Plan should be concise at no more than 2,000 words plus any limited supporting documents. The representation should also fully explain the issue or issues that you want considered at the examination as there is no automatic opportunity to expand on the representation later on in the process. Representations should be made using the representation form. An online and pdf version is available at www.dumgal.gov.uk/LDP2 , paper copies are also available at all Council planning offices, local libraries and from the development plan team at the address below. -

KNOCKMAINS Langholm Road, Lockerbie, DG11 2PH Location Plan

KNOCKMAINS Langholm Road, Lockerbie, DG11 2PH Location Plan NOT TO SCALE Plan for indicative purposes only KNOCKMAINS Langholm Road, Lockerbie, DG11 2PH Dumfries 13 miles, Carlisle 29 miles, Glasgow 72 Miles, Edinburgh 74 Miles AN ATTRACTIVE TRADITIONAL DUMFRIESSHIRE PROPERTY SITUATED ON AN ELEVATED SITE BENEFITTING FROM A DETACHED JOINERS WORKSHOP • TRADITIONAL DETACHED THREE BEDROOM DWELLINGHOUSE • PRIVATE ELEVATED SITE WITH OPEN VIEWS OVER THE SURROUNDING COUNTRYSIDE • DETACHED JOINERS WORKSHOP • WITHIN CLOSE PROXIMITY TO MAJOR ROAD NETWORKS • EPC – E47 FOR SALE PRIVATELY VENDORS SOLICITORS SOLE SELLING AGENTS McJerrow & Stevenson Threave Rural 55 High St The Rockcliffe Suite Lockerbie The Old Exchange DG11 2JJ Castle Douglas Tel: 01576 202123 DG7 1TJ Tel: 01556 453 453 Email: [email protected] Web: www.threaverural.co.uk INTRODUCTION GUIDE PRICE Knockmains is located just on the outskirts of the busy market town of Lockerbie. Offers for Knockmains are sought in excess of: £295,000 This traditional Dumfriesshire dwelling is situated on a private elevated site and VIEWING benefits from a semi-rural countryside location. The property has been utilised as By appointment with the sole selling agents: a family home over the years and includes the joiners workshop, which has been the family business for three generations. Knockmains retains many of the original Threave Rural features and with the inclusion of the detached buildings, this unique property would The Rockcliffe Suite allow any purchaser to develop a business within the catchment of the busy market The Old Exchange town of Lockerbie. Castle Douglas, DG7 1TJ Tel: 01556 453453 Local services are found within the busy market town of Lockerbie, which offers all Email: [email protected] essential services with a comprehensive range of leisure facilities, a modern health Web: www.threaverural.co.uk centre, a wide range of professional services as well as two national supermarkets. -

The Lockerbie Terrorist Attack and Libya: a Retrospective Analysis Steve Emerson

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 36 | Issue 2 2004 The Lockerbie Terrorist Attack and Libya: A Retrospective Analysis Steve Emerson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Steve Emerson, The Lockerbie Terrorist Attack and Libya: A Retrospective Analysis, 36 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 487 (2004) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol36/iss2/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE LOCKERBIE TERRORIST ATTACK AND LIBYA: A RETROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS* Steve Emersont Following the horrific terrorist crime that saw Pan Am flight 103 literally blown out of the sky, an incredible journey of forensic investigations and intelligence began that ultimately resulted in a momentous court verdict in 2001. The forensic investigation alone into Pan Am 103, was one of the most intense, meticulous and expensive criminal investigations ever undertaken. As many will recall, the initial theory was that Iran had effectively "subcontracted" this murderous project to Syria and Libya in retaliation for the U.S. downing of an Iranian jet. In fact, in the months before the Pan Am 103 bombing, a Syrian cell possessing barometric bombs had been arrested in Frankfurt. It was thought at the time that these bombs were to be placed on aircraft departing from Frankfurt to Britain. -

Weekly List of Decisions List of Planning Application Decisions Issued 31 May 2021 - 4 June 2021

PUBLIC Steve Rogers – Head of Economy and Development Kirkbank, English Street, Dumfries, DG1 2HS Telephone (01387) 260199 - Fax (01387) 260188 Weekly List of Decisions List of Planning Application Decisions issued 31 May 2021 - 4 June 2021 For information regarding applications please contact the case officer. Depending on the decision route, decisions may be subject to review by the Council’s Local Review Body or subject to an appeal to Scottish Ministers. List Issue Date: 9 June 2021 Application Date of Date Of Decision Applicant Agent Location Proposal Ward Officer Number Validation Decision OS Grid Ref. 20/1795/FUL 17.12.2020 01.06.2021 Grant Mr Clifford Building Little CONVERSION OF Stranraer Iona Conditionally Howe Design (UK) Cairnbrock ACCOMMODATION And The Brooke The Cottage Limited Ervie BLOCK Rhins Low Street Tayson Leswalt PREVIOUSLY Brotherton House APPROVED UNDER E:197848 Knottingley Methley Road APPLICATION NO. N:566670 WF11 9HQ Castleford 13/P/1/0430 WF10 1PA (IMPLEMENTED ON 21/05/2014) TO 3 NO. DETACHED DWELLINGS 1 PUBLIC PUBLIC Application Date of Date Of Decision Applicant Agent Location Proposal Ward Officer Number Validation Decision OS Grid Ref. 21/0067/FUL 11.03.2021 04.06.2021 Grant Mr Philip WBC Plot 4 ERECTION OF Stranraer Mary Conditionally Harrington Drawings South Cliff DWELLINGHOUSE And The Mitchell Waterside Lockside Portpatrick AND GARAGE Rhins House 38 Leigh Stranraer BUILDING AND Pincock Street DG9 8LE FORMATION OF E:200021 Street Wigan ACCESS N:553886 Euxton WN1 3BE PR7 6LR 21/0844/FUL 26.04.2021 03.06.2021 -

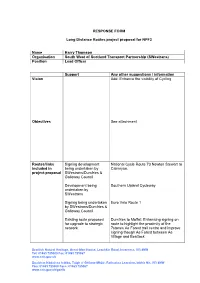

Swestransresponse NPF3 Project Proposal

RESPONSE FORM Long Distance Routes project proposal for NPF3 Name Harry Thomson Organisation South West of Scotland Transport Partnership (SWestrans) Position Lead Officer Support Any other suggestions / information Vision Add: Enhance the visibility of Cycling Objectives See attachment Routes/links Signing development National Cycle Route 73 Newton Stewart to included in being undertaken by Cairnryan. project proposal SWestrans/Dumfries & Galloway Council Development being Southern Upland Cycleway undertaken by SWestrans Signing being undertaken Euro Velo Route 1 by SWestrans/Dumfries & Galloway Council Existing route proposed Dumfries to Moffat: Enhancing signing on for upgrade to strategic route to highlight the proximity of the network 7stanes Ae Forest trail centre and improve signing though Ae Forest between Ae Village and Beattock Scottish Natural Heritage, Great Glen House, Leachkin Road, Inverness, IV3 8NW Tel: 01463 725000 Fax: 01463 725067 www.snh.gov.uk Dualchas Nàdair na h-Alba, Taigh a’ Ghlinne Mhòir, Rathad na Leacainn, Inbhir Nis, IV3 8NW Fòn: 01463 725000 Facs: 01463 725067 www.snh.gov.uk/gaelic Project being undertaken NCR 7: Enhanced connectivity to Dumfries by Dumfries & Galloway town Centre and Railway Station also Council provides connectivity to Dumfries-Moffat and the local route from Dumfries to Mabie Forest (7Stanes mountain bike trail centre). This route when complete will allow visitors to access the trails by train from Central Scotland and Northern England. The route will also provide an alternative route via a number of tourist destinations, New Abbey, Rockcliff, Dalbeattie, etc. to NCR7 west of dumfries. Proposed for future Dumfries-Lockerbie. Part exists. Part in national network – more Regional Transport Strategy.