Great Victoria Desert SA 2017, a Bush Blitz Survey Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gliding Dragons and Flying Squirrels: Diversifying Versus Stabilizing Selection on Morphology Following the Evolution of an Innovation

vol. 195, no. 2 the american naturalist february 2020 E-Article Gliding Dragons and Flying Squirrels: Diversifying versus Stabilizing Selection on Morphology following the Evolution of an Innovation Terry J. Ord,1,* Joan Garcia-Porta,1,† Marina Querejeta,2,‡ and David C. Collar3 1. Evolution and Ecology Research Centre and the School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Kensington, New South Wales 2052, Australia; 2. Institute of Evolutionary Biology (CSIC–Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, 37–49, Barcelona 08003, Spain; 3. Department of Organismal and Environmental Biology, Christopher Newport University, Newport News, Virginia 23606 Submitted August 1, 2018; Accepted July 16, 2019; Electronically published December 17, 2019 Online enhancements: supplemental material. Dryad data: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.t7g227h. fi abstract: Evolutionary innovations and ecological competition are eral de nitions of what represents an innovation have been factors often cited as drivers of adaptive diversification. Yet many offered (reviewed by Rabosky 2017), this classical descrip- innovations result in stabilizing rather than diversifying selection on tion arguably remains the most useful (Galis 2001; Stroud morphology, and morphological disparity among coexisting species and Losos 2016; Rabosky 2017). Hypothesized innovations can reflect competitive exclusion (species sorting) rather than sympat- have drawn considerable attention among ecologists and ric adaptive divergence (character displacement). We studied the in- evolutionary biologists because they can expand the range novation of gliding in dragons (Agamidae) and squirrels (Sciuridae) of ecological niches occupied within communities. In do- and its effect on subsequent body size diversification. We found that gliding either had no impact (squirrels) or resulted in strong stabilizing ing so, innovations are thought to be important engines of selection on body size (dragons). -

Making a Meeting Place Eucalypt Trail Map and Signs

Friends of the Australian National Botanic Gardens Number 73 April 2013 Inside: Making a Meeting Place Eucalypt Trail map and signs Friends of the Australian National Botanic Gardens Patron His Excellency Mr Michael Bryce AM AE Vice Patron Mrs Marlena Jeffery President David Coutts Vice President Barbara Podger Secretary John Connolly Treasurer Marion Jones Public Officer David Coutts General Committee Dennis Ayliffe Glenys Bishop Anne Campbell Lesley Jackman Warwick Wright Talks Convenor Lesley Jackman Membership Secretary Barbara Scott Fronds Committee Margaret Clarke Barbara Podger Anne Rawson Growing Friends Kath Holtzapffel Botanic Art Groups Helen Hinton Photographic Group Graham Brown Social events Jan Finley Exec. Director, ANBG Dr Judy West Post: Friends of ANBG, GPO Box 1777 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Telephone: (02) 6250 9548 (messages) Internet: www.friendsanbg.org.au Email addresses: [email protected] IN THIS ISSUE [email protected] [email protected] Eucalypt Trail map and signs.................................................2 Fronds is published three times a year. We welcome your articles for inclusion in the next Discover eucalypts ................................................................3 issue. Material should be forwarded to the Giant wood moths in the Gardens .........................................4 Fronds Committee by mid-February for the April issue; mid-June for the August issue; Growing Friends ....................................................................6 mid-October -

Ngaanyatjarra Central Ranges Indigenous Protected Area

PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the NGAANYATJARRA LANDS INDIGENOUS PROTECTED AREA Ngaanyatjarra Council Land Management Unit August 2002 PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the Ngaanyatjarra Lands Indigenous Protected Area Prepared by: Keith Noble People & Ecology on behalf of the: Ngaanyatjarra Land Management Unit August 2002 i Table of Contents Notes on Yarnangu Orthography .................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................................................ v Cover photos .................................................................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................................. v Summary.................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Transline Infrastructure Corridor Vegetation and Flora Survey

TROPICANA GOLD PROJECT Tropicana – Transline Infrastructure Corridor Vegetation and Flora Survey 025 Wellington Street WEST PERTH WA 6005 phone: 9322 1944 fax: 9322 1599 ACN 088 821 425 ABN 63 088 821 425 www.ecologia.com.au Tropicana Gold Project Tropicana Joint Venture Tropicana-Transline Infrastructure Corridor: Vegetation and Flora Survey July 2009 Tropicana Gold Project Tropicana-Transline Infrastructure Corridor Flora and Vegetation Survey © ecologia Environment (2009). Reproduction of this report in whole or in part by electronic, mechanical or chemical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, in any language, is strictly prohibited without the express approval of ecologia Environment and/or AngloGold Ashanti Australia. Restrictions on Use This report has been prepared specifically for AngloGold Ashanti Australia. Neither the report nor its contents may be referred to or quoted in any statement, study, report, application, prospectus, loan, or other agreement document, without the express approval of ecologia Environment and/or AngloGold Ashanti Australia. ecologia Environment 1025 Wellington St West Perth WA 6005 Ph: 08 9322 1944 Fax: 08 9322 1599 Email: [email protected] i Tropicana Gold Project Tropicana-Transline Infrastructure Corridor Flora and Vegetation Survey Executive Summary The Tropicana JV (TJV) is currently undertaking pre-feasibility studies on the viability of establishing the Tropicana Gold Project (TGP), which is centred on the Tropicana and Havana gold prospects. The proposed TGP is located approximately 330 km east north-east of Kalgoorlie, and 15 km west of the Plumridge Lakes Nature Reserve, on the western edge of the Great Victoria Desert (GVD) biogeographic region of Western Australia. -

Level 1 Fauna Survey of the Gruyere Gold Project Borefields (Harewood 2016)

GOLD ROAD RESOURCES LIMITED GRUYERE PROJECT EPA REFERRAL SUPPORTING DOCUMENT APPENDIX 5: LEVEL 1 FAUNA SURVEY OF THE GRUYERE GOLD PROJECT BOREFIELDS (HAREWOOD 2016) Gruyere EPA Ref Support Doc Final Rev 1.docx Fauna Assessment (Level 1) Gruyere Borefield Project Gold Road Resources Limited January 2016 Version 3 On behalf of: Gold Road Resources Limited C/- Botanica Consulting PO Box 2027 BOULDER WA 6432 T: 08 9093 0024 F: 08 9093 1381 Prepared by: Greg Harewood Zoologist PO Box 755 BUNBURY WA 6231 M: 0402 141 197 T/F: (08) 9725 0982 E: [email protected] GRUYERE BOREFIELD PROJECT –– GOLD ROAD RESOURCES LTD – FAUNA ASSESSMENT (L1) – JAN 2016 – V3 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1 2. SCOPE OF WORKS ...............................................................................................1 3. RELEVANT LEGISTALATION ................................................................................2 4. METHODS...............................................................................................................3 4.1 POTENTIAL VETEBRATE FAUNA INVENTORY - DESKTOP SURVEY ............. 3 4.1.1 Database Searches.......................................................................................3 4.1.2 Previous Fauna Surveys in the Area ............................................................3 4.1.3 Existing Publications .....................................................................................5 4.1.4 Fauna -

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.PDF

Version: 1.7.2015 South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 An Act to provide for the establishment and management of reserves for public benefit and enjoyment; to provide for the conservation of wildlife in a natural environment; and for other purposes. Contents Part 1—Preliminary 1 Short title 5 Interpretation Part 2—Administration Division 1—General administrative powers 6 Constitution of Minister as a corporation sole 9 Power of acquisition 10 Research and investigations 11 Wildlife Conservation Fund 12 Delegation 13 Information to be included in annual report 14 Minister not to administer this Act Division 2—The Parks and Wilderness Council 15 Establishment and membership of Council 16 Terms and conditions of membership 17 Remuneration 18 Vacancies or defects in appointment of members 19 Direction and control of Minister 19A Proceedings of Council 19B Conflict of interest under Public Sector (Honesty and Accountability) Act 19C Functions of Council 19D Annual report Division 3—Appointment and powers of wardens 20 Appointment of wardens 21 Assistance to warden 22 Powers of wardens 23 Forfeiture 24 Hindering of wardens etc 24A Offences by wardens etc 25 Power of arrest 26 False representation [3.7.2015] This version is not published under the Legislation Revision and Publication Act 2002 1 National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972—1.7.2015 Contents Part 3—Reserves and sanctuaries Division 1—National parks 27 Constitution of national parks by statute 28 Constitution of national parks by proclamation 28A Certain co-managed national -

Draft Animal Keepers Species List

Revised NSW Native Animal Keepers’ Species List Draft © 2017 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. All content in this publication is owned by OEH and is protected by Crown Copyright, unless credited otherwise. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons. OEH asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2017. Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59 Goulburn Street, Sydney NSW 2000 PO Box A290, -

An Annotated Type Catalogue of the Dragon Lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in the Collection of the Western Australian Museum Ryan J

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 34 115–132 (2019) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.34(2).2019.115-132 An annotated type catalogue of the dragon lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in the collection of the Western Australian Museum Ryan J. Ellis Department of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. Biologic Environmental Survey, 24–26 Wickham St, East Perth, Western Australia 6004, Australia. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The Western Australian Museum holds a vast collection of specimens representing a large portion of the 106 currently recognised taxa of dragon lizards (family Agamidae) known to occur across Australia. While the museum’s collection is dominated by Western Australian species, it also contains a selection of specimens from localities in other Australian states and a small selection from outside of Australia. Currently the museum’s collection contains 18,914 agamid specimens representing 89 of the 106 currently recognised taxa from across Australia and 27 from outside of Australia. This includes 824 type specimens representing 45 currently recognised taxa and three synonymised taxa, comprising 43 holotypes, three syntypes and 779 paratypes. Of the paratypes, a total of 43 specimens have been gifted to other collections, disposed or could not be located and are considered lost. An annotated catalogue is provided for all agamid type material currently and previously maintained in the herpetological collection of the Western Australian Museum. KEYWORDS: type specimens, holotype, syntype, paratype, dragon lizard, nomenclature. INTRODUCTION Australia was named by John Edward Gray in 1825, The Agamidae, commonly referred to as dragon Clamydosaurus kingii Gray, 1825 [now Chlamydosaurus lizards, comprises over 480 taxa worldwide, occurring kingii (Gray, 1825)]. -

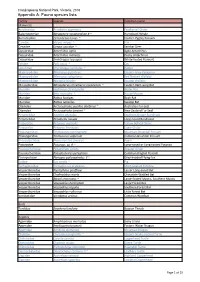

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus -

By H.D.V. PRENDERGAST a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. January 1

STRUCTURAL, BIOCHEMICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL RELATIONSHIPS IN AUSTRALIAN c4 GRASSES (POACEAE) • by H.D.V. PRENDERGAST A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. January 1987. Canberra, Australia. i STATEMENT This thesis describes my own work which included collaboration with Dr N .. E. Stone (Taxonomy Unit, R .. S .. B.S .. ), whose expertise in enzyme assays enabled me to obtain comparative information on enzyme activities reported in Chapters 3, 5 and 7; and with Mr M.. Lazarides (Australian National Herbarium, c .. s .. r .. R .. O .. ), whose as yet unpublished taxonomic views on Eragrostis form the basis of some of the discussion in Chapter 3. ii This thesis describes the results of research work carried out in the Taxonomy Unit, Research School of Biological Sciences, The Australian National University during the tenure of an A.N.U. Postgraduate Scholarship. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My time in the Taxonomy Unit has been a happy one: I could not have asked for better supervision for my project or for a more congenial atmosphere in which to work. To Dr. Paul Hattersley, for his help, advice, encouragement and friendship, I owe a lot more than can be said in just a few words: but, Paul, thanks very much! To Mr. Les Watson I owe as much for his own support and guidance, and for many discussions on things often psittacaceous as well as graminaceous! Dr. Nancy Stone was a kind teacher in many days of enzyme assays and Chris Frylink a great help and friend both in and out of the lab •• Further thanks go to Mike Lazarides (Australian National Herbarium, c.s.I.R.O.) for identifying many grass specimens and for unpublished data on infrageneric groups in Eragrostis; Dr. -

Flora Survey on Hiltaba Station and Gawler Ranges National Park

Flora Survey on Hiltaba Station and Gawler Ranges National Park Hiltaba Pastoral Lease and Gawler Ranges National Park, South Australia Survey conducted: 12 to 22 Nov 2012 Report submitted: 22 May 2013 P.J. Lang, J. Kellermann, G.H. Bell & H.B. Cross with contributions from C.J. Brodie, H.P. Vonow & M. Waycott SA Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Vascular plants, macrofungi, lichens, and bryophytes Bush Blitz – Flora Survey on Hiltaba Station and Gawler Ranges NP, November 2012 Report submitted to Bush Blitz, Australian Biological Resources Study: 22 May 2013. Published online on http://data.environment.sa.gov.au/: 25 Nov. 2016. ISBN 978-1-922027-49-8 (pdf) © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resouces, South Australia, 2013. With the exception of the Piping Shrike emblem, images, and other material or devices protected by a trademark and subject to review by the Government of South Australia at all times, this report is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. All other rights are reserved. This report should be cited as: Lang, P.J.1, Kellermann, J.1, 2, Bell, G.H.1 & Cross, H.B.1, 2, 3 (2013). Flora survey on Hiltaba Station and Gawler Ranges National Park: vascular plants, macrofungi, lichens, and bryophytes. Report for Bush Blitz, Australian Biological Resources Study, Canberra. (Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia: Adelaide). Authors’ addresses: 1State Herbarium of South Australia, Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (DEWNR), GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia. -

A Framework for Mapping Vegetation Over Broad Spatial Extents: a Technique to Aid Land Management Across Jurisdictional Boundaries

Landscape and Urban Planning 97 (2010) 296–305 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Landscape and Urban Planning journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landurbplan A framework for mapping vegetation over broad spatial extents: A technique to aid land management across jurisdictional boundaries Angie Haslem a,b,∗, Kate E. Callister a, Sarah C. Avitabile a, Peter A. Griffioen c, Luke T. Kelly b, Dale G. Nimmo b, Lisa M. Spence-Bailey a, Rick S. Taylor a, Simon J. Watson b, Lauren Brown a, Andrew F. Bennett b, Michael F. Clarke a a Department of Zoology, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3086, Australia b School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Deakin University, Burwood, Victoria 3125, Australia c Peter Griffioen Consulting, Ivanhoe, Victoria 3079, Australia article info abstract Article history: Mismatches in boundaries between natural ecosystems and land governance units often complicate an Received 2 October 2009 ecosystem approach to management and conservation. For example, information used to guide man- Received in revised form 25 June 2010 agement, such as vegetation maps, may not be available or consistent across entire ecosystems. This Accepted 5 July 2010 study was undertaken within a single biogeographic region (the Murray Mallee) spanning three Aus- Available online 7 August 2010 tralian states. Existing vegetation maps could not be used as vegetation classifications differed between states. Our aim was to describe and map ‘tree mallee’ vegetation consistently across a 104 000 km2 area Keywords: of this region. Hierarchical cluster analyses, incorporating floristic data from 713 sites, were employed Semi-arid ecosystems Mallee vegetation to identify distinct vegetation types. Neural network classification models were used to map these veg- Remote sensing etation types across the region, with additional data from 634 validation sites providing a measure of Neural network classification models map accuracy.