Chuck Klosterman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

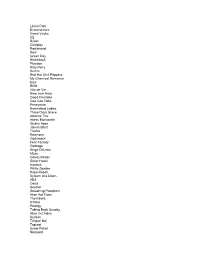

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay Radiohead Korn Green Day Nickelback Placebo Katy Perry Kumm Red Hot Chili Peppers My Chemical Romance Eels REM Vita de Vie Nine Inch Nails Good Charlotte Goo Goo Dolls Pennywise Barenaked Ladies Three Days Grace Alkaline Trio Alanis Morissette Guano Apes James Blunt Travka Reamonn Godsmack Fear Factory Garbage Kings Of Leon Muse Gandul Matei Sister Hazel Incubus White Zombie Papa Roach System of a Down AB4 Oasis Seether Smashing Pumpkins Alien Ant Farm The Killers Ill Nino Prodigy Taking Back Sunday Alice in Chains Kutless Timpuri Noi Taproot Snow Patrol Nonpoint Dashboard Confessional The Cure The Cranberries Stereophonics Blink 182 Phish Blur Rage Against the Machine Gorillaz Pulp Bowling For Soup Citizen Cope Manic Street Preachers Luna Amara Nirvana The Verve Breaking Benjamin Chevelle Modest Mouse Jeff Buckley Beck Arctic Monkeys Bloodhound Gang Sevendust Coma Lostprophets Keane Blue October 30 Seconds to Mars Suede Collective Soul Kill Hannah Foo Fighters The Cult Feeder Veruca Salt Skunk Anansie 3 Doors Down Deftones Sugar Ray Counting Crows Mushroomhead Electric Six Filter Lynyrd Skynyrd Biffy Clyro Death Cab For Cutie Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds The White Stripes James Morrison Texas Crazy Town Mudvayne Placebo Crash Test Dummies Poets Of The Fall Jason Mraz Linkin Park Sum 41 Grimus Guster A Perfect Circle Tool The Strokes Flyleaf Chris Cornell Smile Empty Soul Audioslave Nirvana Gogol Bordello Bloc Party Thousand Foot Krutch Brand New Razorlight Puddle Of Mudd Sonic Youth -

Irish Scene and Sound

IRISH SCENE AND SOUND IRISH SCENE AND SOUND Identity, Authenticity and Transnationality among Young Musicians Virva Basegmez Stockholm Studies in Social Anthropology, 57 2005 IRISH SCENE AND SOUND Identity, Authenticity and Transnationality among Young Musicians Doctoral dissertation © Virva Basegmez 2005 Stockholm Studies in Social Anthropology, 57 Cover design by Helen Åsman and Virva Basegmez Cover photo by Virva Basegmez Department of Social Anthropology Stockholm University S-106 91 Stockholm Sweden All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author. ISBN 91-7155-084-4 Printed by Elanders Gotab, Stockholm 2005 This book is distributed by Almqvist & Wiksell International P.O. Box 76 34 S-103 94 Stockholm Sweden E-mail: [email protected] To Tilda and Murat CONTENTS Acknowledgements x 1 INTRODUCTION: SCENES IN THE SCENE 1 Irish national identity: past and present dislocation 5 Anthropology of Ireland, rural and urban 14 Fields in the field 16 Media contexts, return visits and extended ethnography 20 The Celtic Tiger and the Irish international music industry 22 Outline of the chapters 28 2 GENRE, SOUND AND PATHWAYS 31 Studies of popular music and some theoretical orientations 31 The concept of genre: flux, usage, context 34 Genre, style and canonisation 37 Music genres in Ireland 39 Irish traditional music and its revival 39 Irish rock music and indies 44 Showbands, cover bands and tribute bands 45 Folk rock and Celtic music 47 Fusions, world music, -

City of Orillia a G E N

CITY OF ORILLIA Regular Council Meeting Monday, November 28, 2011 - 7:30 p.m. Council Chamber, Orillia City Centre A G E N D A Infrared hearing aids are available in the Council Chamber courtesy of the Orillia Quota Club. They are located on the east wall at the back of the Chamber. Page Call to Order O Canada Moment of Silence Approval of Agenda Disclosure of Interest Presentation Deputations 7-41 1. Katelyn Murphy, Steven Howcroft and Janice Charnock, students from Georgian College, will be present to discuss a community funding project that would address specific issues of hunger and homelessness in Orillia. File: A01-GEN 43-47 2. Sarah-Jane Valiquette will be present to discuss a proposal for a Bleeker Ridge Block Party in support of the Orillia Youth Centre. File: M02-GEN Minutes - November 14, 2011 Correspondence Enquiries Reports 49-50 1. Report Number 2011-39 of Council Committee. Notice of Motion 51-54 1. Councillor Spears hereby gives notice that he intends to introduce the following motion: Page 1 of 170 Page Notice of Motion "THAT the letter dated August 24, 2011 from Ken McMullen on behalf of Second Mariposa Non Profit Housing Corporation, regarding an acre of land from the City and referring to funding requested in a previous letter, be directed to the Housing Committee for discussion and a report to Council." a) Report - Councillor Spears. Motions 55-87 1. At the November 14, 2011 Council meeting, the following motion was Tabled: "THAT, further to the deputation by the Mariposa Folk Festival requesting permission for on-site camping for ticket holders, the organizers be given approval subject to their compliance with the facility permitting process." a) Letter dated October 24, 2011 from the Mariposa Folk Festival. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title (Aerosmith) 02)Nwa 10 Years I Dont Wanna Miss A Thing Real Niggas Don't Die Through The Iris (Busta Rhymes Feat Mariah 03 Waking Up Carey) If You Want Me To Stay Wasteland I Know What You Want (Remix) 100% Funk (Ricky Martin) 04 Play That Funky Music White Living La Vida Loca Behind The Sun (Ben Boy (Rose) Love Songs Grosse Mix) 101bpm Ciara F. Petey Eric Clapton - You Look 04 Johnny Cash Pablo Wonderful Tonight In The Jailhouse Goodies Lethal Weapon (Soplame.Com ) 05 11 The Platters - Only You Castles Made Of Sand (Live) Police Helicopter (Demo) (Vitamin C) 05 Johnny Cash 11 Johnny Cash Graduation (Friends Forever) Ring Of Fire Sunday Morning C .38 Special 06 112 Featuring Foxy Brown Caught Up In You Special Secret Song Inside U Already Know [Huey Lewis & The News] 06 Johnny Cash 112 Ft. Beanie Sigel I Want A New Drug (12 Inch) Understand Your Dance With Me (Remix) [Pink Floyd] 07 12 Comfortably Numb F.U. (Live) Nevermind (Demo) +44 07 Johnny Cash 12 Johnny Cash Baby Come On The Ballad Of Ir Flesh And Blood 01 08 12 Stones Higher Ground (12 Inch Mix) Get Up And Jump (Demo) Broken-Ksi Salt Shaker Feat. Lil Jon & Godsmack - Going Down Crash-Ksi Th 08 Johnny Cash Far Away-Ksi 01 Johnny Cash Folsom Prison Bl Lie To Me I Still Miss Som 09 Photograph-Ksi 01 Muddy Waters Out In L.A. (Demo) Stay-Ksi I Got My Brand On You ¼‚½‚©Žq The Way I Feel-Ksi 02 Another Birthday 13 Hollywood (Africa) (Dance ¼¼ºñÁö°¡µç(Savage Let It Shine Mix) Garden) Sex Rap (Demo) 02 Johnny Cash I Knew I Loved You 13 Johnny Cash The Legend -

Motion City Soundtrack Tour Dates – 2005 Motion City Memories

Motion City Soundtrack Tour Dates – 2005 Motion City Memories - http://www.motioncitysoundtrack.net JANUARY FEBRUARY 2/02/05: Cincinnati, OH - Bogart’s - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/03/05: DeKalb, IL - Duke Ellington Ballroom - w/ The Matches, From First To Last, Matchbook Romance 2/04/05: St. Louis, MO - Mississippi Nights - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/05/05: Lawrence, KS - The Bottleneck - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/06/05: Denver, CO - Ogden Theatre - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/08/05: Salt Lake City, UT - Lo-Fi Cafe - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/09/05: Boise, ID - The Big Easy - w/ The Matches, From First To Last, Matchbook Romance 2/10/05: Seattle, WA - El Corazón - w/ The Matches, From First To Last, Matchbook Romance 2/11/05: Portland, OR - Meow Meow - w/ The Matches, From First To Last, Matchbook Romance 2/12/05: Orangevale, CA - The Boardwalk - w/ The Matches, From First To Last, Matchbook Romance 2/13/05: San Francisco, CA - Slim's - w/ From First To Last, Matchbook Romance 2/15/05: Bakersfield, CA - The Dome - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/16/05: Anaheim, CA - House Of Blues - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/17/05: West Hollywood, CA - House Of Blues - w/ The Matches, From First To Last, Matchbook Romance 2/18/05: San Diego, CA - Soma - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/19/05: Tempe, AZ - Marquee Theatre - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/21/05: Dallas, TX - Trees - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/22/05: San Antonio, TX - White Rabbit - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/23/05: Houston, TX - Meridian - w/ Matchbook Romance 2/25/05: Tallahassee, FL - Club Downunder (Florida State University) - w/ Matchbook -

Dictionary of Media and Communications

Dictionary of Media and Communications Dictionary of Media and Communications Marcel Danesi M.E.Sharpe Armonk, New York London, England FOREWORD Copyright © 2009 by M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 80 Business Park Drive, Armonk, New York 10504. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Danesi, Marcel, 1946– Dictionary of media and communications / Marcel Danesi; foreword by Arthur Asa Berger. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-7656-8098-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Mass media—Dictionaries. 2. Communication—Dictionaries. I. Title. P87.5.D359 2008 302.2303—dc22 2008011560 Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.48-1984. ~ BM (c) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ——— ————————————————— Images provided by Getty Images and the following: AFP: page 235; Andreas Solaro/Stringer/AFP: 82; Aubrey Beardsley/The Bridgeman Art Library: 27; Bernard Gotfryd/Hulton Archive: 190; Blank Archives/Hulton Archive: 16; Buyenlarge/Time & Life Pictures: 5, 155; CBS Photo Archive/Hulton Archive: 256; Dave Bradley Photography/Taxi: 127; Deshakalyan Chowdhury/Stringer/AFP: 60; Disney/Hulton Archive: 118; Ethan Miller: 43; Evan Agostini: 55; George Pierre Seurat/The Bridge- man Art Library: 234; Hulton Archive/Stringer: 36, 92, 129; Italian School/The Bridgeman Art Library: 153; Mario Tama: 67; Michael Ochs Archive/Stringer: 147; Paul Nicklen/National Geographic: 223; RDA/Hulton Archive: 53; Shelly Katz/Time & Life Pictures: 178; Stringer/AFP: 303; Stringer: 137; Susanna Price/Dorling Kindersley: 134; Time & Life Pictures/Stringer: 55, 182, 184; Transcendental Graphics/Hulton Archive: 188; Vince Bucci/Stringer: 221; Walter Sanders/Time & Life Pictures: 219; Yoshikazu Tsuno/AFP: 229.