Magedera, I. H. Tipu Sultan:

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report

Karnataka Tourism Vision group 2014 report KARNATAKA TOURISM VISION GROUP (KTVG) Recommendations to the GoK: Jan 2014 Task force KTVG Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report 1 FOREWORD Tourism matters. As highlighted in the UN WTO 2013 report, Tourism can account for 9% of GDP (direct, indirect and induced), 1 in 11 jobs and 6% of world exports. We are all aware of amazing tourist experiences globally and the impact of the sector on the economy of countries. Karnataka needs to think big, think like a Nation-State if it is to forge ahead to realise its immense tourism potential. The State is blessed with natural and historical advantage, which coupled with a strong arts and culture ethos, can be leveraged to great advantage. If Karnataka can get its Tourism strategy (and brand promise) right and focus on promotion and excellence in providing a wholesome tourist experience, we believe that it can be among the best destinations in the world. The impact on job creation (we estimate 4.3 million over the next decade) and economic gain (Rs. 85,000 crores) is reason enough for us to pay serious attention to focus on the Tourism sector. The Government of Karnataka had set up a Tourism Vision group in Oct 2013 consisting of eminent citizens and domain specialists to advise the government on the way ahead for the Tourism sector. In this exercise, we had active cooperation from the Hon. Minister of Tourism, Mr. R.V. Deshpande; Tourism Secretary, Mr. Arvind Jadhav; Tourism Director, Ms. Satyavathi and their team. The Vision group of over 50 individuals met jointly in over 7 sessions during Oct-Dec 2013. -

PART 1 of Volume 13:6 June 2013

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 13:6 June 2013 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Contents Drama in Indian Writing in English - Tradition and Modernity ... 1-101 Dr. (Mrs.) N. Velmani Reflection of the Struggle for a Just Society in Selected Poems of Niyi Osundare and Mildred Kiconco Barya ... Febisola Olowolayemo Bright, M.A. 102-119 Identity Crisis in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake ... Anita Sharma, M.Phil., NET, Ph.D. Research Scholar 120-125 A Textual Study of Context of Personal Pronouns and Adverbs in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” ... Fadi Butrus K Habash, M.A. 126-146 Crude Oil Price Behavior and Its Impact on Macroeconomic Variable: A Case of Inflation ... M. Anandan, S. Ramaswamy and S. Sridhar 147-161 Using Exact Formant Structure of Persian Vowels as a Cue for Forensic Speaker Recognition ... Mojtaba Namvar Fargi, Shahla Sharifi, Mohammad Reza Pahlavan-Nezhad, Azam Estaji, and Mehi Meshkat Aldini Ferdowsi University of Mashhad 162-181 Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 13:6 June 2013 Contents List i Simplification of CC Sequence of Loan Words in Sylheti Bangla ... Arpita Goswami, Ph.D. Research Scholar 182-191 Impact of Class on Life A Marxist Study of Thomas Hardy’s Novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles .. -

Mysore Tourist Attractions Mysore Is the Second Largest City in the State of Karnataka, India

Mysore Tourist attractions Mysore is the second largest city in the state of Karnataka, India. The name Mysore is an anglicised version of Mahishnjru, which means the abode of Mahisha. Mahisha stands for Mahishasura, a demon from the Hindu mythology. The city is spread across an area of 128.42 km² (50 sq mi) and is situated at the base of the Chamundi Hills. Mysore Palace : is a palace situated in the city. It was the official residence of the former royal family of Mysore, and also housed the durbar (royal offices).The term "Palace of Mysore" specifically refers to one of these palaces, Amba Vilas. Brindavan Gardens is a show garden that has a beautiful botanical park, full of exciting fountains, as well as boat rides beneath the dam. Diwans of Mysore planned and built the gardens in connection with the construction of the dam. Display items include a musical fountain. Various biological research departments are housed here. There is a guest house for tourists.It is situated at Krishna Raja Sagara (KRS) dam. Jaganmohan Palace : was built in the year 1861 by Krishnaraja Wodeyar III in a predominantly Hindu style to serve as an alternate palace for the royal family. This palace housed the royal family when the older Mysore Palace was burnt down by a fire. The palace has three floors and has stained glass shutters and ventilators. It has housed the Sri Jayachamarajendra Art Gallery since the year 1915. The collections exhibited here include paintings from the famed Travancore ruler, Raja Ravi Varma, the Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich and many paintings of the Mysore painting style. -

Mehendale Book-10418

Tipu as He Really Was Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale Tipu as He Really Was Copyright © Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale First Edition : April, 2018 Type Setting and Layout : Mrs. Rohini R. Ambudkar III Preface Tipu is an object of reverence in Pakistan; naturally so, as he lived and died for Islam. A Street in Islamabad (Rawalpindi) is named after him. A missile developed by Pakistan bears his name. Even in India there is no lack of his admirers. Recently the Government of Karnataka decided to celebrate his birth anniversary, a decision which generated considerable opposition. While the official line was that Tipu was a freedom fighter, a liberal, tolerant and enlightened ruler, its opponents accused that he was a bigot, a mass murderer, a rapist. This book is written to show him as he really was. To state it briefly: If Tipu would have been allowed to have his way, most probably, there would have been, besides an East and a West Pakistan, a South Pakistan as well. At the least there would have been a refractory state like the Nizam's. His suppression in 1792, and ultimate destruction in 1799, had therefore a profound impact on the history of India. There is a class of historians who, for a long time, are portraying Tipu as a benevolent ruler. To counter them I can do no better than to follow Dr. R. C. Majumdar: “This … tendency”, he writes, “to make history the vehicle of certain definite political, social and economic ideas, which reign supreme in each country for the time being, is like a cloud, at present no bigger than a man's hand, but which may soon grow in volume, and overcast the sky, covering the light of the world by an impenetrable gloom. -

Tipu Sultan's Mission to the Ottoman Empire

American International Journal of Available online at http://www.iasir.net Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences ISSN (Print): 2328-3734, ISSN (Online): 2328-3696, ISSN (CD-ROM): 2328-3688 AIJRHASS is a refereed, indexed, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary and open access journal published by International Association of Scientific Innovation and Research (IASIR), USA (An Association Unifying the Sciences, Engineering, and Applied Research) Seeking an Ally against British Expansion in India: Tipu Sultan’s Mission to the Ottoman Empire Emre Yuruk Research Scholar, Centre for West Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 110067, INDIA Abstract: After British defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588, they emerged as a new power in Europe and expanded its sovereignty all over the world by controlling overseas trade gradually. They aimed to take advantage of the wealth of India thanks to East India Company starting from 17th century and in time; they established their hegemony in the Indian subcontinent. When Tipu Sultan the ruler of Mysore realised this colonial intention of British over India in the second half of 18th century, he wanted to remove them from India. However, the support that Tipu Sultan needed was not given by Indian local rulers Mughals, Nizam and Marathas. Thus, Tipu Sultan turned his policy to the Ottoman Empire. He sent a mission to Constantinople with some valuable gifts to take Ottoman’s assistance against British. The proposed paper analyses the correspondences of Tipu Sultan and Ottoman Sultans Abdulh amid I and Selim III and how British superior diplomacy dealt with French, the Ottomans and Indian native rulers to suppress Tipu Sultan from accumulating power as well as to stop him from making any alliances to the detriment of British interest. -

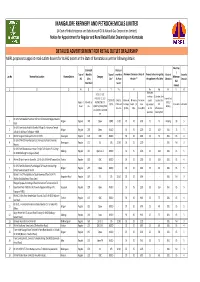

Final for Advertisement.Xlsx

MANGALORE REFINERY AND PETROCHEMICALS LIMITED (A Govt of India Enterprise and Subsidiary of Oil & Natural Gas Corporation Limited) Notice for Appointment for Regular and Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships in Karnataka DETAILED ADVERTISEMENT FOR RETAIL OUTLET DEALERSHIP MRPL proposes to appoint retail outlets dealers for its HiQ outlets in the State of Karnataka as per the following details: Fixed Fee Estimated Rent per / Type of Monthly Type of month in Minimum Dimension /Area of Finance to be arranged by Mode of Security Loc.No Name of the Location Revnue District Category Minimum RO Sales Site* Rs.P per the site ** the applicant in Rs Lakhs Selection Deposit Bid Potential # Sq.mt amount 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 7A 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Estimated SC/SC CC-1/SC working Estimated fund PH/ST/ST CC-1/ST Draw of Lots CODO/DOD Only for Minimum Minimum Minimum capital required for Regular / MS+HSD in PH/OBC/OBC CC- (DOL) / O/CFS CODO and Frontage Depth (in Area requirement RO in Rs Lakhs in Rs Lakhs Rural KLs 1/OBC PH/OPEN/OPEN Bidding CFS sites (in Mts) Mts) (in Sq.Mts) for RO infrastructure CC-1/OPEN CC-2/OPEN operation development PH On LHS From Mezban Function Hall To Indal Circle On Belgavi Bauxite 1 Belgavi Regular 240 Open CODO 51.00 20 20 600 25 15 Bidding 30 5 Road On LHS From Kerala Hotel In Biranholi Village To Hanuman Temple 2 Belgavi Regular 230 Open DODO - 35 35 1225 25 100 DOL 15 5 ,Ukkad On Kolhapur To Belgavi - NH48 3 Within Tanigere Panchayath Limit On SH 76 Davangere Regular 105 OBC DODO - 30 30 900 25 75 DOL 15 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards 4 Ramnagara Regular 171 SC CFS 22.90 35 35 1225 - - DOL Nil 3 Mysore On LHS From Sharanabasaveshwar Temple To St Xaviers P U College 5 Kalburgi Regular 225 Open CC-1 DODO - 35 35 1225 25 100 DOL 15 5 On NH50 (Kalburgi To Vijaypura Road) 6 Within 02 Kms From Km Stone No. -

Heritage of Mysore Division

HERITAGE OF MYSORE DIVISION - Mysore, Mandya, Hassan, Chickmagalur, Kodagu, Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Chamarajanagar Districts. Prepared by: Dr. J.V.Gayathri, Deputy Director, Arcaheology, Museums and Heritage Department, Palace Complex, Mysore 570 001. Phone:0821-2424671. The rule of Kadambas, the Chalukyas, Gangas, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas, Vijayanagar rulers, the Bahamanis of Gulbarga and Bidar, Adilshahis of Bijapur, Mysore Wodeyars, the Keladi rulers, Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan and the rule of British Commissioners have left behind Forts, Magnificient Palaces, Temples, Mosques, Churches and beautiful works of art and architecture in Karnataka. The fauna and flora, the National parks, the animal and bird sanctuaries provide a sight of wild animals like elephants, tigers, bisons, deers, black bucks, peacocks and many species in their natural habitat. A rich variety of flora like: aromatic sandalwood, pipal and banyan trees are abundantly available in the State. The river Cauvery, Tunga, Krishna, Kapila – enrich the soil of the land and contribute to the State’s agricultural prosperity. The water falls created by the rivers are a feast to the eyes of the outlookers. Historical bakground: Karnataka is a land with rich historical past. It has many pre-historic sites and most of them are in the river valleys. The pre-historic culture of Karnataka is quite distinct from the pre- historic culture of North India, which may be compared with that existed in Africa. 1 Parts of Karnataka were subject to the rule of the Nandas, Mauryas and the Shatavahanas; Chandragupta Maurya (either Chandragupta I or Sannati Chandragupta Asoka’s grandson) is believed to have visited Sravanabelagola and spent his last years in this place. -

Architectural Research Writing, 6Th Semester, 2020

International Journal for Research in Engineering Application & Management (IJREAM) ISSN : 2454-9150 Vol-06, Issue-02, May 2020 Old yet majestic A study of Adaptive reuse in the case of Opera House, Bengaluru 1Hitha C, 2M Kalaiarasan, 3Bharath Kumar S, 4Ar. Prerana Hazarika 1,2,3Student, 6th Sem, 4Assistant Professor, School of Architecture, Reva University, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. [email protected] Abstract- Once a garden city bustling with many heritage structures, Bangalore is now a busy software hub with heritage structures pulled down one by one, losing its threads to past. Of the few heritage structures that remain, the concept of “Adaptive reuse” has been nothing short of a revelation. The term adaptive reuse maybe defined as „a process of reusing an existing building for a purpose other than which it was originally built or designed for; but when heritage buildings are to be considered adaptive reuse should be a process of preserving and restoring the building with minimal changes and for a use that does not effect the cultural and historical background of the building.‟ This research explores the effectiveness of adaptive reuse in preserving the heritage value of the buildings in Bangalore, considering the case of Samsung Opera House, a century old structure, located at the main junction of Brigade road. The paper will focus on how this structure has been restored and how the building has been repurposed as a showroom. It will also draw similarities and how other heritage buildings in Bangalore have been reused to meet the needs of the current day using few case studies like Cinnamon Boutique. -

Srirangapatna Travel Guide - Page 1

Srirangapatna Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/srirangapatna page 1 one dare touch it. And, if stones could Feb speak, probably every tiny pebble on the Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Srirangapatna banks of the Cauvery would make the Max: Min: Rain: 0.0mm 25.70000076 11.39999961 2939453°C 8530273°C Located strategically at a mere 15 English go red with reminiscences of Tipu’s conquest over the ‘Unconquerable Empire’. km drive by road from the Palace Mar The lanes between the turfed outline of the City of Mysore, a trip to Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Srirangapatna Fort bear touching memorials Max: 18.0°C Min: Rain: 0.0mm Srirangapatna makes its visitor 14.39999961 to the life of this unique king. 8530273°C relive the days of valor and Apr gallantry. The relics of Famous For : City But if you’re not too keen on going Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Srirangapatna with its temples, ‘histerical’ on a weekend and need other Max: Min: Rain: 6.0mm palaces, tombs, military Srirangapatna, an egg shaped island diversions, Srirangapatna won’t let you 25.10000038 12.30000019 1469727°C 0734863°C warehouses, cenotaphs, splendid enclosed by the river Kaveri and the historic down. The drive itself, past the golden rocks landscape and above all its three capital of Tipu Sultan, is sprinkled all across on which Sholay was shot 35 years ago and May with temples symbolic of the British rule. through the paddy fields of Mandya, is Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, layer fort wall with bastions are a umbrella. -

R E D Is C O V E R in G T Ip U

Susan Stronge REDISCOVERING TIPU SULTAN’S TREASURY TREASURY Few stories in the annals of British involvement in India are as dramatic as their storming of the citadel of the mier of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, in 1799. The legacy of the event as preserved in the arts of British India, and even more so in those of Britain itself, is very marked. Western artists in India produced paintings and drawings of the key sites in the campaign, the monuments and fortifications of the region, and portraits of its leading characters, reproductions of which were disseminated widely in Britain as engravings.1 At home, artists used their imagination to depict the discovery of the body of Tipu Sultan in the immediate aftermath of the siege, and the siege itself was SULTAN'S re-enacted in London as an entertainment by Astley’s, the precursor of the modern circus.2 A huge panorama of the Siege of Seringapatam was created by the young Scottish artist Robert Ker Porter in 1800, its details taken Trom the most authentic and correct Information relative to the Scenery of the Place, the Costume of the Soldiery, and the various Circumstances of the TIPU Attack.’ It was exhibited in London to enthusiastic crowds.3 Yet these events, which produced such a range of artistic responses from the side of the victors, were responsible for the almost complete obliteration of evidence of the ruler’s own much more varied artistic patronage during his brief reign, which had begun in 1782. Over the last decades, scholars have systematically tracked down material dispersed from the royal treasury at Tipu Sultan’s Capital known to him as Srirangapatan, or simply ‘Patan’, and to the British as Seringapatam, but discoveries are still to be made.4 One such is a pair of finials in the Victoria and Albert Museum made of heavily cast silver, thickly gilded and with chased decoration (fig. -

Deconstructing Tipu Sultan's Tiger Symbol in G.A. Henty's Novel The

Deconstructing Tipu Sultan’s Tiger Symbol in G.A. Henty’s Novel The Tiger of Mysore Ayesha Rafiq* ABSTRACT: This paper deconstructs G.A. Henty’s novel The Tiger of Mysore to show that it subverts Tipu Sultan’s tiger emblem to undermine his courage, martial ingenuity, and spirit of independence. Using Derrida’s concept of différance the study undertakes a close reading of tiger imagery to reveal that emblematic of Tipu’s leadership the Indian tiger is variously portrayed as formidable to morbidly bloodthirsty and finally as vulnerable. This method demonstrates that Tipu’s shifting interpretations conveyed through the tiger motif are influenced by the expediency of the period and circumstances prevailing then. The variations in Tipu’s portrayal come down to one conclusion, i.e. to vilify Tipu and to justify expansion of the British Empire. Keywords: tiger emblem; Tipu's leadership; subversion; variations; British Empire * Email: [email protected] Journal of Research in Humanities 110 Introduction “…the hide of Shere Khan is under my feet. All the jungle knows that I have killed Shere Khan” (91-94). From The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling The tiger, symbolizing fiercely independent spirit of India1, lays subdued underneath Mowgli, representing celebration of British superiority. The tiger motif, which mainly takes the form of a menacing tiger- a man eater and a perpetual scourge to the locals, persistently appears in colonial British writings on India particularly the figure of Tipu Sultan. An ardent use of tiger imagery not only underpins British fascination with the Indian space but also accomplishes their twin purpose, i.e. -

Golden Triangle with Tiger Safari

Wonder of South - West India DAY 00 / 10 NOV 2019 / SUNDAY: ARRIVE MUMBAI ( Check in 1200 Hrs) On arrival at Mumbai International airport, meet and greet by our representative. Later, assistance and transfer to hotel. Mumbai (Bombay) is the vibrant and pulsating capital of Maharashtra. For over a century, Mumbai has been a commercial and industrial centre of India with a magnificent harbour, imposing multi-storied buildings, crowded thoroughfares, busy markets, shopping centers and beautiful tourist spots. The British acquired Mumbai from the Portuguese in 1665 and handed it over to the East India Company in 1671 for a handsome annual rent of Sterling Pounds 10 in gold! Later, these seven islands were joined together by causeways and bridges in 1862. Overnight at Mumbai DAY 01 / 11 NOV 2019 / MONDAY: MUMBAI (Bollywood and City Tour) After breakfast we proceed for half day Bollywood tour. Meet your guide to the Bollywood film studio. En route, your guide will inform you about what to expect on your Bollywood tour at Film City, also called Dadasaheb Phalke Nagar in honor of the father of India’s film industry. When you arrive at the Film City complex, head to one of the Bollywood studios for a brief introduction about the origin and evolution of India’s film industry, which has produced more than 67,000 films in at least 30 languages! Learn about the silent film era and the ‘talkies’ – first introduced to India in the early 1930s – as well as the increasing popularity of Bollywood cinema, which incorporates Hindi storytelling through dance, music and song.