Deconstructing Tipu Sultan's Tiger Symbol in G.A. Henty's Novel The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report

Karnataka Tourism Vision group 2014 report KARNATAKA TOURISM VISION GROUP (KTVG) Recommendations to the GoK: Jan 2014 Task force KTVG Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report 1 FOREWORD Tourism matters. As highlighted in the UN WTO 2013 report, Tourism can account for 9% of GDP (direct, indirect and induced), 1 in 11 jobs and 6% of world exports. We are all aware of amazing tourist experiences globally and the impact of the sector on the economy of countries. Karnataka needs to think big, think like a Nation-State if it is to forge ahead to realise its immense tourism potential. The State is blessed with natural and historical advantage, which coupled with a strong arts and culture ethos, can be leveraged to great advantage. If Karnataka can get its Tourism strategy (and brand promise) right and focus on promotion and excellence in providing a wholesome tourist experience, we believe that it can be among the best destinations in the world. The impact on job creation (we estimate 4.3 million over the next decade) and economic gain (Rs. 85,000 crores) is reason enough for us to pay serious attention to focus on the Tourism sector. The Government of Karnataka had set up a Tourism Vision group in Oct 2013 consisting of eminent citizens and domain specialists to advise the government on the way ahead for the Tourism sector. In this exercise, we had active cooperation from the Hon. Minister of Tourism, Mr. R.V. Deshpande; Tourism Secretary, Mr. Arvind Jadhav; Tourism Director, Ms. Satyavathi and their team. The Vision group of over 50 individuals met jointly in over 7 sessions during Oct-Dec 2013. -

PART 1 of Volume 13:6 June 2013

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 13:6 June 2013 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Contents Drama in Indian Writing in English - Tradition and Modernity ... 1-101 Dr. (Mrs.) N. Velmani Reflection of the Struggle for a Just Society in Selected Poems of Niyi Osundare and Mildred Kiconco Barya ... Febisola Olowolayemo Bright, M.A. 102-119 Identity Crisis in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake ... Anita Sharma, M.Phil., NET, Ph.D. Research Scholar 120-125 A Textual Study of Context of Personal Pronouns and Adverbs in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” ... Fadi Butrus K Habash, M.A. 126-146 Crude Oil Price Behavior and Its Impact on Macroeconomic Variable: A Case of Inflation ... M. Anandan, S. Ramaswamy and S. Sridhar 147-161 Using Exact Formant Structure of Persian Vowels as a Cue for Forensic Speaker Recognition ... Mojtaba Namvar Fargi, Shahla Sharifi, Mohammad Reza Pahlavan-Nezhad, Azam Estaji, and Mehi Meshkat Aldini Ferdowsi University of Mashhad 162-181 Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 13:6 June 2013 Contents List i Simplification of CC Sequence of Loan Words in Sylheti Bangla ... Arpita Goswami, Ph.D. Research Scholar 182-191 Impact of Class on Life A Marxist Study of Thomas Hardy’s Novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles .. -

Mysore Tourist Attractions Mysore Is the Second Largest City in the State of Karnataka, India

Mysore Tourist attractions Mysore is the second largest city in the state of Karnataka, India. The name Mysore is an anglicised version of Mahishnjru, which means the abode of Mahisha. Mahisha stands for Mahishasura, a demon from the Hindu mythology. The city is spread across an area of 128.42 km² (50 sq mi) and is situated at the base of the Chamundi Hills. Mysore Palace : is a palace situated in the city. It was the official residence of the former royal family of Mysore, and also housed the durbar (royal offices).The term "Palace of Mysore" specifically refers to one of these palaces, Amba Vilas. Brindavan Gardens is a show garden that has a beautiful botanical park, full of exciting fountains, as well as boat rides beneath the dam. Diwans of Mysore planned and built the gardens in connection with the construction of the dam. Display items include a musical fountain. Various biological research departments are housed here. There is a guest house for tourists.It is situated at Krishna Raja Sagara (KRS) dam. Jaganmohan Palace : was built in the year 1861 by Krishnaraja Wodeyar III in a predominantly Hindu style to serve as an alternate palace for the royal family. This palace housed the royal family when the older Mysore Palace was burnt down by a fire. The palace has three floors and has stained glass shutters and ventilators. It has housed the Sri Jayachamarajendra Art Gallery since the year 1915. The collections exhibited here include paintings from the famed Travancore ruler, Raja Ravi Varma, the Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich and many paintings of the Mysore painting style. -

Anglo-Mysore War

www.gradeup.co Read Important Medieval History Notes based on Mysore from Hyder Ali to Tipu Sultan. We have published various articles on General Awareness for Defence Exams. Important Medieval History Notes: Anglo-Mysore War Hyder Ali • The state of Mysore rose to prominence in the politics of South India under the leadership of Hyder Ali. • In 1761 he became the de facto ruler of Mysore. • The war of successions in Karnataka and Haiderabad, the conflict of the English and the French in the South and the defeat of the Marathas in the Third battle of Panipat (1761) helped him in attending and consolidating the territory of Mysore. • Hyder Ali was defeated by Maratha Peshwa Madhav Rao in 1764 and forced to sign a treaty in 1765. • He surrendered him a part of his territory and also agreed to pay rupees twenty-eight lakhs per annum. • The Nizam of Haiderabad did not act alone but preferred to act in league with the English which resulted in the first Anglo-Mysore War. Tipu Sultan • Tipu Sultan succeeded Hyder Ali in 1785 and fought against British in III and IV Mysore wars. • He brought great changes in the administrative system. • He introduced modern industries by bringing foreign experts and extending state support to many industries. • He sent his ambassadors to many countries for establishing foreign trade links. He introduced new system of coinage, new scales of weight and new calendar. • Tipu Sultan organized the infantry on the European lines and tried to build the modern navy. • Planted a ‘tree of liberty’ at Srirangapatnam and -

Anglo-Mysore Wars

ANGLO-MYSORE WARS The Anglo-Mysore Wars were a series of four wars between the British and the Kingdom of Mysore in the latter half of the 18th century in Southern India. Hyder Ali (1721 – 1782) • Started his career as a soldier in the Mysore Army. • Soon rose to prominence in the army owing to his military skills. • He was made the Dalavayi (commander-in-chief), and later the Chief Minister of the Mysore state under KrishnarajaWodeyar II, ruler of Mysore. • Through his administrative prowess and military skills, he became the de- facto ruler of Mysore with the real king reduced to a titular head only. • He set up a modern army and trained them along European lines. First Anglo-Mysore War (1767 – 1769) Causes of the war: • Hyder Ali built a strong army and annexed many regions in the South including Bidnur, Canara, Sera, Malabar and Sunda. • He also took French support in training his army. • This alarmed the British. Course of the war: • The British, along with the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad declared war on Mysore. • Hyder Ali was able to bring the Marathas and the Nizam to his side with skillful diplomacy. • But the British under General Smith defeated Ali in 1767. • His son Tipu Sultan advanced towards Madras against the English. Result of the war: • In 1769, the Treaty of Madras was signed which brought an end to the war. • The conquered territories were restored to each other. • It was also agreed upon that they would help each other in case of a foreign attack. -

Mehendale Book-10418

Tipu as He Really Was Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale Tipu as He Really Was Copyright © Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale First Edition : April, 2018 Type Setting and Layout : Mrs. Rohini R. Ambudkar III Preface Tipu is an object of reverence in Pakistan; naturally so, as he lived and died for Islam. A Street in Islamabad (Rawalpindi) is named after him. A missile developed by Pakistan bears his name. Even in India there is no lack of his admirers. Recently the Government of Karnataka decided to celebrate his birth anniversary, a decision which generated considerable opposition. While the official line was that Tipu was a freedom fighter, a liberal, tolerant and enlightened ruler, its opponents accused that he was a bigot, a mass murderer, a rapist. This book is written to show him as he really was. To state it briefly: If Tipu would have been allowed to have his way, most probably, there would have been, besides an East and a West Pakistan, a South Pakistan as well. At the least there would have been a refractory state like the Nizam's. His suppression in 1792, and ultimate destruction in 1799, had therefore a profound impact on the history of India. There is a class of historians who, for a long time, are portraying Tipu as a benevolent ruler. To counter them I can do no better than to follow Dr. R. C. Majumdar: “This … tendency”, he writes, “to make history the vehicle of certain definite political, social and economic ideas, which reign supreme in each country for the time being, is like a cloud, at present no bigger than a man's hand, but which may soon grow in volume, and overcast the sky, covering the light of the world by an impenetrable gloom. -

Tipu Sultan's Mission to the Ottoman Empire

American International Journal of Available online at http://www.iasir.net Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences ISSN (Print): 2328-3734, ISSN (Online): 2328-3696, ISSN (CD-ROM): 2328-3688 AIJRHASS is a refereed, indexed, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary and open access journal published by International Association of Scientific Innovation and Research (IASIR), USA (An Association Unifying the Sciences, Engineering, and Applied Research) Seeking an Ally against British Expansion in India: Tipu Sultan’s Mission to the Ottoman Empire Emre Yuruk Research Scholar, Centre for West Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 110067, INDIA Abstract: After British defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588, they emerged as a new power in Europe and expanded its sovereignty all over the world by controlling overseas trade gradually. They aimed to take advantage of the wealth of India thanks to East India Company starting from 17th century and in time; they established their hegemony in the Indian subcontinent. When Tipu Sultan the ruler of Mysore realised this colonial intention of British over India in the second half of 18th century, he wanted to remove them from India. However, the support that Tipu Sultan needed was not given by Indian local rulers Mughals, Nizam and Marathas. Thus, Tipu Sultan turned his policy to the Ottoman Empire. He sent a mission to Constantinople with some valuable gifts to take Ottoman’s assistance against British. The proposed paper analyses the correspondences of Tipu Sultan and Ottoman Sultans Abdulh amid I and Selim III and how British superior diplomacy dealt with French, the Ottomans and Indian native rulers to suppress Tipu Sultan from accumulating power as well as to stop him from making any alliances to the detriment of British interest. -

A Liber Amicorum: Thomas Wälde

A Liber Amicorum: Thomas Wälde Law Beyond Conventional Thought "A Liber Amicorum: Thomas Wälde - Law Beyond Conventional Thought" Edited by Jacques Werner & Arif Hyder Ali Republished on OGEL and TDM with kind permission from CMP Publishing Ltd. Also available as download via http://www.ogel.org/liber-amicorum.asp or http://www.transnational-dispute-management.com/liber-amicorum.asp For more information about the catalogue of books and journals of CMP Publishing visit www.cmppublishing.com Thomas Wälde (1949–2008) A Liber Amicorum: Thomas Wälde Law Beyond Conventional Thought Edited by Jacques Werner & Arif Hyder Ali CAMERON MAY I N T E R N A T I O N A L L A W & P O L I C Y Copyright © CMP Publishing Cameron May is an imprint of CMP Publishing Ltd Published 2009 by CMP Publishing Ltd 13 Keepier Wharf, 12 Narrow Street, London E14 8DH, UK Tel: +44 (0) 20 7199 1640 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7504 8283 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cmppublishing.com All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

1 the Attar Casket of Tipu Sultan1 by Sarah Longair and Cam Sharp-Jones This Intricately-Decorated Filigree Casket Is Currently

The East India Company at Home, 1757-1857 – UCL History The attar casket of Tipu Sultan1 By Sarah Longair and Cam Sharp-Jones Please note that this case study was first published on blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah in May 2013. For citation advice, visit: http://blogs.uc.ac.uk/eicah/usingthewebsite. The attar casket, 1904,1006.1.a-I, British Museum This intricately-decorated filigree casket is currently on display in the Addis Gallery of Islamic Art, located by the north entrance of the British Museum. Inside are six small bottles, a ladle and a funnel which bears a minute Persian inscription on the rim. Two documents written by one- time owners of the casket – one an undated letter; the other an incomplete note – give tantalising and fragmentary references to the casket’s provenance from the palace of Tipu Sultan (c.1750- 1799) in Seringapatam (present-day Sriringapatna).2 1 The authors would like to thank Margot Finn, Kate Smith, Helen Clifford, Richard Blurton, Ladan Akbarnia, Sarah Choy, Vesta Curtis and Paramdip Khera for their advice and assistance in researching this case study. 2http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/search_object_details.aspx?objectid=24 9650&partid=1&searchText=1904%2c1006.1.a&fromADBC=ad&toADBC=ad&numpages=10&orig=%2fresearch 1 The East India Company at Home, 1757-1857 – UCL History ---------- Document 1: At the taking of Seringapatam in 1799 my Uncle Mr Fraser was present and afterwards appointed Prize Agent to the treasures, jewels, etc there found. This silver coffer was in Tipoo's own room and with a silken carpet and coral chaplet was sent by HF to his mother at Mt Capper and were by her given to her youngest daughter Charlotte Catherine, From whom the boxe was given to her son J M Heath who wished his youngest cousin H Fraser to have it as a family relic. -

Aurangzeb Mughal Empire Continued

UPSC – IAS Civil Services Examinations Union Public Service Commission General Studies Paper I – Volume 2 Modern India & World History Index Modern India 1. Overview of Modern India 1 2. Decline of Mughals 2 3. Expansion of British Empire in India 10 • Anglo Mysore War • Anglo Maratha War • Doctrine of Lapse • Doctrine of Subsidiary Alliance • Battle of Plassey • Battle of Buxar 4. Revolt of 1857 32 5. Peasant Movements of 19th Century 45 6. Socio Religious Reforms 47 7. Indian National Congress (Early Phases) 54 8. Partition of Bengal 60 9. Era of Non Co-operation 64 • Rowlett Act • Rise of Gandhiji • Khilafat Satyagraha • Non Co-operation Movement 10. Run Up to Civil Disobedience 74 11. Quit India Movement 82 12. Some key Facts and Short notes for Pre-Exam 84 World History 1. Industrial Revolution 101 2. American Revolution 105 3. French Revolution 112 4. World War 1st 113 5. Paris Peace Settlement 1919 117 6. Rise of Nazims 120 7. World War 2nd 122 MODERN INDIA OVERVIEW Q. Revolt of 1857 marked landmark (water shed) in forming British policies in India. (2016 mains) Background ↓ Emerging circumstances ↓ Impact Analysis Modern India (1707-1947) 1. Decline of Mughal Empire (1707-1757) 2. Rise of India states (1720-1800) 3. British Ascendency in India (1757-1818) ● Events ● Economic Policies ● Political Policies 4. Socio Religious Movement in India (19th and 20th century) 5. The Revolt of 1857. 6. Beginning of India Nationalism 7. Freedom Movement.(1885-1947) 8. Misc:- ● Education policy of British. ● Famine policy of British ● Tribal peasant and castle Movement. ● Role of women in India freedom Movement and in Social Reformation. -

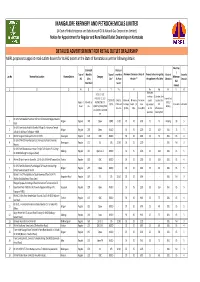

Final for Advertisement.Xlsx

MANGALORE REFINERY AND PETROCHEMICALS LIMITED (A Govt of India Enterprise and Subsidiary of Oil & Natural Gas Corporation Limited) Notice for Appointment for Regular and Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships in Karnataka DETAILED ADVERTISEMENT FOR RETAIL OUTLET DEALERSHIP MRPL proposes to appoint retail outlets dealers for its HiQ outlets in the State of Karnataka as per the following details: Fixed Fee Estimated Rent per / Type of Monthly Type of month in Minimum Dimension /Area of Finance to be arranged by Mode of Security Loc.No Name of the Location Revnue District Category Minimum RO Sales Site* Rs.P per the site ** the applicant in Rs Lakhs Selection Deposit Bid Potential # Sq.mt amount 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 7A 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Estimated SC/SC CC-1/SC working Estimated fund PH/ST/ST CC-1/ST Draw of Lots CODO/DOD Only for Minimum Minimum Minimum capital required for Regular / MS+HSD in PH/OBC/OBC CC- (DOL) / O/CFS CODO and Frontage Depth (in Area requirement RO in Rs Lakhs in Rs Lakhs Rural KLs 1/OBC PH/OPEN/OPEN Bidding CFS sites (in Mts) Mts) (in Sq.Mts) for RO infrastructure CC-1/OPEN CC-2/OPEN operation development PH On LHS From Mezban Function Hall To Indal Circle On Belgavi Bauxite 1 Belgavi Regular 240 Open CODO 51.00 20 20 600 25 15 Bidding 30 5 Road On LHS From Kerala Hotel In Biranholi Village To Hanuman Temple 2 Belgavi Regular 230 Open DODO - 35 35 1225 25 100 DOL 15 5 ,Ukkad On Kolhapur To Belgavi - NH48 3 Within Tanigere Panchayath Limit On SH 76 Davangere Regular 105 OBC DODO - 30 30 900 25 75 DOL 15 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards 4 Ramnagara Regular 171 SC CFS 22.90 35 35 1225 - - DOL Nil 3 Mysore On LHS From Sharanabasaveshwar Temple To St Xaviers P U College 5 Kalburgi Regular 225 Open CC-1 DODO - 35 35 1225 25 100 DOL 15 5 On NH50 (Kalburgi To Vijaypura Road) 6 Within 02 Kms From Km Stone No. -

Heritage of Mysore Division

HERITAGE OF MYSORE DIVISION - Mysore, Mandya, Hassan, Chickmagalur, Kodagu, Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Chamarajanagar Districts. Prepared by: Dr. J.V.Gayathri, Deputy Director, Arcaheology, Museums and Heritage Department, Palace Complex, Mysore 570 001. Phone:0821-2424671. The rule of Kadambas, the Chalukyas, Gangas, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas, Vijayanagar rulers, the Bahamanis of Gulbarga and Bidar, Adilshahis of Bijapur, Mysore Wodeyars, the Keladi rulers, Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan and the rule of British Commissioners have left behind Forts, Magnificient Palaces, Temples, Mosques, Churches and beautiful works of art and architecture in Karnataka. The fauna and flora, the National parks, the animal and bird sanctuaries provide a sight of wild animals like elephants, tigers, bisons, deers, black bucks, peacocks and many species in their natural habitat. A rich variety of flora like: aromatic sandalwood, pipal and banyan trees are abundantly available in the State. The river Cauvery, Tunga, Krishna, Kapila – enrich the soil of the land and contribute to the State’s agricultural prosperity. The water falls created by the rivers are a feast to the eyes of the outlookers. Historical bakground: Karnataka is a land with rich historical past. It has many pre-historic sites and most of them are in the river valleys. The pre-historic culture of Karnataka is quite distinct from the pre- historic culture of North India, which may be compared with that existed in Africa. 1 Parts of Karnataka were subject to the rule of the Nandas, Mauryas and the Shatavahanas; Chandragupta Maurya (either Chandragupta I or Sannati Chandragupta Asoka’s grandson) is believed to have visited Sravanabelagola and spent his last years in this place.