The Peregrine Fund 2017 Annual Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ECOLOGICAL REQUIREMENTS of the NEW ZEALAND FALCON (Falco Novaeseelandiae) in PLANTATION FORESTRY

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. THE ECOLOGICAL REQUIREMENTS OF THE NEW ZEALAND FALCON (Falco novaeseelandiae) IN PLANTATION FORESTRY A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Richard Seaton 2007 Adult female New Zealand falcon. D. Stewart 2003. “The hawks, eagles and falcons have been an inspiration to people of all races and creeds since the dawn of civilisation. We cannot afford to lose any species of the birds of prey without an effort commensurate with the inspiration of courage, integrity and nobility that they have given humanity…If we fail on this point, we fail in the basic philosophy of feeling a part of our universe and all that goes with it.” Morley Nelson, 2002. iii iv ABSTRACT Commercial pine plantations made up of exotic tree species are increasingly recognised as habitats that can contribute significantly to the conservation of indigenous biodiversity in New Zealand. Encouraging this biodiversity by employing sympathetic forestry management techniques not only offers benefits for indigenous flora and fauna but can also be economically advantageous for the forestry industry. The New Zealand falcon (Falco novaeseelandiae) or Karearea, is a threatened species, endemic to the islands of New Zealand, that has recently been discovered breeding in pine plantations. This research determines the ecological requirements of New Zealand falcons in this habitat, enabling recommendations for sympathetic forestry management to be made. -

Systematics and Conservation of the Hook-Billed Kite Including the Island Taxa from Cuba and Grenada J

Animal Conservation. Print ISSN 1367-9430 Systematics and conservation of the hook-billed kite including the island taxa from Cuba and Grenada J. A. Johnson1,2, R. Thorstrom1 & D. P. Mindell2 1 The Peregrine Fund, Boise, ID, USA 2 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, MI, USA Keywords Abstract phylogenetics; coalescence; divergence; conservation; cryptic species; Chondrohierax. Taxonomic uncertainties within the genus Chondrohierax stem from the high degree of variation in bill size and plumage coloration throughout the geographic Correspondence range of the single recognized species, hook-billed kite Chondrohierax uncinatus. Jeff A. Johnson, Department of Ecology & These uncertainties impede conservation efforts as local populations have declined Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan throughout much of its geographic range from the Neotropics in Central America Museum of Zoology, 1109 Geddes Avenue, to northern Argentina and Paraguay, including two island populations on Cuba Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA. and Grenada, and it is not known whether barriers to dispersal exist between any Email: [email protected] of these areas. Here, we present mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA; cytochrome B and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2) phylogenetic analyses of Chondrohierax, with Received 2 December 2006; accepted particular emphasis on the two island taxa (from Cuba, Chondrohierax uncinatus 20 April 2007 wilsonii and from Grenada, Chondrohierax uncinatus mirus). The mtDNA phylo- genetic results suggest that hook-billed kites on both islands are unique; however, doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2007.00118.x the Cuban kite has much greater divergence estimates (1.8–2.0% corrected sequence divergence) when compared with the mainland populations than does the Grenada hook-billed kite (0.1–0.3%). -

Shouldered Hawk and Aplomado Falcon from Quaternary Asphalt

MARCH 2003 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 71 J. RaptorRes. 37(1):71-75 ¸ 2003 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. RED-SHOULDEREDHAWK AND APLOMADO FALCON FROM QUATERNARY ASPHALT DEPOSITS IN CUBA WILLIAM SU•REZ MuseoNacional de Historia Natural, Obispo61, Plaza deArmas; La Habana CP 10100 Cuba STORRS L. OLSON • NationalMuseum of Natural History,Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 U.S.A. KEYWORDS: AplomadoFalcon; Falco femoralis;Red-shoul- MATERIAL EXAMINED deredHawk; Buteo lineatus;Antilles; Cuba; extinctions; Jbssil Fossils are from the collections of the Museo Nacional birds;Quaternary; West Indies. de Historia Natural, La Habana, Cuba (MNHNCu). Mod- ern comparativeskeletons included specimensof all of The fossil avifauna of Cuba is remarkable for its diver- the speciesof Buteoand Falcoin the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, sity of raptors,some of very large size, both diurnal and DC (USNM). The following specimenswere used tbr the nocturnal (Arredondo 1976, 1984, Su'•rez and Arredon- tables of measurements: Buteo lineatus 16633-16634, do 1997). This diversitycontinues to increase(e.g., Su'•- 17952-17953, 18798, 18846, 18848, 18965, 19108, 19929, rez and Olson 2001a, b, 2003a) and many additionalspe- 290343, 291174-291175, 291197-291200, 291216, cies are known that await description. Not all of the 291860-291861, 291883, 291886, 296343, 321580, raptors that have disappearedfrom Cuba in the Quater- 343441, 499423, 499626, 499646, 500999-501000, nary are extinct species,however. We report here the first 610743-610744, 614338; Falcofemoralis 30896, 291300, 319446, 622320-622321. recordsfor Cuba of two widespreadliving speciesthat are not known in the Antilles today. Family Accipitridae Thesefossils were obtainedduring recentpaleontolog- Genus ButeoLacepede ical exploration of an asphalt deposit, Las Breasde San Red-shouldered Hawk Buteolineatus (Gmelin) Felipe, which is so far the only "tar pit" site known in (Fig. -

The Order Falconiformes in Cuba: Status, Distribution, Migration and Conservation

Chancellor, R. D. & B.-U. Meyburg eds. 2004 Raptors Worldwide WWGBP/MME The order Falconiformes in Cuba: status, distribution, migration and conservation Freddy Rodriguez Santana INTRODUCTION Fifteen species of raptors have been reported in Cuba including residents, migrants, transients, vagrants and one endemic species, Gundlach's Hawk. As a rule, studies on the biology, ecology and migration as well as conservation and management actions of these species have yet to be carried out. Since the XVI century, the Cuban archipelago has lost its natural forests gradually to nearly 14 % of the total area in 1959 (CIGEA 2000). Today, Cuba has 20 % of its territory covered by forests (CIGEA op. cit) and one of the main objectives of the Cuban environmental laws is to protect important areas for biodiversity as well as threatened, migratory, commercial and endemic species. Nevertheless, the absence of raptor studies, poor implementation of the laws, insufficient environmental education level among Cuban citizens and the bad economic situation since the 1990s continue to threaten the population of raptors and their habitats. As a result, the endemic Gundlach's Hawk is endangered, the resident Hook-billed Kite is almost extirpated from the archipelago, and the resident race of the Sharp-shinned Hawk is also endangered. Studies on these species, as well as conservation and management plans based on sound biological data, are needed for the preservation of these and the habitats upon which they depend. I offer an overview of the status, distribution, threats, migration and conservation of Cuba's Falconiformes. MATERIALS AND METHODS For the status and distribution of the Falconiformes in Cuba, I reviewed the latest published literature available as well as my own published and unpublished data. -

Survival, Movements and Habitat Use of Aplomado Falcons Released in Southern Texas

THE JOURNAL OF RAPTOR RESEARCH A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE RAPTOR RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 30 DECEMBEg 1996 NO. 4 j. RaptorRes. 30(4):175-182 ¸ 1996 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. SURVIVAL, MOVEMENTS AND HABITAT USE OF APLOMADO FALCONS RELEASED IN SOUTHERN TEXAS CHRISTOPHERJ. PEREZ 1 New MexicoCooperative Fish and WildlifeResearch Unit, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. PHILLIPJ. ZWANK U.S. NationalBiological Service, New MexicoCooperative Fish and WildlifeResearch Unit, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. DAVID W. SMITH Departmentof ExperimentalStatistics, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. A•sTv,ACT.--Aplomado falcons (Falcofemoralis)formerly bred in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. Nest- ing in the U.S. waslast documentedin 1952. In 1986, aplomadofalcons were listed as endangeredand efforts to reestablishthem in their former range were begun by releasingcaptive-reared individuals in southern Texas. From 1993-94, 38 hatch-yearfalcons were released on Laguna AtascosaNational Wild- life Refuge.Two to 3 wk after release,28 falconswere recapturedfor attachmentof tail-mountedradio- transmitters.We report on survival,movements, and habitat use of these birds. In 1993 and 1994, four and five mortalities occurred within 2 and 4 wk of release, respectively.From 2-6 mo post-release,11 male and three female radio-taggedaplomado falcons used a home range of about 739 km• (range = 36-281 km2). Most movementsdid not extend beyond10 km from the refuge boundary,but a moni- tored male dispersed136 km north when 70 d old. Averagelinear distanceof daily movementswas 34 _+5 (SD) km. After falconshad been released75 d, they consistentlyused specific areas to forageand roost. -

Hunting with the Aplomado Falcon in the U.S

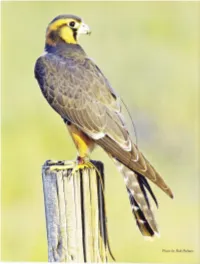

!\ \ Pltrtto bt, Rob Palmer nalDd qoa q opqd flN ouolFurrrueg 'O'IA[ ururtul senruf 's'n, oql u gWoppurold wffipn Ig 'S'n aql ut uoJIeJ opeuoldy aqt qll^{ Surlung 32 Hunting with the Aplomado falcon in the U.S prey such as bobrvhites. Aplomado Falcons are social to the extent that mated pairs hunt together and catr be found together throughout the year and they hunt cooperativeli' r,vhen chasing avian prey. Siblings remain together for some time after becoming independent and hunt together. In Hector's study, birds account for an estirnated 97% of the prey biomass. Most birds are sized witl-r the smallest .J dove to robin being a hummingbird. The most ,-.€' commonly taken birds rvere lvhitc- '* winged doves, great tailed grackles. *.. * groove billed anis and yellorv billed cuckoos. Y had heard and read about I aolomado falcons bul ner er' I to have the op- portunity"lp".,"d to fly one. When I sarl that.|im Nelson, a falconer in Ken- newick, Washington, was breeding them, I thought long and hard about obtaining one. I currentl)' fly a f'emale peregrinc on ducks, pheasants and prairie chickens in Nebraska and I recentll' lost mv I'emale barbary'x merlin to a mptor. I love the stoop but I realll,missed thc pursuit flights at snrall avian quarry/. The advantage o1'{l,ving a "; pursuit falcon is that slips :rt small at,iau quar r)1 are plentifirl through- : r :E:= out the year and it is fiil-r to rvatch. I -.:13'.:::# knerv that purchasine an aplomado rvas going to be expensivc and thel' ilttthor ancl Sgt. -

Peregrine Falcons for the Nation's Capital

DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE news release For Release June 20, 1979 Alan Levitt 202/343-5634 PEREGRINE FALCONS FOR THE NATION'S CAPITAL Four captive-bred, month-old peregrine falcons have been placed in a man-made nest atop the Department of the Interior Building in the Nation's Capital in the first attempt to restock this endangered bird of prey into a major U.S. metropolitan area, Secretary of the Interior Cecil D. Andrus announced today. "The prospects of seeking this magnificent bird once again soaring above the Nation's Capital testifies to the fact that all the news about endangered species is not gloom and doom," Andrus said, prior to piacement of the peregrines on the roof. Andrus has been a long-time supporter of the Birds of Prey Natural Area in Idaho, which contains wild peregrines. "This is a happy occasion. The peregrine release symbolizes the less publicized, but critically important work of endangered species recovery teams. These are teams of the Nation's finest biologists from the Federal, State, and private levels --who map out plans to ensure the survival of species facing extinction." Two biologists will live in the eight-story building, two blocks from the White House, for the next 6 weeks to study, feed, and assist the young falcons as they grow up and learn to fly. The human help is necessary because there are no wild peregrines to do the job. Pesticides and other toxic chemicals have wiped out all wild breeding peregrines east of the Rocky Xountains. -

Donated to the Peregrine Fund

10 December 2015 THE PEREGRINE FUND RESEARCH LIBRARY DUPLICATE BOOKS, REPORTS AND THESES All proceeds from the sale of these items are used to add new titles to our library. Every book you purchase from us results in an addition to two libraries – yours and ours! Inquiries should be sent to [email protected] or you may call (208) 362- 8253. We accept payment by credit card, money order, check in U.S. dollars, or cash in U.S. dollars. Final prices include domestic media mail shipping costs of $3 for the first item and $1 for each additional title. Shipping costs for large orders are billed at actual cost. We honor purchase orders from institutional libraries, but request advance payment from other buyers. Descriptions are based on standard terms used widely in the book trade: Mint: As new (generally in original cellophane wrapping) Fine: No defect in book or dustjacket, but not as crisp as a new book Very good: Very light wear with no large tears or major defects Good: Average used condition with some defects, as described. Fair: A “reading copy” with major defects “Wrappers” = paper covers. If this term is not included, the book is hardbound. “dj” = dustjacket (or “dustwrapper”). “ex-lib” = library copy with the usual marks Publications may be returned for any reason in the original carton for a full refund of the purchase price plus media mail shipping costs. 1 ABBOTT, R.T. 1982. Kingdom of the seashell. Bonanza Books, Crown Publishers, Inc. 256 pp. $5. ABBOTT, R. T. 1990. Seashells. American Nature Guides. -

Seasonal Diet of the Aplomado Falcon &Lpar;<I>Falco Femoralis</I>&Rpar

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS j RaptorRes. 39(1):55-60 ¸ 2005 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. SEASONALDIET OF THE APLOMADOFALCON (FALCOFEMORALIS) IN AN AGRtCULTURALARE• OF ARAUCAN•, SOUTHERN CHILE POCARDOA. FIGUEROAROJAS 1 AND EMA SOR•YACOMES STAPPUNG Estudiospara la Conservaci6ny Manejo de la Vida SilvestreConsultores, Blanco Encalada 350, Chilltin, Chile KEYWORDS: AplomadoFalcon; Falco femoralis; diet;agri- cania region, southern Chile. The landscape is com- cultural areas;,Chile. prised mainly of wheat and oat crops,scattered pasture and sedge-rush(Carex-Juncus spp.) marshes,small plan- The Aplomado Falcon (Falcofemoralis) is distributed tations of nonnativePinus spp. and Eucalyptusspp., and from southwesternUnited Statesto Tierra del Fuego Isla remnants of the native southern beech (Nothofagusspp.) forest. The climate is moist-temperatewith a Mediterra- Grande in southern Argentina and Chile. Aplomados in- nean influence (di Castriand Hajek 1976). Mean annual habit open areas such as savannas,desert grasslands,An- rainfall and temperatureare 1400 mm and 12øC,respec- dean and Patagonian steppes,and tree-lined pastures, tively. from coastalplains up to 4000 m in the Andes (Brown From August (austral winter) to December (austral and Areadon 1968, de la Pefia and Rumboll 1998). In spring-summer) 1997, we collected 65 pellets under the United States,the Aplomado Falcon is listed as en- trees and fence postsused as pluck sitesby at least one dangered (Shull 1986) due to the historical modification pair of AplomadoFalcons. We collected40 pelletsduring of its habitats and cumulative effects of DDT (Kiff et al. winter and 25 during spring-summer.A few prey remains 1980, Hector 1987). In contrast,the Chilean population were also collected beneath pluck sites during the may be increasing.Forest conversion to agricultural lands spring-summer period. -

Aplomado Falcon Abundance and Distribution in the Northern Chihuahuan Desert of Mexico

THE JOURNAL OF RAPTOR RESEARCH A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE RAPTOR RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 38 JUNF,2004 NO. 2 j Raptorlies. 38(2):107-117 ¸ 2004 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. APLOMADO FALCON ABUNDANCE AND DISTRIBUTION IN THE NORTHERN CHIHUAHUAN DESERT OF MEXICO KENDAL E. YOUNG 1 AND BRUCE C. THOMPSON 2 NewMexico Cooperative Fish and WildliJbResearch Unit and Fisheryand Wildli? SciencesDepartment, Box 30003, MSC 4901, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. ALBERTO LAF(SN TERRAZAS Facultad de Zootecnia, UniversidadAut6noma de Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico ANGEL B. MONTOYA ThePeregrine Fund, Boise,11) 83709 U.S.A. RAUL VALDEZ Fisheryand WildliJkSdences Department, Box 30003, MSC 4901, NewMexico State University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. AnSTRACT.--Thenorthern Aplomado Falcon (Falcofemoralis septentrionalis) historically occupied coastal prairies, savannas,and desert grasslandsfrom southern Mexico north to southern and southwestern Texas,southern New Mexico, and southeasternArizona. Current residentAplomado Falconpopulations are primarily in Mexico, with isolatedpopulations in southernTexas and from northern Chihuahuato southern New Mexico. We conductedsurveys in semidesertgrasslands/savannas and associatedhabitats in northern Chihuahua to locate Aplomado Falconsand to better delineate their distribution and abundancein the northern Chihuahuan Desert during 1998-99. Data were collectedby surveyinglarge tracts,transects in nonrandomlyselected grasslands, and from a falcon monitoring study.Based on all surveyeffort, the minimum knownpopulation of adult Aplomado Falconsin the studyarea in northern Chihuahua was79 individuals.Aplomado Falconswere primarily associatedwith grasslandcommunities. Most falcon nests (88%) were found in grasslandcommunities with soaptreeyucca (Yuccaelata) or Torrey yucca (Y. torreyi).Aplomado Falconswere found fairly clusteredin the north-centralto north- eastern part of the study area. -

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 Migratory Bird Program Table of Contents

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 Migratory Bird Program Table Of Contents Executive Summary 4 Acknowledgments 5 Introduction 6 Methods 7 Geographic Scope 7 Birds Considered 7 Assessing Conservation Status 7 Identifying Birds of Conservation Concern 10 Results and Discussion 11 Literature Cited 13 Figures 15 Figure 1. Map of terrestrial Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs) Marine Bird Conservation Regions (MBCRs) of North America (Bird Studies Canada and NABCI 2014). See Table 2 for BCR and MBCR names. 15 Tables 16 Table 1. Island states, commonwealths, territories and other affiliations of the United States (USA), including the USA territorial sea, contiguous zone and exclusive economic zone considered in the development of the Birds of Conservation Concern 2021. 16 Table 2. Terrestrial Bird Conservation Regions (BCR) and Marine Bird Conservation Regions (MBCR) either wholly or partially within the jurisdiction of the Continental USA, including Alaska, used in the Birds of Conservation Concern 2021. 17 Table 3. Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 in the Continental USA (CON), continental Bird Conservation Regions (BCR), Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands (PRVI), and Hawaii and Pacific Islands (HAPI). Refer to Appendix 1 for scientific names of species, subspecies and populations Breeding (X) and nonbreeding (nb) status are indicated for each geography. Parenthesized names indicate conservation concern only exists for a specific subspecies or population. 18 Table 4. Numbers of taxa of Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 represented on the Continental USA (CON), continental Bird Conservation Region (BCR), Puerto Rico and VirginIslands (PRVI), Hawaii and Pacific Islands (HAPI) lists by general taxonomic groups. Also presented are the unique taxa represented on all lists.